U.S. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright had the opportunity to see first-hand how Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory drives American leadership in particle physics and leverages the lab’s unique capabilities to unleash American innovation and discovery, during his recent visit.

Secretary Wright viewed Fermilab’s Main Injector, one of the laboratory’s five particle accelerators and a contributor to some of Fermilab’s groundbreaking discoveries. The Main Injector is notable for producing the world’s most powerful high-energy neutrino beam.

He also had the opportunity to view Fermilab’s key flagship projects intended to define the future of particle physics and sustain U.S. scientific preeminence for decades to come. This included a visit to Fermilab’s underground laboratory to see a prototype detector for the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility-Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (LBNF-DUNE) project, which will use neutrinos to probe the Standard Model of particle physics and increase our understanding of why our universe is dominated by matter. LBNF-DUNE’s near detectors in Illinois will use artificial intelligence tools to analyze neutrino events in liquid argon detectors and classify different particle types.

In addition, Secretary Wright saw work underway on the Proton Improvement Plan-II (PIP-II), which will generate an unprecedented stream of neutrinos for LBNF-DUNE and provide powerful proton beams to other experiments. To mark his visit, Wright signed one of the PIP-II cryomodules, a crucial component of the accelerator that will send a beam of neutrinos 800 miles though the Earth to the LBNF-DUNE far detectors in Lead, South Dakota.

Secretary Wright’s visit also included a tour of Fermilab’s Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center (SQMS), a collaboration of 36 partner institutions composed of national labs, academia and industry. At SQMS, one of DOE’s five National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, Secretary Wright learned more about Fermilab’s support for developing and deploying quantum computers, and the unprecedented computational opportunities and impacts they will have in science and society.

Secretary Wright then saw the important work being done by the Applied Physics and Superconducting Technology Division (APST-D) at the lab, where researchers are pursuing a highly innovative development program in cryogenics, superconducting magnets and superconducting radio frequency cavities, all crucial for next-generation particle accelerators and quantum research. Among its many projects, APST-D is constructing superconducting magnets for the high-luminosity upgrade to the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN.

Inside Fermilab’s iconic Wilson Hall, the Secretary viewed the Remote Operations Center for the CMS experiment at CERN. CMS is one of two particle detectors at the Large Hadron Collider that confirmed the existence of the Higgs boson, and Fermilab is the host institution for the U.S. collaboration that contributed to the historic discovery.

At the conclusion of his visit, Secretary Wright addressed a packed auditorium.

“We have to drive energy technology forward.” Wright said. “Nuclear is incredibly promising. Fusion — I believe with the help of AI, with the help of brilliant scientists like in this room — I believe we’re going to have multiple pathways to harness fusion energy.”

“We have national labs that work in applied science, engineering … Just as important, and maybe even more inspiring to me is the basic science that is done in our labs,” Wright added. “The leader of the pack is right here at Fermi, where a huge amount of the effort is just trying to understand the basic structure of the cosmos.”

Secretary Wright’s visit marked his 10th stop in his goal to visit all 17 of the U.S. Department of Energy’s national laboratories this year. His visit coincided with this year’s annual Fermilab Users and Affiliates meeting, which brings together hundreds of researchers in the broad Fermilab community and illustrates how Fermilab leads collaborative efforts across U.S. national labs and international research institutions to better solve today’s most complex scientific challenges.

“It was an honor to have Secretary Wright visit Fermilab to see how we serve today as the neutrino capital of the world to advance scientific innovation, and our work underway to ensure Fermilab contributes to groundbreaking discoveries into the future,” Fermilab Interim Director Young-Kee Kim said. “Secretary Wright deeply appreciates the benefits of basic scientific research, and the role of laboratories like Fermilab in America’s future. Most importantly, his visit provided him the opportunity to meet and engage with the men and women of the Fermilab community — the key to our scientific success.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

Twenty-five years ago, there was a hole in the Standard Model. And on July 21, 2000, an experiment called DONUT filled it.

That’s when a team of 54 physicists from the United States, Japan, South Korea and Greece announced the first-ever detection of the tau neutrino, one of the last unseen particles in the Standard Model of particle physics. They were part of the Direct Observation of the Nu Tau, or DONUT, collaboration based at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

“We knew there was a tau neutrino — there had to be,” said Regina Rameika, a member of DONUT at the time and now associate director for high-energy physics at the Department of Energy. “But the fact is, we never had observed the signature of the interaction.”

Neutrinos are incredibly lightweight subatomic particles that were first postulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1930. In 1956, physicists saw the first neutrino at the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina. They didn’t know about the neutrino’s different types, or flavors, at the time, but this first neutrino turned out to be an electron neutrino. In 1962, physicists at Brookhaven National Laboratory detected the second type, the muon neutrino.

The idea of a third flavor of neutrino materialized after an experiment led by physicist Martin Perl at SLAC National Laboratory found a particle called the tau in 1975. The tau is the third generation of particles known as leptons. Since the other two leptons — electrons and muons — had corresponding neutrinos, it made sense that there must also be neutrinos corresponding to the tau. Sure enough, experiments found indirect evidence for the tau neutrino’s existence.

But direct observational evidence remained scarce. Until DONUT.

Making DONUT

In the early 1990s, Fermilab physicists were gearing up for the Neutrinos at the Main Injector project, or NuMI, to search for neutrino mass. As the story goes, Fermilab scientists Rameika and Byron Lundberg were discussing how excited they were for NuMI and realized it would be very useful to directly observe the tau neutrino first. The idea for the DONUT experiment was born.

Lundberg and Rameika reunited a group of scientists who had worked on Fermilab’s Experiment 653 in the mid-1980s. E653 incorporated emulsion plates developed by physicists at Nagoya University in Japan to look for charm particles. DONUT would use similar technology to search for evidence of tau neutrinos.

The DONUT collaboration submitted their proposal in 1994 and were taking data by 1997.

“By today’s standards, it was actually relatively simple,” said Rameika. “Combined, it was difficult.”

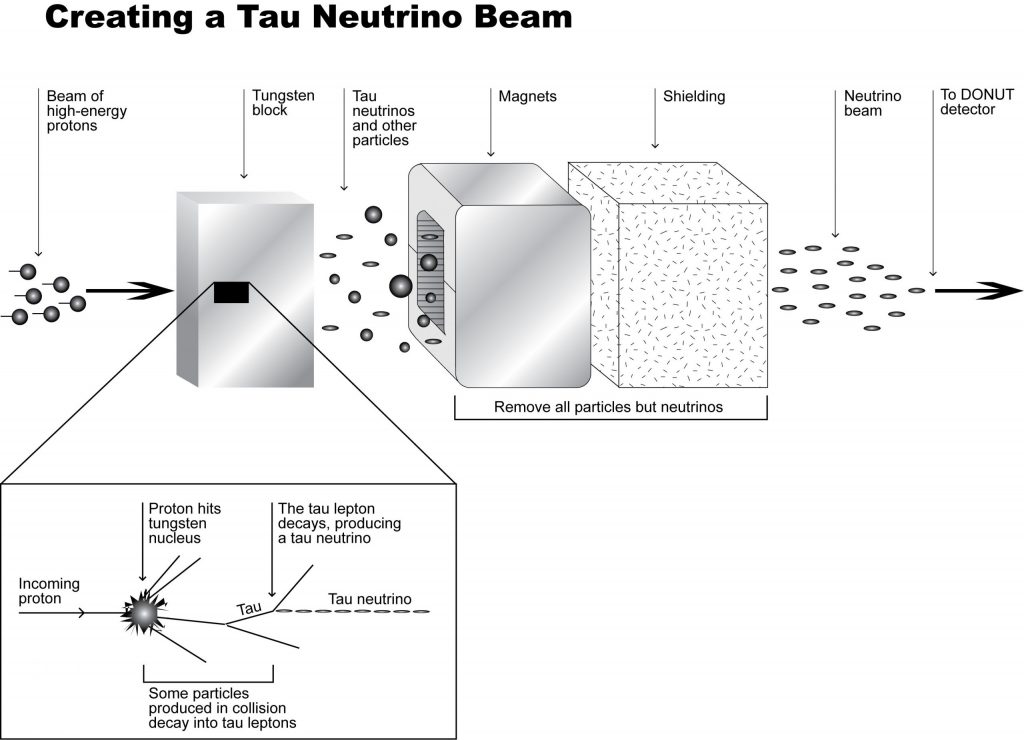

One challenge for DONUT was shoehorning it into the existing Fermilab program. The lab was uniquely equipped for this experiment because the Tevatron’s 800-GeV proton beam was essential for achieving the flux and energies they required to have even a chance of detecting tau neutrinos. But other experiments needed the beam, too. To make the effort as easy as possible for the lab, the collaboration repurposed existing equipment.

The experiment consisted of a 3-foot-long structure made of iron plates sandwiched with plates of emulsion. When Fermilab’s Tevatron accelerator shot a beam of particles at this target, the neutrinos interacted with the iron nuclei. The resulting particles shot through the emulsion plates, leaving tracks behind like animal footprints in the snow.

But if the experimenters weren’t careful, the emulsion plates could get polluted. The Tevatron beam produced an enormous amount of muons in addition to neutrinos, and these muons would overexpose the emulsion plates. Fortunately, since muons are charged particles, they can be steered with magnets, which don’t affect neutrinos.

Vittorio Paolone, who was co-spokesperson for DONUT with Lundberg at the time, compared the muon challenge to being between the jaws of a lion. “You have the jaws open, and then you have to stick the emulsion in between and hope it doesn’t clamp down at some point,” he said.

If the metaphorical jaws did clamp down, muons would flood the emulsion plates and DONUT would lose all their data. It would be akin to exposing a roll of film to the light before developing the photos. There were safeguards in place to protect the data: if the sweeping magnets failed, the beamline would automatically shut off. Fortunately for DONUT — and for every other Fermilab experiment using the beam at the same time — the magnet held steady.

With Fermilab’s high-energy proton beam, the nuclear emulsion technology pioneered by Nagoya University and the sweeping magnet system that shielded the detector, DONUT was the product of scientific serendipity. “The detection of tau-neutrino interactions using particle accelerators was only possible because three unique capabilities could be employed in a synergistic manner at the time DONUT was proposed,” said Lundberg.

After collecting data from 1997 to 1998, collaborators in Nagoya worked on digitizing and analyzing the emulsion plates. They then sent the data back to Fermilab for further analysis, which included early forms of machine learning and artificial intelligence. “We were one of the first experiments using neural networks,” said Rameika.

In total, DONUT collected 6.6 million particle interactions, which they narrowed down to about 1,000 candidate events.

If tau neutrinos acted as predicted, physicists expected to see their tell-tale signature in the emulsion plates: a short track with a kink in it, indicating a tau neutrino had hit an iron nucleus and produced a tau lepton, which traveled for about a millimeter before decaying.

“The signature is pretty obvious,” said Paolone, now a professor at the University of Pittsburgh. “Even though it looks exactly the way you expect it to look, when you start seeing three or four that look like a tau neutrino interaction … you start to get pretty excited.”

On July 21, 2000, Lundberg announced the detections of four tau neutrino interactions to a packed lecture hall at Fermilab. They had finally seen the penultimate piece of the Standard Model. (The observation of the final piece, the Higgs boson, would be announced 12 years later.) Ultimately, DONUT found a total of nine tau neutrino interactions.

“Personally, commissioning and running DONUT was challenging and exhausting,” said Lundberg. “I never worked as intensely after the experiment — I doubt that I even could have.”

The long legacy of a short interaction

The hard work of a small, international group of physicists had a profound impact on the field. In 2022, the American Physical Society recognized the achievements of DONUT by awarding the W.K.H. Panofsky Prize in Experimental Particle Physics to Lundberg, Rameika, Paolone and their Nagoya University collaborator Kimio Niwa “for the first direct observation of the tau neutrino through its charged-current interactions in an emulsion detector.”

The emulsion detection technology originated at DONUT has since been used in many more experiments, including ScanPyramids, an international project using noninvasive techniques to look for hidden chambers inside the pyramids in Egypt. CERN neutrino experiments like DsTau, FASERν and SND@LHC also utilize this tech. “The origin of the current nuclear emulsion technology is in the DONUT experiment,” said Mitsuhiro Nakamura, a DONUT collaborator from Nagoya University who recently retired from physics to become a rice farmer.

Nuclear emulsion plates were also used in the OPERA experiment at the Gran Sasso Laboratory of the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics. Between 2010 and 2015, OPERA saw 10 beam-produced muon neutrinos oscillate into tau neutrinos, making it one of two experiments that has detected tau neutrinos since their first observation. The other is the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, which announced seven tau neutrino candidates from cosmic sources in 2024 and a few more in following analyses. Collectively, physicists have seen, on average, one tau neutrino per year in the last quarter century.

“It’s impressive that we don’t have larger samples,” said Paolone. “It’s an amazingly difficult particle to detect.”

Many current and future experiments are focused on detecting — or have a chance of seeing — tau neutrinos. In addition to the CERN emulsion-based detectors that will look at energies similar to and higher than to DONUT, there are large-scale water- and ice-based detectors like KM3NeT, P-ONE and an expansion to IceCube that will probe high-energy neutrinos, and proposed tau-neutrino telescopes will explore ultra-high-energy ranges.

Physicists are also continuously brainstorming new ways to study tau neutrinos. “Ever since DONUT, we’ve had to learn how to find the tau neutrino signature without actually seeing the track,” said Rameika.

Some new-generation neutrino experiments, such as the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment hosted by Fermilab, are focusing on the other two neutrino flavors that are relatively easier to detect.

Still, DONUT’s direct detection of the tau neutrino was a vital step in understanding the nature of the elusive particle.

“In order to understand neutrinos, you want to look at every channel that you possibly can,” said Rameika. “Knowing how to detect tau neutrinos, as we did with DONUT, is an important piece of information that we keep in the back of our heads for going forward and figuring out how to adapt it. In my mind, it was a critical historical experiment”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.