The construction of the Mu2e experiment at the Department of Energy’s Fermilab has reached an important milestone. A crucial section of magnets for the experiment, including components from Italy, Japan and the United States, has passed the rigorous testing necessary to ensure that each individual magnet meets the performance required for the experiment.

Those magnets, part of a section called the transport solenoid, will be pieced together to form a novel part of the Mu2e project. The Mu2e project has reached 80% completion overall, according to Mu2e Project Manager Ron Ray.

When operational, the Mu2e experiment will reach 10,000 times the sensitivity of previous experiments looking for the direct conversion of a muon into an electron to test one of the fundamental symmetries in particle physics.

Recently, the Mu2e experiment received and tested the seven superconducting units, shown here, that form the first portion of the transport solenoid. Rigorous testing of the individual units, which were manufactured in industry, ensures they meet the performance required for the experiment. Photo: Vito Lombardo, Fermilab

Why muons?

Muons may be the key to unraveling a confounding mystery in particle physics. The mystery stems from the Standard Model, or, more accurately, the holes within the Standard Model.

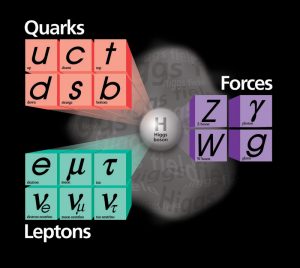

In the latter half of the 20th century, scientists developed what has become known as the Standard Model of physics. The model relates three of the four fundamental forces – the electromagnetic, the weak and the strong force – to each other. It also classifies all known elementary particles.

In the Standard Model of particle physics, the muon is in a family of particles called leptons (upper row of the green grid on lower left). Each lepton has a partner particle called a neutrino (bottom row of green grid). Unlike their partners, neutrinos lack electric charge. Scientists have observed neutrinos morphing between their three types, and they have reason to believe that the charged leptons might do the same. Image: Fermilab

But from the beginning, the Standard Model has left certain phenomena unexplained. It doesn’t include the universe’s fourth force, gravity, nor does it address the accelerating expansion of the universe due to dark energy or the existence of dark matter.

So where do muons come in?

In the Standard Model, the muon, along with the electron and tau, are in a family of particles called leptons. Each lepton has a partner particle called a neutrino: the muon neutrino, electron neutrino and tau neutrino. Unlike their partners, neutrinos lack electric charge. Scientists have observed neutrinos morphing between their three types, and they have reason to believe that the charged leptons might do the same. All they need is the right kind of experiment to find out.

The right kind of experiment

That’s where Mu2e comes in.

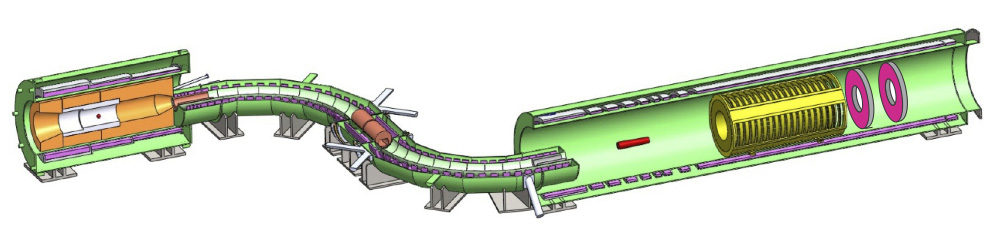

The experiment is about one-third the length of a football field and will be 10,000 times more precise when it comes to looking for this muon-to-electron conversion than a similar, previous experiment called SINDRUM II. One of the key differences from previous experiments is Mu2e’s system of three superconducting magnet systems: the production solenoid, the transport solenoid and the detector solenoid.

The production solenoid is where the muons are created. A beam of protons hits a target, and the interaction eventually produces muons. With the help of magnets, these muons then spiral down the S-shaped transport solenoid.

The transport solenoid, a critical part of the experimental setup, is divided into two halves. Muons travel down the first half of the curvy corridor, where they are separated by charge. At the solenoid’s midway point, they encounter a special device that permits only negatively charged muons to pass through to the second curved section. The negative muons then exit the transport solenoid and enter the next big magnet, the detector solenoid. There, they stop in a second target.

It’s at this point that the magic happens — the magic of quantum mechanics.

The S-shaped Mu2e transport solenoid is divided into two halves. Muons travel down the first half of the curvy corridor, where they are separated by charge. At the solenoid’s midway point, they encounter a special device that permits only negatively charged muons to pass through to the second curved section. The negative muons then exit the transport solenoid and enter the next big magnet, the detector solenoid (the larger cylinder on the right). There, they stop in a second target. Image: Mu2e

When a negative muon hits a target, only one of two things can happen according to the Standard Model: Either the muon is captured by the nucleus, changing a proton into a neutron and leaving behind a neutrino, or the muon decays, emitting an electron and two neutrinos.

But Mu2e is looking for a third option: The transformation of a muon into only an electron, unaccompanied by the usual neutrino partners. The observation of this process would break the Standard Model wide open, demonstrating that one charged lepton can convert directly into another — a theorized process no one has ever witnessed.

“What we do at Fermilab is pure research, and we’re trying to enrich the human experience by helping people understand the universe and the world we live in,” Ray said. “And ultimately what this is all about is trying to complete the picture of the Standard Model by filling in some holes that we know exist.”

Construction of the transport solenoid

Making that all happen is even more difficult than it sounds, and the transport solenoid is an important part of the design of the experiment, enabling it to be sensitive enough to observe this rare phenomenon, if it exists. The transport solenoid was first proposed decades ago to address the limitations of previous muon-to-electron conversion experiments. Fermilab is the first to fully bring this novel idea to fruition.

But first all the parts need to come together.

Recently, Mu2e received and tested the seven superconducting units that form the first portion of the transport solenoid. Rigorous testing of the individual units, which were manufactured in industry, ensures they meet the performance required for the experiment.

“For this project, we are collaborating with industries scattered all over the world,” said Vito Lombardo, Mu2e manager for the transport solenoids. “The superconducting cables, the building blocks of these magnets, came from Japan, the superconducting units that form the S-shaped magnets are being manufactured in Italy and tested at Fermilab, while the cryostats and thermal shields, the devices that help keeping the magnets cold, are coming from the United States.”

Fermilab is coordinating this global partnership.

If the planning required for the experiment wasn’t complicated enough, the S-shape of the solenoid makes it more so: Each magnet unit is unique. This means that the magnets not only have to be assembled in a specific order but that the experiment cannot rely on spares.

“They’re a very funny shape,” explained Karie Badgley, one of the scientists working on Mu2e. “You can’t just order them as you might with other magnets, especially with the tight tolerances we require.”

The rigorous testing that Fermilab puts each of these magnets through takes about four months.

“It’s been a lot of big, important steps,” Badgley said. “That’s why it’s so exciting that this first half is almost done. We can finally start to put it together and see the whole magnet-aspect of the upstream section come together.”

With the seven magnets making up the first half of the transport solenoid accepted, the team is already putting the section together. Meanwhile, testing on the magnets for the second section kicks off.

Construction of Mu2e is expected to finish in 2023, and the experiment will be ready to start taking physics data shortly after.

The Mu2e experiment at Fermilab is supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

This is a version of an article originally published on Oct. 13 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

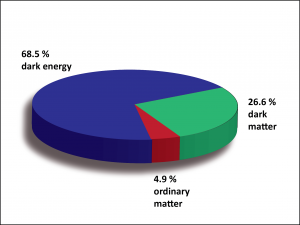

Visible matter makes up only a tiny amount of the composition of the universe. Dark energy, a mysterious entity that is accelerating the expansion of the universe, dominates, followed by dark matter, invisible material that exerts a gravitational tug.

Image: NIST

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST, and their colleagues, including Fermilab scientists Dan Carney and Gordan Krnjaic, have proposed a novel method for finding dark matter, the cosmos’s mystery material that has eluded detection for decades. Dark matter makes up about 27% of the universe; ordinary matter, such as the stuff that builds stars and planets, accounts for just 5% of the cosmos. (A mysterious entity called dark energy, accounts for the other 68%.)

According to cosmologists, all the visible material in the universe is merely floating in a vast sea of dark matter — particles that are invisible but nonetheless have mass and exert a gravitational force. Dark matter’s gravity would provide the missing glue that keeps galaxies from falling apart and account for how matter clumped together to form the universe’s rich galactic tapestry.

The proposed experiment, in which a billion millimeter-sized pendulums would act as dark matter sensors, would be the first to hunt for dark matter solely through its gravitational interaction with visible matter. The experiment would be one of the few to search for dark matter particles with a mass as great as that of a grain of salt, a scale rarely explored and never studied by sensors capable of recording tiny gravitational forces.

Previous experiments have sought dark matter by looking for nongravitational signs of interactions between the invisible particles and certain kinds of ordinary matter. That’s been the case for searches for a hypothetical type of dark matter called the WIMP (weakly interacting massive particles), which was a leading candidate for the unseen material for more than two decades. Physicists looked for evidence that when WIMPs occasionally collide with chemical substances in a detector, they emit light or kick out electric charge.

Researchers hunting for WIMPs in this way have either come up empty-handed or garnered inconclusive results; the particles are too light (theorized to range in mass between that of an electron and a proton) to detect through their gravitational tug.

Dark matter, the hidden stuff of our universe, is notoriously difficult to detect. In search of direct evidence, NIST researchers and colleagues have proposed using a 3-D array of pendulums as force detectors, which could detect the gravitational influence of passing dark matter particles. When a dark matter particle is near a suspended pendulum, the pendulum should deflect slightly due to the attraction of both masses. However, this force is very small, and difficult to isolate from environmental noise that causes the pendulum to move. To better isolate the deflections from passing particles, NIST researchers propose using a pendulum array. Environmental noise affects each pendulum individually, causing them to move independently. However, particles passing through the array will produce correlated deflections of the pendulums. Because these movements are correlated, they can be isolated from the background noise, revealing how much force a particle delivers to each pendulum and the particle’s speed and direction, or velocity. Credit: Sean Kelley/NIST

With the search for WIMPs seemingly on its last legs, researchers at NIST and their colleagues are now considering a more direct method to look for dark matter particles that have a heftier mass and therefore wield a gravitational force large enough to be detected.

“Our proposal relies purely on the gravitational coupling, the only coupling we know for sure that exists between dark matter and ordinary luminous matter,” said study co-author Daniel Carney, a theoretical physicist jointly affiliated with NIST, the Joint Quantum Institute and the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science at the University of Maryland in College Park, and the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

The researchers, who also include Jacob Taylor of NIST, JQI and QuICS; Sohitri Ghosh of JQI and QuICS; and Gordan Krnjaic of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, calculate that their method can search for dark matter particles with a minimum mass about half that of a grain of salt, or about a billion billion times the mass of a proton. The scientists reported their findings in Physical Review D.

Because the only unknown in the experiment is the mass of the dark matter particle, not how it couples to ordinary matter, “if someone builds the experiment we suggest, they either find dark matter or rule out all dark matter candidates over a wide range of possible masses,” Carney said.

The experiment would be sensitive to particles ranging from about 1/5,000 of a milligram to a few milligrams.

That mass scale is particularly interesting because it covers the so-called Planck mass, a quantity of mass determined solely by three fundamental constants of nature and equivalent to about 1/5,000 of a gram.

Carney, Taylor, Krnjaic and their colleagues propose two schemes for their gravitational dark matter experiment. Both involve tiny, millimeter-size mechanical devices acting as exquisitely sensitive gravitational detectors. The sensors would be cooled to temperatures just above absolute zero to minimize heat-related electrical noise and shielded from cosmic rays and other sources of radioactivity. In one scenario, a myriad of highly sensitive pendulums would each deflect slightly in response to the tug of a passing dark matter particle.

Similar devices (with much larger dimensions) have already been employed in the recent Nobel-Prize-winning detection of gravitational waves, ripples in the fabric of space-time predicted by Einstein’s theory of gravity. Carefully suspended mirrors, which act like pendulums, move less than the length of an atom in response to a passing gravitational wave.

In another strategy, the researchers propose using spheres levitated by a magnetic field or beads levitated by laser light. In this scheme, the levitation is switched off as the experiment begins, so that the spheres or beads are in free fall. The gravity of a passing dark matter particle would ever so slightly disturb the path of the free-falling objects.

“We are using the motion of objects as our signal,” said Taylor. “This is different from essentially every particle physics detector out there.”

The researchers calculate that an array of about a billion tiny mechanical sensors distributed over a cubic meter is required to differentiate a true dark matter particle from an ordinary particle or spurious random electrical signals or “noise” triggering a false alarm in the sensors. Ordinary subatomic particles such as neutrons (interacting through a nongravitational force) would stop dead in a single detector. In contrast, scientists expect a dark matter particle, whizzing past the array like a miniature asteroid, would gravitationally jiggle every detector in its path, one after the other.

Noise would cause individual detectors to move randomly and independently rather than sequentially, as a dark matter particle would. As a bonus, the coordinated motion of the billion detectors would reveal the direction the dark matter particle was headed as it zoomed through the array.

To fabricate so many tiny sensors, the team suggests that researchers may want to borrow techniques that the smartphone and automotive industries already use to produce large numbers of mechanical detectors.

Thanks to the sensitivity of the individual detectors, researchers employing the technology needn’t confine themselves to the dark side. A smaller-scale version of the same experiment could detect the weak forces from distant seismic waves as well as that from the passage of ordinary subatomic particles, such as neutrinos and single, low-energy photons (particles of light).

The smaller-scale experiment could even hunt for dark matter particles — if they impart a large enough kick to the detectors through a nongravitational force, as some models predict, Carney said.

“We are setting the ambitious target of building a gravitational dark matter detector, but the R&D needed to achieve that would open the door for many other detection and metrology measurements,” Carney said.

Researchers at other institutions have already begun conducting preliminary experiments using the NIST team’s blueprint.

Fermilab is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science.

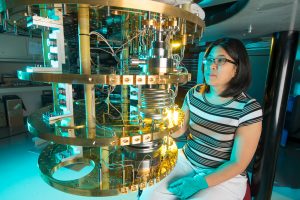

Scientist Aaron Chou, the Fermilab lead for the Quantum Science Center at Oak Ridge, will draw on his experience in dark matter detection to help test and operate topological qubits, which are expected to revolutionize the field of quantum computing. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

In August, the U.S. Department of Energy announced the establishment of five National Quantum Information Science Research Centers. Fermilab is the lead laboratory for one of them, the Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center, which joins together 20 institutions to bring about revolutionary advances in quantum computing and sensing with the goal of building and deploying a beyond-state-of-the-art quantum computer.

In a separate effort, Fermilab also plays a key role in another center — Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Quantum Science Center, or QSC.

QSC unites Oak Ridge’s powerhouse capabilities in supercomputing and materials science with Fermilab’s world-class high-energy physics instrumentation and measurement expertise and facilities.

Drawing on their experience building and operating experiments in cosmology and particle physics and in quantum information science, the Fermilab team is engaging in QSC efforts to develop novel, advanced quantum technologies.

“One of our forward-looking goals is to develop a fundamentally new kind of qubit that, if successful, could lead to next-generation quantum computers with vastly improved capabilities,” said Aaron Chou, the Fermilab lead scientist for QSC.

Those “topological” qubits would store information as imperturbable knots, making them practically immune to error. QSC combines supercomputing facilities, topological-materials science, and particle detector expertise and facilities to develop this “knotty” qubit.

Fermilab’s role in QSC advances research in three key areas.

Bringing down the noise

The first is in the design of qubits, devices that hold one quantum bit of information. Using Fermilab’s facilities built for dark matter experiments, Quantum Science Center researchers will test and operate topological qubits and novel quantum materials developed by QSC partners.

Like dark matter detectors, qubits must be able to pick up and manipulate low-level signals, which is best accomplished in an isolated location shielded from outside radioactivity and cosmic rays. Fermilab’s underground facilities for dark matter detection, 100 meters beneath Earth’s surface, provide a convenient heavily shielded spot for carrying out qubit research.

Fermilab scientist and QSC collaborator Lauren Hsu works on a dilution refrigerator to be used for a dark matter experiment. Fermilab draws on over 30 years of experience designing and operating dark matter detectors to test qubits. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

“High-energy physicists bring to the table our decades of experience in developing extremely low-threshold detectors, operated in ultralow-background environments, for dark matter searches. It turns out these are the exact same capabilities that quantum sensors are now exploring,” said Fermilab scientist Lauren Hsu, one of the QSC collaborators. “It’s a good example of how technologies developed for one specialty can advance another.”

Working to realize the vision of a future topological quantum computer is just one part of the QSC program. Just as dark matter detector research will aid in qubit advances, advances in qubits could also be a boon to dark matter research. Advanced qubit-based sensors could help look for dark matter particles in mass ranges that are currently unexplored because of the limitations of today’s detector technology.

“Bringing together experts in particle physics, materials science and computing, the center will exploit synergies between fields to potentially enable a breakthrough in dark matter searches and simultaneously make much better qubits,” Hsu said.

QSC scientists will leverage Fermilab’s underground areas — originally developed as part of the lab’s neutrino research program — to test topological qubits’ responses to faint signals and explore various exotic quantum materials for making the qubits.

“High-energy physicists bring to the table our decades of experience in developing extremely low-threshold detectors for dark matter searches. It turns out these are the exact same capabilities that quantum sensors are now exploring.” — Lauren Hsu

Examining exotic materials

Quantum-computer architects ask a great deal of their qubits. Whereas classical semiconductor computers store information using large numbers of electrons, future quantum computers must be able to control and read out information stored in single quantum excitations.

Scientists expect that such ultraprecise control can be achieved with a topological qubit. One of the first steps in its development is identifying the quantum materials that can be used to make it.

To that end, QSC collaborators are exploring a number of exotic materials, synthesizing different combinations to come up with the best formula for fabricating this next-generation device. It’s a high-volume enterprise requiring rapid cycling through large numbers of materials prototypes, each engineered a little differently from the next.

“We’re working on something that is worthy of the DOE national labs, taking on problems that are sufficiently challenging and that could not be done easily without the infrastructure and expertise of the national lab system.” — Aaron Chou

High-volume sensor work is a familiar activity at Fermilab. Over the last 10 years, Fermilab scientists have developed a strong capability for operating and reading out large amounts of data from camera sensors, such as those for the South Pole Telescope, whose camera requires the readout of 16,000-pixel sensors. As part of QSC, they are extending the capability to read out large arrays of qubits and qubit-based sensors, helping quickly ascertain which designer materials work and which don’t.

“It’s like making up a recipe for bread as you go along. You can try to change it a little bit every week. And eventually you’ll get to the point that you like what you have,” Chou said. “With 100 ovens, you can bake 100 loaves at the same time and check it all on the same day.”

The expeditious development of new quantum materials will not only bring scientists to a next-generation quantum computer that much sooner, it will also provide new quantum sensing capabilities for high-energy physics detector applications.

Extreme electronics

To simulate the performance of these exotic materials, QSC scientists will use a quantum simulator based on a technology called an “ion trap.” Unlike a quantum computer, which controls information, a quantum simulator lets information encoded in a physical system evolve naturally to better understand what happens in the real world.

Farah Fahim works on cryogenic electronics quantum computing. Designing cryogenic electronics — processors and sensors that can work at temperatures near absolute zero — is a fundamental challenge in the field of quantum computing. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

“You need a quantum computer to simulate the quantum materials needed for a quantum computer, but of course we don’t have a quantum computer. So we’re breaking this chicken-egg problem with a quantum simulator,” said Fermilab engineer Farah Fahim, QSC collaborator and deputy head of the Fermilab Quantum Science Program.

For precision operation, the ion trap must operate at the same extraordinary temperatures called for by a quantum computer — 4 kelvins and below. That means its control electronics must also be ultracold-proof.

One group of Fermilab engineers is dedicating to designing electronics that run under extreme conditions, such as those in the high-radiation environment of a particle detector. As part of QSC, they are now developing integrated circuits that can operate in near-absolute-zero temperatures. With robust electronics that can endure the biting cold, researchers will be able to scale up the computing power of an iron trap to the level needed for simulating futuristic, quantum-age materials.

“Our goal is for these electronics to be ultrafast while maintaining ultralow noise to enable excellent performance for a scalable future quantum computer,” Fahim said.

Benefits from the simulation program will redound to particle physics, too, enabling better simulations of the dynamics of quarks and nuclei.

“We’re working on something that is worthy of the DOE national labs, taking on problems that are sufficiently challenging that they probably could not be done, or at least could not be done easily, without the infrastructure and expertise of the national lab system,” Chou said.

Other partners in the Quantum Science Center are Caltech, Harvard University, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Princeton University, Purdue University, University of California, Berkeley, University of California, Santa Barbara, University of Maryland, University of Tennessee, University of Washington and industrial partners Microsoft, IBM and ColdQuanta.

“Our goal is for these electronics to be ultrafast while maintaining ultralow noise to enable excellent performance for a scalable future quantum computer.” — Farah Fahim

Learn more about quantum science at Fermilab.

Fermilab research in detector and sensor technology and in electronics engineering is supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

The NOvA experiment, best known for its measurements of neutrino oscillations using particle beams from Fermilab accelerators, has been turning its eyes to the skies, examining phenomena ranging from supernovae to magnetic monopoles. Thanks in large part to modern computing capabilities, researchers can collect and analyze data for these topics simultaneously, as well as for the primary neutrino program at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab, where it is based.

The most dramatic astrophysical phenomena that NOvA studies are supernovae. When a massive star collapses, it releases 99% of its energy in a burst of neutrinos. The other 1% becomes a visible supernova, bright enough to outshine an entire galaxy. While the neutrinos carry vastly more energy than do the particles of light, called photons, the elusive neutrinos are much more difficult to observe. Hundreds of visible-light supernovae are discovered each year, but only one since the dawn of the age of neutrino detectors has been near enough to have been seen through its neutrino signature: SN 1987A, in a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way.

The NOvA far detector — one of two particle detectors used in the NOvA experiment — is located in northern Minnesota. If a supernova were born in our galaxy, the 14,000-ton instrument would see thousands of neutrinos in a few seconds. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

Both of NOvA’s particle detectors — the near detector at Fermilab and the far detector in northern Minnesota — are capable of detecting neutrinos generated by supernovae. Each supernova-neutrino signature would appear much smaller than that from an accelerator-generated neutrino beam, but it would still be observable. If a supernova were to be born in our galaxy, NOvA’s 14,000-ton far detector would see thousands of these neutrinos in a few-second burst, and the 300-ton near detector dozens.

In a new paper to be published in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, the NOvA collaboration describes the system that will be used to trigger on such a burst. Because of the rarity of nearby supernovae and the high value of the neutrino data, NOvA uses several redundant systems to ensure the collection of supernova data. Besides running a continuous real-time search for a burst of neutrinos in its own data, NOvA subscribes to the Supernova Early Warning System, or SNEWS, a network of neutrino experiments that alert each other when any two of them see supernova-like activity at the same time. NOvA also subscribes to alerts sent by the LIGO/Virgo collaboration when a gravitational-wave event is observed, treating each one as a potential source of interesting data. Since gravitational-wave astronomy is brand new, there is great potential for surprises.

The simplest model explaining the majority of gravitational-wave events — black holes merging in vacuum — does not predict particle emissions. But if the black holes merged within a gaseous medium, particles would be accelerated, possibly leading to an observable signal. Other more exotic alternative models explaining some gravitational-wave events could also yield a burst of particles visible to NOvA.

Another scenario that could trigger NOvA is a case of mistaken identity, one in which a supernova is misidentified as a black hole gravitational-wave event. The collaboration performed a search for any emissions visible to NOvA, ranging from supernova-like neutrinos up to high-energy particle showers large enough to light up the entire far detector. As yet, using two dozen gravitational wave events reported through mid-2019, NOvA has found no indication of a signal. This result appears in Physical Review D. NOvA will continue to examine events as they are reported. With the capabilities of gravitational-wave detectors set to rapidly improve over the next few years, there will be many more opportunities to participate in new discoveries.

Closer to home, the NOvA’s underground near detector has been used to examine the seasonal variation of cosmic-ray muons underground. Cosmic rays are particles from outer space that constantly rain down from the sky. They collide with particles in the upper atmosphere, producing muons. The number of muons is affected by atmospheric conditions, and the total number of muons reaching underground detectors is higher in the summer. Summer’s less dense atmosphere favors the production of muons, whereas the denser winter atmosphere tends to degrade the energy of the muons’ parent particles. NOvA is the second experiment, after its predecessor MINOS, to observe that this seasonal correlation is flipped when pairs of muons arriving simultaneously, instead of lone muons, are counted. These are more common in the winter for reasons not well understood.

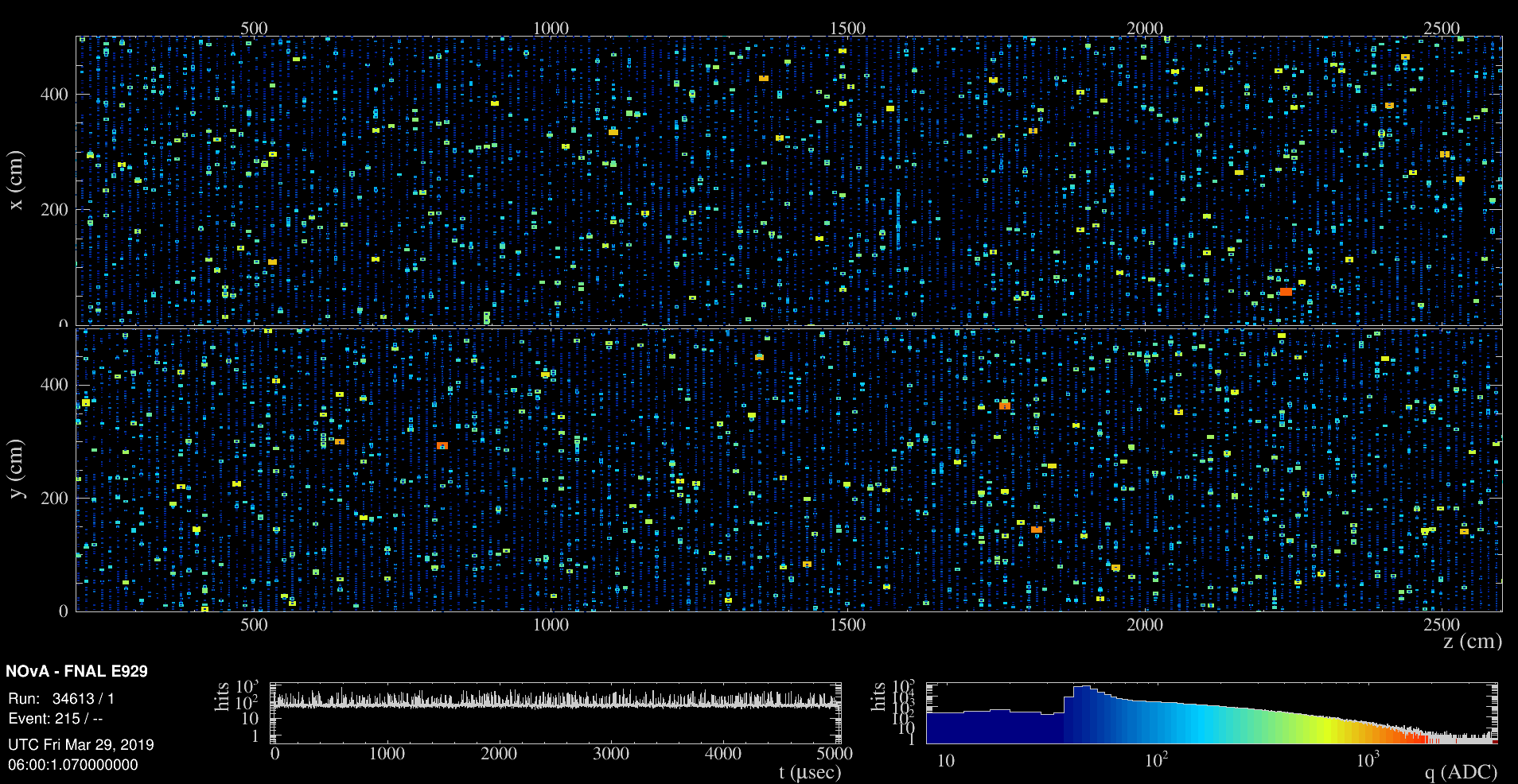

If Betelgeuse went supernova, data in the NOvA far detector would look similar to what is shown in this simulated event display. The larger yellow and orange squares show the simulated response to neutrinos, while the small blue squares are noise. Image: NOvA collaboration

NOvA also uses its large far detector to look for other exotic cosmic phenomena. In a new paper on the arXiv, the collaboration reports on a search for magnetic monopoles. These hypothetical particles carry a single magnetic charge — either a north or a south pole, but not both. Never observed, the existence of monopoles would help tie together fundamental theories in physics, as well as bring a satisfying symmetry to Maxwell’s equations describing electromagnetism. Magnetic monopoles may be a rare component of cosmic rays, and the NOvA far detector is a very capable cosmic-ray detector, able to observe detailed particle tracks. Unlike most previous neutrino detectors and many previous monopole detectors, it is not underground. This means that if monopoles turn out to be relatively slow and light particles, they would reach NOvA, unlike detectors used in previous searches. Using a small set of early data, NOvA researchers searched for monopoles in a mass range never before searched. They saw none, ruling out a large flux of lightweight monopoles. They will examine further data to tighten these limits or, just maybe, to discover the elusive particle.

Nature’s cosmic accelerators continue providing interesting physics for the NOvA collaboration to study.

Matthew Strait is a University of Minnesota physicist on the NOvA neutrino experiment.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.