How long have you worked at Fermilab?

A little over 14 years.

What brought you to Fermilab?

I used to work doing janitorial service, and I was looking for a better job. When I started working here, I helped the herdsman here at the time. I have a little background in cattle; I helped my uncle down in Mexico. So it’s almost the same. Then the herdsman left, and because I worked with him, they put me in charge of the animals. That was in 2010.

What’s a normal day like for you?

The first thing I do is come check on the animals, especially now in the calving season. Then I check fences or mow the grass or do some other Roads and Grounds chores. We try to let the bison roam freely by themselves within the pastures. It’s only in the winter when we supplement their diet with hay and grain. Otherwise we let them graze on their own.

What are the trickiest parts of the job?

There’s a day in the fall when we do vaccinations, and everybody helps out. We have to corral them, put them through a squeeze chute one by one, and tag the new ones or vaccinate the cows. You have to be really careful. The bison are really strong animals. We’re never inside the corrals ourselves, but when you’re moving the animals, they can react and charge you. We have a machine to move them around safely.

Have you ever been hurt?

No. It’s one of the jobs where you have to be very careful.

What do you like best about the job?

There’s always something new. I guess I’m not an office guy or a factory guy. I sometimes help with tours, and when you see the excitement of people looking at the calves, it makes you proud of what you’re doing. A lot of people from surrounding areas come just to see the bison.

What do your friends think when they find out what you do?

Sometimes they don’t even believe it. They don’t know there are bison here at Fermilab.

What do you like to do in your free time?

I like to camp with friends and family, and I support my children in sports activities. I enjoy spending my extra time working in my garden. I don’t think I could ever work inside. I like the outdoors.

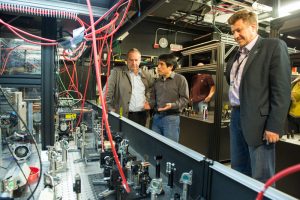

Fermilab accelerator scientist Jinhao Ruan (center) shows Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer (left) the laser setup for the FAST photoinjector. Vladimir Shiltsev (right) is director of the Fermilab Accelerator Physics Center. Photo: Reidar Hahn

On May 16, Fermilab sent an electron beam with an energy of 50 million electronvolts, or MeV, through the photoinjector at the Fermilab Accelerator Science and Technology facility (FAST), achieving a major design goal for the accelerator – and marking the beginning of a new accelerator science program at the laboratory.

“This is a major milestone for our general accelerator R&D,” said Vladimir Shiltsev, head of the Fermilab Accelerator Physics Center. “The delivery of this beam marks the start of a new program here – new facility, new science capabilities.”

The delivery of 50-MeV beam is the first step in establishing an accelerator R&D facility that will serve as one of America’s leading test beds for cutting-edge, record-high-intensity particle beam research. Once complete, FAST will provide scientists and engineers from around the world with a place to study the science of high-intensity particle beams and superconducting radio-frequency acceleration, the technology on which nearly all future high-energy accelerators are based.

The photoinjector is just the first phase of a larger accelerator to be built at FAST, which is supported by the DOE Office of Science. It will include a superconducting linear accelerator and a particle storage ring called the Integrable Optics Test Accelerator, or IOTA, which will be built over the next two years.

Although the photoinjector is just the front section of what will become a higher-energy accelerator, it still provides enough beam to be useful for carrying out scientific research. In fact, the first accelerator physics researchers to sign up for time at the facility have now begun using the electron beam. The inaugural group, led by Northern Illinois University professors Philippe Piot and Swapan Chattopadhyay, has reserved two months of beam time as part of the Fermilab-NIU Research Cluster.

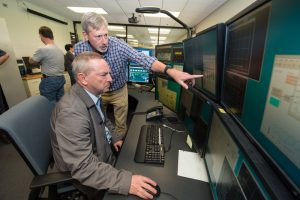

In the FAST control room and under the guidance of Fermilab scientist Elvin Harms (standing), Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer turns on the upgraded superconducting radio-frequency cavity, called CC1. Photo: Reidar Hahn

For FAST to produce the kinds of beams that are useful for accelerator R&D, its initial electron beam had to have an energy of 50 MeV. In 2015, Fermilab delivered a 20-MeV electron beam. Since then, scientists, engineers and technicians have upgraded the photoinjector to meet specifications, including installing a refurbished accelerating cavity that had been used elsewhere on the Fermilab site.

“It takes a significant effort to install all the complex components and subsystems that make up such an accelerator, and everything has to be done just right,” said Jerry Leibfritz, project engineer for FAST. “The fact that both 20-MeV and 50-MeV beams were achieved within a day or two of the start of commissioning is truly a testament to the excellent work and dedication of all those involved in this project.”

In the current setup, electron bunches generated by a laser are accelerated through two superconducting accelerating cavities (including the refurbished cavity), which bring the energy of electrons to 50 MeV.

As work on FAST progresses, the electron beam will continue through another eight superconducting radio-frequency cavities, accelerating to 300 MeV before entering the beamline for IOTA.

“FAST represents the beginning of a new era at Fermilab, in which the study and development of high-intensity particle beams become an important and productive part of the laboratory program,” said Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer.

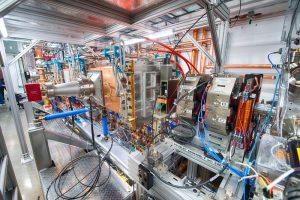

They stand by their work: PIP-II collaborators stand next to the doublet magnet, built by BARC, for the PIP-II medium-energy beam transport. From left: Michael Tartaglia (Fermilab), Joseph DiMarco (Fermilab), Vikas Teotia (BARC), Alexander Shemyakin (Fermilab), Curtis Baffes (Fermilab), Shekhar Mishra (Fermilab). Photo: Reidar Hahn

Building particle accelerators for high-energy physics is an international affair, and Fermilab’s future PIP-II accelerator is no exception. Week in and week out, two teams of accelerator scientists and engineers two oceans apart work to design and produce components for two future machines, one in India, and one at Fermilab.

The partnership recently bore its first, tangible fruit: preproduction magnets designed and built at Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), in Mumbai, India. The magnets were installed and tested at the Fermilab PIP-II Injector Test Accelerator in late March.

The installation of these magnets – four quadrupole focusing lenses and two dipole correctors – is just the start of an important collaboration with BARC on PIP-II, drawing together research groups from opposite sides of the world.

Since January 2015, the two laboratories have been regularly accommodating the half-day time difference, making late-night or early-morning conference calls, to realize dreams of two countries for high-power accelerators.

“BARC has really stepped up in taking the responsibility for designing and fabricating these magnets, delivering them in a timely manner,” said Shekhar Mishra, deputy project manager for PIP-II. “We gain a great deal from the partnership with Indian laboratories, which is critical to the success of our accelerator-based physics program.”

More BARC magnets will find a home in a section of PIP-II called the Medium-Energy Beam Transport (MEBT), through which a beam of negatively charged hydrogen ions will travel at 2.1 million electronvolts. BARC is building a total of 16 dipole and 34 quadrupole magnets, which will guide and focus the particle beam.

BARC rigorously tested the first set of magnets for their magnetic, electric and thermal qualifications, making sure they met PIP-II specifications before they delivered them to Fermilab, where both BARC and Fermilab scientists tested them once again.

The magnets worked as expected. The beam, guided by the magnets, went through the first portion of the MEBT with no measurable losses.

BARC’s two preproduction quadrupoles (with labels B and C) and dipole (with the copper winding) for PIP-II are visible toward the right of the picture. Photo: Reidar Hahn

The collaboration between BARC and Fermilab extends well beyond accelerator magnet development to include all key areas of the PIP-II Superconducting Linac. BARC scientists and engineers – many of whom are young, early-career scientists – have wide-ranging skills that dovetail with Fermilab expertise in superconducting radio-frequency technology, on which most future high-energy accelerators are based.

“This will help us gear up for meeting future challenges,” said Sanjay Malhotra, subproject coordinator at BARC for the Indian Institutions and Fermilab Collaboration. They include developing components for accelerator applications in Indian industry.

BARC plans to send the next batch of magnets in July and finish the delivery by the end of 2016.

The Fermilab-BARC partnership is part of the umbrella Indian Institutions and Fermilab Collaboration, which Mishra helped establish. The IIFC works with the U.S. Department of Energy to develop research facilities at Fermilab and accelerator projects at Indian Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) laboratories. Thirteen subprojects at Fermilab are conducted under the aegis of IIFC, and all are on schedule.

“Thanks to the excellent support and vision of the management and international coordinators at DAE and Fermilab, our collaborative programs have been running quite smoothly,” Malhotra said. “The technical teams on both sides have worked diligently to ensure that the collaboration runs seamlessly on both sides.”

What could be better than spending a fun-filled day outdoors and learning about natural science at the same time?

For the ninth year in a row, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is inviting families, scout troops and other youth groups to attend the Family Outdoor Fair on Sunday, June 12, from 1-4 p.m. The fair takes place outside the Lederman Science Center and highlights the plant and animal life found on the 6,800-acre Fermilab site in Batavia.

More than a dozen outdoor activities are planned for the fair, including a prairie scavenger hunt and a visit with Fermilab’s herd of bison. Kids can test whether they can run as fast as a bison, can sweep for insects and other critters, and thanks to the Naperville Astronomical Association, safely get a long look at the sun.

Once again, the Northern Illinois Raptor Rehabilitation and Education Center, along with local raptor trainers, will be on hand with live hawks, falcons and owls, as well as a collection of bird bones, feathers and hunting gear for children to enjoy.

“We want kids to come away with an appreciation of nature,” said Sue Sheehan of the Fermilab Education Office. “There’s so much to see. We want to show kids and parents that science is everywhere, even in their own back yards.”

Of course, their back yards aren’t quite as vast as Fermilab’s. More than 1,000 acres of the laboratory site is restored natural prairie, and the U.S. Department of Energy has designated Fermilab a National Environmental Research Park.

The Family Outdoor Fair is geared for first through seventh grade students. The fair is free and will take place rain or shine. Members of the media are welcome to attend. No registration is required. For more information, call 630-840-5588 or email edreg@fnal.gov.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.