At a recent physics seminar at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Fermilab physicist Pat Lukens of the CDF experiment announced the observation of a new particle, the Omega-sub-b (Ωb). The particle contains three quarks, two strange quarks and a bottom quark (s-s-b). It is an exotic relative of the much more common proton and has about six times the proton’s mass.

The observation of this “doubly strange” particle, predicted by the Standard Model, is significant because it strengthens physicists’ confidence in their understanding of how quarks form matter. In addition, it conflicts with a 2008 result announced by CDF’s sister experiment, DZero.

The Omega-sub-b is the latest entry in the “periodic table of baryons.” Baryons are particles formed of three quarks, the most common examples being the proton and neutron. The Tevatron particle accelerator at Fermilab is unique in its ability to produce baryons containing the b quark, and the large data samples now available after many years of successful running enable experimenters to find and study these rare particles. The observation opens a new window for scientists to investigate its properties and better understand this rare object.

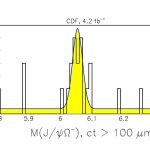

Combing through almost half a quadrillion (1000 trillion) proton-antiproton collisions produced by Fermilab’s Tevatron particle collider, the CDF collaboration isolated 16 examples in which the particles emerging from a collision revealed the distinctive signature of the Omega-sub-b. Once produced, the Omega-sub-b travels a fraction of a millimeter before it decays into lighter particles. This decay, mediated by the weak force, occurs in about a trillionth of a second. In fact, CDF has performed the first ever measurement of the Omega-sub-b lifetime and obtained 1.13 +0.53-0.40 (stat.) ±0.02(syst.) trillionths of a second.

In August 2008, the DZero experiment announced its own observation of the Omega-sub-b based on a smaller sample of Tevatron data. Interestingly, the new CDF observation announced here is in direct conflict with the earlier DZero result. The CDF physicists measured the Omega-sub-b mass to be 6054.4 ±6.8(stat.) ±0.9(syst.) MeV/c2, compared to DZero’s 6165±10(stat.)±13(syst.) MeV/c2. These two experimental results are statistically inconsistent with each other leaving scientists from both experiments wondering whether they are measuring the same particle. Furthermore, the experiments observed different rates of production of this particle. Perhaps most interesting is that neither experiment sees a hint of evidence for the particle at the other’s measured value.

Although the latest result announced by CDF agrees with theoretical expectation for the Omega-sub-b both in the measured production rate and in the mass value, further investigation is needed to solve the puzzle of these conflicting results.

The Omega-sub-b discovery follows the observation of the Cascade-b-minus baryon (Ξb), first observed at the Tevatron in 2007, and two types of Sigma-sub-b baryons (Σb), discovered at the Tevatron in 2006.

The CDF collaboration submitted a paper that summarizes the details of its discovery to the journal Physical Review D. It is available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/0905.3123

CDF is an international experiment of about 600 physicists from 62 institutions in 15 countries. It is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and a number of international funding agencies. Fermilab is a national laboratory funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC.

- Six quarks–up, down, strange, charm, bottom and top–are the building blocks of matter. Protons and neutrons are made of up and down quarks, held together by the strong nuclear force. The CDF experiment now has observed the Omega-sub-b particle, which contains two strange quarks (s) and one bottom quark (b).

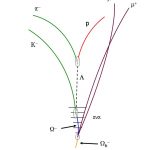

- Once produced, the Omega-sub-b (Ωb) particle travels about a third of a millimeter before it disintegrates into two intermediate particles called J/Psi (J/ψ) and Omega-minus (Ω-). The J/Psi then promptly decays into a pair of muons. The Omega-minus baryon, on the other hand, can travel several centimeters and occasionally be measured in the CDF silicon vertex detector. The particle decays into an unstable particle called a Lambda (Λ) baryon along with a long-lived kaon particle (K). The Lambda baryon, which has no electric charge, also can travel several centimeters prior to decaying into a proton (p) and a pion (π). Credit: CDF collaboration.

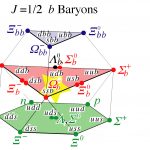

- Baryons are particles made of three quarks. The quark model predicts the combinations that exist with either spin J=1/2 (this graphic) or spin J=3/2. The graphic shows the various three-quark combinations with J=1/2 that are possible using the three lightest quarks–up, down and strange–and the bottom quark. The CDF collaboration observed the Omega-sub-b, highlighted in the graphic. There exist additional baryons involving the charm quark, which are not shown. The top quark, discovered at Fermilab in 1995, is too short-lived to become part of a baryon.

- The CDF collaboration has observed 16 Omega-sub-b candidates in the data collected through October 2008. The mass of the Omega-sub-b is measured to be 6054.4 ± 6.8 MeV/c2. The lifetime of the Omega-sub-b is measured to be 1.13 ± 0.53 picoseconds. Credit: CDF collaboration.

- The Fermilab accelerator complex accelerates protons and antiprotons close to the speed of light. Converting energy into mass, the Tevatron collider can produce particles that are heavier than the protons and antiprotons that are colliding. The Tevatron produces millions of proton-antiproton collisions per second, maximizing the chance for discovery. Two experiments, CDF and DZero, search for new types of particles emerging from the collisions.

- The CDF detector, about the size of a 3-story house, weighs about 6,000 tons. Its subsystems record the “debris” emerging from high-energy proton-antiproton collisions. The detector surrounds the collision point and records the path, energy and charge of the particles emerging from the collisions. This information can be used to find and determine the properties of the Omega-sub-b particle.

- Some of the 600 scientists of the CDF collaboration in front of Wilson Hall at Fermilab.

CERN Director-General Rolf Heuer, Nobel Laureate Leon Lederman and Fermilab physicist Boris Kayser answer questions about antimatter, the Large Hadron Collider and particle physics research

The U.S. National Science Foundation invites you to join a live media briefing on the science behind the motion picture Angels & Demons on May 19 at 1:00 p.m. EDT (12 noon CDT; 7:00 p.m. CEST). This blockbuster film, which gives particle physics a moment on the red carpet, hits movie screens around the world this week. The briefing will feature three world-renowned physicists from the European particle physics laboratory CERN and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

Based on Dan Brown’s best-selling novel, Angels & Demons focuses on a plot to destroy the Vatican using a small amount of antimatter. That antimatter is made using the Large Hadron Collider and is stolen from CERN. Parts of the movie were filmed at CERN.

The briefing, a live video teleconference, will feature Rolf Heuer, director-general at CERN, Leon Lederman, Nobel laureate and director emeritus at Fermilab, and Boris Kayser, Fermilab physicist and chair of the American Physics Society’s Division of Particles and Fields. To watch and ask questions during the briefing, visit the Science 360 Web site (http://www.science360.gov/live/). Journalists should send an email to lisajoy@nsf.gov to obtain a call-in number and passcode. Anyone can submit questions any time to webcast@nsf.gov.

This media briefing is part of a larger worldwide event: “Angels & Demons Lecture Nights: the Science Revealed.” More information about the series, including a list of lectures and local contacts, is available at www.uslhc.us/Angels_Demons.

* U.S. participation in the Large Hadron Collider project is supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation.

* CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, is the world’s leading laboratory for particle physics. It has its headquarters in Geneva. At present, its Member States are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. India, Israel, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States of America, Turkey, the European Commission and UNESCO have Observer status.

* Fermilab is a Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the nation and helps ensure U.S. world leadership across a broad range of scientific disciplines.

Ash River, Minn. – Construction begins this month on a cutting-edge physics laboratory in northern Minnesota, supported by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Congressman James Oberstar of Minnesota and Congressman Bill Foster of Illinois today (May 1) are joining officials from the U.S. Department of Energy, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and the University of Minnesota to break ground for NOvA, the world’s most advanced neutrino experiment.

“This project is part of a bold, visionary initiative which will have profound implications for our understanding of the structure and evolution of the universe,” Congressman Oberstar said. “The billion-year-old rock formations in Northeast Minnesota are helping researchers unlock mysteries of the origins of the universe.”

The DOE Office of Science has provided $40.1 million in Recovery Act funding for the construction project. It will provide an additional $9.9 million in Recovery Act funding to Fermilab, which manages the project, for purchasing key high-tech components for the project from U.S. companies, enabling those firms to retain and hire workers.

Community members also are gathering in nearby Orr, Minn., for a public presentation about the project and its impact on the local community.

The NOvA project will construct the NuMI Off-Axis Electron Neutrino Appearance (NOvA) detector facility, a laboratory of the University of Minnesota’s School of Physics and Astronomy, near the Ash River, about 40 miles southeast of International Falls. The lab will house a 15,000-ton particle detector that will investigate the role of subatomic particles called neutrinos in the origin of the universe.

“The NOvA project will fundamentally expand our understanding of neutrinos, but it will also help strengthen scientific partnerships between the University of Minnesota and Fermilab in my district,” Congressman Foster said. “Fermilab is where much of detector equipment is being built, and the neutrino beams also originate at Fermilab. This project represents the kind of investment that simultaneously supports basic scientific research, our national labs and our economy.”

Construction of the facility, supported under a cooperative agreement for research between the U.S. Department of Energy and the University of Minnesota, is expected to generate 60 to 80 jobs. In addition, the construction will result in procurements for concrete, steel, road-building materials and mechanical and electrical equipment from U.S. firms.

“The NOvA project is an investment in our scientific future that will help us to better understand the role that neutrinos have played in the evolution of the universe,” said Dennis Kovar, DOE Associate Director of Science for High Energy Physics. “NOvA’s groundbreaking reaffirms America’s commitment to retaining its position of leadership in accelerator-based particle physics.”

The NOvA project involves about 180 scientists and engineers from 28 institutions. The collaboration will build the neutrino detector and install it in the new laboratory. When the detector is completed, physicists will explore the mysterious behavior of neutrinos by examining pulses of neutrinos sent straight through the earth from Fermilab in Illinois to the NOvA detector facility in Minnesota. The neutrinos travel the 500 miles in less than three milliseconds.

“The planning for the NOvA Facility has been years in the making, and we’re very excited that it is becoming a reality,” said University of Minnesota physics professor Marvin Marshak, a lead faculty member on the project. “This project will provide tremendous opportunities for University of Minnesota faculty and students to work with experts from around the world on important research.”

The new laboratory expands the university’s international reputation as a leader in neutrino research. The University of Minnesota currently runs the Soudan Underground Laboratory near Tower, Minn., the only laboratory of its kind in the United States. For more information about the NOvA groundbreaking, please visit http://www.fnal.gov/nova/.

For additional information about the NOvA experiment, please see http://www-nova.fnal.gov/fermilab_nova.pdf

Fermilab is a Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the nation and helps ensure U.S. world leadership across a broad range of scientific disciplines.

- This rendering depicts the future NOvA detector facility on the property in Ash River, Minnesota, about 40 miles southeast of International Falls. Rendering by Holabird & Root

- Members of the NOvA collaboration pose during a collaboration meeting the weekend of April 24, 2009. Photo: George Joch of Argonne National Laboratory

- Ash River near the future site of the NOvA detector facility. Photoa; William Miller, NOvA installation manager

- A rendering of the entrance to the NOvA detector facility. Physicists will use the NOvA experiment to analyze the mysterious behavior of neutrinos sent through the Earth from Fermilab in Illinois to the NOvA detector in Ash River, Minnesota. Rendering by Holabird & Root

Parents looking for a way to get their children outdoors and for them to have fun with hands-on science activities have an event to add to their calendar. This year’s Family Outdoor Activity Fair at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory will take place from 1 to 4 p.m. on Sunday, April 26. The event is free and open to the public, but registration is required: fair participants need to send an email with the number of children and adults attending the event to edreg@fnal.gov.

The outdoor activity fair will offer more than a dozen activities for children ages 5-12. Older children can make their own sun dial while younger children can identify animal tracks. Everyone also can enjoy a presentation of live birds of prey. Children can explore the wildlife living in ponds and on logs and visit the bison pen to check for new calves.

“Science doesn’t just have to happen in a lab,” said Gail Poisson, event co-organizer. “We want to show parents and their children science is everywhere.”

This is the second year for the fair, which began as a way to help parents get their children excited about science. The event is funded by the Supporting Parents in Advocacy, Reform and Knowledge in Science program.

Fermilab is a Department of Energy national laboratory operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the nation and helps ensure U.S. world leadership across a broad range of scientific disciplines.

Batavia, Ill.—The U.S. Department of Energy has named the U.S. Compact Muon Solenoid detector project as a recipient of the DOE Secretary’s Award for Achievement. DOE presents the awards to management teams that demonstrate significant results in completing projects within cost and schedule. Fermilab physicist Dan Green will accept the award on behalf of the U.S. CMS collaboration on March 31, at the 2009 Annual DOE Project Management Workshop in Alexandria, Virginia.

The U.S. CMS collaboration will share the award for the detector project with the U.S. ATLAS collaboration. The projects provide a unique opportunity for U.S. scientists to participate in the largest collaborative effort ever attempted in the physical sciences. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory serves as the host laboratory for the U.S. CMS project. Brookhaven National Laboratory hosts the U.S. ATLAS project. Scientists from U.S. universities and national laboratories contributed key components and expertise to the state-of-the-art detectors built for the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics, in Geneva, Switzerland.

“This award is a tribute to the entire U.S. CMS collaboration,” said Green, who currently serves as the CMS Collaboration board chair. “It recognizes the team efforts of more than 700 scientists who built one-third of the detector on time and on budget.

CMS has approximately 2,300 international collaborators. Supported by the DOE Office of Science and the National Science Foundation, the U.S. CMS collaboration consists of roughly 420 Ph.D. physicists, over 100 graduate students and nearly 200 engineers, technicians, and computer scientists from 48 U.S. universities and Fermilab. The U.S. is the largest single national group in the experiment.

“I congratulate Fermilab and Dan Green on effectively managing the U.S. CMS detector project,” said Pepin Carolan, who served as DOE Federal Project Director for U.S. CMS and U.S. ATLAS. “Both U.S. ATLAS and U.S. CMS play a critical role in training future generations of scientists to maintain U.S. leadership in science, technology and innovation.”

Notes for editors:

Press kits are available at:

http://www.uscms.org/public_2/about/press_kit/index.shtml

The United States contributions to the CMS experiment and the Large Hadron Collider are funded by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation.

CERN is the European Organization for Nuclear Research, with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. At present, its Member States are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. India, Israel, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States of America, Turkey, the European Commission and UNESCO have Observer status.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is the host laboratory for the US CMS Collaboration. Fermilab is a Department of Energy National Laboratory operated under a contract with DOE by the Fermi Research Alliance for the DOE Office of Science.

U.S. CMS member institutions

(48 institutions, from 23 states and Puerto Rico)

California

California Institute of Technology, Pasadena

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore

University of California, Davis

University of California, Los Angeles

University of California, Riverside

University of California, San Diego

University of California, Santa Barbara

Colorado

University of Colorado, Boulder

Connecticut

Fairfield University, Fairfield

Florida

Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne

Florida International University, Miami

Florida State University, Tallahassee

University of Florida, Gainesville

Illinois

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia

Northwestern University, Evanston

University of Illinois at Chicago

Indiana

Purdue University, West Lafayette

Purdue University Calumet, Hammond

University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame

Iowa

University of Iowa, Iowa City

Kansas

Kansas State University, Manhattan

University of Kansas, Lawrence

Maryland

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

University of Maryland, College Park

Massachusetts

Boston University, Boston

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge

Northeastern University, Boston

Michigan

Wayne State University, Detroit

Minnesota

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

Mississippi

University of Mississippi, Oxford

Nebraska

University of Nebraska, Lincoln

New Jersey

Princeton University, Princeton

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway

New York

Cornell University, Ithaca

Rockefeller University, New York

State University of New York at Buffalo

University of Rochester, Rochester

Ohio

Ohio State University, Columbus

Pennsylvania

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh

Puerto Rico

University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez

Rhode Island

Brown University, Providence

Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Vanderbilt University, Nashville

Texas

Rice University, Houston

Texas A&M University, College Station

Texas Tech University, Lubbock

Virginia

University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Wisconsin

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Funds are part of $1.2 billion from Recovery Act to be disbursed by Department of Energy’s Office of Science

Batavia, Ill.—In the first installment of funding from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science under President Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory will receive $34.9 million.

The funds are part of $1.2 billion announced by Secretary of Energy Steven Chu today from funding allocated under the Recovery Act to DOE’s Office of Science. The funds will support an array of Office of Science-sponsored construction, laboratory infrastructure, and research projects across the nation. The Secretary made the announcement during a visit to Brookhaven National Laboratory, in Upton, NY.

“Leadership in science remains vital to America’s economic prosperity, energy security, and global competitiveness,” said Secretary Chu. “These projects not only provide critically needed short-term economic relief but also represent a strategic investment in our nation’s future. They will create thousands of jobs and breathe new life into many local economies, while helping to accelerate new technology development, renew our scientific and engineering workforce, and modernize our nation’s scientific infrastructure.”

The Fermilab allocation is part of $1.2 billion that Secretary Chu announced is being disbursed now in the first installment of a total of $1.6 billion allocated to the DOE Office of Science by Congress under the Recovery Act legislation. Officials are working on details remaining to enable approval and release of the balance of $371 million.

Fermilab will invest the funds in critical scientific infrastructure to strengthen the nation’s global scientific leadership as well as to provide immediate economic relief to local communities. The laboratory will use $25 million for construction and improvement projects that will generate engineering and construction jobs in Illinois businesses and pay for materials and services purchased from U.S. companies. The laboratory will devote the remaining $9.9 million to purchasing key high-tech components from U.S. companies for the NOvA neutrino project, allowing these firms to retain and hire workers.

In addition to the $34.9 million for Fermilab, the initial round of Office of Science funding provides $40.1 million to the University of Minnesota for construction of the Fermilab-managed NOvA neutrino experiment. The NOvA funding for Minnesota will generate an estimated 60-plus construction jobs and procurements for concrete, steel, road-building materials and mechanical and electrical equipment from U.S. firms.

“At Fermilab, we are committed to put Recovery Act funding to work in the way the nation intends: to strengthen our country’s long-term future by investment in basic science and to provide immediate economic help for our local communities and the nation by creating jobs and buying materials and services,” said Fermilab Director Pier Oddone. “We are ready to move forward today.”

DOE’s news release is available at www.energy.gov

This isn’t your average field trip. This month, more than 6,000 high school students participating in Hands-on Particle Physics Masterclasses will have the chance to form national or international scientific collaborations, just like real particle physicists do.

With the help of particle physicists, about 400 students from across the United States will analyze data from large particle collider experiments at CERN, the European Center for Nuclear Research. Most students will participate in this activity at universities and research institutes near their schools.

Classroom groups will discuss their findings via videoconference with other groups of students from across the country or across the globe. Physicists at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, including the laboratory’s deputy director, Young-Kee Kim, will help moderate videoconferences.

“This is a great opportunity to give students a deeper understanding of particle physics,” Kim said. “I hope this program will inspire them.”

This year high school students from around the world will participate in the international Hands-on Particle Physics Masterclass program, which began in Europe in 2005 and has expanded into the United States, South Africa and Brazil. Scientists at more than 100 universities and laboratories in 23 countries, including 22 institutions in the United States, will host students.

Students in the United States will participate through QuarkNet, a national program that unites high school students, physics teachers and particle physicists.

The opportunity to experience state-of-the-art research in an authentic environment will give students insight into the international organization of modern research. At the same time, they will learn about the building blocks of our universe through presentations by scientists involved in particle physics research.

“The Masterclass gives students the opportunity to understand the way physicists do high-energy physics,” said Jeff Rylander, instructional supervisor for the science department at Glenbrook South High School in Glenbrook, Ill. Rylander brought eight of his students to Argonne National Laboratory for a Masterclass last year and worked with a particle physicist from Fermilab.

“They appreciated looking at real data and interacting with a real physicist,” he said.

Summer Blot, now a physics student at the University of Chicago, attended the Masterclass last year with her QuarkNet group at Mills E. Goodwin High School in Richmond, Va. “It was neat that after only about an hour or two of learning how to do it, we were able to try analyzing data,” she said. “It made me realize that this is really what I want to do.”

Most students have to wait until graduate school to do that kind of data analysis, Blot said. “The fact that I have experience with it starting my first year is amazing to a lot of people. It gave me an advantage.”

This year’s lectures will discuss the Large Hadron Collider, the particle accelerator about 17 miles in circumference at the border of Switzerland and France. Students will analyze visual displays of real data collected at LEP, the previous large particle accelerator at CERN, and simulated data produced by the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider.

The Hands-on Particle Physics student research days take place under the central coordination of Physics Professor Michael Kobel, Technical University of Dresden, in close cooperation with the European Particle Physics Outreach Group and with the support of the Helmholtz Alliance “Physics at the Terascale,” and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research BMBF.

QuarkNet is funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

For editors:

The European Particle Physics Outreach Group is an independent committee of representatives of CERN member states and the research laboratories CERN and DESY. The committee’s goal is to make particle physics more accessible to the public. For more information: http://eppog.web.cern.ch/eppog/

For more information on the Hands-on Particle Physics Masterclasses: http://www.physicsmasterclasses.org

International schedule: http://www.physicsmasterclasses.org/mc/schedule.htm

U.S. schedule: http://cosm.hamptonu.edu/vlhc

For more information on QuarkNet and the Fermilab Education Office: http://www-ed.fnal.gov/ed_home.html

Batavia, Ill.—Scientists of the CDF experiment at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory announced yesterday (March 17) that they have found evidence of an unexpected particle whose curious characteristics may reveal new ways that quarks can combine to form matter. The CDF physicists have called the particle Y(4140), reflecting its measured mass of 4140 megaelectron volts. Physicists did not predict its existence because Y(4140) appears to flout nature’s known rules for fitting quarks and antiquarks together.

“It must be trying to tell us something,” said CDF cospokesperson Jacobo Konigsberg of the University of Florida. “So far, we’re not sure what that is, but rest assured we’ll keep on listening.”

Matter as we know it comprises building blocks called quarks. Quarks fit together in various well-established ways to build other particles: mesons, made of a quark-antiquark pair, and baryons, made of three quarks. So far, it’s not clear exactly what Y(4140) is made of.

The Y(4140) particle decays into a pair of other particles, the J/psi and the phi, suggesting to physicists that it might be a composition of charm and anticharm quarks. However, the characteristics of this decay do not fit the conventional expectations for such a make-up. Other possible interpretations beyond a simple quark-antiquark structure are hybrid particles that also contain gluons, or even four-quark combinations.

The CDF scientists observed Y(4140) particles in the decay of a much more commonly produced particle containing a bottom quark, the B + meson. Sifting through trillions of proton-antiproton collisions from Fermilab’s Tevatron, CDF scientists identified a small sampling of B+ mesons that decayed in an unexpected pattern. Further analysis showed that the B+ mesons were decaying into Y(4140).

The Y(4140) particle is the newest member of a family of particles of similar unusual characteristics observed in the last several years by experimenters at Fermilab’s Tevatron as well as at KEK laboratory in Japan and at DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California.

“We congratulate CDF on the first evidence for a new unexpected Y state that decays to J/psi and phi,” said Japanese physicist Masanori Yamauchi, a cospokesperson of KEK’s Belle experiment. “This state may be related to the Y(3940) state discovered by Belle and might be another example of an exotic hadron containing charm quarks. We will try to confirm this state in our own Belle data.”

Theoretical physicists are trying to decode the true nature of these exotic combinations of quarks that fall outside our current understanding of mesons and baryons. Meanwhile experimentalists happily continue to search for more such particles.

“We’re building upon our knowledge piece by piece,” said CDF cospokesperson Rob Roser of Fermilab, “and with enough pieces, we’ll understand how this puzzle fits together.”

The Y(4140) observation is the subject of an article submitted by CDF to Physical Review Letters this week. Besides announcing Y(4140), the CDF experiment collaboration is presenting more than 40 new results at the Moriond Conference on Quantum Chromodynamics in Europe this week, including the discovery of electroweak top-quark production and a new limit on the Higgs boson, in concert with experimenters from Fermilab’s DZero collaboration. Both experiments are actively pursuing a very broad program of physics, including ever-more-precise measurements of the top and bottom quarks, W and Z bosons and searches for additional new particles and forces.

“Thanks to the remarkable performance of the Tevatron, we expect to greatly increase our data sample in the next couple of years, said Konigsberg. “We’ll study better what we’ve found and hopefully make more discoveries. It’s a very exciting time here at Fermilab.”

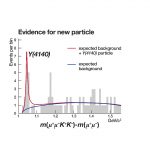

- The CDF collaboration found evidence for a new particle dubbed Y(4140), produced by the Tevatron collider at Fermilab. The particle’s signature peak became apparent when scientists analyzed the decay of particles that produce pairs of muons and pairs of K mesons, revealing a new particle structure. The Y particle has a mass of 4140 megaelectronvolts.

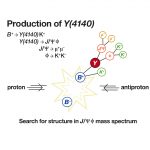

- The Tevatron typically produces about 10 million proton-antiproton collisions per second, sometimes creating particles known as B mesons. A B meson contains a quark-antiquark pair that includes either a bottom quark or anti-bottom quark. B mesons can decay directly into a J/Ψ (psi) particle and a Φ (phi) particle. The CDF scientists found evidence that some B mesons unexpectedly decay into an intermediate quark structure identified as a Y particle.

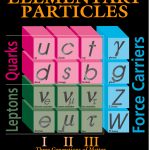

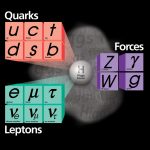

- The Standard Model of elementary particles and forces includes six quarks, which bound together to form composite particles. Physicists have an excellent understanding of how three quarks cluster together to form protons, neutrons and heavier baryons, and how a quark and anti-quark bind together to create pions, kaons and other mesons. But electron-positron colliders at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the Japanese laboratory KEK have revealed examples of composite quark structures–named X and Y particles–that are not the usual mesons and baryons. Now the CDF collaboration at Fermilab has found evidence for the Y(4140) particle.

- CDF physicist Kai Yi, University of Iowa, unveiled the evidence of the Y(4140) particle to scientists at Fermilab at seminar on March 17, 2009.

- The CDF detector, about the size of a 3-story house, weighs about 6,000 tons. Its subsystems record the “debris” emerging from high-energy proton-antiproton collisions. The detector surrounds the collision point and records the path, energy and charge of the particles emerging from the collisions. This information can be used to find and determine the properties of the Omega-sub-b particle.

- The Fermilab accelerator complex accelerates protons and antiprotons close to the speed of light. Two experiments, CDF and DZero, record the particles emerging from millions of collisions per second produced by the Tevatron collider. Each collision produces hundreds of particles.

Notes for Editors:

Fermilab is a Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the nation and helps ensure U.S. world leadership across a broad range of scientific disciplines.

CDF is an international experiment of about 602 physicists from 63 institutions in 13 countries. Funding for CDF comes from DOE’s Office of Science, the National Science Foundation, and a number of international funding agencies.

CDF collaborating institutions are at:

http://www-cdf.fnal.gov/collaboration/index.html

InterAction Collaboration media contacts:

A full list of worldwide InterAction media contacts is available at: http://www.interactions.org/presscontacts/

For more information on the InterAction Collaboration, visit www.interactions.org.

CDF, DZero experiments exclude significant fraction of Higgs territory

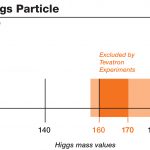

Batavia, Ill.—The territory where the Higgs boson may be found continues to shrink. The latest analysis of data from the CDF and DZero collider experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab now excludes a significant fraction of the allowed Higgs mass range established by earlier measurements. Those experiments predict that the Higgs particle should have a mass between 114 and 185 GeV/c2. Now the CDF and DZero results carve out a section in the middle of this range and establish that it cannot have a mass in between 160 and 170 GeV/c2.

“ The outstanding performance of the Tevatron and CDF and DZero together have produced this important result,” said Dennis Kovar, Associate Director of the Office of Science for High Energy Physics at the U.S. Department of Energy. “We’re looking forward to further Tevatron constraints on the Higgs mass.”

The Higgs particle is a keystone in the theoretical framework known as the Standard Model of particles and their interactions. According to the Standard Model, the Higgs boson explains why some elementary particles have mass and others do not.

So far, the Higgs particle has eluded direct detection. Searches at the Large Electron Positron collider at the European laboratory CERN established that the Higgs boson must weigh more than 114 GeV/c2. Calculations of quantum effects involving the Higgs boson require its mass to be less than 185 GeV/c2.

“A cornerstone of NSF’s support of particle physics is the search for the origin of mass, and this result takes us one step closer,” said Physics Division Director Joe Dehmer, of the National Science Foundation.

The observation of the Higgs particle is also one of the goals of the Large Hadron Collider experiments at CERN, which plans to record its first collision data before the end of this year.

The success of probing the Higgs territory at the Tevatron has been possible thanks to the excellent performance of the accelerator and the continuing improvements that the experimenters incorporate into the analysis of the collider data.

“Fermilab’s Tevatron collider typically produces about ten million collisions per second,” said DZero co-spokesperson Darien Wood, of Northeastern University. “The Standard Model predicts how many times a year we should expect to see the Higgs boson in our detector, and how often we should see particle signals that can mimic a Higgs. By refining our analysis techniques and by collecting more and more data, the true Higgs signal, if it exists, will sooner or later emerge.”

To increase their chances of finding the Higgs boson, the CDF and DZero scientists combine the results from their separate analyses, effectively doubling the data available.

“A particle collision at the Tevatron collider can produce a Higgs boson in many different ways, and the Higgs particle can then decay into various particles,” said CDF co-spokesperson Rob Roser, of Fermilab. “Each experiment examines more and more possibilities. Combining all of them, we hope to see a first hint of the Higgs particle.”

So far, CDF and DZero each have analyzed about three inverse femtobarns of collision data—the scientific unit that scientists use to count the number of collisions. Each experiment expects to receive a total of about 10 inverse femtobarns by the end of 2010, thanks to the superb performance of the Tevatron. The collider continues to set numerous performance records, increasing the number of proton-antiproton collisions it produces.

The Higgs search result is among approximately 70 results that the CDF and DZero collaborations presented at the annual conference on Electroweak Physics and Unified Theories known as the Rencontres de Moriond, held March 7-14. In the past year, the two experiments have produced nearly 100 publications and about 50 Ph.D.s that have advanced particle physics at the energy frontier.

- Scientists from the CDF and DZero collaborations at DOE’s Fermilab have combined Tevatron data from their two experiments to increase the sensitivity for their search for the Higgs boson. While no Higgs boson has been found yet, the results announced today exclude a mass for the Higgs between 160 and 170 GeV/c² with 95 percent probability. A larger area is excluded at the 90 percent probability level. Earlier experiments at the Large Electron-Positron Collider at CERN excluded a Higgs boson with a mass of less than 114 GeV/c² at 95 percent probability. Calculations of quantum effects involving the Higgs boson require its mass to be less than 185 GeV/c². The results show that CDF and DZero are sensitive to potential Higgs signals. The Fermilab experimenters will test more and more of the available mass range for the Higgs as their experiments record more collision data and as they continue to refine their experimental analyses.

- According to the Standard Model of particles and forces, the Higgs mechanism gives mass to elementary particles such as electrons and quarks. Its discovery would answer one of the big questions in physics: What is the origin of mass?

-

Med Res

Listen to CDF graduate student Barbara Alvarez-Gonzalez, University of Oviedo, as she explains in this 2-minute video the search for the Higgs particle with the CDF detector. Alvarez-Gonzalez is one of about 600 physicists from 63 institutions in 15 countries who work on the CDF experiment at Fermilab.

YouTube

Quicktime (8.5 mb)

Windows Media (11.6 mb)

Downloadable MPEG-4 (33.4 mb)

Embedded video is below.

-

Listen to DZero physicist Michael Kirby, Northwestern University, as he explains in this 2-minute video how DZero collects and analyses collision data to find signs of the Higgs particle. Kirby is one of about 550 physicists from 90 institutions in 18 countries who work on the DZero experiment at Fermilab.

YouTube

Quicktime (10.3 mb)

Windows Media (15.6 mb)

Downloadable MPEG-4 (46.4 mb)

Video also embedded below

- The Fermilab accelerator complex accelerates protons and antiprotons close to the speed of light. The Tevatron produces about ten million proton-antiproton collisions per second, maximizing the chance for discovery. Two experiments, CDF and DZero, search for new subatomic particles and forces unveiled by the collisions.

- The DZero detector records particles emerging from high-energy proton-antiproton collisions produced by the Tevatron. Tracing the particles back to the center of the collision, scientists understand the subatomic processes that take place at the core of proton-antiproton collisions. Scientists search for the tiny fraction of collisions that might have produced a Higgs boson.

- The CDF detector, about the size of a 3-story house, weighs about 6,000 tons. Its subsystems record the “debris” emerging from each high-energy proton-antiproton collision produced by the Tevatron. The detector records the path, energy and charge of the particles emerging from the collisions. This information can be used to look for particles emerging from the decay of a short-lived Higgs particle.

Notes for editors:

Fermilab, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory located near Chicago, operates the Tevatron, the world’s highest-energy particle collider. The Fermi Research Alliance LLC operates Fermilab under a contract with DOE.

CDF is an international experiment of 602 physicists from 63 institutions in 15 countries. DZero is an international experiment conducted by 550 physicists from 90 institutions in 18 countries. Funding for the CDF and DZero experiments comes from DOE’s Office of Science, the National Science Foundation, and a number of international funding agencies.

CDF collaborating institutions are at http://www-cdf.fnal.gov/collaboration/index.html

DZero collaborating institutions are at http://www-d0.fnal.gov/ib/Institutions.html

Batavia, Ill.—Scientists of the DZero collaboration at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have achieved the world’s most precise measurement of the mass of the W boson by a single experiment. Combined with other measurements, the reduced uncertainty of the W boson mass will lead to stricter bounds on the mass of the elusive Higgs boson.

The W boson is a carrier of the weak nuclear force and a key element of the Standard Model of elementary particles and forces. The particle, which is about 85 times heavier than a proton, enables radioactive beta decay and makes the sun shine. The Standard Model also predicts the existence of the Higgs boson, the origin of mass for all elementary particles.

Precision measurements of the W mass provide a window on the Higgs boson and perhaps other not-yet-observed particles. The exact value of the W mass is crucial for calculations that allow scientists to estimate the likely mass of the Higgs boson by studying its subtle quantum effects on the W boson and the top quark, an elementary particle that was discovered at Fermilab in 1995.

Scientists working on the DZero experiment now have measured the mass of the W boson with a precision of 0.05 percent. The exact mass of the particle measured by DZero is 80.401 +/- 0.044 GeV/c2. The collaboration presented its result at the annual conference on Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories known as Rencontres de Moriond last Sunday.

“This beautiful measurement illustrates the power of the Tevatron as a precision instrument and means that the stress test we have ordered for the Standard Model becomes more stressful and more revealing,” said Fermilab theorist Chris Quigg.

The DZero team determined the W mass by measuring the decay of W bosons to electrons and electron neutrinos. Performing the measurement required calibrating the DZero particle detector with an accuracy around three hundredths of one percent, an arduous task that required several years of effort from a team of scientists including students.

Since its discovery at the European laboratory CERN in 1983, many experiments at Fermilab and CERN have measured the mass of the W boson with steadily increasing precision. Now DZero achieved the best precision by the painstaking analysis of a large data sample delivered by the Tevatron particle collider at Fermilab. The consistency of the DZero result with previous results speaks to the validity of the different calibration and analysis techniques used.

“This is one of the most challenging precision measurements at the Tevatron,” said DZero co-spokesperson Dmitri Denisov, Fermilab “It took many years of efforts from our collaboration to build the 5,500-ton detector, collect and reconstruct the data and then perform the complex analysis to improve our knowledge of this fundamental parameter of the Standard Model.“

The W mass measurement is another major result obtained by the DZero experiment this month. Less than a week ago, the DZero collaboration submitted a paper on the discovery of single top quark production at the Tevatron collider. In the last year, the collaboration has published 46 scientific papers based on measurements made with the DZero particle detector.

- The Standard Model describes the interactions of the fundamental particle of the world around us. Experimental observations agree with the predictions of the Standard Model with high precision. The W boson, the carrier of the electroweak force, is a key element in these predictions. Its mass is a fundamental parameter relevant for many predictions, including the energy emitted by our sun to the mass of the elusive Standard Model Higgs boson, which provides elementary particles with mass. Credit: Fermilab

- Fermilab’s DZero collaboration obtained the world’s most precise W mass value measured by a single experiment and announced its result at the annual conference on Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories known as Rencontres de Moriond on March 8. Physicist Jan Stark, of the Laboratoire de Physique Subatomique in Grenoble, France, presented the result. Credit: DZero collaboration

- The DZero collaboration comprises about 550 scientists from 18 countries who designed and built the 5,500-ton DZero detector and now collect and reconstruct collision data. They research a wide range of Standard Model topics and search for new subatomic phenomena. Credit: DZero collaboration

- The Fermilab accelerator complex accelerates protons and antiprotons close to the speed of light. The Tevatron produces about ten million proton-antiproton collisions per second, maximizing the chance for discovery. Two experiments, CDF and DZero, search for new subatomic particles and forces unveiled by the collisions.

- The DZero detector records particles emerging from high-energy proton-antiproton collisions produced by the Tevatron. Tracing the particles back to the center of the collision, scientists understand the subatomic processes that take place at the core of proton-antiproton collisions. Scientists search for the tiny fraction of collisions that might have produced a Higgs boson.

Notes for Editors:

DZero is an international experiment of about 550 physicists from 90 institutions in 18 countries. It is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and a number of international funding agencies.

Fermilab is a national laboratory funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC.

InterAction Collaboration media contacts:

A full list of worldwide InterAction media contacts is available at: http://www.interactions.org/presscontacts/

For more information on the InterAction Collaboration, visit www.interactions.org.