The U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have teamed up with the DuPage County branch of the NAACP to support high school student researchers participating in the NAACP’s Afro-Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics, or ACT-SO. In July, six of these students went to the NAACP National Convention to showcase their scientific work.

ACT-SO provides students the opportunity to learn about and compete in various fields, including STEM, performing arts, humanities, visual arts, business and culinary arts. “Its main purpose is really to give students an opportunity to showcase their talents, explore areas that they might not have an opportunity to explore and to basically find out what they want to do when they get out of high school,” said Thomas Reed, the ACT-SO coordinator for the DuPage County Branch of the NAACP.

Eleven students participating in the ACT-SO program under the DuPage chapter of the NAACP qualified for the National ACT-SO competition. Photo: DuPage ACT-SO

This year, 26 students in the Chicagoland region produced original research in ACT-SO’s STEM category under the mentorship of experts from the two national labs and the University of Illinois Chicago. Argonne has provided mentors for this program for 10 years and Fermilab for the past three years.

“Actively participating in shaping the future of science is an integral part of our laboratory mission and our ultimate goal is to inspire the next generation of scientists,” said Victor Mateevitsi, an Argonne computer scientist and ACT-SO mentor. “The ACT-SO program enables us to collaborate closely with students, assisting them in realizing their innovative research ideas while providing them a real-world insight into the life of a scientist at a national laboratory.”

Six high school students — Jasmine Armstead, Bryan Mann, Daniel Mason, Paisley Namowicz, Chandler Brady and Amalachukwa Agwuncha — went to nationals, which brought together gold-medal-winning students from more than 200 counties across the United States.

Four of the students representing the DuPage County branch of the NAACP won the national competition, including Brady and Agwuncha.

“The whole goal for this partnership is really to fill the pipeline to get more diverse people into the sciences, into STEM in general. That’s one of the things we try to do with ACT-SO,” said Reed. “We’re focused on African-American students in this program, and we want to see them go all the way through college, grad school, then work in research labs throughout the U.S. and the globe or become professors.”

Onward to nationals

The students who went to the finals in Boston worked on a wide range of projects, including a thermal vest to help people with sickle cell anemia; the effect of psychological stress on blood pressure; predicting the magnitude of tornadoes; evaluating the viability of solar sails; monitoring air quality across built environments; and anesthetic drug discovery.

Armstead, a 12th grader at Plainfield East High School in Plainfield, Illinois, created a thermal vest to help people with sickle cell anemia in cold weather. “When your hands and feet tend to get cold first it’s because your blood vessels start constricting and blood goes back up to your core,” said Armstead. As she has sickle cell anemia, she could measure the effects of the vest for herself.

Namowicz, an 11th grader at Waubonsie Valley High School in Aurora, Illinois, worked on predicting the magnitude of tornadoes, using machine learning. She and her fellow students said they appreciated hearing from speakers from Fermilab, Argonne and other places as part of the ACT-SO program. “It really helped to inspire us as high school students to hopefully have similar outcomes like they did,” said Namowicz. “They were very inspirational and were able to help encourage us to lead similar paths.”

Agwuncha, a 10th grader at Proviso Mathematics and Science Academy in Forest Park, Illinois, worked on analyzing air-quality levels around Chicago. “The program uncovered one of my hidden strengths,” Agwuncha said. “I discovered that I delivered confident and concise oral presentations. Working with a scientist taught me valuable work ethic skills, such as communication and time management.”

Mann, a ninth grader at Waubonsie Valley High School, said that ACT-SO was “a very enjoyable experience that pays off in the end, and even if you don’t win, I think the experience is the most important thing, especially for my community that would be participating in it.” His project involved evaluating the viability of solar sails.

Mason, an 11th grader at Neuqua Valley High School in Naperville, Illinois, studied the effect of psychological stress on blood pressure using supercomputer simulations, which has never been done before. Mason said, “This program at ACT-SO has really helped me take my skills more seriously for science, allowing me to see for myself that I could actually have a passion for computer science, medicine or psychology.”

“Generally, the projects have some beneficial impact on society, whether it’s to the environment, medicine, improving accessibility to technologies or some other social impact,” said Marco Mambelli, a senior software developer at Fermilab and ACT-SO mentor. “It’s very nice to see how the students are interested in doing research and making a better world.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

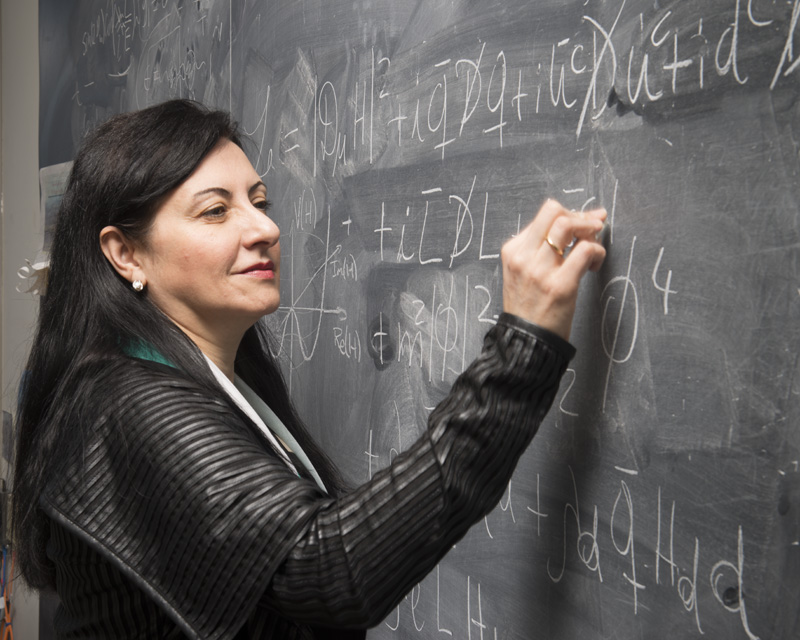

U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory scientist Marcela Carena has been recognized as one of Crain’s Chicago Business’ Notable Women in STEM for 2023 in the publication’s Sept. 4 issue.

Fermilab’s Marcela Carena was recognized in the Sept. 4 issue of Crain’s Chicago Business as a notable woman in STEM. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

Head of the Theory Division at Fermilab, Carena is a professor of physics at the University of Chicago, Enrico Fermi Institute, and the Kavli Institute of Cosmological Physics. In October 2022, she was one of two scientists to be named the 2022 Department of Energy Distinguished Scientist “for leadership and influential contributions to particle physics, including novel theoretical ideas and strategies for HEP experiments related to the Higgs boson, dark matter and electroweak baryogenesis, and promoting Latin American participation in DOE-hosted experiments.”

The Chicago-based business publication has honored industry and community leaders from Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Michigan; and New York since 2017. Honorees of Crain’s Notable Recognition Programs receive media exposure and exclusive LinkedIn community and networking events.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Editor’s note: Fermilab offers a wide range of STEM educational programs. This article is the first in a multi-part series that highlights some of the opportunities available at the lab.

For the first half of a weeklong workshop at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, a select group of high school teachers put on their “student hats” and learned how to use real-world scenarios to expose their students to particle physics.

They did so at the QuarkNet Data Camp. QuarkNet is a nationally acclaimed science education program, funded by the National Science Foundation and coordinated by the University of Notre Dame. Fermilab, a major contributor to the QuarkNet program since its inception, hosted the program’s annual Data Camp in July.

The camp lasts for a week and draws about two dozen high school teachers, predominantly physics teachers, from across the country. Other high school teachers who are teaching and learning fellows for QuarkNet run the Data Camp and instruct the participants. In addition to the main activities, the teachers participating in the workshop get to see Fermilab and learn from scientists.

For the first few days at the workshop, the teachers worked together in groups to analyze real particle collision data from the Compact Muon Solenoid detector at the Large Hadron Collider. The teachers must use the data — cleaned up a bit to make it easier to use — to figure out particle masses and look for a particular kind of particle collision event. Particles created in the collision decay into other particles, and by finding those post-decay particles, the teachers can infer what kind of event they are seeing.

“They were students for the first part of the week,” said Jodi Hansen, a high school physics teacher from Minnesota and a teaching and learning fellow for QuarkNet who has helped facilitate the program for more than a decade. “We pushed them; sometimes they were uncomfortable, and sometimes they were doing things that were hard for them. A lot of them hadn’t done physics like this before, and this is what physicists who work on the LHC do all the time.”

A group of teachers participating in the QuarkNet Data Camp presents what they have learned from their data set over the past few days. Photo: Spencer Pasero, Fermilab

Spencer Pasero, a member of Fermilab’s Office of Education and Public Engagement, said giving the teachers real datasets that physicists have used provides a more authentic experience, and it teaches them that real data can be messy and ambiguous. One challenge for the teachers is picking out signals, or useful information, from the background noise that clouds real-world data.

“You have to explore and figure out, ‘what’s this really telling me?’” he said. “Are there things that I might be assuming that are not accurate? How do you tell signal and background apart? In a lot of high school labs, there is no background, it’s all signal, and so being able to tease those things apart is useful.”

Putting the teachers into the position of student and asking them to solve problems can be daunting, said Jeremy Smith, Baltimore physics teacher and a teaching and learning fellow for QuarkNet who helps facilitate the data camp. But he and Pasero both said the process is rewarding and leaves the teachers eager to share what they have learned with their students.

“It can be really helpful to experience new topics, new content, new ways of thinking and working, from that student perspective,” Pasero said. “It helps them get into that mindset of, now that I’ve experienced this, and I know what I needed to learn to be able to understand this data, how am I going to give that to my students?”

Emily Rosen, a teacher from Cincinnati and a participant in this year’s data camp, has been teaching for 18 years and has been involved with QuarkNet since the beginning of her career.

For Rosen, analyzing the data challenged her in a way that teaching cannot. The experience gave her an opportunity to solve a complex physics problem and reminded her of what it’s like to be a student.

“As teachers of a subject that is sometimes intimidating and complex, it’s really good to be reminded that the first time a student sees something, it’s not as straightforward as it appears to me,” Rosen said. “It’s just nice to be academically challenged and to remind myself what that feels like, and what working with other people feels like when I’m feeling challenged.”

As the groups of teachers finished their project, they could then collaborate with and learn from other groups that were looking for particles with similar decay products. This collaboration helped the groups of teachers put together unique presentations that focus on the differences between the different groups’ tasks, Hansen said.

“They share with other teachers studying the same decay channel to see what their particle did to make those electrons, or to make those muons, that’s different with different particles,” she said. “We had them look for what was similar and what was different. When they got back together with their particle group, we asked them to point out things that were different from the other particles.”

This year’s QuarkNet Data Camp attendees stand before the reflecting pool in front of Fermilab’s Wilson Hall. Photo: Spencer Pasero, Fermilab

After the teachers gave presentations about what they learned, they spent the last couple of days discussing ways to use this experience to bring particle physics into their curriculum. In addition to the data camp, QuarkNet provides a vast library of data activities, covering different aspects of particle physics that teachers can integrate into their classrooms.

“For the second half of the workshop, they put their teacher hat back on and focus on thinking about ways that they can implement what they’ve learned into their curriculum,” Smith said.

“Teachers say they don’t have enough time to teach the stuff they already have to, to say nothing of an entire new unit,” he continued. “Rather, the teachers find it helpful to sprinkle these activities throughout the curriculum and do it as an addition to or replacement for something that they already have. They’re weaving particle physics concepts into the whole course.”

Hugo Delgado, a physics teacher from Puerto Rico, said he learned not only about particle physics and Fermilab, but also how fellow teachers use particle physics to construct a diverse and engaging physics curriculum.

Delgado usually works with other science teachers and doesn’t have many opportunities to meet fellow high school physics teachers. During the QuarkNet Data Camp, he got the chance to learn from peers.

“Learning that the difficulties I have as a teacher in Puerto Rico are similar to the ones that people from other places in the United States have, that gave me hope that I was doing things right,” Delgado said. “Also, they gave me ideas for how I can approach particle physics in my classroom.”

Discussing opportunities to bring particle physics into the classroom with other teachers was also inspiring to Rosen.

“Teaching science is like shooting a moving target — because if you’re doing it well, it’s changing — and we should keep up with it and bring it into our curriculum,” she said. “I am deeply appreciative of experiences where I can grow myself so that I can bring that back into my classes.”

QuarkNet Data Camp takes place each July. Teachers who are members of QuarkNet can be nominated by their mentor or QuarkNet staff to participate in the annual camp. There is no cost to attend – all expenses are paid – and the educators receive a stipend for their time.

“Even though it was just one week, I think it has been the highlight of the whole summer,” Delgado said. “I have already started to plan my year, and it’s going to have a great impact on how I approach my class this year.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.