Researchers at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory have successfully trapped and manipulated ions using in-vacuum cryoelectronics, allowing for reduced thermal noise and improved sensitivity. This proof-of-principle experiment marks an important advancement toward building large-scale ion-trap quantum computing systems.

The co-integration of ion traps and deep cryogenic control circuits project was made possible through collaboration between two DOE National Quantum Information Science Research Centers — the Quantum Science Center, led by Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and the Quantum Systems Accelerator, led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. This particular effort within the Quantum Systems Accelerator was led by Sandia National Laboratories in collaboration with MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

Recognizing the complementary expertise of Fermilab and MIT Lincoln Laboratory, leaders from both centers jointly supported the demonstration.

“This remarkable research integrates state-of-the-art capabilities in quantum technologies to deliver an exciting new direction for scalable ion trap quantum computing using cryoelectronic control chips,” said Travis Humble, director of the Quantum Science Center.

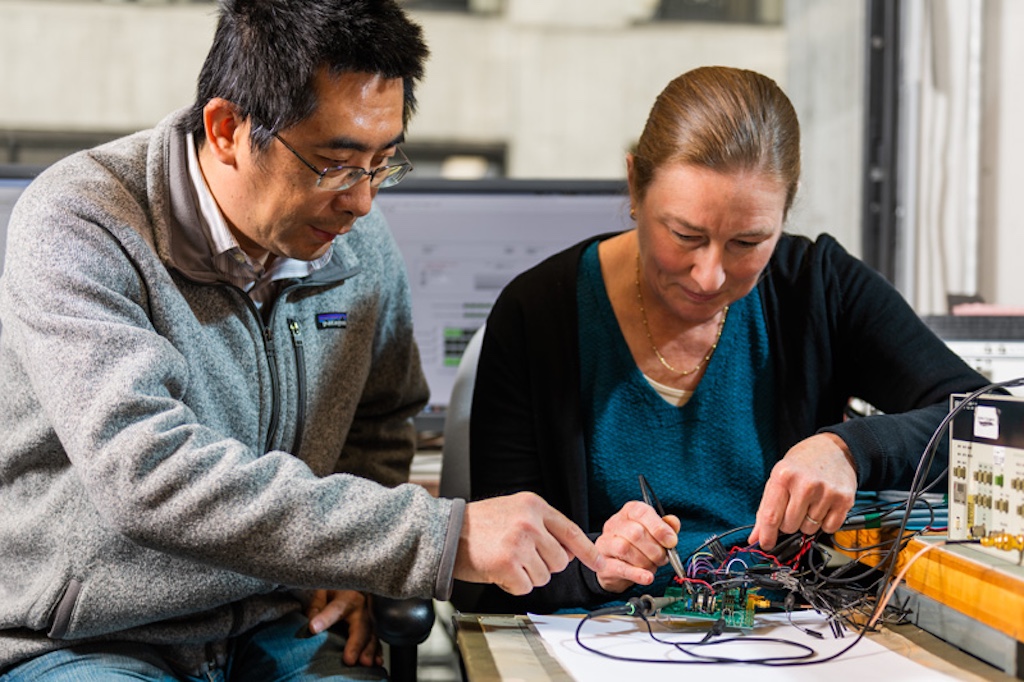

At the heart of the effort were Fermilab-developed cryoelectronics — specialized circuits designed to operate at the extreme cold temperatures required for quantum computers. These cryoelectronics were integrated into MIT Lincoln Laboratory’s ion-trap platform to test whether they could reliably perform key functions: moving individual ions, holding them at set positions and measuring the effects of electronic noise.

Why ion traps?

Ion-trap quantum computers use charged atoms confined by electric or magnetic fields as qubits. Such systems are prized for their long coherence times and high-fidelity operations.

However, scaling them to millions of qubits, as needed for advanced applications, is a major challenge. Today’s systems rely on lasers and extensive wiring between room-temperature electronics and cryogenic ion traps — a setup that becomes increasingly impractical as the number of ions grows.

By placing ultra-low-power cryoelectronics near the ion traps, the Fermilab–MIT Lincoln Laboratory team realized a promising path forward. Their redesigned system replaced some of the room-temperature controls with a chip mounted inside the cryogenic environment. The researchers successfully demonstrated this hybrid approach could move and control ions.

“In addition to demonstrating feasibility, we learned a lot,” said Farah Fahim, head of Fermilab’s Microelectronics Division. “By showing that low-power cryoelectronics can work inside ion-trap systems, we may be able to accelerate the timeline for scaling quantum computers, bringing closer into reach what seemed decades away. This approach could ultimately support systems with tens of thousands of electrodes or more.”

Future work will directly connect the electronics with the ion-trap chips, further increasing efficiency and performance and enabling scaling of ion-trap arrays for larger systems.

Lessons learned

The experiment also surfaced new insights that will guide future chip designs. For instance, transistors that behaved well in Fermilab’s setup did not perform as well in MIT Lincoln Laboratory’s significantly colder environment, impacting the control circuit performance and operation range.

Also, the circuits initially held voltages for milliseconds. Though modifications extended the hold times, further modifications will be required to further extend them to the minutes or hours large systems require. Addressing these and other challenges will be central to the next round of development.

Robert McConnell, a technical staff member at MIT Lincoln Laboratory, said that “while there are still significant challenges to establishing the technology needed to control ion arrays of a practical scale, this demonstration of small-form-factor, low-noise electronics lays the foundation for hybrid-integrated systems we hope to develop in the near future.”

The successful integration highlights the value of cross-center collaboration, in addition to marking a concrete step toward realizing scalable quantum computing technologies for science and beyond.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

The Quantum Systems Accelerator (QSA) is a U.S. National Quantum Information Science Research Center established in August 2020 and funded by the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. QSA is composed of 15 partner institutions—universities and national laboratories—bringing together pioneers of many of today’s unique quantum information science (QIS) and engineering capabilities. Led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), with Sandia National Laboratories (Sandia Labs) as the lead partner, 250+ QSA researchers are catalyzing U.S. leadership in a fast-growing field that seeks solutions to the Nation’s and the world’s most pressing problems by harnessing the laws of

quantum information science.

Headquartered at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the Quantum Science Center (QSC) is one of five multidisciplinary National Quantum Information Science Research Centers supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. Initially created in 2020 and renewed in 2025 in response to the National Quantum Initiative Act of 2018, the QSC is focused on advancing quantum information science and technology in the interests of national security and global scientific leadership.

MIT Lincoln Laboratory is a federally funded research and development center sponsored by the Department of Defense. FFRDCs assist the U.S. government with scientific research and analysis, systems development, and systems acquisition to provide novel, cost-effective solutions to complex government problems. MIT Lincoln Laboratory researches and develops a broad array of advanced technologies to meet critical national security needs.

Editor’s note: The following press release was posted by CERN on February 23, 2026.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory developed and shipped five cryoassemblies containing niobium-tin magnets for use in the High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider upgrade at CERN. The newly developed and tested magnets will focus the beam at the CMS and ATLAS interaction points, increasing the number of collisions for the experiments tenfold in the HiLumi era.

Fermilab will deliver five additional cryoassemblies by mid-2027. The innovative magnet system is an important element in the major upgrade that will transform the Large Hadron Collider into the HiLumi LHC. Fermilab’s leadership and participation in the upgrade demonstrate the lab’s commitment to its ongoing collaboration with CERN and other Department of Energy national laboratories.

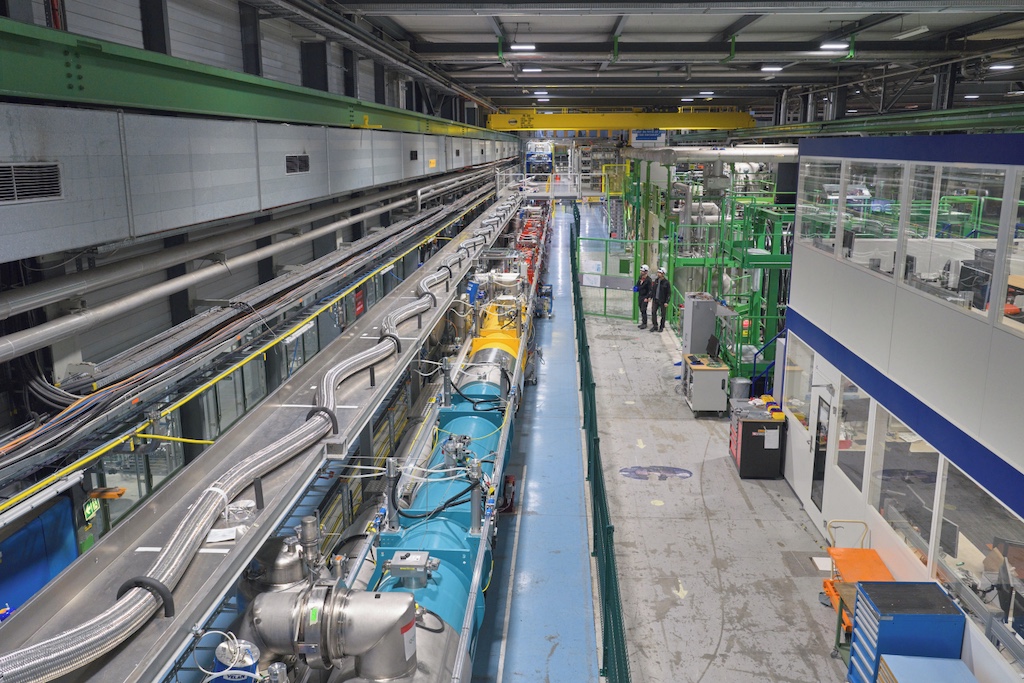

CERN has reached a crucial milestone in the advancement of the High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HiLumi LHC) project with the start of the cryogenic cooldown to 1.9 K (-271.3 °C) of its 95-metre-long test stand – a full-scale replica of the innovative equipment that will transform the LHC in the coming years. The test stand is designed to validate the novel magnet system (the inner triplet beam-focusing magnets) and its complex infrastructure, which is a key element in a major upgrade of the LHC that is set to enter operation in 2030.

This summer will mark the start of a four-year-long intensive work period (Long Shutdown 3 – LS3) to transform the LHC into the HiLumi LHC—a groundbreaking accelerator that will usher in a new era for high-energy physics. The HiLumi LHC will increase by a factor of ten the number of particle collisions (called “luminosity”), vastly increasing the volume of physics data available for researchers. This leap forward will allow physicists to explore the behaviour of the Higgs boson and other elementary particles with unprecedented precision and to uncover rare new phenomena that might reveal themselves.

“I don’t think it is possible to overstate the importance and excitement of the High-Luminosity LHC, which is the largest project undertaken by CERN for the past 20 years,” explains Mark Thomson, CERN Director-General. “Coupled with advanced new data tools and upgraded detectors, it will allow us to understand for the first time how the Higgs boson interacts with itself – a key measurement that will shed light on the first instants and possible fate of the Universe. The HiLumi LHC will also explore uncharted territory and could reveal something completely new and unexpected. That’s the whole point of exploring the unknown: you don’t know what’s out there.”

Many of the technologies developed for the HiLumi LHC – such as superconducting crab cavities that tilt the particle beams before they collide, crystal collimators designed to remove errant particles, and high-temperature superconducting electrical transfer lines to power the HiLumi magnets as efficiently as possible – have never been used in a proton accelerator before. Among these new key technologies, the inner triplet beam-focusing magnets are made of a superconducting compound based on niobium and tin (Nb3Sn), enabling magnetic fields higher than those achieved with the current LHC niobium–titanium (NbTi) magnets. These new magnets will be deployed on both sides of the ATLAS and CMS experiments, alongside new cryogenic, powering, protection and alignment systems, and will operate at a temperature of 1.9 K (-271.3 °C), just like the LHC magnets.

To ensure seamless integration, CERN has built, in an above-ground test hall, a full-scale test stand called the Inner Triplet String (IT String), which mirrors the underground configuration.

“All the systems have already been tested individually. The goal of the IT String is to validate their integration and their collective performance under operational conditions,” explains Oliver Brüning, CERN Director for Accelerators and Technology. “The connection and operation of all the equipment in the IT String give us a chance to optimise our procedures before the actual installation in the tunnel, so that we will be prepared and ready for an efficient and smooth installation.”

The large LHC experiments ATLAS and CMS will also undergo a major upgrade to enable them to harness the full scientific potential of the HiLumi LHC collisions – work that is being carried out in close coordination with hundreds of institutes worldwide. Additionally, the entire accelerator complex and associated experiments will benefit from improvements, solidifying CERN’s leadership in high-energy physics.

The HiLumi LHC project is led by CERN with the support of an international collaboration of almost 50 institutes in more than 20 countries – the vast majority located in Europe. In addition to the funding provided by CERN Member States and Associate Member States, the project received special contributions from Italy, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Serbia and Pakistan, and from several non-Member States such as the United States, Japan, Canada and China.

The cooldown of the HiLumi LHC test string, which is achieved using a sophisticated liquid- helium refrigeration and distribution system, is expected to take several weeks to complete.

Anadi Canepa, a senior scientist at Fermilab, has begun work as the new spokesperson of the CMS collaboration. Having served as the deputy spokesperson since 2024, she takes over from Gautier Hamel de Monchenault, becoming the latest leader of the approximately 6,000-member international collaboration at the forefront of particle physics at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.

Canepa brings a distinguished record of scientific leadership and technical expertise to the role. Her career spans more than two decades across three major collider experiments: CDF, ATLAS and CMS.

The CMS experiment is one of the two general-purpose detectors at the LHC, designed to explore a wide range of physics phenomena — from the Higgs boson to searches for new particles and forces.

Canepa’s selection comes at a pivotal moment for CMS, as the collaboration prepares for the High-Luminosity LHC, which will increase the particle collision rate by a factor up to five.

As the LHC enters this next chapter, CMS will undergo major transformations. The Phase-2 upgrade, currently underway, includes a complete overhaul of key detector systems.

These enhancements will enable CMS to maintain its precision and performance while unlocking new opportunities for discovery and a deeper understanding of the fundamental structure of the universe.

“I’m honored to serve this high-caliber collaboration as we bring the LHC program to fruition and upgrade the CMS detector for the HL-LHC era,” said Canepa. “CMS at the HL-LHC will push the boundaries of our understanding of matter and energy.”

Since joining CMS in 2015, Canepa has led several critical efforts, including the coordination of beam and system tests for the Outer Tracker and management of the U.S. electronics project for the HL-LHC upgrade. She served as head of the Fermilab CMS department for six years and held strategic roles at the lab, including director of Users Facilities and Experiments and scientific secretary of the Fermilab Physics Advisory Committee. In 2025, she was also named an American Physical Society Fellow.

“Her deep expertise and unwavering commitment to collaboration will be essential as CMS enters a transformative era with the High-Luminosity LHC.”

Director of Fermilab Norbert Holtkamp

Her research focuses on Higgs physics, searches for physics beyond the Standard Model, and the development of advanced trigger and tracking systems. She has authored numerous influential publications and has served on international committees, including as chair of the Division of Particles and Fields of the Canadian Physical Society.

“I extend my sincere congratulations to Anadi Canepa on her selection for this important leadership role with CMS,” said Norbert Holtkamp, director of Fermilab. “Her deep expertise and unwavering commitment to collaboration will be essential as CMS enters a transformative era with the High-Luminosity LHC.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.