On March 6, the University of Campinas in Brazil, known as UNICAMP, and the Department of Energy’s Fermilab signed an agreement to collaborate on R&D for the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility, the infrastructure supporting the international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, hosted by Fermilab. On the same date, representatives from the São Paulo Research Foundation, known as FAPESP, and Fermilab signed a memorandum of understanding on scientific cooperation in high-energy physics.

“The University of Campinas is very proud of this important agreement with Fermilab, which will be a major enrichment in a long-term relationship in basic research, specifically neutrino physics. We look forward to helping build this world-class facility and addressing the significant engineering challenges it presents, and we strongly believe that together we will contribute to the advance of science and technology,” said University of Campinas Rector and Professor Marcelo Knobel.

“FAPESP values highly the collaboration with Fermilab,” said FAPESP Science Director Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz. “This agreement will open opportunities for young researchers of any nationality to start their careers in science in universities in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, working in advanced topics related to experimental neutrino physics in the DUNE experiment.”

The Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, known as DUNE, will study neutrinos sent from Fermilab, outside Chicago, to Lead, South Dakota, 1,300 kilometers away. There, in caverns 1.5 kilometers beneath the surface, an underground particle detector filled with 70,000 tons of liquid argon will capture the interactions of some of these neutrinos, providing scientists with hints about the evolution of our universe.

From left: FAPESP Adjunct Coordinator for Special Programs and Research Collaborations Luiz Nunes de Oliveira, Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer, University of Campinas Rector Marcelo Knobel, Brazil Minister of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communication Marcos Pontes, U.S. Undersecretary of Commerce of Standards and Technology and NIST Director Walter Copan. Photo: Brazil Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communication

The Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility, or LBNF, will provide the cryostats housing the DUNE detector and the cryogenics to maintain the temperature of minus 184 degrees Celsius for the liquid argon inside the giant detector. The cryogenics include the nitrogen refrigeration system, pipes, pumps and other equipment needed to fill the cryostats, keep them cold, and circulate as well as purify the liquid argon.

UNICAMP researchers are contributing to LBNF/DUNE by conducting studies and tests related to recirculating, purifying, regenerating and condensing argon, including prototyping of the construction, to ensure that the necessary components meet specifications. The collaborators may also engineer, design, manufacture, test, ship and deliver systems for purifying, regenerating, circulating and condensing the argon.

“The University of Campinas continues to expand its research program with Fermilab, building on its highly successful photon detection system, called Arapuca, for DUNE. The São Paulo region brings state-of-the-art engineering talent and know-how to contribute to our challenging cryogenic designs. The FAPESP funding agency, led by Dr. Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, has been a wonderful partner in building our relationship with the entire Latin American science and engineering community,” said Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer.

The memorandum of understanding promotes and deepens scientific and technological cooperation between researchers from the Brazilian state of São Paulo and Fermilab in the areas of high-energy physics, including neutrino research.

U.S. research on LBNF/DUNE is supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

The Accelerator Neutrino Neutron Interaction Experiment at Fermilab, known as ANNIE, has seen its first neutrino events. This milestone heralds the start of an ambitious program in neutrino physics and detector technology development. It is also a cause for celebration by the international ANNIE collaboration, composed of groups from Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, who have been working diligently over the last two years to design and build the experiment.

ANNIE has a list of “firsts” it plans to achieve: (1) the first accelerator experiment to use water doped with gadolinium to efficiently tag neutrons and (2) the first experiment to use new light-detection technology that can track particles with precision better than 100 trillionths of a second.

The new sensors, called large-area picosecond photodetectors, or LAPPDs, were initially developed for particle physics, supported by funding from the Department of Energy’s Office of Science. Since then their development has also sparked interest in their use as a new commercial technology in a wide variety of fields, ranging from medicine to aerospace. ANNIE scientists hope that the use of these photodetectors will allow them to track neutrino events with unprecedented precision in an optical light detector, which would be a major advance in neutrino detector technology.

ANNIE will also be able to try out other new technologies during its planned two-year run, including water-based liquid scintillator and wavelength-sensitive photodetectors, which are also being considered for next-generation experiments. Indeed, the trial of new technologies by ANNIE is expected to have an impact on the design of future neutrino detectors in general.

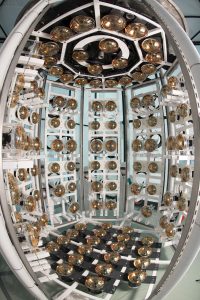

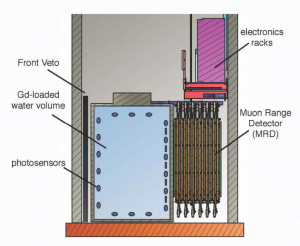

The ANNIE detector sits in a 30-meter-deep underground hall on the Fermilab site (see illustration below). In the ANNIE design, neutrinos enter from the left and pass through the front veto, which rejects charged particles from neutrino events generated upstream. They then interact in the water volume to create an energetic muon (and possibly other charged particles). These charged particles make a characteristic Cherenkov light flash that is detected by the photosensors that line the wall, top, and bottom of the cylindrical water tank, which is about 3 meters in diameter and 4 meters high. This flash gives information on the neutrino interaction energy and also provides information on the muon direction — critical information for understanding the interaction. If the muon penetrates the full water volume it can enter the muon range detector, which tracks the muon and measures the energy deposited in the iron sandwich.

The ANNIE detector sits in an underground hall at Fermilab. The neutrino beam impinges from the left. The detector consists of three main elements: (1) a front veto to reject charged particles from neutrino events occurring upstream of the hall in the dirt, (2) an instrumented tank containing 25 tons of gadolinium loaded water to serve as both the neutrino target and neutron tagger, and (3) an iron and scintillator sandwich muon range detector to track and range out muons from the neutrino interactions in the target. Image: ANNIE collaboration

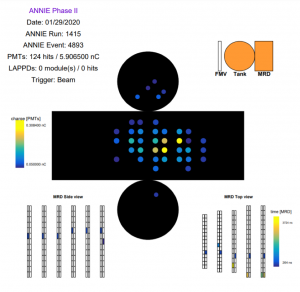

The ANNIE detector is currently being commissioned, and in January, it obtained its first neutrino events. In the image shown below, the cylindrical tank containing the doped water and array of photosensors — instruments that detect the neutrino interaction signal — is unfolded such that the sides of the tank appear as a large rectangle, while the circular top and bottom arrays are shown as circles. Each filled color circle represents a photosensor that was hit by Cherenkov light in time with the arrival of the pulsed neutrino beam, with the color scheme proportional to the amount of light (yellow is a high light level, purple is a low light level). The splash of light signals a muon from a neutrino interaction exiting the target volume. After the muon exited the tank it entered the muon range detector, where its track can be seen in the scintillator detectors in both the top and side views. The spaces between the scintillator detectors are filled with 2 inches of iron, and in this case, the muon was able to penetrate all the layers and exit the detector.

This process takes only a few microseconds. The interesting and unique thing about ANNIE is what happens next. Neutrons can be created by the initial neutrino interaction. They can also be created by nuclear interactions in the struck oxygen nucleus (in the water) in a process that is not completely understood. These neutrons slow down and are captured on the gadolinium in the water tank over a much longer time period than the initial interaction (about 80 microseconds), allowing ANNIE to count the number of neutrons as a function of various neutrino interaction parameters to compare to model predictions. Currently, the gadolinium doping of the water is complete, and ANNIE is commissioning this unique part of its sensitivity with artificial-neutron-source deployments. ANNIE scientists expect to start efficiently detecting neutrons in coincidence with neutrino interactions very soon.

The cylindrical tank containing the doped water and photomultiplier tube array is shown unfolded: The sides of the tank appear as a large rectangle, and the circular top and bottom arrays are shown as circles. Each filled color circle represents a photosensor that was hit by Cherenkov light in time with a neutrino beam, with the color scheme proportional to the amount of light (yellow is a high light level, purple is a low light level). Image: ANNIE collaboration

ANNIE’s pioneering accelerator neutrino measurements will contribute to understanding upcoming data from the Super-Kamiokande experiment in Japan, which is planning to add gadolinium to its water this spring. This is an excellent example of international scientific cooperation: the work done by the Super-Kamiokande collaboration in advance of their own gadolinium loading helped guide the design of ANNIE at Fermilab.

This first observation of neutrinos in the ANNIE detector is expected to be followed by several thousands more over the next two years. Results from ANNIE will help physicists understand the role of nuclear effects in neutrino interactions – a topic that is also of critical interest to the international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, hosted by Fermilab.

Congratulations to the ANNIE collaboration on reaching this first critical milestone!

Bob Svoboda is a University of California, Davis, professor of physics and member of the ANNIE collaboration.

U.S. support for the ANNIE collaboration is provided by DOE’s Office of Science and National Nuclear Security Administration. UK support is provided by UK Research & Innovation.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.