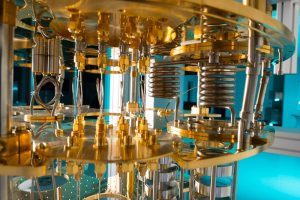

Fermilab is one of the core institutions that form the Chicago Quantum Exchange. The organization is hosting the Chicago Quantum Summit on Nov. 8-9. Photo: Reidar Hahn

On Nov. 8-9, Fermilab scientists will discuss their research in a gathering organized by the Chicago Quantum Exchange to explore the revolutionary potential of quantum science. At the Chicago Quantum Summit, held at the University of Chicago, members of both the public and private sector will look for ways they can work together to produce game-changing technologies for science and society, such as unhackable information networks and ultrafast computers.

The summit will bring experts together from the Department of Energy, the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the National Science Foundation, Alphabet Inc.’s Google, IBM, Microsoft, national laboratories, universities and other companies and organizations.

One of the core institutions that form the CQE, the Department of Energy’s Fermilab is drawing on its world-class expertise in physics and computing to develop boundary-pushing technologies based on quantum phenomena. Fermilab Chief Research Officer Joe Lykken, one of the summit’s speakers, will highlight Fermilab’s capabilities at a panel discussion on the national labs’ role in quantum science. The lab will also showcase its quantum initiatives in a scientific poster session.

One of these initiatives is the eventual construction of a quantum teleportation network, to be developed by Fermilab and Argonne National Laboratory in partnership with the University of Chicago, as well as with Caltech/Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Harvard University, MIT and private companies. The network, to stretch between Argonne and Fermilab, exploits a principle called quantum entanglement, in which two or more particles are inextricably linked to each other. If scientists share an entangled pair of particles between two locations, the encoded information is protected from third-party access, no matter the distance — it is “teleported.”

Fermilab is also adapting cutting-edge technology to improve the length of time that qubits — quantum computing bits — are stable. Using structures that are typically used to accelerate subatomic particles, Fermilab scientist Alex Romanenko is working on increasing the length of time that a qubit can sustain operation, which could lead to more powerful quantum computers.

Qubit technology can also be applied in the search for dark matter. Fermilab scientists Aaron Chou and Daniel Bowring are using it to detect tiny signals generated by a hypothesized type of dark matter known as the axion particle. Sensitive to the presence of just a single particle, a qubit can detect the subtle presence of axions, which, if they exist, would make themselves known by generating solo particles of light, otherwise known as single photons.

And there are the applications of quantum science to particle physics more broadly: Fermilab researchers are advancing quantum simulations and algorithms to crack intractable problems of the field and to facilitate the analysis of massive amounts of particle physics data.

The summit also features a free public event. On Thursday, Nov. 8, at 6 p.m., CQE will host “Quantum Engineering: The Next Technological Space Race,” which includes a keynote talk by Hartmut Neven, Google’s director of engineering for artificial intelligence and quantum. The public can also listen to a conversation between Neven and David Awschalom, the University of Chicago’s CQE director. Please note that registration is required.

The Chicago Quantum Exchange’s core institutions are Fermilab, Argonne National Laboratory, the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

More information on Fermilab’s quantum science can be found at http://qis.fnal.gov. Fermilab’s quantum science initiatives are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.