On Nov. 21, DOE Undersecretary for Science Paul Dabbar visited Fermilab and took a tour of the laboratory. Dabbar serves as the science and technology advisor to Energy Secretary Rick Perry and, as part of his portfolio, oversees the Office of Science and its national labs. Dabbar was previously the managing director for mergers and acquisitions at J.P. Morgan & Co. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and Columbia University, he served as a nuclear submarine officer aboard the USS Pintado.

During his visit, Dabbar met with the Fermilab management team, local Congressman Randy Hultgren, members of the DOE Fermi Site Office, and about 20 scientists, including seven recipients of Presidential and DOE Early Career awards. Discussion covered the lab’s mission and projects, including the international LBNF/DUNE project and the broad international participation in the project.

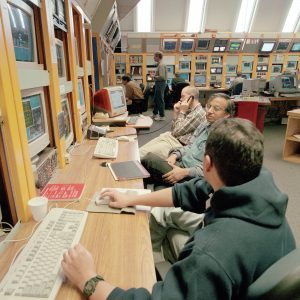

This is what the Main Control Room was like in the 2000s. But when there was an unscheduled power outage, what did these industrious folks do? Photo: Fred Ullrich

Sometime in the early 2000s, I remember, we had an unscheduled power outage. I had gotten a call at home at about 11 p.m. from someone in the Main Control Room to come in to restart my equipment since power restoration was imminent. So I made the 45-minute drive to the lab and made the right-hand turn from Pine Street toward the high-rise building (which is near the Main Control Room) just in time to see all the lights go off again. I had decided that under the circumstances, it was better for me to stick around the Main Control Room and wait for word from the power company or the people in the lab’s High Voltage Group than to make the drive back home just to turn around and come back at any moment.

Well, our group waited … and waited. We had already configured our equipment into a safe mode for when the power returned. There was nothing to do but immerse ourselves in all the line drawings sprawled out on the Crew Chief desk and debate what had happened. Nobody knew if the problem could be fixed quickly or if there was going to be an extended power outage. It would turn out to be a long wait into the morning.

Then, at about 8 a.m., I heard some commotion outside, so I decided to go see what was happening. Outside, in the Main Control Room parking lot, there was a pickup truck, and in the back of the truck was an 8-kilowatt generator. About four or five people were gathered around this generator. One person was pulling and pulling on the generator rope trying to get it started. Another one stepped in and took out the needle valve for inspection. Somebody else grabbed a hammer and started tapping on the float bowl of the carburetor. Try as they may, they just couldn’t get the engine started. Next the spark plug came out. They were all feverishly working on this generator with urgency as if it were an emergency.

I felt a sense of dedication and devotion to the lab seeing all these people pitching in to help get this generator started. I was still very new at the lab, so seeing all this teamwork made a very good impression on me. But I wondered, what was all the fuss about? What could they possibly be trying to power up after the power being off for 10 hours? The computer room? A sump pump? Was is something necessary to prevent disaster?

So I followed the huge industrial sized extension cord from the parking lot, through the doorway, and into the kitchen next to the Main Control Room, where it was plugged into a coffee pot.

The following statement was issued today by the International Committee for Future Accelerators, a 16-member body created in 1976 to facilitate international collaboration in the construction and use of accelerators for high energy physics. Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer is a member and past chairperson of ICFA. ICFA’s full press release is available at Interactions.org.

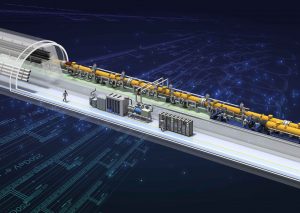

ICFA statement on the ILC operating at 250 GeV as a Higgs boson factory

The discovery of a Higgs boson in 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN is one of the most significant recent breakthroughs in science and marks a major step forward in fundamental physics. Precision studies of the Higgs boson will further deepen our understanding of the most fundamental laws of matter and its interactions.

The International Linear Collider (ILC) operating at 250 GeV center-of-mass energy will provide excellent science from precision studies of the Higgs boson. Therefore, ICFA considers the ILC a key science project complementary to the LHC and its upgrade.

ICFA welcomes the efforts by the Linear Collider Collaboration on cost reductions for the ILC, which indicate that up to 40 percent cost reduction relative to the 2013 Technical Design Report (500 GeV ILC) is possible for a 250-GeV collider.

ICFA emphasizes the extendability of the ILC to higher energies and notes that there is large discovery potential with important additional measurements accessible at energies beyond 250 GeV.

ICFA thus supports the conclusions of the Linear Collider Board (LCB) in their report presented at this meeting and very strongly encourages Japan to realize the ILC in a timely fashion as a Higgs boson factory with a center-of-mass energy of 250 GeV as an international project1, led by Japanese initiative.

In the LCB report, the European XFEL and FAIR are mentioned as recent examples for international projects.