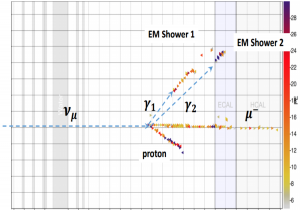

In this plot, a neutrino enters from the left, interacting with a nucleus in the MINERvA detector material. The interaction results in two photons, a negatively charged muon that exits the end of the detector on the right, and a proton. This process can give neutrino oscillation experiments such as Fermilab’s NOvA and DUNE insight into two mysteries that they must solve. It is critical to determine two things about each neutrino that leaves a trace in the detector: its flavor and its energy.

Para una versión en español, haga clic aquí. Para a versão em português, clique aqui.

Neutral-pion production is a major character in a story of mistaken identity worthy of an Agatha Christie novel.

First, the cast of characters: Neutrinos, the quarries of the MINERvA experiment, are subtle, difficult-to-capture particles. They come in three types, two of which play a prominent role in this story: the electron neutrino and the muon neutrino. Since neutrinos are hard to capture, scientists do the next best thing: study other types of particles resulting from the neutrino’s interaction with a nucleus in the detector.

One of these resulting particles is the pion. Pions can be electrically neutral or not. In this story, we focus on neutral pions, and they often transform into two photons, particles of light.

Then there’s the electron, a particle we all know and love, and its cousin the muon. An electron neutrino leaves behind electrons, and a muon neutrino leaves behind muons.

Finally, a twist: neutrinos can switch identities. An electron neutrino can flip and become a muon neutrino and vice versa. The behavior is called oscillation.

Oscillation experiments look for electron neutrinos (which leave electrons in their wake) that were originally muon neutrinos (which produce mostly muons). If they see an electron, they know their muon neutrino has oscillated into an electron neutrino. If they see a muon, they conclude the muon neutrino did not oscillate by the time it reached them.

Every good mystery has its red herrings, and in this case of mistaken identity, the culprit is the pion: Neutral pions can disguise themselves as electrons —the telltale sign that an electron neutrino has passed through — in a particle detector. So when scientists think they have identified electrons, they might actually be looking at pions.

Why does this happen? Pions decay into two photons. Let’s say that one photon escapes detection, and the other, as often happens, looks a lot like an electron. This can trick the experiment into counting what was really the arrival of two photons as an electron sighting —therefore counting an event as the arrival of an electron neutrino when it was really a muon neutrino. So it seem like the neutrino has oscillated when, really, it has not.

To avoid such misidentification, MINERvA scientists measured how often a neutrino interaction results in a muon and a neutral pion. This measurement gives us one handle on predicting the number of cases of mistaken identity that bigger Fermilab neutrino experiments, namely NOvA and DUNE, will see.

Measuring neutral-pion production can also help us understand the relationship between the neutrino’s energy and the resulting particles we see in our detectors. One of the biggest problems in oscillation experiments occurs when a neutrino of one energy masquerades as a neutrino of another energy. This happens frequently when some of the particles get stuck inside the nucleus of the detector material or transform into other particles. MINERvA’s measurement of neutral-pion production is sensitive to these kinds of effects and helps theorists improve their models of the nucleus.

The MINERvA collaboration is excited about these new results. The protons in our detector are also excited — they reach very high energy levels in the neutrino events studied in this analysis.

For the first time ever, we have a measurement where both a neutral pion and a proton are observed. These pion-proton events tell us about the behavior of a kind of excitation that occurs inside the nucleus. These measurements also contain information about the energy and angles of both the neutral pion and the muon that goes with it.

This level of detail is important both for oscillation experiments and for improving our theoretical models.

The MINERvA collaboration recently submitted for publication a paper on measurements of neutral pion production by neutrinos. This result was presented at the Fermilab wine and cheese seminar on July 7 by Ozgur Altinok of Tufts University, an analysis he performed along with Trung Le, also of Tufts.

Barbara Yaeggy is a physicist at Federico Santa María Technical University in Chile.

This article was translated from the Spanish by physicist Chris Marshall of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

In September, lab employees move to Weston, Colorado bison move to Illinois, and Nigel Lockyer moves to the United States. Read on for more September historical milestones.

In September 1969, the first bison arrived on the lab site. The first six animals were purchased by the lab from a herd in Colorado, and the next year a larger group arrived from a herd in Illinois. The bison were part of Director Robert R. Wilson’s vision of the lab as a physical and intellectual frontier and contributed to his goal of restoring some of the the native ecosystems of the area.

Nigel Lockyer became Fermilab’s sixth director on Sept. 3, 2013. Lockyer spent 22 years as a researcher on Fermilab’s CDF experiment and served as the co-spokesperson from 2002 to 2004. He also won the 2006 W.K.H. Panofsky Prize. When he became Fermilab’s director, he was director of Canada’s TRIUMF Laboratory.

Director Robert Wilson is sometimes known as the “father of proton therapy” for his 1946 paper “Radiological Use of Fast Protons,” which first suggested the idea of using protons for medical treatment. Wilson helped organize Fermilab’s Cancer Therapy Facility, as it was originally known, using funding from the National Cancer Institute and beam from Fermilab’s Linac. The Neutron Therapy Facility treated its first patient on Sept. 7, 1976. In 1989, Fermilab would design and build a proton accelerator for Loma Linda University Medical Center in California, the first hospital-based proton treatment center.

Fermilab is a member of the Dark Energy Survey, an international collaboration formed in 2003 that uses a camera mounted on the Blanco Telescope in Chile to study the effects of dark energy. On Sept. 12, the Dark Energy Survey’s Dark Energy Camera received first light.

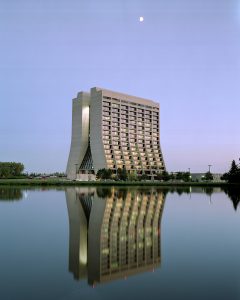

Shortly after Fermilab’s first director, Robert R. Wilson, retired, the lab renamed the Central Laboratory Building to Wilson Hall in his honor.

NAL employees started moving to the Weston site during the summer of 1968 and completed the move at the end of September.

Fermilab’s Lederman Science Education Center was named in honor of the lab’s second director, Leon Lederman, in recognition of his work to improve science education.

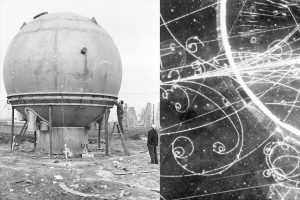

Bubble chambers detect particles by recording tracks of bubbles the particles leave in liquid, and Fermilab was home to the largest liquid-hydrogen bubble chamber in the world. The 15-Foot Bubble Chamber photographed its first particle trails on Sept. 29, 1973. It would record its last tracks on Feb. 1, 1988.