As we enter the second month of Fermilab’s 50th year, we look back on Robert Wilson assuming the lab’s first directorship and the lab’s first experiment, along with other memorable milestones.

Feb. 5, 1999: Evidence of CP violation in neutral B mesons

On this day, CDF scientists reported evidence of CP violation in neutral B mesons — a phenomenon that could help explain why matter predominates in our universe while antimatter is nearly absent.

Feb. 12, 1972: First experiment

Experiment E-36, Small Angle Proton-Proton Scattering, began testing equipment in the lab’s newly achieved 100-GeV beam in the Internal Target Area on this day, marking the beginning of the lab’s experimental program. The E-36 experimenters came from the National Accelerator Laboratory, the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (Dubna, U.S.S.R.), the University of Rochester (Rochester, New York) and Rockefeller University (New York City), making it a model of cooperation between Americans and Soviets at a time when Cold War tensions still ran high.

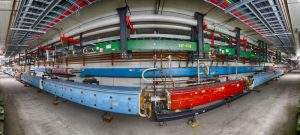

The DZero detector is visible at the far end of the hall behind the flags. The blue tower is the mobile counting house where all the cables from the detector are routed to. Both moved in unison with each other. Once the detector was in place, a concrete blocks were stacked to cover opening, providing shielding. Some of the blocks are visible on either side of the detector.

Feb. 14, 1992: DZero detector placed in Tevatron

Named for the section of the Tevatron ring where it was installed, the DZero detector was rolled into place on this day. By this day, the DZero scientific collaboration had grown to about 300 members. First collisions were seen three months later, and the experiment began taking data in September 1992.

Feb. 15, 1984: Tevatron achieves proton beam energy of 800 GeV

With the achievement of an 800-GeV operating beam energy, on this day the Tevatron regained the lead as the highest-energy fixed-target laboratory in the world. An 800-GeV ramp was set up in the Tevatron and achieved by 6:30 p.m. The Tevatron then accelerated and extracted beam to 800 GeV by 10:54 p.m. The beam marked the opening of a new energy frontier in high-energy physics.

Feb. 28, 1967: Robert Wilson becomes lab director

On Feb. 28, 1967, Robert R. Wilson, director of the Laboratory for Nuclear Studies at Cornell University, agreed to direct the planned National Accelerator Laboratory. Wilson was born in Frontier, Wyoming, and spent time on his family’s cattle ranch as a child. He also immersed himself in books from his local library and experimented in his mother’s attic, a background which nurtured his independence and his love of the challenge of the frontier. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, and became the youngest group leader on the Manhattan Project. He was also an avid sculptor, and his artistic sensibilities would shape Fermilab’s unique aesthetic. In 1987, on the occasion of the lab’s 20th anniversary, he would write that his “fantasy of a utopian laboratory clearly required a setting of environmental beauty, of architectural grandeur, of cultural splendor.”

Roger Dixon and Erik Ramberg (third and fourth from left) have directed Fermilab’s successful Saturday Morning Physics for more than 20 years. Now they pass the torch to Elliott McCrory (far left) and Sowjanya Gollapinni (not pictured). Suzanne Weber (second from left) has been a pillar of the program, serving as coordinator since 1990. Photo: Dan Garisto

Over the past 37 years, local students have spent their Saturday mornings not in front of a TV watching cartoons, but in front of a blackboard, learning physics.

Since its inception in 1980 by then-Fermilab Director Leon Lederman, Saturday Morning Physics has been one of the most popular outreach initiatives at Fermilab. It has seen thousands of students pass through its 10-week-long programs, each of which regularly draws around 150 participants. During the course, students are exposed to topics from the history and practice of science to quantum mechanics to neutrino research at Fermilab.

Several copycat programs as near as the University of Michigan and as far as Darmstadt, Germany, attest to the program’s success instilling an appreciation of science and understanding of physics.

Neither snow nor rain nor heat have ever stopped the classes of Saturday Morning Physics, whose website warns students that “class is never cancelled due to weather.” According to Fermilab physicists Roger Dixon and Erik Ramberg, who have been directors of Saturday Morning Physics for more than 20 years, class has been cancelled only once: during the government shutdown of 2013.

This year, Dixon and Ramberg will pass down their directorial duties to University of Tennessee, Knoxville, physicist Sowjanya Gollapinni and Fermilab physicist Elliott McCrory. Gollapinni is a member of the MicroBooNE neutrino experiment, while McCrory, who works on Fermilab accelerators, brings with him nearly three decades of experience in training students through the Summer Internships in Science and Technology program.

While much of the physics that Dixon and Ramberg have taught has remained the same, the course has changed in other ways.

“Women joining has certainly increased over the years. It was very rare that we had more than five or six per session” in the early years, said Suzanne Weber, who has coordinated the program since 1990. Now, nearly half of each class is made up of female students.

Fermilab scientist Dan Hooper teaches the first class of Saturday Morning Physics in 2017. Photo: Elliott McCrory

Moving forward, McCrory and Gollapinni will work to continue making Saturday Morning Physics inclusive.

“We’re considering how we can add a lecture in Spanish,” McCrory said.

For Gollapinni, the importance of the lecturers as role models can’t be understated.

“It’s important for them to see all types of role models,” she said. “As a woman myself, seeing a female role model speak matters to the extent that it makes you feel like you can do anything, because you see a person like you, who has reached higher points in their career.”

Both McCrory and Gollapinni, a member of the community of university scientists who use the Fermilab for their research, also emphasized the need to experiment with the course and try new approaches to teaching physics.

“When we talk about particle physics — we’re studying essentially invisible things. So how do we know that they’re really there? It’s by the scientific method. We want the lecturers to at least touch on that concept throughout the year,” McCrory said.

Demos and other hands-on activities like tours that break up the standard two-hour lecture will also be emphasized as learning aids, Gollapinni said.

Dixon and Ramberg said they look forward to seeing where McCrory and Gollapinni take the venerated program.

“The thing that I always told the parents, which I always believed, is that the program was as much for us as it was for the kids,” Dixon said.

“This is one of the greatest tools to connect the laboratory with the community,” Ramberg said. “It really affects generations of kids.”

Thanks to recent upgrades to the Main Injector, Fermilab’s flagship accelerator, Fermilab scientists have produced 700-kilowatt proton beams for the lab’s experiments. Photo: Peter Ginter

Fermilab’s accelerator is now delivering more neutrinos to experiments than ever before.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory has achieved a significant milestone for proton beam power. On Jan. 24, the laboratory’s flagship particle accelerator delivered a 700-kilowatt proton beam over one hour at an energy of 120 billion electronvolts.

The Main Injector accelerator provides a massive number of protons to create particles called neutrinos, elusive particles that influence how our universe has evolved. Neutrinos are the second-most abundant matter particles in our universe. Trillions pass through us every second without leaving a trace.

Because they are so abundant, neutrinos can influence all kinds of processes, such as the formation of galaxies or supernovae. Neutrinos might also be the key to uncovering why there is more matter than antimatter in our universe. They might be one of the most valuable players in the history of our universe, but they are hard to capture and this makes them difficult to study.

“We push always for higher and higher beam powers at accelerators, and we are lucky our accelerator colleagues live for a challenge,” said Steve Brice, head of Fermilab’s Neutrino Division. “Every neutrino is an opportunity to study our universe further.”

With more beam power, scientists can provide more neutrinos in a given amount of time. At Fermilab, that means more opportunities to study these subtle particles at the lab’s three major neutrino experiments: MicroBooNE, MINERvA and NOvA.

“Neutrino experiments ask for the world, if they can get it. And they should,” said Dave Capista, accelerator scientist at Fermilab. Even higher beam powers will be needed for the future international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, to be hosted by Fermilab. DUNE, along with its supporting Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility, is the largest new project being undertaken in particle physics anywhere in the world since the Large Hadron Collider.

“It’s a negotiation process: What is the highest beam power we can reasonably achieve while keeping the machine stable, and how much would that benefit the neutrino researcher compared to what they had before?” said Fermilab accelerator scientist Mary Convery.

“This step-by-step journey was a technical challenge and also tested our understanding of the physics of high-intensity beams,” said Fermilab Chief Accelerator Officer Sergei Nagaitsev. “But by reaching this ambitious goal, we show how great the team of physicists, engineers, technicians and everyone else involved is.” The 700-kilowatt beam power was the goal declared for 2017 for Fermilab’s accelerator-based experimental program.

Particle accelerators are complex machines with many different parts that change and influence the particle beam constantly. One challenge with high-intensity beams is that they are relatively large and hard to handle. Particles in accelerators travel in groups referred to as bunches.

Roughly one hundred billion protons are in one bunch, and they need their space. The beam pipes – through which particles travel inside the accelerator – need to be big enough for the bunches to fit. Otherwise particles will scrape the inner surface of the pipes and get lost in the equipment.

The Main Injector, a 2-mile-circumference racetrack for protons, is the most powerful particle accelerator in operation at Fermilab. It provides proton beams for various particle physics experiments as well as Fermilab Test Beam Facility. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Such losses, as they’re called, need to be controlled, so while working on creating the conditions to generate a high-power beam, scientists also study where particles get lost and how it happens. They perform a number of engineering feats that allow them to catch the wandering particles before they damage something important in the accelerator tunnel.

To generate high-power beams, the scientists and engineers at Fermilab use two accelerators in parallel. The Main Injector is the driver: It accelerates protons and subsequently smashes them into a target to create neutrinos. Even before the protons enter the Main Injector, they are prepared in the Recycler.

The Fermilab accelerator complex can’t create big bunches from the get-go, so scientists create the big bunches by merging two smaller bunches in the Recycler. A small bunch of protons is sent into the Recycler, where it waits until the next small bunch is sent in to join it. Imagine a small herd of cattle, and then acquiring a new herd of the same size. Rather than caring for them separately, you allow the two herds to join each other on the big meadow to form a big herd. Now you can handle them as one herd instead of two.

In this way Fermilab scientists double the number of particles in one bunch. The big bunches then go into the Main Injector for acceleration. This technique to increase the number of protons in each bunch had been used before in the Main Injector, but now the Recycler has been upgraded to be able to handle the process as well.

“The real bonus is having two machines doing the job,” said Ioanis Kourbanis, who led the upgrade effort. “Before we had the Recycler merging the bunches, the Main Injector handled the merging process, and this was time consuming. Now, we can accelerate the already merged bunches in the Main Injector and meanwhile prepare the next group in the Recycler. This is the key to higher beam powers and more neutrinos.”

Fermilab scientists and engineers were able to marry two advantages of the proton acceleration technique to generate the desired truckloads of neutrinos: increase the numbers of protons in each bunch and decrease the delivery time of those proton to create neutrinos.

“Attaining this promised power is an achievement of the whole laboratory,” Nagaitsev said. “It is shared with all who have supported this journey.”

The new heights will open many doors for the experiments, but no one will rest long on their laurels. The journey for high beam power continues, and new plans for even more beam power are already under way.