It was in 1979. I was visiting the Fermilab on release from CERN, as a guest scientist, and enjoying the wonderful spirit of a young laboratory of world standing. It was a privilege, and my wife and I were able to rent a house on the site at Sauk Circle, right where the action was and conveniently near the various labs and workshops.

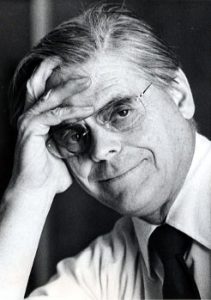

The director, Leon Lederman, had a house on the site too, and he and his wife Ellen had invited us to a dinner party one evening. On this occasion they had asked Leon’s secretary and a notable guest, Robert Wilson, the founder of the lab and Leon’s predecessor. Very exciting.

An interesting dinner guest was Professor Wilson. He regaled us with stories of the early days of the lab, and how he had juggled with his duties at the lab and his professorial responsibilities in Ithaca, New York, by commuting in chartered aircraft at least once a week.

He also told the story of the walnut trees, which I now repeat for the record.

Soon after the site was designated and taken over by the U.S. government, and before a security fence and checkpoints were in place, some thieves succeeded in cutting down several beautiful, mature walnut trees, the trunks of which they were clearly intending to collect and sell for a considerable sum. As it happens, they never returned to remove them for fear of apprehension now that their misdeed had been noticed.

Robert Rathbun Wilson was faced with a dilemma. Obviously this valuable resource, the property of the United States, had to be exploited for the benefit of its owners as efficiently as possible. After making inquiries, he discovered that because walnut was used to make veneer for fine furniture, these tree trunks were potentially very valuable. Thousands of dollars were involved. He decided to store the tree trunks as a budget reserve which would come in useful if he ever had to deal with a shortfall.

Three or four years later, the opportunity arose to use his timber nest egg. He then discovered what his informants had failed to tell him. The tree has to be reduced to veneer within a short time of felling. Disappointing. By now, it was just high-class furniture wood. Its potential as a source of veneer had been lost and its value was considerably lower.

He decided to make the best of it. The now seasoned timber would be used for the benefit of the newly constructed high-rise building.

And that is why the handrails in all the stairways of what is now called Wilson Hall are made of the very finest solid American Walnut.

Frank Beck is a retired CERN staff member living in England. He spent two years at the Fermilab as head of research services when the Energy Saver was being commissioned.

Editor’s note: Since posting this article, a couple of readers have chimed in with more information about the fate of the walnut trees. Some of the wood went into the construction of Ramsey Auditorium. Check out the History and Archives Project and a 1971 issue and a 1976 issue of The Village Crier (see page 2 in both). Read about the preservation of trees on the lab site and see a photo of the walnut trees from 1969 (here’s the 1969 newsletter). The same wood was used in 1981 to make the letters on the auditorium.

The puzzle: understanding how nearly undetectable particles, called neutrinos, interact with normal matter. The solution? The clever MINERvA experiment, which shares its name with the Roman goddess of wisdom.

MINERvA, the Main INjector ExpeRiment for ν-A (where v is a symbol for neutrinos) is the world’s first neutrino experiment to use a high-intensity beam to study neutrino interactions with multiple nucleus sizes at the same time.

MINERvA scientists are currently looking at how low-energy neutrinos interact with ordinary matter like the protons and neutrons that make up the center of the atom. Specifically, MINERvA’s international collaboration of university and lab scientists is studying what happens when neutrinos interact with different elements from helium all the way to lead, which have different sized atomic parts.

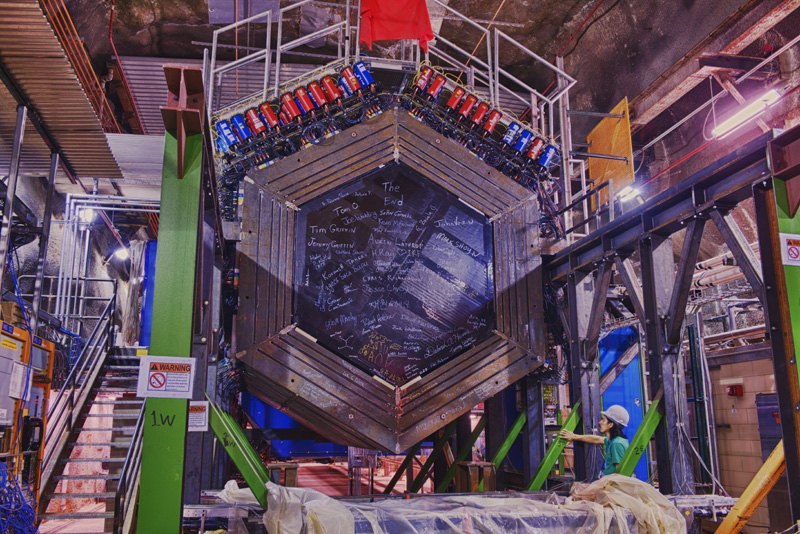

The front face of the MINERvA detector sits in its underground home near the end of construction. This front face is no longer visible because of the helium target that was installed upstream. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Imagine an atomic nucleus as racked up pool balls with little springs attached to each other and the neutrino beam as the cue ball. It’s pretty easy to see what happens if you hit the pool balls with very little energy (almost nothing happens) or a lot of energy (they all break apart). But scientists need to know what happens with neutrinos in that middle energy level.

“Some of the energy goes into breaking springs, some goes into breaking apart pool balls. Some goes into ejecting pool balls with energy,” said MINERvA co-spokesperson Kevin McFarland, a researcher at the University of Rochester. “Because it’s such a complicated system — you’re getting a big nucleus full of lots of neutrons and protons bound together with springs — it’s really hard to look at what comes out and infer precisely what the energy of the neutrino was.”

By better understanding how neutrinos interact with the matter all around us, researchers hope to improve our model of how physics — and the universe — works. The information can be used in simulations of other neutrino experiments to correct for the energy that isn’t seen in these interactions and to improve accuracy.

This information is crucial both for current neutrino experiments such as NOvA and in preparation for upcoming neutrino oscillation experiments such as the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, or DUNE. At the energies required for those projects, the components of the nucleus begin to break apart, producing a slew of different particles and complex data.

“We’re making measurements that haven’t been measured ever before,” said Minerba Betancourt, postdoctoral researcher for MINERvA. “For example, there’s a channel called quasielastic, in which a neutrino interacts with the detector and produces a muon and a proton. For that type of neutrino interaction, there are not any measurements of iron or lead to scintillator ratios.”

Making new neutrinos

A lot has to happen to produce MINERvA data. The experiment uses Fermilab’s Main Injector accelerator, which produces protons at energies of over 120 times their rest masses. These protons smash into a carbon target in the NuMI beamline, producing particles called pions that then transform into the desired neutrinos.

Sooner or later, a tiny fraction of these neutrinos interact with nuclei in the detector and produce daughter particles. These particles leave the nucleus, causing interactions that produce light in the scintillator detector that scientists record and analyze.

“Neutrinos are neutral, so they don’t have a charge. We can’t see them until they actually produce something,” said Daniel Ruterbories, a postdoctoral researcher for MINERvA. “All of a sudden, particles spontaneously appear.”

MINERvA has a unique ability to study neutrinos with high precision, primarily because of its detector technology. Those detector components, called scintillator bars, are small. That means physicists can measure neutrino interactions in more detail than a typical neutrino detector, which has to be huge because it has to be located hundreds of miles away from the neutrino source.

Moving forward, MINERvA will analyze higher-energy neutrinos. By taking data at about 6 GeV of energy instead of the previous 3 GeV, scientists will be able to study many more interactions in the detector.

“We’re producing a large bucket of events,” Ruterbories said. “We should be able to really focus down and try to answer the questions of how these interactions occur.”

Calling all nature lovers. How would you like the chance to help diversify one of the oldest prairie restorations in Illinois?

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is looking for volunteers to help with its annual prairie seed harvest. Two harvest events are planned, on Saturday, Sept. 10 and Saturday, Oct. 15, beginning at 10 a.m. Fermilab’s site hosts 1,000 acres of restored native prairie land, and each year community members pitch in to help collect seeds from those native plants.

Less than one-tenth of one percent of native prairies in Illinois remains intact. Fermilab’s restored grassland, begun 41 years ago, is one of the largest prairies in the state. The deep-rooted natural grasses of the prairie help prevent erosion and preserve the area’s aquifers.

The main collection area spans about 100 acres, and within it, volunteers will gather seeds from about 25 different types of native plants. Some of those seeds will be used to replenish the Fermilab prairies, filling in gaps where some species are more dominant than others.

“Our objective is to collect seeds from dozens of species,” said Ryan Campbell, an ecologist at Fermilab. “We have more than 1,000 acres of restored grassland, and it’s not all of the same quality. We want to spread diversity throughout the whole site.”

Once the seeds have been collected, the Fermilab roads and grounds staff will store them in a greenhouse and process them for springtime planting, once controlled burns of the prairie have been conducted. The laboratory has also donated some of the seeds to area schools for use in their own prairies and as educational tools.

Fermilab has been hosting the Prairie Harvest every year since 1974, and the event typically draws more than 200 volunteers. The event will last from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., with lunch provided. Volunteers will be trained on different types of plants and how to harvest seeds. If you have them, bring gloves, a pair of hand clippers and paper grocery bags.

In case of inclement weather, call the Fermilab switchboard at 630-840-3000 to check whether the Prairie Harvest has been canceled. More information on Fermilab’s prairie can be found on our website. For more information on the Prairie Harvest, call the Fermilab Roads and Grounds Department at 630-840-3303.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.