Scientists this week heard their first pops in an experiment that searches for signs of dark matter in the form of tiny bubbles.

Scientists will need further analysis to discern whether dark matter caused any of the COUPP-60 experiment’s first bubbles.

“Our goal is to make the most sensitive detector to see signals of particles that we don’t understand,” said Hugh Lippincott, a postdoc with the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory who has spent much of the past several months leading the installation of the one-of-a-kind detector in a laboratory a mile and a half underground.

COUPP-60 is a dark-matter experiment funded by DOE’s Office of Science. Fermilab managed the assembly and installation of the experiment’s detector.

The COUPP-60 detector is a jar filled with purified water and CF3I—an ingredient found in fire extinguishers. The liquid in the detector is kept at a temperature and pressure slightly above the boiling point, but it requires an extra bit of energy to actually form a bubble. When a passing particle enters the detector and disturbs an atom in the clear liquid, it provides that energy.

Dark-matter particles, which scientists think rarely interact with other matter, should form individual bubbles in the COUPP-60 tank.

“The events are so rare, we’re looking for a couple of events per year,” Lippincott said.

Other, more common and interactive particles such as neutrons are more likely to leave a trail of multiple bubbles as they pass through.

Over the next few months, scientists will analyze the bubbles that form in their detector to test how well COUPP-60 is working and to determine whether they see signs of dark matter. One of the advantages of the detector is that it can be filled with a different liquid, if scientists decide they would like to alter their techniques.

The COUPP-60 detector is the latest addition to a suite of dark-matter experiments running in the SNOLAB underground science laboratory, located in Ontario, Canada. Scientists run dark-matter experiments underground to shield them from a distracting background of other particles that constantly shower Earth from space. Dark-matter particles can move through the mile and a half of rock under which the laboratory is buried, whereas most other particles cannot.

Scientists further shield the COUPP-60 detector from neutrons and other particles by submersing it in 7,000 gallons of water.

Scientists first proposed the existence of dark matter in the 1930s, when they discovered that visible matter could not account for the rotational velocities of galaxies . Other evidence, such as gravitational lensing that distorts our view of faraway stars and our inability to explain how other galaxies hold together if not for the mass of dark matter, have improved scientists’ case. Astrophysicists think dark matter accounts for about a quarter of the matter and energy in the universe. But no one has conclusively observed dark-matter particles.

The COUPP experiment includes scientists, technicians and students from the University of Chicago, Indiana University South Bend, Northwestern University, Universitat politècnica de València, Virginia Tech, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and SNOLAB.

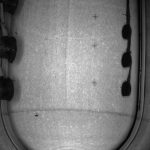

- Image of one of the first bubbles seen in the COUPP-60 detector, located a mile and a half underground at SNOLAB in Ontario, Canada. The bubble appears as a black semi-circle on the lower left-hand side of the image. The white ovals in the center are reflections of LED lights. Photo: SNOLAB

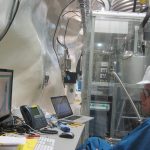

- COUPP-60 collaboration members Andrew Sonnenschein and Hugh Lippincott monitoring the filling of the detector at SNOLAB in Ontario, Canada. Photo: SNOLAB

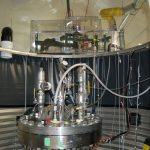

- The COUPP-60 detector installed at the SNOLAB underground laboratory in Ontario, Canada. Photo: SNOLAB

- The COUPP-60 detector installed at the SNOLAB underground laboratory in Ontario, Canada. Photo: SNOLAB

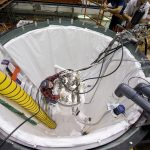

- Scientists install the COUPP-60 detector a mile and a half underground at SNOLAB in Ontario, Canada. Photo: Fermilab

- The COUPP-60 detector was assembled by Fermilab. It consists of a jar filled with water and an element used in fire extinguishers, which is then shielded and submerged in more water underground. Photo: Fermilab

- Scientists at Fermilab built and tested a prototype version of the COUPP-60 detector in 2009. Photo: Fermilab

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

It’s that time of year again.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory welcomes the public to come see the latest additions to its herd of American bison, commonly known as buffalo. Three calves have been born in the past few days, increasing the herd size to 25, and at least eight more calves are expected by early June.

Visitors, including families with young children, can enter the Fermilab site through its Pine Street entrance in Batavia or the Batavia Road entrance in Warrenville. Admission is free, but you will need a valid photo ID to enter the site. Summer hours are from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., seven days a week.

Fermilab’s first director, Robert Wilson, established the bison herd in 1969 as a symbol of the history of the Midwestern prairie and the laboratory’s pioneering research at the frontiers of particle physics. The herd remains a major attraction for families and wildlife enthusiasts. Today, the Fermilab site also boasts 1,100 acres of reconstructed tall-grass prairie as well as seven particle accelerators. The U.S. Department of Energy designated the 6,800-acre Fermilab site a National Environmental Research Park in 1989.

Visitors can learn more about nature at Fermilab by hiking the Interpretive Prairie Trail, a half-mile-long trail located near the Pine Street entrance. The Leon Lederman Science Education Center offers exhibits on the prairie and hands-on physics displays. The Lederman Center hours are Monday-Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and Saturdays from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.

For up-to-date information for visitors, please visit www.fnal.gov or call (630) 840-3351.

To learn more about Fermilab’s bison herd, please visit our website at www.fnal.gov/pub/about/campus/ecology/wildlife/bison.html.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

Batavia, IL – What does a scientist actually do all day? How difficult is it to be a mechanical engineer? What is the daily life of a computer technician really like? How much and what type of math is used in these types of careers?

On Wednesday, April 10, from 5:30 to 8:30 p.m., the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory will offer high -school students a valuable opportunity to ask those questions in person. The annual Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Career Expo, held in the atrium of Wilson Hall, will put these students face to face with people actually doing the kinds of jobs they will be applying for in the coming years.

In addition to Fermilab scientists and engineers, the STEM Career Expo will feature professionals of several local companies and research organizations, on hand to explain what they do. But this is not a college or job fair and is not about recruiting, according to organizer Susan Dahl of the Fermilab Office of Education.

Rather, she said, this is a chance for students to talk one-on-one with professionals working in their fields of interest. The expo will also include five panel discussions on STEM-related topics, with an opportunity for students to ask questions.

“We hope students come away with a new view of the possibilities of finding careers in these fascinating fields and a more realistic idea of the individuals working in these very relevant and fascinating jobs,” Dahl said.

The STEM Career Expo is free and open to all high -school students. The event is a collaborative event organized by the Fermilab Education Office and educators and career specialists from Kane and DuPage county schools. Sponsors include Fermilab Friends for Science Education, Batavia High School, Geneva Community High School and Northern Kane County Region EFE 110.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and is operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov, and follow Fermilab on Facebook at www.facebook.com/fermilab and on Twitter @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

What will soon be the most powerful neutrino detector in the United States has recorded its first three-dimensional images of particles.

Using the first completed section of the NOvA neutrino detector, scientists have begun collecting data from cosmic rays—particles produced by a constant rain of atomic nuclei falling on the Earth’s atmosphere from space .

“It’s taken years of hard work and close collaboration among universities, national laboratories and private companies to get to this point,” said Pier Oddone, director of the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Fermilab manages the project to construct the detector.

The active section of the detector, under construction in Ash River, Minn., is about 12 feet long, 15 feet wide and 20 feet tall. The full detector will measure more than 200 feet long, 50 feet wide and 50 feet tall.

Scientists’ goal for the completed detector is to use it to discover properties of mysterious fundamental particles called neutrinos. Neutrinos are as abundant as cosmic rays in the atmosphere, but they have barely any mass and interact much more rarely with other matter . Many of the neutrinos around today are thought to have originated in the big bang.

“The more we know about neutrinos, the more we know about the early universe and about how our world works at its most basic level,” said NOvA co-spokesperson Gary Feldman of Harvard University.

Later this year, Fermilab, outside of Chicago, will start sending a beam of neutrinos 500 miles through the earth to the NOvA detector near the Canadian border. When a neutrino interacts in the NOvA detector , the particles it produces leave trails of light in their wake. The detector records these streams of light , enabling physicists to identify the original neutrino and measure the amount of energy it had.

When cosmic rays pass through the NOvA detector, they leave straight tracks and deposit well-known amounts of energy. They are great for calibration, said Mat Muether, a Fermilab post-doctoral researcher who has been working on the detector.

“Everybody loves cosmic rays for this reason,” Muether said. “They are simple and abundant and a perfect tool for tuning up a new detector.”

The detector at its current size catches more than 1,000 cosmic rays per second. Naturally occurring neutrinos from cosmic rays, supernovae and the sun stream through the detector at the same time. But the flood of more visible cosmic -ray data makes it difficult to pick them out.

Once the upgraded Fermilab neutrino beam starts, the NOvA detector will take data every 1.3 seconds to synchronize with the Fermilab accelerator . Inside this short time window, the burst of neutrinos from Fermilab will be much easier to spot.

The NOvA detector will be operated by the University of Minnesota under a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

The NOvA experiment is a collaboration of 180 scientists, technicians and students from 20 universities and laboratories in the U.S and another 14 institutions around the world. The scientists are funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and funding agencies in the Czech Republic, Greece, India, Russia and the United Kingdom.

Additional resources:

- NOvA project website: http://www-nova.fnal.gov

- NOvA: Exploring Neutrino Mysteries video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fe4veClYxkE

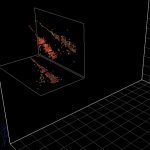

- This 3D image shows a cosmic-ray muon producing a large shower of energy as it passes through the NOvA far detector in Minnesota. Image courtesy NOvA collaboration

- This 3D image shows a cosmic-ray muon producing a large shower of energy as it passes through the NOvA far detector in Minnesota. Image courtesy NOvA collaboration

- The NOvA detector, currently under construction in Ash River, Minn., stands about 50 feet tall and 50 feet wide. The completed detector will weigh 14,000 tons. Photo: Fermilab

- When completed, the NOvA detector will comprise 28 detector blocks, each measuring about 50 feet tall, 50 feet wide and 6 feet deep. Photo: Fermilab

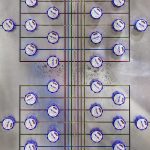

- Electronics that make up part of the data acquisition system are installed on the top and side of the detector. The NOvA experiment is a collaboration of 169 scientists from 19 universities and laboratories in the U.S and another 15 institutions around the world. The scientists are funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and funding agencies in the Czech Republic, Greece, India, Russia and the United Kingdom. Photo: Fermilab

- Technicians glue modules for the NOvA detector using a machine developed at Argonne National Laboratory. Photo: William Miller, NOvA installation manager

- Scientists and engineers at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory developed the 750,000-pound pivoter machine that will put the blocks of the NOvA detector in place. Photo: Fermilab

- The NOvA detector, located in Ash River, Minn., will study a beam of neutrinos originating 500 miles away at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, located near Chicago. Image: Fermilab

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Editor’s note: The following US LHC press release was issued jointly by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Fermilab is heavily involved in the Higgs boson research at the Large Hadron Collider. The Illinois laboratory serves as the U.S. hub for more than 1,000 scientists and engineers (roughly 120 of whom work at Fermilab) who participate in the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment, one of two large-scale high-energy experiments using the LHC.

Fermilab houses a remote operations center for the CMS experiment in which scientists monitor the data generated at the CMS detector in Switzerland. Fermilab provides about one-quarter of the CMS experiment’s computing power. Fermilab scientists, engineers and technicians made significant contributions to the design and construction of both the LHC and the CMS detector and are working on upgrades to both machines.

“With the results released today, it is looking more likely that we have found the Standard Model Higgs boson, and that may lead to significant answers about the nature of our universe,” said Fermilab Director Pier Oddone. “We remain proud of the contributions Fermilab and other U.S. scientists, engineers and students have made to this discovery.”

The new particle discovered at experiments at the Large Hadron Collider last summer is looking more like a Higgs boson than ever before, according to results announced today.

On July 4, physicists on the CMS and ATLAS experiments announced the discovery of a particle with a close resemblance to a Higgs, a particle thought to give mass to other elementary particles. The discovery of such a particle could finish a job almost five decades in the making: It could confirm the last remaining piece of the Standard Model of particle physics, a menu of the smallest particles and forces that make up the universe and how they interact.

Although scientists will need to analyze substantially more data before they can conclusively declare the new particle is the Standard Model Higgs boson, results announced today at the Rencontres de Moriond conference in La Thuile, Italy, bolster scientists’ confidence that the particle they discovered is the Standard Model Higgs.

“Clear evidence that the new particle is the Standard Model Higgs boson still would not complete our understanding of the universe,” said Patty McBride, head of the CMS Center at Fermilab. “We still wouldn’t understand why gravity is so weak and we would have the mysteries of dark matter to confront. But it is satisfying to come a step closer to validating a 48-year-old theory.”

Researchers look for the Higgs boson at the LHC by accelerating protons to high energies and crashing them into one another. The energy of those colliding protons can briefly convert into mass, bringing into being heavier particles such as the Higgs bosons. The heavy particles are unstable and decay almost immediately into pairs of less massive particles.

Scientists have specific predictions for how often a Standard Model Higgs boson of a certain mass will decay into different patterns of particles. The latest results indicate that the new particle is sticking to the Standard Model’s script.

The ATLAS and CMS collaborations have analyzed two and a half times more data than was available for the discovery announcement in July, and, in their preliminary results, they find that the new particle is looking more and more like a Higgs boson.

“When we discovered the particle, we knew we found something significant,” ATLAS scientist and New York University professor Kyle Cranmer said. “Now, we’re just trying to establish the properties.”

The analysis included the data from about 500 trillion proton-proton collisions collected in 2011 and from about 1,500 trillion collisions in 2012. The LHC stopped operation on Feb. 16, for two years of maintenance and upgrades, but researchers will continue to study the data collected before the shutdown.

Hundreds of scientists and students from American institutions have played important roles in the search for the Higgs at the LHC. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and Brookhaven National Laboratory host the U.S. contingents of the CMS and ATLAS experiments, respectively. More than 1,700 people from U.S. institutions–including 89 American universities and seven U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) national laboratories–helped design, build and operate the LHC accelerator and its four particle detectors. The United States, through DOE’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation, provides support for research, detector operations, and upgrades at the LHC, as well as supplies computing for the ATLAS and CMS experiments.

The vast majority of U.S. scientists participate in the LHC experiments from their home institutions, remotely accessing and analyzing the data through high-capacity networks and grid computing. Working collaboratively, these international organizations are able to analyze an incredible amount of data.

After further analysis, scientists will be able to say whether this new particle is the Standard Model Higgs boson or something more surprising.

Background:

Information about the US participation in the LHC is available at http://www.uslhc.us . Follow US LHC on Twitter at http://twitter.com/uslhc.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @FermilabToday.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is operated and managed for DOE’s Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates. Visit Brookhaven Lab’s electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more: http://www.bnl.gov/newsroom.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov .

The National Science Foundation focuses its LHC support on funding the activities of U.S. university scientists and students on the ATLAS, CMS and LHCb detectors, as well as promoting the development of advanced computing innovations essential to address the data challenges posed by the LHC. For more information, please visit http://www.nsf.gov/.

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, is the world’s leading laboratory for particle physics. It has its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. At present, its Member States are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Romania is a candidate for accession. Israel and Serbia are Associate Members in the pre-stage to Membership. India, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States of America, Turkey, the European Commission and UNESCO have Observer status.

Fact sheets, images, graphics and videos:

Illustration: Standard Model particles

- Med res: http://www-visualmedia.fnal.gov/VMS_Site/gallery/stillphotos/2005/0400/05-0440-01D.jpg

- High res: http://www-visualmedia.fnal.gov/VMS_Site/gallery/stillphotos/2005/0400/05-0440-01D.hr.jpg

Photo: Remote Operations Center at Fermilab

- Med-res: http://www-visualmedia.fnal.gov/VMS_Site/gallery/stillphotos/2011/0000/11-0009-08D.jpg

- High-res: http://www-visualmedia.fnal.gov/VMS_Site/gallery/stillphotos/2011/0000/11-0009-08D.hr.jpg

Video: What is a Higgs boson?

Video: How do we search for Higgs bosons?

Fact sheet: Frequently Asked Questions about the Higgs boson:

Definitions of important terms:

Photos in the CERN photo archive:

Fermilab Director Pier Oddone (right) accepts the ISO 20000 certificate from UL DQS CEO Ganesh Rao on Feb. 13 at Fermilab. Photo: Fermilab

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory has earned ISO 20000 certification for excellence in information technology service management. Fermilab is the first of the Department of Energy’s 17 national laboratories to earn this certification.

ISO 20K is a global standard for companies and organizations who provide quality IT services. The standard was developed in 2005 (and revised in 2011), and any organization can apply for ISO 20K assessment and certification.

Fermilab’s assessment was conducted over several years, and included 13 services that are fundamental to the laboratory. These included the IT service desk, the lab-wide email system, and all network services, including Internet connections. Fermilab must submit an annual audit and a plan to continually improve services to maintain this certification.

“This significant accomplishment demonstrates the continuing commitment to IT excellence at all of the Department of Energy’s national laboratories,” said Michael Weis, Fermilab site manager with the DOE’s Office of Science.

Fermilab’s Computing Sector received the official certification in December and a ceremony was held at the laboratory on Wednesday, Feb. 13.

“Since we began the ISO 20K certification process several years ago, our goal has been to deliver the best possible IT-related services,” said Victoria White, Fermilab’s associate director for computing and chief information officer. “Moving forward, we will continue to create a better computing experience for our 1,750 employees and more than 2,000 scientific users.”

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and is operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov, and follow Fermilab on Facebook at www.facebook.com/fermilab and on Twitter @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

The judges have spoken, and the winners have been chosen in this year’s Fermilab Photowalk competition.

On Sept. 22, the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Ill., invited 50 amateur and professional photographers to take pictures in five high-tech areas of the lab, areas not part of the public tour. The photographers, chosen on a first-come, first-served basis, were then asked to submit their best shots to a panel of five local Photowalk judges.

Earlier this month, the judges selected their favorites from the 234 submissions. Their choices range from close-up shots of machinery to depictions of the iconic Wilson Hall, some in color and others in stark black and white. The judging process was spirited, requiring several rounds of voting to arrive at the 25 favorites.

The winning photo was taken by Stan Kirschner of Mundelein, Ill. Kirschner has been a photography enthusiast since he was 13, when his parents bought him his first camera – a Kodak Baby Brownie Special. He has taught photography at the University of Vermont and is active in two camera clubs.

“I feel very honored to be a participant in Fermilab’s 2012 Photowalk,” Kirschner said. “What a wonderful opportunity and experience to learn about particle physics and be able to look for creative images to photograph.”

Brian Schultz of Naperville, Ill., snapped the second- and third-place photos. Matthew Swenson of Wood Dale, Ill., took the fourth-place picture, and John Williams of Mundelein, Ill., captured the fifth-place image.

The top 25 photos have been posted online at the Fermilab website, and will be featured on a new exhibit to be displayed in the Wilson Hall atrium. The top five photos will be entered into the international Photowalk competition, run by the particle physics collaboration Interactions.org. A total of 10 laboratories around the world will take part in the contest, with public voting set to begin in December.

Fermilab was one of two U.S. Department of Energy laboratories to participate in this year’s Photowalk. The other, Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, has also chosen their top five photos for the international competition. Brookhaven’s winners can be seen here.

Fermilab’s Photowalk drew participants from as far away as Atlanta, Ga. It’s the second time Fermilab has held a Photowalk, and the first since 2010.

This year’s panel of judges:

- Michael Branigan s the co-owner of Sandbox Studio, Chicago, a small communication design firm founded in 1998. Since 2004, Michael has collaborated on myriad science communication projects for Fermilab, SLAC, Argonne National Laboratory and the DOE Office of Science, to name a few, and has worked on symmetry magazine.

- Steve Buyansky started his career in photography at the Beacon-News in Aurora in 1983. He became photo editor at the Herald-News in Joliet in 2000. He is now a photo editor for Sun-Times Media, responsible for the Beacon-News, the Courier-News and the Naperville Sun.

- Marty Murphy works in the Fermilab Accelerator Operations Department and is a member of the Fermilab Photo Club. He is an avid photographer and has photographed Fermilab’s landscapes, machines, people and wildlife for the past 15 years.

- Jessica Orwig is a science writing intern for Fermilab’s Office of Communication. She is a graduate student at Texas A&M University, studying science and technology journalism.

- Georgia Schwender has been the visual arts coordinator at Fermilab since 2001 and operates the second-floor art gallery at Wilson Hall. She graduated from the Art Institute of Boston and previously worked at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and is operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov, and follow Fermilab on Facebook at www.facebook.com/fermilab and on Twitter @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Top three photos

- First place photo by Mike Baker, Bolingbrook, Illinois

- Second place photo by Mike Baker, Bolingbrook, Illinois

- Third place photo by Nelson Mark, Middletown, Indiana

Honorable mentions

- Photo by Steve Horne, Naperville, Illinois

- Photo by Karen Wade, Aurora, Illinois

- Photo by John Burkowski, Warrenville, Illinois

- Photo by Alton Yeager, Lombard, Illinois

- Photo by Krsto Sitar, Cicero, Illinois

- Photo by Daisy Su, Naperville, Illinois

- Photo by James Wills, Anderson, Indiana

- Photo by Daisy Su, Naperville, Illinois

- Photo by Lynda Roberts, Aurora, Illinois

- Photo by Daisy Su, Naperville, Illinois

- Photo by Johnathan Chung, Chicago, Illinois

- Photo by Juan Pablo Cruz Bastida, Madison, Wisconsin

- Photo by Steve Horne, Naperville, Illinois

- Photo by Diana Chrisman, Bloomingdale, Illinois

- Photo by Tania DePue, Redmond, Washington

- Photo by Nelson Mark, Middletown, Indiana

- Photo by Milosh Kosanovich, Chicago, Illinois

- Photo by Daisy Su, Naperville, Illinois

- Photo by Nelson Mark, Middletown, Indiana

- Photo by Richard Fisher, Wilmette, Illinois

BATAVIA, IL – Calling all nature lovers. How would you like the chance to help diversify one of the oldest prairie restorations in Illinois?

The Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is looking for volunteers to help with its annual prairie seed harvest on Saturday, Nov. 3. Fermilab’s site hosts 1,000 acres of restored native prairie land, and each year community members pitch in to help collect seeds from those native plants .

Fewer than one-tenth of one percent of native prairies in Illinois remain intact. Fermilab’s restored grassland represents one of the largest prairies in the state. The deep-rooted natural grasses of the prairie help prevent erosion and preserve the area’s aquifers.

The main collection area spans about 100 acres, and within it, volunteers will gather seeds from about 25 different types of native plants. Some of those seeds will be used to replenish the Fermilab prairies, filling in gaps where some species are more dominant than others.

“Our objective is to collect seeds from dozens of species,” said Ryan Campbell, an ecologist at Fermilab. “We have more than 1,000 acres of restored grassland, and it’s not all of the same quality. We want to spread diversity throughout the whole site.”

Once the seeds have been collected, the Fermilab roads and grounds staff will store them in a greenhouse, and process them for springtime planting, once controlled burns of the prairie have been conducted. The laboratory has also donated some of the seeds to area schools for use in their own prairies, and as educational tools.

Fermilab has been hosting the Prairie Harvest every year since 1974, and the event typically draws more than 200 volunteers. The event will last from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., with lunch provided. Volunteers will be trained on different types of plants, and how to harvest seeds. If you have them, bring gloves, a pair of hand clippers and paper grocery bags.

In case of inclement weather, call the Fermilab switchboard at 630-840-3000 to check whether the prairie harvest has been canceled. More information on Fermilab’s prairie can be found at http://www.fnal.gov/pub/about/campus/ecology/prairie. For more information on the Prairie Harvest, call the Fermilab Office of Communication at 630-840-3351.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @FermilabToday .

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

The University of Notre Dame has received a five-year, $6.1 million award from the National Science Foundation to support the nationwide QuarkNet program, which has inspired teachers and students alike for 15 years.

The University of Notre Dame has received a five-year, $6.1 million award from the National Science Foundation to support the nationwide QuarkNet program, which has inspired teachers and students alike for 15 years.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory plays a leading role in managing the QuarkNet program, which receives additional funding from the U.S. Department of Energy. QuarkNet uses particle physics experiments to provide valuable research, training, and mentorship opportunities for high school teachers. More than 500 teachers across the United States participate in the program.

Through the QuarkNet program, physicists at Fermilab, Notre Dame and 50 other research institutions will continue to mentor teachers in research experiences, enabling them to teach the basic concepts of introductory physics in a context that high school students find exciting. Faculty, teachers and their students work together as a community of researchers, which not only develops scientific literacy in students, but also attracts young students to careers in science and technology.

“The Notre Dame QuarkNet Center is a great example of the mentoring and training provided by particle physicists at universities and national laboratories across the country,” said Mitchell Wayne, Notre Dame professor of physics and principal investigator of the NSF grant. “It has become a focal point for educational outreach into our community.”

Fermilab and Notre Dame were two of the initial QuarkNet centers. Marge Bardeen, head of the Fermilab Education Office, started the Fermilab center 15 years ago. Her vision was to inspire and educate high school students who would be interested and engaged in particle physics. To reach these students meant reaching out to their teachers and engaging them in research.

“Fermilab and other research institutions can provide an experience that teachers and their students cannot find in other places,” Bardeen said. “They can help develop a broader framework for science. They can show how physicists discover new knowledge and talk about their work.”

One key feature of QuarkNet is the summer research experiences that participating centers offer for teachers and their students. During its first year, each QuarkNet center provides two teachers with eight-week research appointments and develops their expertise as lead teachers. In following years, each center may choose to host a teacher-student team for a research experience. This summer, for example, two teachers and eight students worked on seven different projects with Fermilab scientists, including investigations into dark matter and dark energy.

In the past few years, the reach of QuarkNet has become international, with QuarkNet activities such as cosmic-ray studies and masterclasses now available to teachers and their students around the world. This year, students in twenty-five countries are participating in the International Masterclasses, coordinated by the International Particle Physics Outreach Group. Held at university and laboratory centers, masterclasses are institutes for teams of students who become physicists for a day, analyze real experimental data and discuss results through videoconferences with physicists and peers across the world.

“They are looking at particle events, making determinations, doing counting themselves, coming to their own conclusions,” said Notre Dame’s Kenneth Cecire, who facilitates masterclasses in the United States.

Fermilab technicians have developed a cosmic-ray detector with a data acquisition system that allows high school students to conduct cosmic-ray studies in their classrooms. An e-Lab developed through an NSF grant to Fermilab allows students to upload and analyze cosmic- ray data and publish their results as online posters. QuarkNet offers professional development workshops for teachers to effectively use the detectors and e-Lab with their students. Fermilab has provided 700 cosmic-ray data acquisition systems to schools around the world, and over 1,000 teachers and 2,239 student research groups have e-Lab accounts.

As part of the QuarkNet program, teachers and their students have helped to build elements of the major Fermilab and Large Hadron Collider experiments over the last decade and are working on new detector upgrades. They are able to look at the latest scientific data from the LHC experiments, and use their own particle detectors to conduct measurements of cosmic rays.

During the next five years, the NSF grant will allow the QuarkNet program to expand and begin some new initiatives, including outreach into the Native American community.

“We are delighted to receive this new award and we are really looking forward to the next five years of QuarkNet,” Wayne said.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

Project website:

www.darkenergysurvey.org

Fact Sheet:

http://news.fnal.gov/wp-content/uploads/understanding-dark-energy.pdf

Eight billion years ago, rays of light from distant galaxies began their long journey to Earth. That ancient starlight has now found its way to a mountaintop in Chile, where the newly constructed Dark Energy Camera, the most powerful sky-mapping machine ever created, has captured and recorded it for the first time.

That light may hold within it the answer to one of the biggest mysteries in physics – why the expansion of the universe is speeding up.

Scientists in the international Dark Energy Survey collaboration announced this week that the Dark Energy Camera, the product of eight years of planning and construction by scientists, engineers, and technicians on three continents, has achieved first light. The first pictures of the southern sky were taken by the 570-megapixel camera on Sept. 12.

“The achievement of first light through the Dark Energy Camera begins a significant new era in our exploration of the cosmic frontier,” said James Siegrist, associate director of science for high energy physics with the U.S. Department of Energy. “The results of this survey will bring us closer to understanding the mystery of dark energy, and what it means for the universe.”

The Dark Energy Camera was constructed at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois, and mounted on the Victor M. Blanco telescope at the National Science Foundation’s Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile, which is the southern branch of the U.S. National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO). With this device, roughly the size of a phone booth, astronomers and physicists will probe the mystery of dark energy, the force they believe is causing the universe to expand faster and faster.

“The Dark Energy Survey will help us understand why the expansion of the universe is accelerating, rather than slowing due to gravity,” said Brenna Flaugher, project manager and scientist at Fermilab. “It is extremely satisfying to see the efforts of all the people involved in this project finally come together.”

The Dark Energy Camera is the most powerful survey instrument of its kind, able to see light from over 100,000 galaxies up to 8 billion light years away in each snapshot. The camera’s array of 62 charged-coupled devices has an unprecedented sensitivity to very red light, and along with the Blanco telescope’s large light-gathering mirror (which spans 13 feet across), will allow scientists from around the world to pursue investigations ranging from studies of asteroids in our own Solar System to the understanding of the origins and the fate of the universe.

“We’re very excited to bring the Dark Energy Camera online and make it available for the astronomical community through NOAO’s open access telescope allocation,” said Chris Smith, director of the Cerro-Tololo Inter-American Observatory. “With it, we provide astronomers from all over the world a powerful new tool to explore the outstanding questions of our time, perhaps the most pressing of which is the nature of dark energy.”

Scientists in the Dark Energy Survey collaboration will use the new camera to carry out the largest galaxy survey ever undertaken, and will use that data to carry out four probes of dark energy, studying galaxy clusters, supernovae, the large-scale clumping of galaxies and weak gravitational lensing. This will be the first time all four of these methods will be possible in a single experiment.

The Dark Energy Survey is expected to begin in December, after the camera is fully tested, and will take advantage of the excellent atmospheric conditions in the Chilean Andes to deliver pictures with the sharpest resolution seen in such a wide-field astronomy survey. In just its first few nights of testing, the camera has already delivered images with excellent and nearly uniform spatial resolution.

Over five years, the survey will create detailed color images of one-eighth of the sky, or 5,000 square degrees, to discover and measure 300 million galaxies, 100,000 galaxy clusters and 4,000 supernovae.

The Dark Energy Survey is supported by funding from the U.S. Department of Energy; the National Science Foundation; funding agencies in the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil, Germany and Switzerland; and the participating DES institutions.

More information about the Dark Energy Survey, including the list of participating institutions, is available at the project website: www.darkenergysurvey.org.

For a summary of the major components contributed to the Dark Energy Camera by the participating institutions, read these symmetry articles: www.symmetrymagazine.org/cms/?pid=1000880, http://www.symmetrymagazine.org/article/september-2012/the-dark-energy-camera-opens-its-eyes

Released by Fermilab and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO) on behalf of the Dark Energy Survey collaboration. NOAO is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), Inc. under cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @FermilabToday.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

- Zoomed-in image from the Dark Energy Camera of the center of the globular star cluster 47 Tucanae, which lies about 17,000 light years from Earth. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- Zoomed-in image from the Dark Energy Camera of the barred spiral galaxy NGC 1365, in the Fornax cluster of galaxies, which lies about 60 million light years from Earth. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- Zoomed-in image from the Dark Energy Camera of the Fornax cluster of galaxies, which lies about 60 million light years from Earth. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- Full Dark Energy Camera composite image of the globular star cluster 47 Tucanae, which lies about 17,000 light years from Earth. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

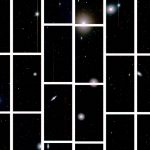

- Full Dark Energy Camera image of the Fornax cluster of galaxies, which lies about 60 million light years from Earth. The center of the cluster is the clump of galaxies in the upper portion of the image. The prominent galaxy in the lower right of the image is the barred spiral galaxy NGC 1365. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- Full Dark Energy Camera composite image of the Small Magellanic Cloud (a band of greenish stars running from lower left toupper right), a dwarf galaxy that lies about 200,000 light years from Earth, and is a satellite of our Milky Way galaxy. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

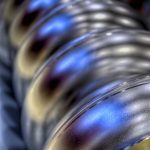

- The Dark Energy Camera features 62 charged-coupled devices (CCDs), which record a total of 570 megapixels per snapshot. Credit: Fermilab

- The Dark Energy Camera, mounted on the Blanco telescope in Chile. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- The Dark Energy Camera, mounted on the Blanco telescope in Chile. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- Dark Energy Camera telescope simulator at Fermilab. Credit: Fermilab

- Scientists build a prototype of the Dark Energy Camera, which will survey about one-tenth of the sky to measure 300 million galaxies and discover thousands of supernovae. Credit: Fermilab

- A simulation of a photo of galaxy clusters taken by the Dark Energy Camera. A single camera image captures an area 20 times the size of the moon as seen from Earth. Credit: Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- An artist’s rendering of the Dark Energy Camera inside the frame that supports the camera in the Blanco telescope. Credit: Fermilab/Dark Energy Survey Collaboration

- An artist’s rendering of the 570-megapixel Dark Energy Camera. Credit: Fermilab/DES collaboration

- The Blanco telescope in Chile as seen at nighttime. Credit: T. Abbott and NOAO/AURA/NSF

- The Blanco telescope in Chile as seen from the air. Credit: NOAO/AURA/NSF

- The Blanco telescope in Chile. Credit: T. Abbott and NOAO/AURA/NSF

- The 4 meter Blanco telescope. The green circle marks the location of the prime focus cage where the Dark Energy Camera will be mounted. Credit: CTIO/AURA/NSF

To download the first images captured by the Dark Energy Camera, go to http://www.noao.edu/news/2012/pr1204.php