The Dark Energy Survey (DES) collaboration is releasing results that, for the first time, combine all six years of data from weak lensing and galaxy clustering probes. In the paper, which represents a summary of 18 supporting papers, they also present their first results found by combining all four probes — baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), type-Ia supernovae, galaxy clusters, and weak gravitational lensing — as proposed at the inception of DES 25 years ago.

“The methodologies that our team developed form the bedrock of next-generation surveys.”

Alexandra Amon, co-lead of the DES weak lensing working group

“DES really showcases how we can use multiple different measurements from the same sky images. I think that’s very powerful,” said Martin Crocce, research associate professor at the Institute for Space Science in Barcelona and co-coordinator of the analysis. “This is the only time it has been done in the current generation of dark energy experiments.”

The analysis yielded new, tighter constraints that narrow down the possible models for how the universe behaves. These constraints are more than twice as strong as those from past DES analyses, while remaining consistent with previous DES results.

“There’s something very exciting about pulling the different cosmological probes together,” said Chihway Chang, associate professor at the University of Chicago and co-chair of the DES science committee. “It’s quite unique to DES that we have the expertise to do this.”

How to measure dark energy

About a century ago, astronomers noticed that distant galaxies appeared to be moving away from us. In fact, the farther away a galaxy is, the faster it recedes. This provided the first key evidence that the universe is expanding. But since the universe is permeated by gravity, a force that pulls matter together, astronomers expected the expansion would slow down over time.

Then, in 1998, two independent teams of cosmologists used distant supernovae to discover that the universe’s expansion is accelerating rather than slowing. To explain these observations, they proposed a new kind of energy that is responsible for driving the universe’s accelerated expansion: dark energy. Astrophysicists now believe dark energy makes up about 70% of the mass-energy density of the universe. Yet, we still know very little about it.

In the following years, scientists began devising experiments to study dark energy, including the Dark Energy Survey. Today, DES is an international collaboration of over 400 astrophysicists and scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries. Led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, the DES collaboration also includes scientists from U.S. universities, NSF NOIRLab and DOE national laboratories Argonne, Lawrence Berkeley and SLAC.

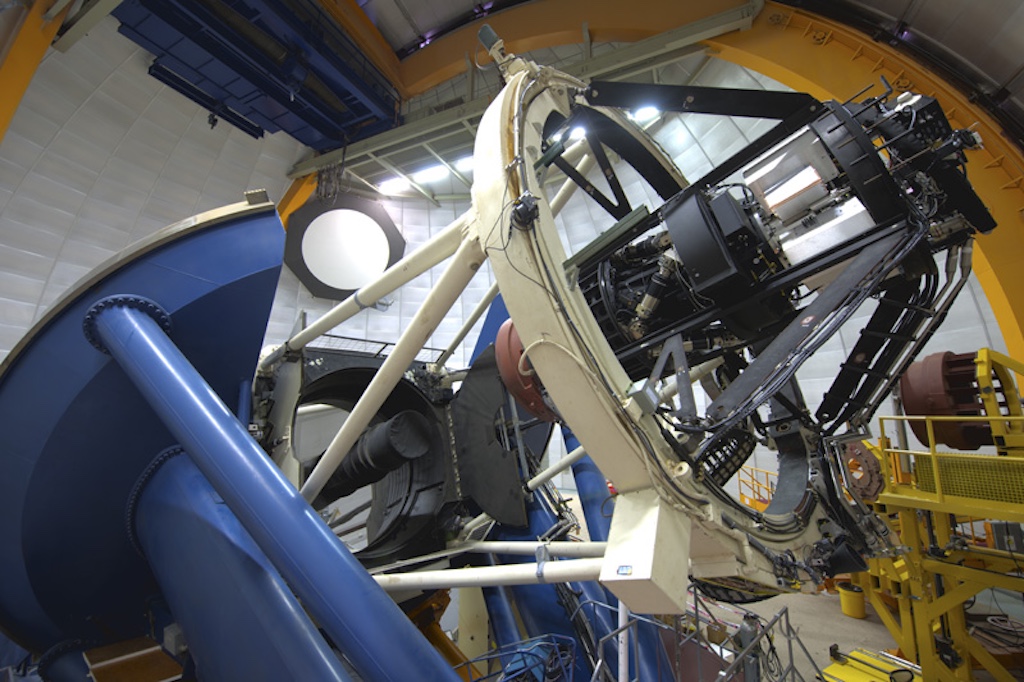

To study dark energy, the DES collaboration carried out a deep, wide-area survey of the sky from 2013 to 2019. Fermilab built an extremely sensitive 570-megapixel digital camera, DECam, and installed it on the U.S. National Science Foundation Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter telescope at NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a Program of NSF NOIRLab, in the Chilean Andes. For 758 nights over six years, the DES collaboration recorded information from 669 million galaxies that are billions of light-years from Earth, covering an eighth of the sky.

For the latest results, DES scientists greatly advanced methods using weak lensing to robustly reconstruct the distribution of matter in the universe. They did this by measuring the probability of two galaxies being a certain distance apart and the probability that they are also distorted similarly by weak lensing. By reconstructing the matter distribution over 6 billion years of cosmic history, these measurements of weak lensing and galaxy distribution tell scientists how much dark energy and dark matter there is at each moment.

“One of the most exciting parts of the final DES analysis is the advancement in calibrating the data,” said Alexandra Amon, co-lead of the DES weak lensing working group and assistant professor of astrophysics at Princeton University. “The methodologies that our team developed form the bedrock of next-generation surveys.”

In this analysis, DES tested their data against two models of the universe: the currently accepted standard model of cosmology — Lambda cold dark matter (ΛCDM) — in which the dark energy density is constant, and an extended model in which the dark energy density evolves over time — wCDM.

DES found that their data mostly aligned with the standard model of cosmology. Their data also fit the evolving dark energy model, but no better than they fit the standard model.

However, one parameter is still off. Based on measurements of the early universe, both the standard and evolving dark energy models predict how matter in the universe clusters at later times — times probed by surveys like DES. In previous analyses, galaxy clustering was found to be different from what was predicted. When DES added the most recent data, that gap widened, but not yet to the point of certainty that the standard model of cosmology is incorrect. The difference persisted even when DES combined their data with those of other experiments.

“What we are finding is that both the standard model and evolving dark energy model fit the early and late universe observations well, but not perfectly,” said Judit Prat, co-lead of the DES weak lensing working group and the Nordita Fellow at the Stockholm University and the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden.

Paving the way

Next, DES will combine this work with the most recent constraints from other dark energy experiments to investigate alternative gravity and dark energy models. This analysis is also important because it paves the way for the new NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, to do similar work with its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

“The measurements will get tighter and tighter in only a few years,” said Anna Porredon, co-lead of the DES Large Scale Structure working group and senior fellow at the Center for Energy, Environmental and Technological Research (CIEMAT) in Madrid. “We have added a significant step in precision, but all these measurements are going to improve much more with new observations from Rubin Observatory and other telescopes. It’s exciting that we will probably have some of the answers about dark energy in the next 10 years.”

More information on the DES collaboration and the funding for this project can be found on the DES website.

The Dark Energy Survey is jointly supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

A lot can happen in the blink of an eye. In a laboratory setting, it takes an average person about one-fifth of a second to see a light and press a button, and in that same interval a hummingbird could beat its wings about a dozen times. Meanwhile, in that same fraction of a second, specialized computer hardware analyzing particle collider data can harness artificial intelligence to make more than 10 million decisions about whether to keep or discard information created by collision events.

“Neural network algorithms help us to gain deeper insights into our data more efficiently to make discoveries much faster than traditional, simple techniques.”

Nhan Tran, head of Fermilab’s AI Coordination Office

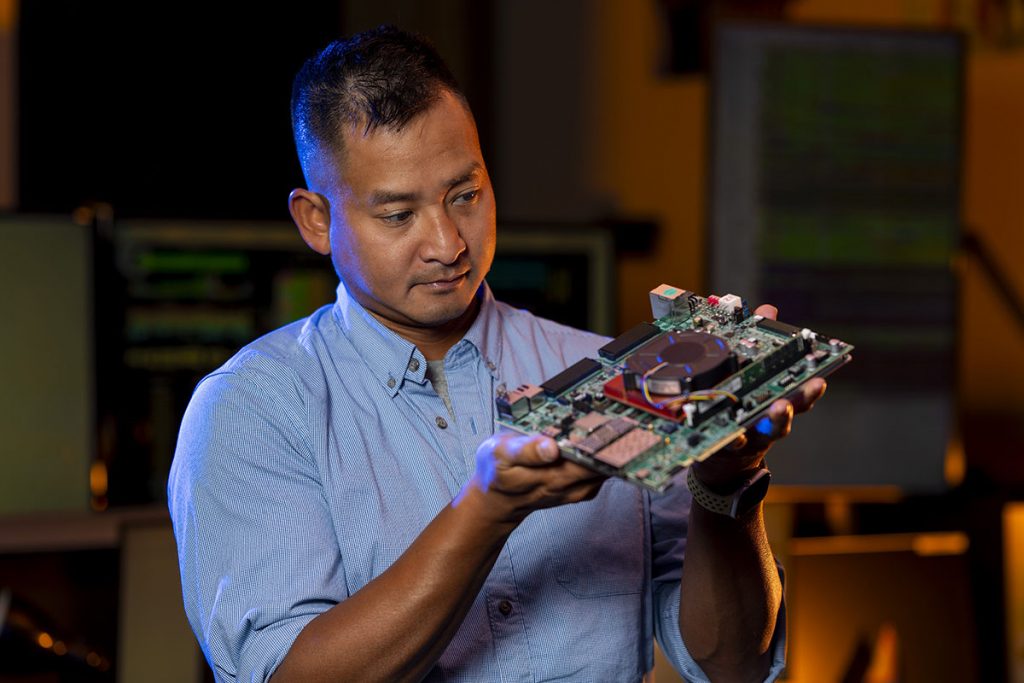

At the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, researchers are pushing the limits of what machines can do, leading an open-source collaboration to embed neural networks directly into physical hardware in the form of efficient, customized digital circuits. Central to this effort is hls4ml, a software framework developed with Fermilab researchers contributing their expertise. Hls4ml can be used to create ultrafast, decision-making hardware for applications ranging from particle physics to fusion science — and beyond.

Humanity’s most ambitious scientific projects, many led by Fermilab or supported by Fermilab researchers, generate staggering amounts of data. Particle collider detectors, such as CMS at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, probe the universe at its most fundamental level. Fermilab is the host laboratory in the U.S. that facilitates participation of hundreds of U.S. physicists from more than 50 institutions in the CMS experiment at CERN.

“The CMS upgrades for the High-Luminosity LHC will produce almost six times more data when it starts running in the 2030s,” said Anadi Canepa, a senior scientist at Fermilab and spokesperson for the international CMS collaboration. “Our updated trigger system will allow us to access more granular information, extended coverage and extended timing information. The challenge is that if we analyze all this extra data, we need to do it fast.”

Neural networks — algorithms inspired by the way the human brain processes information — learn by passing data through interconnected layers, adjusting connections to recognize patterns and make predictions. But learning alone isn’t enough; these networks must also be deployed efficiently to deliver real-world value.

“Neural network algorithms help us to gain deeper insights into our data more efficiently to make discoveries much faster than traditional, simple techniques,” said Nhan Tran, head of Fermilab’s AI Coordination Office.

Once a network is modeled and trained, researchers need a clear path to accelerate it in hardware. That’s where hls4ml comes in.

“Hls4ml takes code for neural networks, which can be written with open-source machine learning libraries like PyTorch and TensorFlow, and essentially turns them into a series of logic gates,” Tran explained.

Traditionally, central processing units, commonly called CPUs, and graphics processing units, or GPUs, found in laptops and desktop computers have been used to perform machine learning algorithms.

“As these methods became more widely used, it was natural to ask whether there was a more efficient approach,” said Giuseppe Di Guglielmo, principal engineer at Fermilab.

By moving neural networks onto specialized hardware such as field-programmable gate arrays and application-specific integrated circuits, researchers can perform many calculations at once and make decisions faster while using less power.

“Even though they are more complicated to program, they let us run sophisticated algorithms in real time, where latency and power matter,” Di Guglielmo added.

Programming these devices traditionally requires deep expertise. With hls4ml, however, preparing decision-making hardware for particle detector triggers becomes attainable to a broader range of researchers.

“The hls4ml team is making the trigger more accessible,” said Canepa. “Anyone who has a new idea can now write an algorithm for the trigger and run it. Hls4ml is absolutely critical to the success of the CMS upgrade, because we will collect an unprecedented, very large and complex data set. Without a capable trigger system to select events, we would not be able to store the most interesting collisions.”

“Many fields of cutting-edge science confront big data challenges and explore the nature of the universe at very short timescales, so research communities ranging from fusion energy to neuroscience and materials science are very interested in what we’re doing to enable new capabilities through the power of AI,” added Tran.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

How do you contain over 15,000 tons of a liquid that must be kept at minus 303 degrees Fahrenheit for a science experiment? A science fiction author might send it up to outer space in a fancy tin can since it’s very cold there and everything is weightless. The Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, a nonfictional experiment with detectors that will be immersed in huge baths of cryogenic liquid argon, is going the opposite direction — down.

“By going underground, the DUNE detectors in South Dakota will significantly reduce cosmic backgrounds.”

Vincent Basque, Fermilab researcher

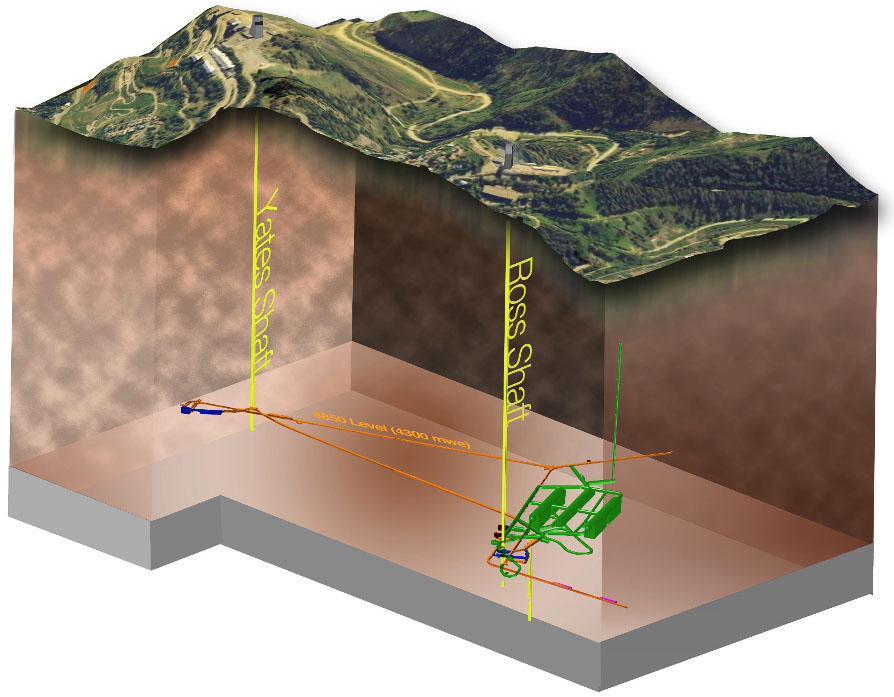

DUNE is the most sensitive experiment ever conceived for learning about the origins of the universe from the properties of neutrinos, among the first particles to be emitted by the Big Bang. The experiment needs to shield its particle detectors from the cosmic rays that constantly jet through space and bombard the Earth, lest they overwhelm and mask the relatively faint signals the experiment aims to capture. So DUNE researchers will build and run these detectors at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, South Dakota, underneath a mile of earth that will absorb most of the cosmic traffic.

“By going underground, the DUNE detectors in South Dakota will significantly reduce cosmic backgrounds,” said Fermilab postdoctoral researcher Vincent Basque. “This allows us to study neutrinos sent from the Fermilab beam in Illinois with high precision, detect neutrinos from astrophysical sources like the sun or a nearby supernova, and search for other extremely rare processes.”

The DUNE collaboration — hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory — is currently preparing to install two of these multi-kiloton detector modules using variants of liquid-argon time projection chamber, or LArTPC, technology. International collaborators hope to contribute an additional two modules in coming years. Each module will be housed in an insulating container called a cryostat that is nearly 500,000 cubic feet in size — roughly the same volume as five Olympic-size swimming pools. Far from being available at your local hardware store, CERN has contracted with GTT, a company that designs cryostats for shipping liquefied natural gas, to design the cryostats. GTT has been designing smaller cryostats for CERN experiments since 2007. CERN, the largest European center for nuclear research that is collaborating on DUNE, is contributing the cryostats for the experiment.

Cryostats for liquid-argon time projection chambers must be robust enough to resist the outward pressure of the fluid (1.4 times denser than water) and pliant enough to retain their integrity over a roughly 375 degrees Fahrenheit range between room and liquid argon temperatures. They must also be sufficiently insulated to maintain the cryogenic temperature level and able to accommodate an industrial-scale cryogenics system to maintain the required argon purity. Beyond that, CERN will construct the cryostats in place from pieces that fit down a 4-by-6-meter mine shaft.

“Making this possible has required detailed and precise design and logistics planning.”

Lluís Miralles Verge, CERN

“It’s the first time we will do something this big,” said Lluís Miralles Verge, the leader for the experiment’s cryostat project at CERN. “The DUNE LArTPCs will be installed in caverns that can only be reached via a deep shaft. Making this possible has required detailed and precise design and logistics planning.”

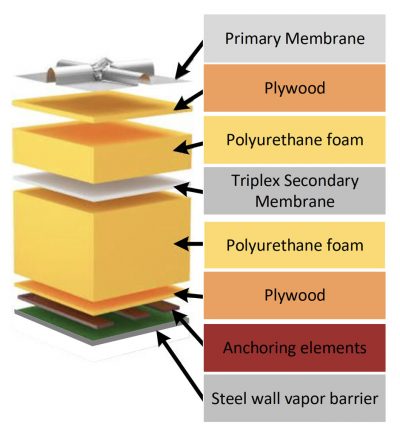

To achieve leakproof liquid and vapor containment, in addition to adequate insulation and support, the DUNE cryostats are composed of several layers. GTT’s tried-and-true design is of a style known as a membrane cryostat, because of the innermost layer that forms a membrane to contain the liquid cryogen. This layer, and all the others, come down the shaft in pieces and are assembled in the detector cavern, starting with the outer structure. Completion of the inner portions of a DUNE cryostat requires more than 5,000 individual pieces.

The primary and innermost layer is constructed of stainless steel, a material that doesn’t exude anything that could contaminate the argon. The corrugated sections are welded together to form the leakproof membrane that is in direct contact with the liquid argon.

Why the corrugations? They are important for mitigating the contraction effects in both dimensions on the metal as it cools to its final cryogenic temperature. Without them, the cryostat’s length would shrink by an impressive 20 inches or so, and burst the welds. Instead, each corrugation changes shape very slightly and the welds hold. Controlling the membrane contraction also, and importantly, helps keep the detector precisely in position.

“The DUNE prototypes at CERN have been invaluable,” said David Montanari, cryogenics project manager for DUNE. “They have demonstrated that the detector elements, cryostats and cryogenics work together properly, giving us confidence that the DUNE far detector cryostats will perform flawlessly.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

A groundbreaking experiment at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, which will probe a narrow, previously unexplored region of mass where some scientists believe dark matter lurks, is one step closer to taking experimental data.

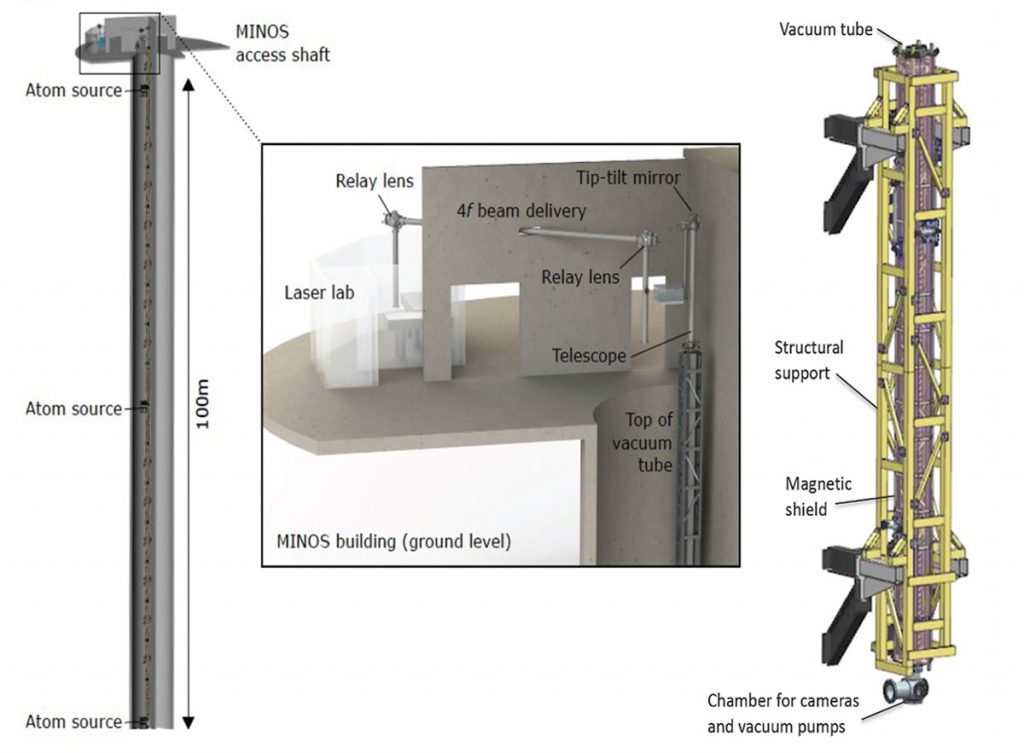

The Matter-wave Atomic Gradiometer Interferometric Sensor experiment — also called MAGIS-100 — is a collaboration that also includes Stanford University, Northwestern University and eight other research institutions in the U.S. and the U.K. The interferometer will occupy a 100-meter shaft at Fermilab used years ago for accessing underground experiments. Once constructed, MAGIS-100 will be the world’s largest vertical atom interferometer.

The project has reached an important milestone — construction is complete on a laser lab that will contain the infrastructure to generate high-power laser beams used to operate the interferometer. Construction began in 2023.

“Finishing the laser lab marks completion of our first major project construction.”

Jim Kowalkowski, MAGIS-100 project manager

“Finishing the laser lab marks completion of our first major project construction,” said Jim Kowalkowski, MAGIS-100 project manager. “Now we’re moving experimental equipment into the laser lab; we’re doing a lot of testing; we’re characterizing different components to understand any problems and correct them if we can. A lot has to happen.”

In the experiment, strontium atom clouds colder than outer space will be dropped into the 100-meter shaft enclosing the interferometer. Carefully timed laser pulses work like beam splitters and mirrors for the atoms, splitting each cloud into two separate paths and then bringing them back together. Similar to what occurs when two rocks are thrown into a pool and the waves interfere with each other, any disturbance in one path will show up as an interference pattern on a camera lens.

The interferometer will be incredibly precise, capable of detecting extremely small changes in gravitational fields that could detect difficult-to-observe phenomena, such as the presence of dark matter or gravitational waves. Scientists hope to use it to tease out ultralight dark matter by stimulating interactions between theorized particles of dark matter (axions), and regular matter (electrons or light). But before the experiment can begin to discover new physics phenomena, there is much work to do. The research team must now begin to set up and test the intricate laser systems that will feed the rest of the experiment.

The making of the world’s largest interferometer

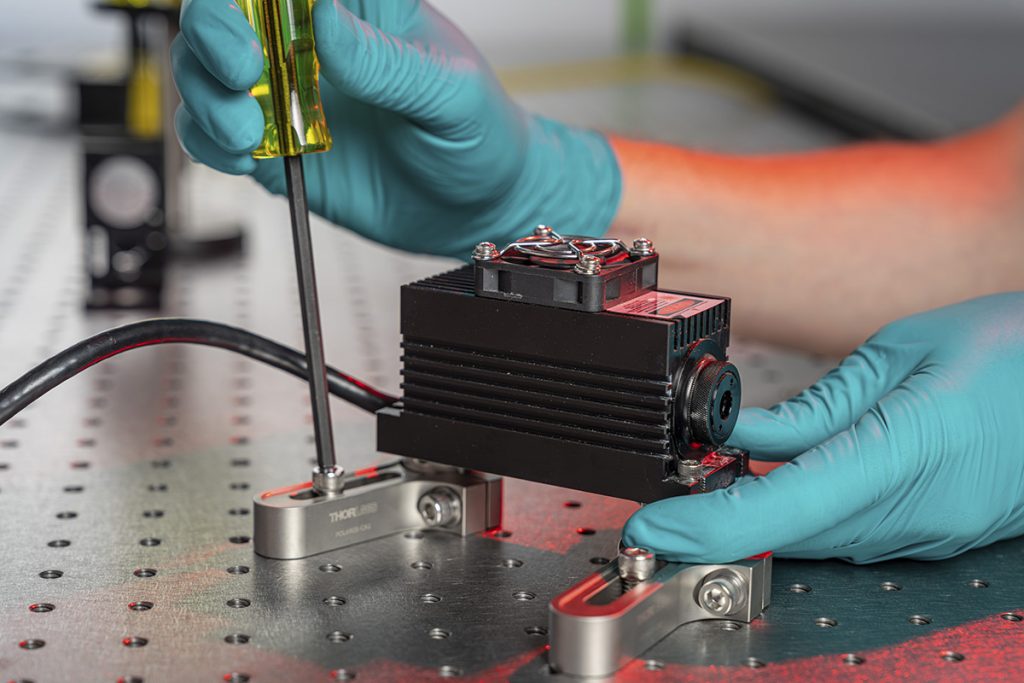

The laser lab is fully enclosed to prevent light leakage, and a sophisticated laser safety interlock system is being built to control access to the room to prevent any accidental exposure. Before it can operate, Fermilab must certify the interlock system meets national laser safety criteria.

A sturdy tower redirects a tuned laser beam from optical tables that hold the main laser system to a transport tube running to the shaft that will hold a vertically mounted interferometer. Here, an optical telescope redirects and focuses the laser light so it is the right size and position to interact with the strontium atoms, all contained within a vacuum.

Three atom sources, being constructed by a group at Stanford University, will be placed at the top, middle and bottom of the interferometer. These devices will produce strontium atom clouds near absolute zero —negative 273.15 degrees Celsius. Special electrical fields will shuttle these clouds to an area where they are thrown upward and allowed to fall the length of the shaft. From there, the interferometry beams from the laser lab, directed by special timing systems, will take over, striking the clouds and causing them to split and rejoin the paths of the free-falling atoms. Imaging cameras throughout the interferometer will be used to record their behavior.

Considering the optics

Now the painstaking process to study and characterize the full experiment environment begins. A team led by Tim Kovachy from Northwestern University is leading exploration into how each component is affected by outside sources — for example, how vibrations from the ground and building equipment contribute to fluctuations in the laser beam trajectory.

“The alignment of each component must be extremely accurate.”

Dylan Temples, MAGIS-100 researcher

“The alignment of each component must be extremely accurate,” said Dylan Temples, a researcher at Fermilab who works on MAGIS-100. “Even small vibrations or strain in the table on which the elements are set up might lead to noise or interference that could seriously impact the experiment.”

The team must ensure any interesting signals they observe are correctly attributed to actual physics phenomena, not from unknown sources that can masquerade as good observations. In addition, knowing about these unexpected negative effects allows them to adjust, ensuring everything is properly aligned and works as expected before the experiment runs.

“We have already made initial measurements of the mechanical resonances of the tower in the laser lab, which inform us how the tower will respond to vibrations,” said Kovachy.

In parallel to optics system testing, researchers are starting to test the 17-foot sections that will comprise the 100-meter vacuum tower, within which the vacuum pressure is extremely low, similar to that on the moon. Each section must be magnetically and electromagnetically insulated to prevent environmental signal interference. The welding process for the stainless-steel sheets used for the vacuum tubes can magnetize material along the seam, creating potential noise that could alter measurements during the experiment. Researchers use special measuring devices to locate these unwanted magnetic fields.

As the laser lab setup continues over the next year, construction will begin to prepare the shaft for installations of the vacuum tube sections and atom sources. Plans are to deliver the atom sources Stanford University is building in late 2026 and install them, along with the vacuum tube modules in 2027.

Installation of the MAGIS-100 experiment is currently on track to conclude at the end of 2027, along with some early data-taking. Commissioning is planned to begin in 2028.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

The MAGIS-100 project is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy. Collaborator funding is supplied through grants from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the U.K. Research and Innovation.

Groundbreaking work by a joint team from the Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center, hosted at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, and NYU Langone Health was recognized as one of the top 10 submissions in the National Institutes of Health Quantum Computing Challenge.

The team, called QuantuMRI, developed a quantum algorithm to simulate how human tissue responds during MRI scans, paving the way for more accurate and efficient medical imaging technologies. QuantuMRI received a $10,000 award and advanced to the challenge’s second phase, where finalists will further test and demonstrate their solutions for clinical and biomedical use cases.

“This achievement reflects the kind of innovation we aim to foster through DOE-supported quantum research.”

Zachary Goff-Eldredge, program manager in DOE Office of High Energy Physics

“It’s inspiring to see a team like Fermilab-NYU bring bold, cross-disciplinary thinking to such an important area of biomedical research,” said Zachary Goff-Eldredge, program manager in the Department of Energy’s Office of High Energy Physics. “This achievement reflects the kind of innovation we aim to foster through DOE-supported quantum research. I’m excited to see how their work continues to evolve throughout the NIH challenge and how it might ultimately shape the future of medical imaging.”

MRI scans offer detailed, non-invasive views of soft tissues for medical diagnoses. The technology relies on intrinsic magnetic moments that atoms in the human tissues possess. These atoms interact with an external magnetic field and enable the detection of local features of the tissue.

Quantitative MRI, or qMRI, goes a step further by measuring how the relaxation times of the local magnetic moments are influenced by biophysical tissue properties — offering clinicians deeper insights into subtle changes in tissue composition and making it easier to detect and characterize changes that may not be visible with traditional methods.

The challenge? Simulating these complex tissue behaviors requires significant computational resources as researchers aim for greater resolution and accuracy. The Fermilab-NYU team aims to leverage quantum computing to advance qMRI by enabling fast, high-resolution estimates of multiple tissue properties that are highly accurate and reproducible.

“The collaboration between Fermilab and NYU Langone is a perfect example of how quantum computing can be applied to real-world challenges with meaningful impact,” said Riccardo Lattanzi, professor of radiology and director of the Center for Biomedical Imaging at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “This project highlights the potential for quantum technologies to transform medical imaging and accelerate the clinical translation of qMRI, helping doctors make better decisions and moving us closer to precise, personalized medicine.”

NYU first joined the SQMS collaboration in 2022 with a plan to explore a new method for analyzing MRI scans. The collaboration reflects a growing interdisciplinary effort to bridge physics, computer science, and medicine — combining the SQMS Center’s expertise in quantum systems with NYU Langone’s clinical insight and leadership in imaging research.

As the NIH challenge continues, the Fermilab-NYU team will build on this early success, aiming to deliver scalable, high-resolution and reproducible qMRI tools that could ultimately enhance patient care and diagnostics across a wide range of conditions. Currently, the team is engaged in the second stage of the competition. The NIH Quantum Computing Challenge concludes in the fall of 2027.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

The Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center at Fermilab is supported by the

DOE Office of Science.

The Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center is one of the five U.S. Department of Energy National Quantum Information Science Research Centers. Led by Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, SQMS is a collaboration of more than 40 partner institutions — national labs, academia and industry — working together to bring transformational advances in the field of quantum information science. The center leverages Fermilab’s expertise in building complex particle accelerators to engineer multiqubit quantum processor platforms based on state-of-the-art qubits and superconducting technologies. For more information, please visit www.sqmscenter.fnal.gov.