The Department of Energy’s Office of High Energy Physics recommitted $8 million to fund Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory’s job retention program that provides opportunities for U.S. military veterans. The recommitted funding over five years (fiscal years 2026-2030) is a substantial increase from the $2.35 million the office awarded for FY 2022-2025.

The Veteran Applied Laboratory Occupational Retraining program provides training and career opportunities to military veterans at the start of their civilian careers. This includes valuable hands-on training experiences and full-time technical career placement and security at Fermilab.

“The Department of Energy continues to support our nation’s veterans by recommitting to the VALOR program. The cutting-edge training and education veterans receive during their service, along with their commitment to teamwork, is a great transition to technical positions at the national labs,” said Gina Rameika, Associate Director of Science for High Energy Physics at the Department of Energy.

The program expands opportunities for military veterans by providing multiple entry points for STEM-based technical learning and training that lead to consideration for full-time employment. Military veterans are offered 10-week paid internships and 6-month paid apprenticeships in a broad range of laboratory specializations that include, but are not limited to, fabricating, assembling, calibrating, operating, testing, repairing or modifying electronic or mechanical equipment, systems, devices and databases. Opportunities also exist to work in information technology, procurement, and in environmental, safety and health.

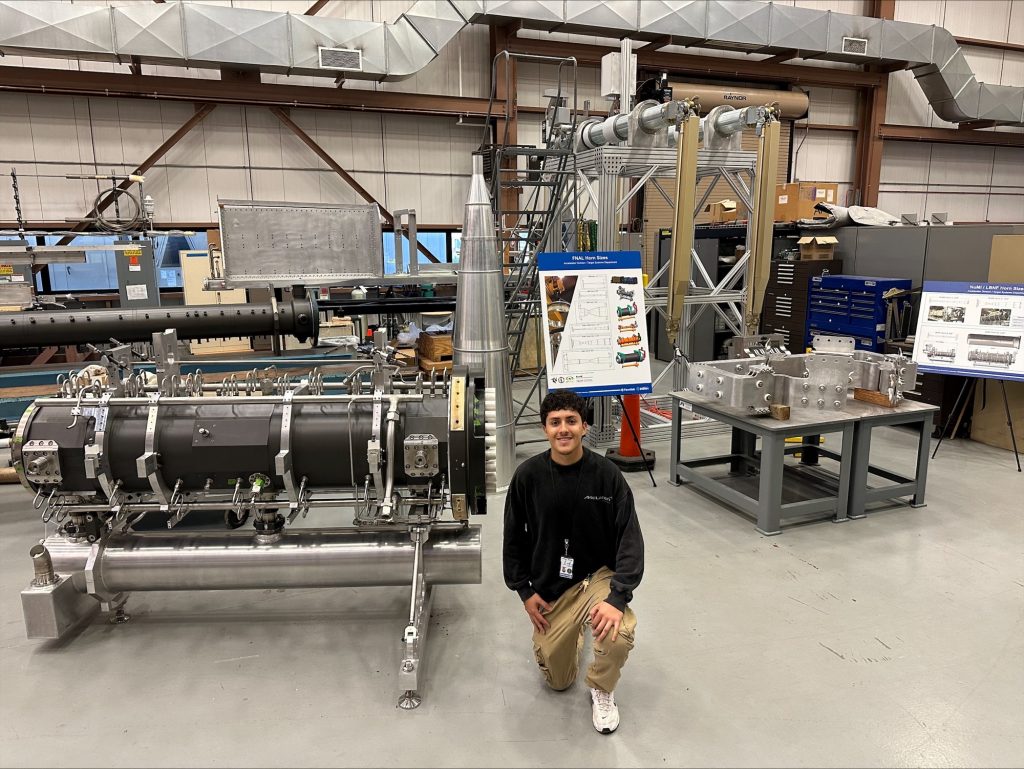

“The VALOR program was an incredible opportunity that helped me grow both professionally and personally,” said Anthony Ramirez. “Coming from an NJROTC background at East Aurora High School, I value structure, discipline, and teamwork. These qualities aligned well with Fermilab’s collaborative environment. I gained hands-on technical experience, mentorship and a clear direction for my future in STEM.”

Ramirez now works as a mechanical technician in the Accelerator Target Systems Division and is attending Waubonsee Community College with aspirations of becoming a mechanical engineer.

As an expanded way of reaching cadets and veterans early in their careers, Fermilab began reaching out to local high school ROTC cadets in 2022 to promote and amplify learning and career opportunities through multi-year summer internship experiences at the lab.

“Fermilab has a successful record of providing opportunities for military veterans and cadets and retaining them as full-time employees,” said Sandra Charles, Director of Workforce Pathways and Partnerships. “From 2022 to 2025, we hired 22 participants of the VALOR program. We are grateful to DOE for their continued support of this important program and look forward to expanding the success of VALOR in the coming years.”

For more information on VALOR, visit internships.fnal.gov/valor/

Interested parties are encouraged to apply at Fermilab jobs.

Launched in 2022, VALOR expanded Fermilab’s established VetTech internship program (initiated in 2016), deepening its commitment to U.S. military veterans. VALOR has since distinguished itself as a leader in workforce development, earning the HIRE Vets Gold Medallion Award from the U.S. Department of Labor in both 2019 (as VetTech) and 2024. This consistent recognition underscores VALOR’s effectiveness as a model for recruiting, training, hiring, and retaining military veterans and transitioning service members entering the civilian workforce. By leveraging veterans’ advanced technical skills and leadership experience, the program significantly contributes to Fermilab’s ability to address critical workforce challenges, including attrition, succession planning and the need for emerging technical talent. The high conversion rate of VALOR participants into long-term, high-impact roles within the laboratory amplifies the program’s strategic value, demonstrating the efficacy of veteran-centered pathways in meeting workforce and innovation goals.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

Editor’s note: This press release was originally published by the University of Chicago.

Norbert Holtkamp has been appointed as the new director of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, effective Jan. 12, 2026.

Holtkamp brings deep scientific and operational expertise to Fermilab, which is the premier particle physics and accelerator laboratory in the United States. He is the former deputy director of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University and currently serves as a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, advocating for robust international scientific collaboration. He is also currently a professor of particle physics and astrophysics and of photon science at SLAC and Stanford.

University of Chicago President Paul Alivisatos made the announcement Dec. 15 in his capacity as chair of the board of directors of Fermi Forward Discovery Group, LLC, which operates the laboratory for the U.S. Department of Energy and whose partners include the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association.

“We’re excited to welcome Norbert, who brings a wealth of scientific and managerial experience to Fermilab,” Alivisatos said. “He will champion Fermilab’s mission of pioneering scientific discovery, help ensure the success of projects critical to the lab’s future and strengthen the relationships necessary for shared achievements and inspire the next generation of researchers.”

Holtkamp has managed large scientific projects throughout his career — experience that will be critical as Fermilab continues to advance the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (LBNF/DUNE) among other ambitious projects. During his tenure at SLAC, he managed the construction of the Linac Coherent Light Source upgrade (LCLS-II), the world’s most powerful X-ray laser, along with more than $2 billion of on-site construction projects. He previously served as the principal deputy director general for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a multinational organization working to achieve fusion power at power plant scale.

Holtkamp is deeply familiar with Fermilab, having worked there from 1998 to 2001. During that time, he participated in the commissioning of the Main Injector — the lab’s most powerful particle accelerator — and also led a multi-laboratory study on the feasibility of an intense neutrino source based on a muon storage ring.

In his new role, Holtkamp will continue Fermilab’s work to modernize its operations and infrastructure to leverage the capabilities of LBNF/DUNE — the largest experiment in lab history — and other major projects.

“I am deeply honored to have been selected as the next director of Fermilab,” Holtkamp said. “Fermilab has done so much to advance our collective understanding of the fundamentals of our universe. I am committed to ensuring the laboratory remains the neutrino capital of America, and the world, and the safe and successful completion of LBNF/DUNE is key to that goal. I’m excited to rejoin Fermilab at this pivotal moment to guide this project and our other important modernization efforts to prepare the lab for a bright future.”

Holtkamp holds the equivalent of a master’s degree in physics from the University of Berlin and a Ph.D. in physics from the Technical University in Darmstadt, Germany.

Holtkamp’s appointment follows an extensive search by a panel of distinguished scientific and organizational experts. The search committee, which included prominent leaders from the laboratory’s critical stakeholders, was chaired by Argonne National Laboratory Director Paul Kearns and Vice-Chair CERN Director-General Designate Mark Thomson.

Holtkamp succeeds University of Chicago Professor Young-Kee Kim, who has served as interim director since January 2025. Alivisatos expressed his gratitude for Kim’s “tireless service” as director.

“We asked Young-Kee to lead the laboratory for one year, and she immediately devoted her talent, leadership and boundless enthusiasm to aid the lab during a time of transition,” Alivisatos said. “Young-Kee played a critical role in strengthening relationships with Fermilab’s leading stakeholders, driving the lab’s modernization efforts, and positioning Fermilab to amplify DOE’s broader goals in areas like quantum science and AI.”

A 6,800-acre facility headquartered in Batavia, Ill., Fermilab aims to shed new light on the understanding of the universe — from the smallest building blocks of matter to the deepest secrets of dark matter and dark energy. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov to learn more.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

Ten years ago, the first neutrinos interacted in the liquid argon of the MicroBooNE particle detector at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, marking a turning point for the lab’s neutrino research program. MicroBooNE is celebrating its tenth anniversary as part of a vibrant program of liquid-argon-based neutrino experiments, including the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment — an international collaboration hosted by Fermilab that is on track to becoming the biggest liquid-argon detector ever built and a focal point of particle physics research.

“Liquid argon offered the promise to solve the dual challenges of imaging neutrino interactions with millimeter precision and doing that at the kiloton scale needed to answer big science questions.”

Matthew Toups, Fermilab senior scientist and co-spokesperson of MicroBooNE

In October of 2015, the scientists of the MicroBooNE collaboration were excited about the potential of liquid argon to transform neutrino physics.

“Liquid argon offered the promise to solve the dual challenges of imaging neutrino interactions with millimeter precision and doing that at the kiloton scale needed to answer big science questions,” said Matthew Toups, Fermilab senior scientist and co-spokesperson of MicroBooNE.

Those big questions, the origin of matter in our universe and the unification of forces into a Grand Unified Theory, now lie at the heart of DUNE’s science program. But in 2015, it was not yet clear whether liquid-argon technology was advanced enough to support the future of U.S. neutrino physics research.

“The liquid-argon time projection chamber had been proposed in the 1970s,” said Toups. Projects like ICARUS at Gran Sasso and ArgoNeuT at Fermilab had shown how powerful it could be, but what we wanted to do with MicroBooNE was to show that a large-scale liquid-argon detector could operate for multiple years and deliver a broad physics program.”

The MicroBooNE collaboration achieved this ambitious goal. The detector operated for six years, and the collaboration, to date, has released over 80 scientific publications. More than 70 PhD students have completed their degrees through their work on MicroBooNE, and MicroBooNE’s science output is showing no signs of slowing.

Argon, an inert element, becomes liquid at around minus 303 degrees Fahrenheit. The third most common element in the atmosphere, it is relatively inexpensive to liquify in large amounts, making it ideal for experiments designed to detect neutrino interactions. Inside a liquid-argon-based detector, charged particles from neutrino interactions strip electrons from argon atoms as they pass by, and an electric field draws those electrons to sensing wire planes where the interaction can be recorded and reconstructed in exquisite detail.

The capability that liquid argon brings to particle identification has enabled MicroBooNE to deliver an impressive program of searches for physics beyond the Standard Model. Foremost is the search for the sterile neutrino — a new type of neutrino that, while completely invisible to detectors, could cause the appearance of electron neutrinos in Fermilab’s Booster Neutrino Beam. MicroBooNE has been able to identify much purer samples of electron neutrinos than previous experiments, placing strong limits on the simplest sterile-neutrino models and guiding neutrino researchers to explore a more expansive, sophisticated range of models to explain the neutrino’s many puzzles. But MicroBooNE’s program of new-physics searches has gone far beyond that, probing phenomena that could reveal new particles or forces in “dark sectors,” which might help explain the dark matter in our universe thought to provide the mass necessary to hold galaxies together.

MicroBooNE has also produced a wealth of new measurements describing how neutrinos interact with nuclei.

“Precision neutrino physics starts with understanding how neutrinos interact with the nuclear target,” said MicroBooNE collaborator Elena Gramellini of the University of Manchester. “Building on the lessons learned from ArgoNeuT, MicroBooNE pioneered techniques to unravel how neutrinos interact with argon’s complex nucleus, producing a remarkable set of measurements that capture the subtle nuclear physics at play. MicroBooNE’s rich set of results is now a treasure trove of data shaping the models that DUNE will rely on to deliver its physics goals.”

Another of MicroBooNE’s contributions to neutrino research is the people who comprise the collaboration.

“The community of pioneering researchers that MicroBooNE has fostered is the foundation of the Fermilab neutrino program.”

Bonnie Fleming, founding MicroBooNE spokesperson and Fermilab chief research officer

“The talent and dedication of the early-career researchers who have made seminal contributions to MicroBooNE’s physics is amazing,” said Bonnie Fleming, founding spokesperson of MicroBooNE and chief research officer at Fermilab. “Many of the current leaders of our field developed their skills as part of MicroBooNE. The community of pioneering researchers that MicroBooNE has fostered is the foundation of the Fermilab neutrino program. We wouldn’t be where we are today had MicroBooNE not demonstrated the power of liquid argon and provided a training ground for so many students and postdocs.”

MicroBooNE is now joined by the Short-Baseline Neutrino Detector and ICARUS experiments that comprise the Fermilab Short-Baseline Neutrino Program. Together, they will open new windows onto the intriguing physics behind nature’s most elusive particle. And the DUNE experiment, poised to take data in only a few years’ time, will use liquid argon to shine light on science’s biggest questions. From those first few interactions recorded in 2015 has grown an international science program, bringing more than 1,000 scientists together to expand the boundaries of human knowledge.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.