What makes for a good dark matter detector? It has a lot in common with a good teleconference setup: You need a sensitive microphone and a quiet room.

Scientists working on the SENSEI experiment at the Department of Energy’s Fermilab now have demonstrated for the first time a particle detector — based on charge-coupled device, or CCD, technology — with both the sensitivity and reduced background rates needed for an effective search for low-mass particles of dark matter, the mysterious substance that accounts for about 80 percent of all matter in the universe.

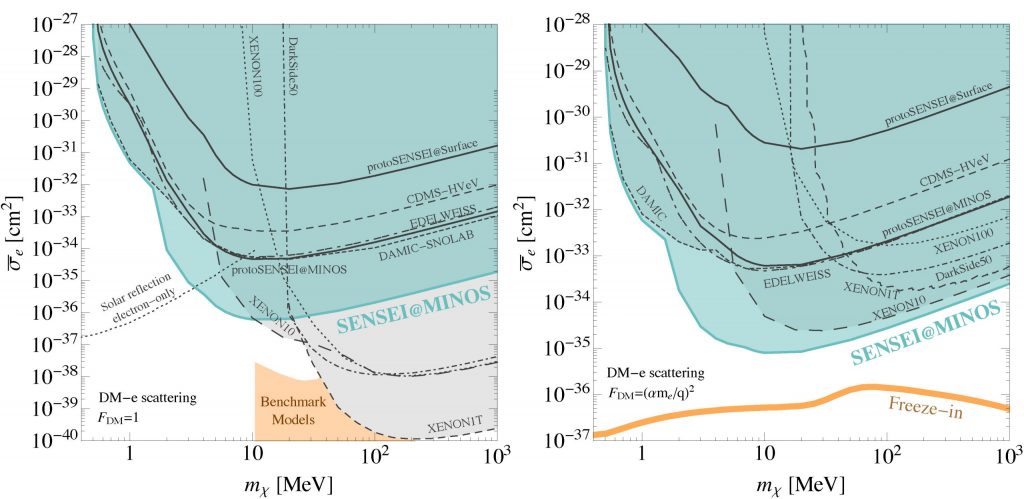

The demonstration is important in two ways. First, the background rates measured by the SENSEI detector are record lows for a silicon detector. They set the world’s strongest limits on dark matter interactions with electrons, across a wide range of models. Second, it shows the high quality of the detectors that will be used in the full-scale SENSEI experiment under construction. SENSEI will run at the Canadian SNOLAB deep underground laboratory.

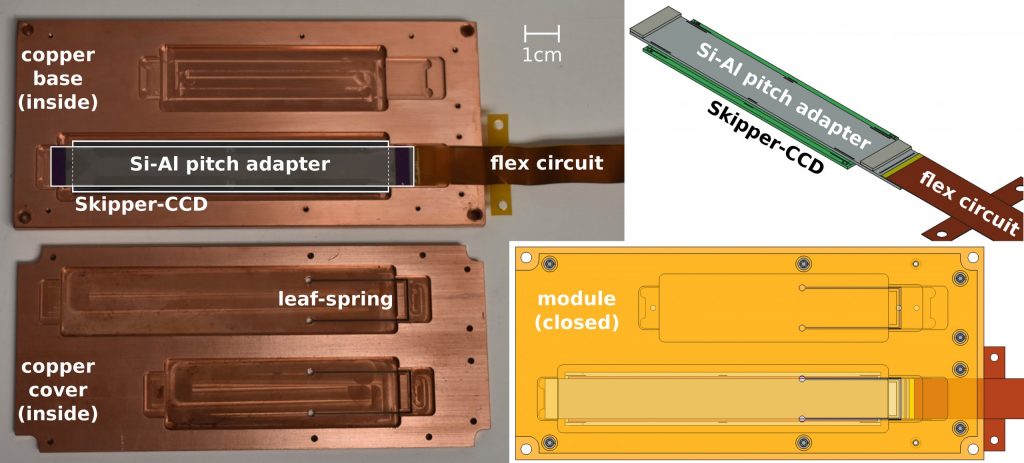

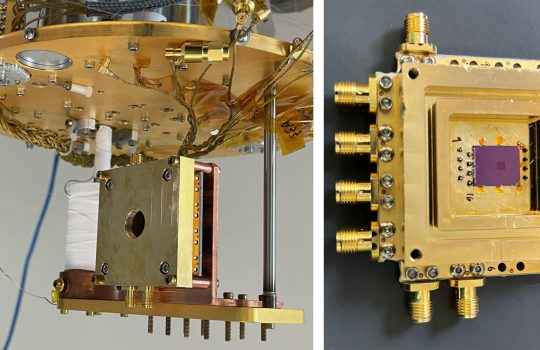

The SENSEI detector is a 5.4-megapixel CCD made of 2 grams of silicon currently operating about 100 meters underground at Fermilab. If a dark matter particle collides with one of the electrons in the silicon, the energy transferred to the electron may be enough to liberate it from the crystal structure of the silicon. If there is enough energy, additional electrons will be freed. This charge is the signal SENSEI scientists are looking for. The smaller the signal SENSEI can detect, the broader the range of dark matter models it can test.

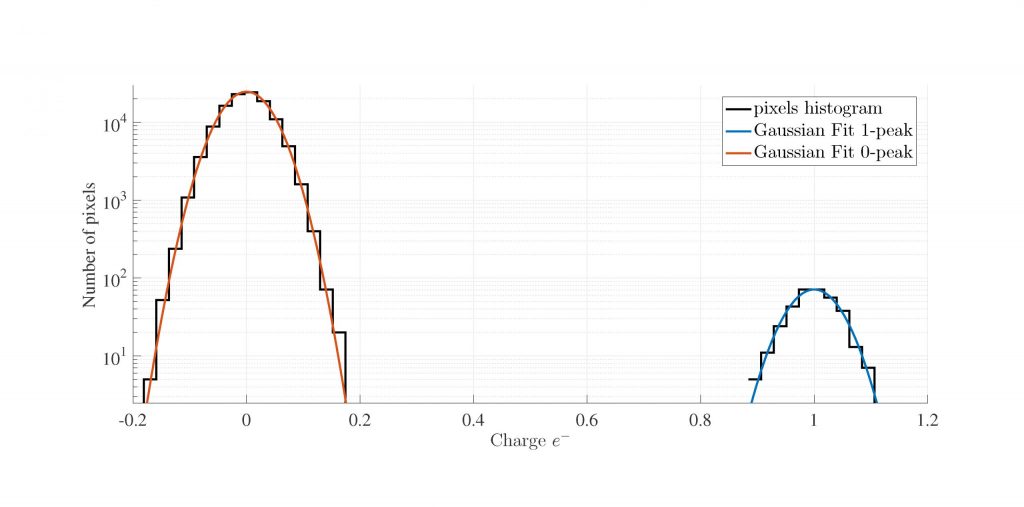

To observe small dark matter signals, the first thing scientists need is a sensitive detector. In other words, they must be able to detect a small signal and consistently distinguish it from a truly empty detector. As demonstrated in previous work, SENSEI’s skipper-CCDs, designed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, can count the exact number of electrons in each pixel.

In this test data, taken with a very long acquisition time, we plotted the measured charge in each pixel. The true charge is of course always an integer number of electrons. The measurement precision is a small fraction of an electron, so the 0-electron and 1-electron pixels are well separated, and there is no possibility of miscategorizing an empty pixel. Image: SENSEI collaboration

Second, scientists need low background — the rate of signal-like events from causes other than dark matter has to be small. A sensitive detector with high background is like a studio microphone in a noisy room. Even if the microphone can pick up a whisper, your soft voice might be drowned out by the noise of the washing machine in the background. The only way to improve the recording is to eliminate the noise of the washing machine.

The SENSEI collaboration now has demonstrated for the first time that it has a sensitive dark matter detector and can reduce background rates. It’s important to demonstrate that a detector can achieve low background rates before you scale up to a larger experiment with the same technology, because otherwise you are just going to scale up your background rate. Previous dark matter searches by SENSEI used prototype CCDs, which had high sensitivity but also high backgrounds because they were not made with the highest-quality silicon.

SENSEI rules out the blue regions, where the rate of dark matter interactions would be larger than the event rate that SENSEI observes.

Gray regions are ruled out by other experiments. The orange bands are favored by theoretical models and are targets for the full-scale SENSEI experiment. Image: SENSEI collaboration

SENSEI’s new dark matter search has yielded the first result from its new science-grade CCDs, which were fabricated in a dedicated production run for SENSEI with high-quality silicon. The collaboration also reduced the amount of radiation that hits the CCD by adding extra shielding around the experiment. The result was a decrease in background event rates compared to the previous search with a prototype CCD. The rate of single-electron events decreased from 33,000 to 450 events/gram-day, and we see fewer two-electron events (five, down from 21) in a much larger exposure (2.09 gram-days, up from 0.043). We also see no three- or four-electron events — just as in the previous search, but with a larger exposure.

The science-grade CCDs work as well as could have been hoped, and SENSEI expects background rates to be even lower at SNOLAB. There will likely be more great science from SENSEI in the near future!

Learn more from SENSEI’s preprint or the collaboration’s presentation at a seminar at Fermilab.

Sho Uemura of the SENSEI collaboration is a scientist at Tel Aviv University and is supported in part by the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program.

U.S. work on SENSEI is supported by the DOE Office of Science. This work is also funded by the Heising-Simons Foundation.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.