Nearly a mile belowground in South Dakota, there’s a flurry of activity. Three shifts of 30 construction workers labor around the clock, carving out subterranean space for science. It’s a huge effort centered around one of the tiniest things in nature: the neutrino.

Drilling the ventilation shaft. Fermilab’s Syd Devries (left) and James Rickard stand with the reamer. Photo: Andrew Hardy, Thyssen Mining

Neutrinos are fascinating particles. Trillions of them pass through you every second without a trace. They’re produced by almost everything: Earth, the sun, supernovae, bananas and people, to name a few. These bizarre building blocks could hold the key to understanding why matter exists in the universe, rather than antimatter — or nothing at all.

To better study these elusive particles, an international collaboration of more than 1,000 scientists are building the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, or DUNE, hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Researchers will study a beam of neutrinos as it leaves Fermilab in Illinois and again when it reaches the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. The particles will travel 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) straight through the earth to go from lab to lab — no tunnel needed.

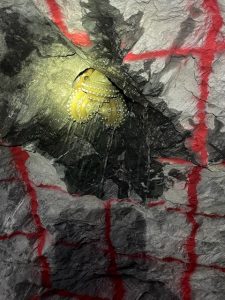

On June 30, the drill head breaks through the roof at the 4,850-foot level to complete the pilot hole for the raise-bore ventilation. Photo: Fermilab

Space for four jumbo jets

The DUNE detector in South Dakota will be the largest neutrino detector of its kind ever made. Each of the four detector modules will hold 17,000 tons of liquid argon, in which neutrinos will interact and leave their signature traces. Making space for these massive instruments and their support equipment is part of the work to create the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility. It will require moving roughly 800,000 tons of rock, creating caverns big enough to hold the bodies of four jumbo jets.

Thyssen Mining, the company carrying out the excavation, is one of two major contractors that are supporting the excavation phase of work.

“It’s our first federal contract. We were interested in it because we do large-cavern excavation in hard rock, so we are well qualified for it,” Andrew Hardy of Thyssen Mining said. “It’s very exciting for us to be part of this massive team that will contribute towards the success of this project. We’re part of a great on-site team.”

Before large-cavern excavation can begin, there is some prep work to do. The first step is widening existing underground tunnels, called drifts, and creating a quarter-mile-long vertical ventilation shaft. The opening will improve the flow of air needed for excavation a mile underground at the 4,850-foot level, where the main construction work will take place. The excavation of the main caverns will begin this fall.

Excavating with precision

To create the shaft, Thyssen is using a technique called “raise-bore drilling.” In June, construction workers drilled a 1,200-foot-long pilot hole about a foot in diameter from the 3,650-foot level down to the 4,850-foot level. The drill bit used sensors called inclinometers to detect any deviation from vertical, sending real-time data to a computer that issued corrections to the steering mechanism. The pilot hole was completed on June 30, with the drill emerging mere inches from its target in the cavern at the 4,850-foot level.

With the pilot hole complete, workers at the 4,850-foot level replaced the drill bit with a large reamer. This circular tool is about 12 feet wide and spins as the construction crew pulls it up through the ceiling, chewing out rock as it goes. The debris falls down to the 4,850-foot level, where it is scooped up, transported to the Ross Shaft and taken for a mile-long ride to the surface. A conveyor system then brings the rock another three-quarters of a mile to a former open-pit mining site called the Open Cut. Crews expect to complete the ventilation shaft in the fall.

The raise-bore technique “is probably the best method to build circular shafts,” said James Rickard, the Fermilab resident engineer managing the excavation. “And it’s very good for hard rock,” the type present at the facility.

Along with excavation of the main caverns, crews will also enlarge some of the drifts and the area around the Ross Shaft to create more space for transporting the DUNE equipment. For this excavation as well as the eventual excavation of the main caverns, the teams will switch to the “drill and blast” technique, using explosive charges placed in small holes.

Working underground isn’t always easy, but the crews are highly trained and work with state-of-the-art equipment.

“It can be dark; it can be dirty; it can get hot,” Rickard said. “But it’s a way of life that these workers are used to. And we have everything modern — we’ve got modern equipment and good ventilation.”

Driven by science

When the space is ready, researchers will begin bringing all of the components needed for the massive experiment underground and assembling the detector, like a ship in a bottle.

DUNE will address three major science goals: determine why matter exists in the universe; watch for neutrinos from a supernova in our galaxy; and look for unexpected subatomic processes, such as proton decay, a phenomenon that has never been observed before.

Fermilab’s Elaine McCluskey, the project manager for LBNF/DUNE-US, said while the excavation process may take years, keeping the future science goals in mind helps her stay excited.

“It feels like we’re actually accomplishing the goal that we all want to get to, which is to enable the scientists to take data,” McCluskey said. “Neutrinos will help us understand more about our universe and ourselves. People want to know why we’re here, why we exist. DUNE will bring us closer to the answers to these questions.”

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.