Editor’s note: Below is a press release issued by the Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory.

The MicroBooNE detector is lowered into the main cavern of the Liquid Argon Test Facility at Fermilab. Photo: Fermilab

UPTON, N.Y. — How do you spot a subatomic neutrino in a “haystack” of particles streaming from space? That’s the daunting prospect facing physicists studying neutrinos with detectors near Earth’s surface. With little to no shielding in such non-subterranean locations, surface-based neutrino detectors, usually searching for neutrinos produced by particle accelerators, are bombarded by cosmic rays — relentless showers of subatomic and nuclear particles produced in Earth’s atmosphere by interactions with particles streaming from more-distant cosmic locations. These abundant travelers, mostly muons, create a web of crisscrossing particle tracks that can easily obscure a rare neutrino event.

Fortunately, physicists have developed tools to tone down the cosmic “noise.”

A team including physicists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory describes the approach in two papers recently accepted to be published in Physical Review Applied and the Journal of Instrumentation. These papers demonstrate the scientists’ ability to extract clear neutrino signals from the MicroBooNE detector at DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The method combines CT-scanner-like image reconstruction with data-sifting techniques that make accelerator-produced neutrino signals stand out 5 to 1 against the cosmic ray background.

“We developed a set of algorithms that reduce the cosmic ray background by a factor of 100,000,” said Chao Zhang, one of the Brookhaven Lab physicists who helped to develop the data-filtering techniques. Without the filtering, MicroBooNE would see 20,000 cosmic rays for every neutrino interaction, he said. “This paper demonstrates the crucial ability to eliminate the cosmic ray backgrounds.”

Bonnie Fleming, a professor at Yale University who is a co-spokesperson for MicroBooNE, said, “This work is critical both for MicroBooNE and for the future U.S. neutrino research program. Its impact will extend notably beyond the use of this ‘Wire-Cell’ analysis technique, even on MicroBooNE, where other reconstruction paradigms have adopted these data-sorting methods to dramatically reduce cosmic ray backgrounds.”

Tracking neutrinos

MicroBooNE is one of three detectors that form the international Short-Baseline Neutrino program at Fermilab, each located a different distance from a particle accelerator that generates a carefully controlled neutrino beam. The three detectors are designed to count up different types of neutrinos at increasing distances to look for discrepancies from what’s expected based on the mix of neutrinos in the beam and what’s known about neutrino “oscillation.” Oscillation is a process by which neutrinos swap identities among three known types, or “flavors.” Spotting discrepancies in neutrino counts could point to a new unknown oscillation mechanism — and possibly a fourth neutrino variety.

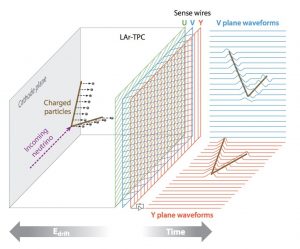

How the MicroBooNE detector works: The neutrino interaction creates charged particles and generates a flash of light. The charged particles ionize the argon atoms and create free electrons. The electrons drift toward the three wire planes under an external electric field and induce signals on the wires. The wires effectively record three images of the particle activities from different angles. The light flashes (photons) are detected by photomultiplier tubes behind the wire planes, which tells when the interaction happens. Scientists use the images from the three planes of wires and the timing of the interaction to reconstruct the tracks created by the neutrino interaction and where it occurred in the detector. Illustration: MicroBooNE collaboration

Brookhaven Lab scientists played a major role in designing the MicroBooNE detector, particularly the sensitive electronics that operate within the detector’s super-cold liquid-argon-filled time projection chamber. As neutrinos from Fermilab’s accelerator enter the chamber, every so often a neutrino will interact with an argon atom, kicking some particles out of its nucleus — a proton or a neutron — and generating other particles (muons, pions) and a flash of light. The charged particles that get kicked out ionize argon atoms in the detector, knocking some of their electrons out of orbit. The electrons that form along these ionization tracks get picked up by the detector’s sensitive electronics.

“The whole trail of electrons drifts along an electric field and passes through three consecutive planes of wires with different orientations at one end of the detector,” Zhang said. “As the electrons approach the wires, they induce a signal, so that each set of wires creates a 2D image of the track from a different angle.”

Meanwhile, the flashes of light created at the time of the neutrino interaction get picked up by photomultiplier tubes that lie beyond the wire arrays. Those light signals tell scientists when the neutrino interaction took place and how long it took the tracks to arrive at the wire planes.

Computers translate that timing into distance and piece together the 2D track images to reconstruct a 3D image of the neutrino interaction in the detector. The shape of the track tells scientists which flavor of neutrino triggered the interaction.

“This 3D ‘Wire-Cell’ image reconstruction is similar to medical imaging with a computed tomography scanner,” Zhang explained. In a CT scanner, sensors capture snapshots of the body’s internal structures from different angles and computers piece the images together. “Imagine the particle tracks going through the three wire planes as a person going into the scanner,” he said.

Untangling the cosmic web

It sounds almost simple — if you forget about the thousands of cosmic rays that stream through the detector at the same time. Their ionization trails also drift through the scanning wires, creating images that look like a tangled web. That’s why MicroBooNE scientists have been working on sophisticated “triggers” and algorithms to sift through the data so they can extract the neutrino signals.

By 2017, they had made substantial progress reducing the cosmic ray noise. But even then, cosmic rays outnumbered neutrino tracks by about 200 to 1. The new papers describe further techniques to reduce this ratio, and flip it to the point where neutrino signals in MicroBooNE now stand out 5 to 1 against the cosmic ray background.

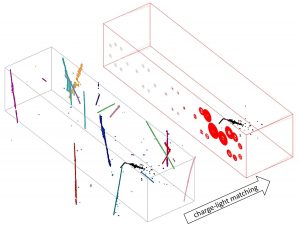

The first step involves matching the signals revealed by particles generated in neutrino interactions with the exact flashes of light picked up by the photomultiplier tubes from that interaction.

The MicroBooNE time projection chamber is loaded into the container vessel. The photomultiplier tubes mounted at the back of the chamber help to identify particle tracks generated by neutrinos in the time projection chamber by detecting simultaneously generated flashes of light. Photo: Fermilab

“This is not easy!” said Brookhaven Lab physicist Xin Qian. “Because the time projection chamber and the photomultiplier tubes are two different systems, we don’t know which flash corresponds to which event in the detector. We have to compare the light patterns for each photomultiplier tube with all the locations of these particles. If you’ve done all the matching correctly, you will find a single 3D object that corresponds to a single flash of light measured by the photomultiplier tubes.”

Brooke Russell, who worked on the analysis as a Yale graduate student and is now a postdoctoral fellow at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, echoed these comments on the challenge of light-matching. “Given that the charge information is in some cases not fully complementary to the light information, there can be ambiguities in charge-light pairings on a single-readout basis. The algorithms developed by the team help to account for these nuances,” she said.

Still, the scientists must then compare the timing of each track with the time accelerator neutrinos were emitted (a factor they know because they control the accelerator beam). “If the timing is consistent, then it is a possible neutrino interaction,” Qian said.

The algorithm developed by the Brookhaven team brings the ratio down to one neutrino for every six cosmic ray events.

Rejecting additional cosmic rays gets a bit easier with an algorithm that eliminates tracks that completely traverse the detector.

“Most cosmic rays go through the detector from top to bottom or from one side to the other,” said Xiangpan Ji, a Brookhaven Lab postdoc working on this algorithm. “If you can identify the point of entry and exit of the track, you know it’s a cosmic ray. Particles formed by neutrino interactions have to start in the middle of the detector where that interaction takes place.”

That brings the ratio of neutrino interactions to cosmic rays to 1:1.

An example electron-neutrino event before and after applying the “charge-light” matching algorithm. A neutrino interaction is typically mixed with about 20 cosmic rays during the event recording of 4.8 milliseconds. After matching the neutrino interaction’s “charge” signal, recorded by the wires, with its “light” signal, recorded by the photomultiplier tubes, it can be clearly singled out from the cosmic ray background. In the event display, the black points are from the electron-neutrino interaction and the colored points are the background cosmic rays. The size of each red circle shows the strength of the matched light signal for each photomultiplier tube. Illustration: MicroBooNE collaboration

An additional algorithm screens out events that start outside the detector and get stopped somewhere in the middle — which look similar to neutrino events but move in the opposite direction. And one final fine-tuning step rules out events where the light flashes don’t match well with events, to bring the detection of neutrino events to the remarkable level of 5 to 1 compared with cosmic rays.

“This is one of the most challenging analyses I have worked on,” said Hanyu Wei, the Brookhaven Lab postdoctoral fellow leading the analysis effort. “The liquid-argon time projection chamber is a new detector technology with lots of surprising features. We had to invent many original methods. It was truly a team effort.”

Zhang echoed that sentiment and said, “We expect this work to significantly boost the potential for the MicroBooNE experiment to explore the intriguing physics at short baselines. Indeed, we’re looking forward to implementing these techniques in experiments at all three short-baseline neutrino detectors to see what we learn about neutrino oscillations and the possible existence of a fourth neutrino type.”

This work was funded by the DOE Office of Science. The Fermilab Accelerator Complex that creates the neutrinos for MicroBooNE and the other short-baseline neutrino experiments is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://www.energy.gov/science/.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC, a joint partnership between the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association, Inc. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

Professor Alfons Weber will supervise the design and construction of the so-called DUNE Near Detector complex, which will be located close to the source of the neutrino beams at Fermilab.

Editor’s note: Below is a press release issued by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

Neutrino physics is one of the main focuses of the PRISMA+ Cluster of Excellence at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), with many of its researchers participating in several large international experiments at the South Pole, in Italy and in China. Now, JGU together with Fermilab has appointed Alfons Weber as a new W3 professor. Weber, a leading specialist when it comes to neutrinos, will move to Mainz from the eminent University of Oxford, further reinforcing the neutrino research program here. His primary objective is to promote German participation in the next major neutrino experiment, Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), at Fermilab located near Chicago.

“We are very pleased that we were able to make this joint appointment in collaboration with Fermilab,” explains JGU President, Prof. Georg Krausch. “The fact of our cooperation demonstrates the exceptional reputation of our PRISMA+ Cluster of Excellence and the outstanding quality of research undertaken here, and confirms once again the international standing of our Mainz-based physicists.”

“On behalf of Fermilab, congratulations to Prof. Alfons Weber on obtaining his full professorship at the University of Mainz,” says Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer. “He is well known for his leadership role in the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment and will bring a wealth of knowledge and experience to Mainz. We look forward to his continued leadership in the DUNE research program.”

Weber will be relocating to Mainz on June 28, 2021. “I am very much looking forward to my new responsibilities both in Mainz and at Fermilab. Being involved in developing the DUNE experiment is a complex and exciting challenge. I am convinced this cooperation with the team in Mainz who are conducting research into neutrinos and high-energy accelerators will generate synergies and lead to new insights.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory – Fermilab for short – is the national research laboratory for particle and high-energy physics in the USA. More than 1,000 scientists from over 30 countries are collaborating on DUNE, hosted by Fermilab. They plan to send neutrino and antineutrino beams 1,300 kilometers straight through the earth. As they make this journey, the three well-known types of neutrino will be constantly changing into one other. “By better understanding this process – something we call neutrino oscillation – we hope to find out whether neutrinos are responsible for the fact there is far more matter than antimatter in the universe,” Alfons Weber explains. The beams originate at the Fermilab particle accelerator complex near Chicago and will travel through dirt and rock—no tunnel needed—to the enormous particle detectors located at the Sanford Underground Research Laboratory in South Dakota. Prep work is underway for the excavation of about 800,000 tons of rock to create the huge caverns for the DUNE far detectors.

His primary task is to supervise the design and construction of the so-called DUNE Near Detector complex, which will be located close to the source of the neutrino beams at Fermilab. “This is mainly necessary to analyze the neutrino beams before we send them on their long trip,” says Alfons Weber. “This is because, to put it figuratively, we can only make statements about what arrives at the finish line if we know exactly what’s leaving the starting blocks. So we need this initial analysis in order to be able to interpret the results later on.”

Various universities in Germany have teamed up to design and build a prototype for a specific measuring device to be incorporated in the DUNE detectors; this will be an electromagnetic calorimeter that can detect particles such as photons, neutrons and electrons. The PRISMA detector laboratory is playing a crucial role in this project, due to the tremendous amount of expertise and highly specialized know-how it offers, in terms of both the development of fast electronic devices as well as the construction of prototypes.

Weber is confident that, “The accelerator-based neutrino physics that we will be studying with the help of DUNE will deliver significant results in the next few years and will comprehensively extend our understanding of these omnipresent yet elusive ghost particles.” He will undertake the majority of his research at PRISMA+ in Mainz, but will also regularly visit Fermilab for extended research stays.

Profile:

Alfons Weber studied physics at RWTH Aachen University and had already begun focusing on neutrinos in his diploma thesis written in 1989. While studying for his doctorate and working at CERN’s large Electron Positron Collider, he initially concentrated on researching the W boson before once again turning to neutrinos after being appointed to a post at the University of Oxford in 1999. First as a departmental lecturer and later as a professor, he was involved in the earlier MINOS project at Fermilab and the T2K experiment in Japan, which is dedicated to neutrino oscillation research. In Oxford, he also coordinated and led the British participation in the planned DUNE experiment. Alfons Weber was born in 1965 and is married with two children. In his free time, he enjoys sailing and reading fantasy and sci-fi novels.

More information: Press release Mainz University, Fermilab agree to joint appointment in support of Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (Sept. 5, 2019)

The international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment is supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.