The more than 1,000 scientists and engineers from 32 countries working on the international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), hosted by the Department of Energy’s Fermilab, achieved a milestone on July 29 when the collaboration released its 687-page Interim Design Report for the construction of gigantic particle detector modules a mile underground in South Dakota.

The three-volume interim report, which was posted on the scientific online repository arXiv (Volume One, Volume Two, Volume Three), summarizes the DUNE physics goals and the design of the detector to meet these goals. It is based on the experience that DUNE scientists have gained during the design and construction of three-story-tall prototype detectors at CERN in Europe. The final detector modules, to be sited in the United States, will be about 20 times the size of the prototypes.

“It is amazing how much work this collaboration has accomplished in the last couple of years,” said DUNE co-spokesperson Stefan Soldner-Rembold, professor at the University of Manchester in the UK. “The Interim Design Report is a major step toward the preparation of the final, more detailed Technical Design Report, which we will write next.”

The DUNE Technical Design Report for the first two detector modules will be finalized roughly a year from now and will be the blueprint for the construction of those modules.

“The Interim Design Report presents an enormous body of work,” said Sam Zeller, Fermilab, who served as the co-editor of the document together with Tim Bolton, Kansas State University. “The document doesn’t just contain drawings. It also includes detailed technical specifications and photos of the prototype equipment that was built during the last 12 months.”

DUNE is an experiment to unlock the mysteries of neutrinos, the particles that could be the key to explaining why matter and the universe exist. The experiment will send a neutrino beam generated by Fermilab’s particle accelerator complex in Illinois 800 miles straight through Earth to the DUNE far detector modules to be built at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. DUNE scientists also will use the large detector modules to search for rare subatomic processes such as proton decay and watch for neutrinos stemming from the explosion of stars in our galaxy.

The giant DUNE detector will record images of particle tracks created by neutrinos colliding with argon atoms.

“The DUNE physics program addresses key questions that will give us further insight in the understanding of the universe,” said DUNE collaborator Albert de Roeck, leader of the CERN experimental neutrino group. “Neutrinos are still very enigmatic particles and no doubt will surprise us in future.”

Groundbreaking for the construction of the caverns that will host the DUNE modules took place in July 2017, and the experiment is expected to be operational with two far detector modules online by 2026. Ultimately, DUNE will comprise four far detector modules filled with a total of 70,000 tons of liquid argon, as well as a smaller near detector at Fermilab.

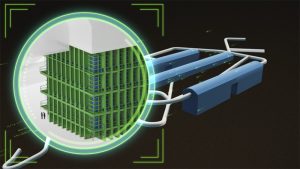

The Interim Design Report specifies the two technologies that DUNE scientists will use for the far detector: single- and dual-phase time projection chambers filled with cold, crystal clear liquid argon, the same technologies used to build the two prototype detectors at CERN, known as the ProtoDUNE detectors.

“Designing liquid-argon time projection chambers of this size is an unprecedented effort requiring state-of-the-art technologies,” said CNRS Research Director Dario Autiero of the French National Institute of Nuclear and Particle Physics, Institut de Physique Nucleaire, Lyon, and DUNE collaborator. “DUNE pushes the technological limits in detector design, high-voltage systems, photon detection systems, low-noise electronics, and high-bandwidth data acquisition systems. DUNE collaborators have been developing these technologies for years, and they are being deployed in the two prototype detectors at CERN.”

Both types of far detector modules will record images of particle tracks created by neutrinos colliding with argon atoms. In the single-phase technology, the entire volume of the detector is filled with liquid argon, and a horizontal high-voltage electric field “projects” the particle tracks towards the walls of the detector. Arrays of thin wires placed in front of the detector walls capture the signals created by the particle tracks and send them to a data acquisition system.

“These giant detectors are being designed and developed by a great team of scientists and engineers, working together to unveil the secrets of the universe,” said Inés Gil-Botella, leader of the CIEMAT neutrino group, Madrid, Spain, and member of the DUNE collaboration. “Careful planning and coordination is the key to the success of DUNE.”

The three volumes of the DUNE Far Detector Interim Design Report are available online: Volume One, Volume Two, Volume Three.

The DUNE collaboration comprises 175 institutions from 32 countries: Armenia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Greece, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, Madagascar, Mexico, Netherlands, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and United States. More information is at dunescience.org.

To learn more about the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility that will house the experiment, and the PIP-II particle accelerator project at Fermilab that will power the neutrino beam for the experiment, visit www.fnal.gov/dune.

Fermilab’s accelerator complex has achieved a major milestone: The U.S. Department of Energy formally approved Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory to proceed with its design of PIP-II, an accelerator upgrade project that will provide increased beam power to generate an unprecedented stream of neutrinos — subatomic particles that could unlock our understanding of the universe — and enable a broad program of physics research for many years to come.

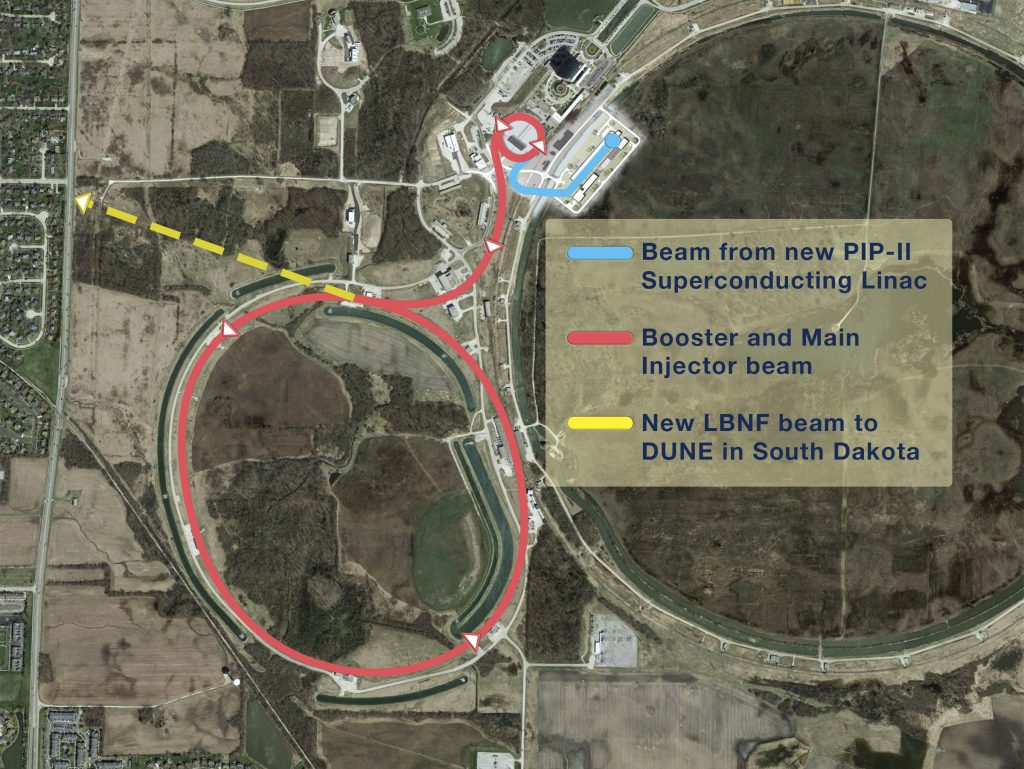

The PIP-II (Proton Improvement Plan II) accelerator upgrades are integral to the Fermilab-hosted Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), which is the largest international science experiment ever to be conducted on U.S. soil. DUNE requires enormous quantities of neutrinos to study the mysterious particle in exquisite detail and, with the latest approval for PIP-II, Fermilab is positioned to be the world leader in accelerator-based neutrino research. The Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility (LBNF), which will also support DUNE, had its groundbreaking ceremony in July 2017.

The opportunity to contribute to PIP-II has drawn scientists and engineers from around the world to Fermilab: PIP-II is the first accelerator project on U.S. soil that will have significant contributions from international partners. Fermilab’s PIP-II partnerships include institutions in India, Italy, the UK, and potentially France, as well as the United States.

PIP-II capitalizes on recent particle accelerator advances developed at Fermilab and other institutions that will allow its accelerators to generate particle beams at higher powers than previously available. The high-power particle beams will in turn create intense neutrino beams, providing scientists with an abundance of these subtle particles.

“PIP-II’s high-power accelerators and its national and multinational partnerships reinforce Fermilab’s position as the accelerator-based neutrino physics capital of the world,” said DOE Undersecretary for Science Paul Dabbar. “LBNF/DUNE, the Fermilab-based megascience experiment for neutrino research, has already attracted more than 1,000 collaborators from 32 countries. With the accelerator side of the experiment ramping up in the form of PIP-II, not only does Fermilab attract collaborators worldwide to do neutrino science, but U.S. particle physics also gets a powerful boost.”

The Department of Energy’s Argonne and Lawrence Berkeley national laboratories are also major PIP-II participants.

This architectural rendering shows the buildings that will house the new PIP-II accelerators. Architectural rendering: Gensler. Image: Diana Brandonisio

A major milestone

The DOE milestone is formally called Critical Decision 1 approval, or CD-1. In granting CD-1, DOE approves Fermilab’s approach and cost range. The milestone marks the completion of the project definition phase and the conceptual design. The next step is to move the project toward establishing a performance baseline.

“We think of PIP-II as the heart of Fermilab: a platform that provides multiple capabilities and enables broad scientific programs, including the most powerful accelerator-based neutrino source in the world,” said Fermilab PIP-II Project Director Lia Merminga. “With the go-ahead to refine our blueprint, we can focus designing the PIP-II accelerator complex to be as powerful and flexible as it can possibly be.”

PIP-II’s powerful neutrino stream

Neutrinos are ubiquitous yet fleeting particles, the most difficult to capture of all of the members of the subatomic particle family. Scientists capture them by sending neutrino beams generated from particle accelerators to large, stories-high detectors. The greater the number of neutrinos sent to the detectors, the greater the chances the detectors will catch them, and the more opportunity there is to study these subatomic escape artists.

That’s where PIP-II comes in.

Fermilab’s upgraded PIP-II accelerator complex will generate proton beams of significantly greater power than is currently available. The increase in beam power translates into more neutrinos that can be sent to the lab’s various neutrino experiments. The result will be the world’s most intense high-energy neutrino beam.

The goal of PIP-II is to produce a proton beam of more than 1 megawatt, about 60 percent higher than the existing accelerator complex supplies. Eventually, enabled by PIP-II, Fermilab could upgrade the accelerator to double that power to more than 2 megawatts.

“At that power, we can just flood the detectors with neutrinos,” said DUNE co-spokesperson and University of Chicago physicist Ed Blucher. “That’s what so exciting. Every neutrino that stops in our detectors adds a bit of information to our picture of the universe. And the more neutrinos that stop, the closer we get to filling in the picture.”

The largest and most ambitious of these detectors are those in DUNE, which is scheduled to start up in the mid-2020s. DUNE will use two detectors separated by a distance of 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) — one at Fermilab and a second, much larger detector situated one mile underground in South Dakota at the Sanford Underground Research Facility. Prototypes of those technologically advanced neutrino detectors are now under construction at the European particle physics laboratory CERN, which is a major partner in LBNF/DUNE, and are expected to take data later this year.

Fermilab’s accelerators, enhanced according to the PIP-II plan, will send a beam of neutrinos to the DUNE detector at Fermilab. The beam will continue its path straight through Earth’s crust to the detector in South Dakota. Scientists will study the data gathered by both detectors, comparing them to get a better handle on how neutrino properties change over the long distance.

The detector located in South Dakota, known as the DUNE far detector, is enormous. It will stand four stories high and occupy an area equivalent to a soccer field. With its supporting platform LBNF, DUNE is designed to handle a neutrino deluge.

And, with the cooperation of international partners, PIP-II is designed to deliver it.

The PIP-II project will supply powerful neutrino beams for the LBNF/DUNE experiment. Image: Diana Brandonisio

Partners in PIP-II

The development of a major particle accelerator with international participation represents a new paradigm in U.S. accelerator projects: PIP-II is the first U.S.-based accelerator project with multinational partners. Currently these include laboratories in India (BARC, IUAC, RRCAT, VECC) and institutions in Italy, funded by the National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN), in the UK, funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), and potentially in France (CEA and CNRS).

In an agreement with India, four Indian Department of Atomic Energy institutions are authorized to contribute equipment, with details to be formalized in advance of the start of construction.

“The international scientific community brings world-leading expertise and capabilities to the project. Their engagement and shared sense of ownership in the project’s success are among the most compelling strengths of PIP-II,” Merminga said.

PIP-II partners contribute accelerator components, pursuing their development jointly with Fermilab through regular exchanges of scientists and engineers. The collaboration is mutually beneficial. For some international partners, this collaboration presents an opportunity for development of their own facilities and infrastructure as well as local accelerator industry.

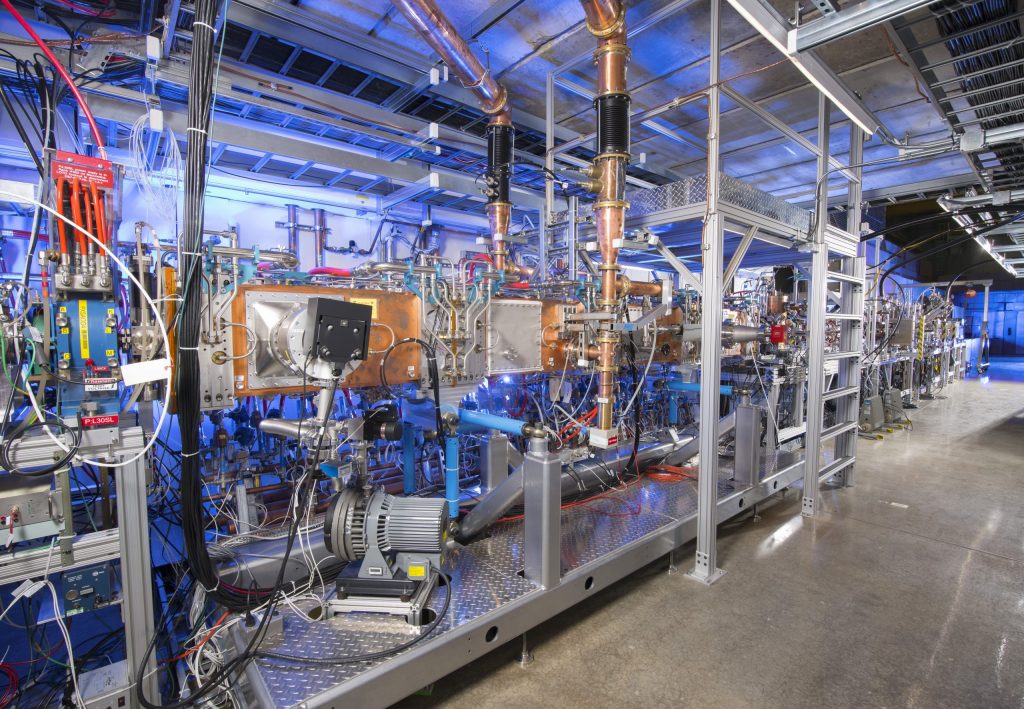

Fermilab is currently developing the front end of the PIP-II linear accelerator for tests of the relevant technology. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Accelerating superconducting technology

The centerpiece of the PIP-II project is the construction of a new superconducting radio-frequency (SRF) linear accelerator, which will become the initial stage of the upgraded Fermilab accelerator chain. It will replace the current Fermilab Linac. (“Linac” is a common abbreviation for “linear accelerator,” in which the particle beam proceeds along a straight path.) The plan is to install the SRF linac under 25 feet of dirt in the infield of the now decommissioned Tevatron ring.

The new SRF linac will provide a big boost to its particle beam from the get-go, doubling the beam energy of its predecessor from 400 million to 800 million electronvolts. That boost will enable the Fermilab accelerator complex to achieve megawatt-scale beam power.

Superconducting materials carry zero electrical resistance, so current sails through them effortlessly. By taking advantage of superconducting components, accelerators minimize the amount of power they draw from the power grid, channeling more of it to the beam. Beams thus achieve higher energies at less cost than in normal-conducting accelerators, such as Fermilab’s current Linac.

In the linac, superconducting components called accelerating cavities will impart energy to the particle beam. The cavities, which look like strands of jumbo, silver pearls, are made of niobium and will be lined up end to end. The particle beam will accelerate down the axis of one cavity after another, picking up energy as it goes.

“Fermilab is one of the pioneers in superconducting accelerator technology,” Merminga said. “Many of the advances developed here are going into the PIP-II SRF linac.”

The linac cavities will be encased in 25 cryomodules, which house cryogenics to keep the cavities cold (to maintain superconductivity).

Many current and future particle accelerators are based on superconducting technology, and the advances that help scientists study neutrinos have multiplying effects outside fundamental science. Researchers are developing superconducting accelerators for medicine, environmental cleanup, quantum computing, industry and national security.

In PIP-II, a beam of protons will be injected into the linac. Over the course of its 176 meters — three-and-a-half Olympic-size pool lengths — the beam will accelerate to an energy of 800 million electronvolts. Once it passes through the superconducting linac, it will enter the rest of Fermilab’s current accelerator chain — a further three accelerators — which will also undergo significant upgrades over the next few years to handle the higher-energy beam from the new linac. By the time the beam exits the final accelerator, it will have an energy of up to 120 billion electronvolts and more than 1 megawatt of power.

After the proton beam exits the chain, it will strike a segmented cylinder of carbon. The beam-carbon collision will create a shower of other particles, which will be routed to various Fermilab experiments. Some of these post-collision particles will become — will “decay into,” in physics lingo — neutrinos, which will by this point already be on the path toward their detectors.

PIP-II’s initial proton beam — which scientists will be able to distribute between LBNF/DUNE and other experiments — can be delivered in pulses or as a continuous proton stream.

The front-end components for PIP-II — those upstream from the superconducting linac — are already developed and undergoing testing.

“We are very happy to have been able to design PIP-II to meet the requirements of the neutrino program while providing flexibility for future development of the Fermilab experimental program in any number of directions,” said Fermilab’s Steve Holmes, former PIP-II project director.

Fermilab expects to complete the project by the mid-2020s, in time for the startup of LBNF/DUNE.

“Many people worked tirelessly to design the best machine for the science we want to do,” Merminga said. “The recognition of their excellent work through CD-1 approval is encouraging for us. We look forward to building this forefront accelerator.”

Department of Energy funding for the project is provided through DOE’s Office of Science.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC, a joint partnership between the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association Inc. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.