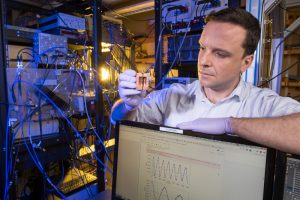

Daniel Bowring examines a superconducting qubit mounted in a copper microwave cavity. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Dark matter makes up nearly 80 percent of all matter in the universe, yet its nature has eluded scientists. Scientists theorize that it could take the form of a subatomic particle, and one possible candidate comes in the form of a small, theoretical particle called the axion. If it exists, the axion will interact incredibly weakly with matter, so detecting one requires an incredibly sensitive detector.

Fermilab scientist Daniel Bowring is planning to build just such an instrument. The Department of Energy has selected Bowring for a 2018 Early Career Research Award to build a detector that would ferret out the hypothesized particle. He will receive $2.5 million over five years to build and operate his experiment. The award funds equipment, engineers, technicians and a postdoctoral researcher.

“We are very motivated to find the axion because it would solve several interesting problems for us in the particle physics community,” Bowring said.

Not only would the axion’s discovery explain, at least in part, the nature of dark matter, it could also solve the strong CP problem, a long-standing thorn in the side of theoretical physics models.

The strong CP problem is an inconsistency in particle physics. Particles behave differently from their mirror-reversed, antimatter counterparts — at least, they do under the influence of the electromagnetic force and the weak nuclear force (which governs nuclear decay).

But under the influence of the strong force (which holds matter together), particles and their mirror-image antiparticles behave similarly. Or, in physics speak, they’re CP-symmetric under the strong force. (CP stands for charge-parity. It’s the property that’s flipped when you take a mirror image of a particle’s antimatter partner.) Why is the strong force the exception?

One potential answer lies in the existence of the axion. In the math of strong interactions, the addition of the axion enables theoretical models to reflect the reality of strong-force CP symmetry.

Bowring is following the axion math where it leads — to the construction of a device that can pick up the signal of the fundamental particle, whose mass is predicted to be vanishingly small, between 1 billion and 1 trillion times smaller than an electron.

One way to look for the axion is to look for light: In the presence of a strong electromagnetic field — Bowring’s experiment will use about 14 Tesla, or roughly 10 times stronger than an MRI magnet — an axion should convert into a single particle of light, called a photon, which is more easily observed.

“Physicists have gotten pretty good at detecting photons over the years,” Bowring said.

When an axion enters the detector filled with the electromagnetic field, the particle will spontaneously convert into a photon with a specific frequency. The frequency corresponds to the axion’s mass, so scientists can measure the axion mass indirectly, thanks to the detection of particles of light.

Much like someone tuning a sensitive AM radio, researchers will scan slowly through the relevant range of photon frequencies until they pick up a signal, which would point to the presence of an axion.

It’s a subtle business, one that requires being able to detect single photons. While photon detection is an old hat for physicists, discerning a lone photon amid the experimental noise of a particle detector is a job for new technology. Bowring’s experiment will use supersensitive, superconducting quantum bits, or qubits, to pluck the solo photon signal from the noise and thus accurately count the number of detected photons.

Bowring’s experiment will be an opportunity to bridge the gap between particle physics and the science behind quantum computing.

“Daniel’s proposed experiment will demonstrate how qubits, the essential elements of quantum computing, can be used to detect a range of axion masses,” said Fermilab scientist Keith Gollwitzer. “Quantum computing may be the next large step in computing power and particle physics experiments.”

In that respect, the application of technologies in their infancy to century-old problems is a reflection of the larger scientific field.

“Fermilab’s mission is doing particle physics, and qubits are just a way for us to meet the requirements of that mission,” Bowring says. “It is a way for us to build new experiments that address the problems of particle physics at the forefront of where the field is.”

Editor’s note: The following press release was issued by Brookhaven National Laboratory, one of 34 collaborating institutions in seven countries working on the new Muon g-2 experiment at Fermilab. The Muon g-2 experiment completed construction on schedule and under budget in January 2018. The collaboration is now taking physics data with Fermilab’s powerful beamline and will use it to study muons with unprecedented accuracy. By comparing real-world results to precise predictions, physicists can determine whether new physics is afoot. The results reported here are part of a global Muon g-2 Theory Initiative launched at Fermilab last June.

Latest calculation based on how subatomic muons interact with all known particles comes out just in time for precision measurements at new “Muon g-2” experiment

Theoretical physicists at Brookhaven National Laboratory recently published in Physical Review Letters a calculation related to the way muons interact with all other known particles through three of nature’s four fundamental forces, reducing the greatest source of uncertainty in the prediction. The result comes out just in time for precision measurements at Fermilab’s Muon g-2 experiment, pictured here. Photo: Reidar Hahn

UPTON, NY—Theoretical physicists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and their collaborators have just released the most precise prediction of how subatomic particles called muons—heavy cousins of electrons—“wobble” off their path in a powerful magnetic field. The calculations take into account how muons interact with all other known particles through three of nature’s four fundamental forces (the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear force and electromagnetism) while reducing the greatest source of uncertainty in the prediction. The results, published in Physical Review Letters, come just in time for the start of a new experiment measuring the wobble now under way at DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

A version of this experiment, known as Muon g-2, ran at Brookhaven Lab in the late 1990s and early 2000s, producing a series of results indicating a discrepancy between the measurement and the prediction. Although not quite significant enough to declare a discovery, those results hinted that new, yet-to-be discovered particles might be affecting the muons’ behavior. The new experiment at Fermilab, combined with the higher-precision calculations, will provide a more stringent test of the Standard Model, the reigning theory of particle physics. If the discrepancy between experiment and theory still stands, it could point to the existence of new particles.

“If there’s another particle that pops into existence and interacts with the muon before it interacts with the magnetic field, that could explain the difference between the experimental measurement and our theoretical prediction,” said Christoph Lehner, one of the Brookhaven Lab theorists involved in the latest calculations. “That could be a particle we’ve never seen before, one not included in the Standard Model.”

Finding new particles beyond those already cataloged by the Standard Model has long been a quest for particle physicists. Spotting signs of a new particle affecting the behavior of muons could guide the design of experiments to search for direct evidence of such particles, said Taku Izubuchi, another leader of Brookhaven’s theoretical physics team.

“It would be a strong hint and would give us some information about what this unknown particle might be — something about what the new physics is, how this particle affects the muon and what to look for,” Izubuchi said.

The muon anomaly

The Muon g-2 experiment measures what happens as muons circulate through a 50-foot-diameter electromagnet storage ring. The muons, which have intrinsic magnetism and spin (sort of like spinning toy tops), start off with their spins aligned with their direction of motion. But as the particles go ’round and ’round the magnet racetrack, they interact with the storage ring’s magnetic field and also with a zoo of virtual particles that pop in and out of existence within the vacuum. This all happens in accordance with the rules of the Standard Model, which describes all the known particles and their interactions, so the mathematical calculations based on that theory can precisely predict how the muons’ alignment should precess, or “wobble,” away from their spin-aligned path. Sensors surrounding the magnet measure the precession with extreme precision so the physicists can test whether the theory-generated prediction is correct.

Both the experiments measuring this quantity and the theoretical predictions have become more and more precise, tracing a journey across the country with input from many famous physicists.

A race and collaboration for precision

“There is a race of sorts between experiment and theory,” Lehner said. “Getting a more precise experimental measurement allows you to test more and more details of the theory. And then you also need to control the theory calculation at higher and higher levels to match the precision of the experiment.”

With lingering hints of a new discovery from the Brookhaven experiment — but also the possibility that the discrepancy would disappear with higher-precision measurements — physicists pushed for the opportunity to continue the search using a higher-intensity muon beam at Fermilab. In the summer of 2013, the two labs teamed up to transport Brookhaven’s storage ring via an epic land-and-sea journey from Long Island to Illinois. After tuning up the magnet and making a slew of other adjustments, the team at Fermilab recently started taking new data.

Meanwhile, the theorists have been refining their calculations to match the precision of the new experiment.

“There have been many heroic physicists who have spent a huge part of their lives on this problem,” Izubuchi said. “What we are measuring is a tiny deviation from the expected behavior of these particles — like measuring a half a millimeter deviation in the flight distance between New York and Los Angeles! But everything about the fate of the laws of physics depends on that difference. So, it sounds small, but it’s really important. You have to understand everything to explain this deviation,” he said.

The path to reduced uncertainty

By “everything,” he means how all the known particles of the Standard Model affect muons via nature’s four fundamental forces — gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force and the electroweak force. Fortunately, the electroweak contributions are well understood, and gravity is thought to play a currently negligible role in the muon’s wobble. So the latest effort — led by the Brookhaven team with contributions from the RBC Collaboration (made up of physicists from the RIKEN BNL Research Center, Brookhaven Lab and Columbia University) and the UKQCD collaboration — focuses specifically on the combined effects of the strong force (described by a theory called quantum chromodynamics, or QCD) and electromagnetism.

“This has been the least understood part of the theory, and therefore the greatest source of uncertainty in the overall prediction. Our paper is the most successful attempt to reduce those uncertainties, the last piece at the so-called “precision frontier” — the one that improves the overall theory calculation,” Lehner said.

The mathematical calculations are extremely complex — from laying out all the possible particle interactions and understanding their individual contributions to calculating their combined effects. To tackle the challenge, the physicists used a method known as lattice QCD, originally developed at Brookhaven Lab, and powerful supercomputers. The largest was the Leadership Computing Facility at Argonne National Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science user facility, while smaller supercomputers hosted by Brookhaven’s Computational Sciences Initiative (CSI) — including one machine purchased with funds from RIKEN, CSI and Lehner’s DOE Early Career Research Award funding — were also essential to the final result.

“One of the reasons for our increased precision was our new methodology, which combined the most precise data from supercomputer simulations with related experimental measurements,” Lehner noted.

Other groups have also been working on this problem, he said, and the entire community of about 100 theoretical physicists will be discussing all of the results in a series of workshops over the next several months to come to agreement on the value they will use to compare with the Fermilab measurements.

“We’re really looking forward to Fermilab’s results,” Izubuchi said, echoing the anticipation of all the physicists who have come before him in this quest to understand the secrets of the universe.

The theoretical work at Brookhaven was funded by the DOE Office of Science, RIKEN and Lehner’s Early Career Research Award.

The Muon g-2 experiment at Fermilab is supported by DOE’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation. The Muon g-2 collaboration has almost 200 scientists and engineers from 34 institutions in seven countries. Learn more about the new Muon g-2 experiment or take a virtual tour.

Brookhaven National Laboratory and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory are both supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on or find them on Facebook.