The Fermilab Booster has been bringing some serious beam.

As one of the accelerators in the accelerator chain at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, the Booster feeds particle beams to all the lab’s accelerator-based physics experiments. As a general rule, the more beam an accelerator can provide, the better.

Following significant upgrades to the accelerator complex, over the last year the Booster has been hitting record highs in beam delivery, meeting or exceeding the increased needs of all of the lab’s beam-based experiments. This year it has already delivered 1 billion trillion protons, smashing previous yearly proton delivery records.

Impressively, the lab’s accelerator team has also doubled the beam intensity — the number of particles packed into the beam.

“It’s outstanding,” said Fermilab engineer Bill Pellico, manager of the Fermilab Proton Improvement Plan, or PIP, a program for upgrading the lab accelerator complex. “Before the upgrades, we could feed only one of our three beamlines at a time at its full, requested intensity. Now we can supply all of them simultaneously at their design levels.”

The beamlines feed the Fermilab NOvA, MicroBooNE and MINERvA neutrino experiments and the Muon g-2 experiment. Researchers have been happy to have more particles coming their way.

“The science we do depends heavily on beam performance and the operators who keep the beam running day and night,” said William & Mary physicist Tricia Vahle, co-spokesperson for the NOvA neutrino experiment. “This year NOvA saw the strongest evidence yet for a subtle phenomenon, a type of antineutrino oscillation. Without the spectacular, intense stream of particles coming from the lab complex, we wouldn’t have been able to detect it without running the experiment much longer.”

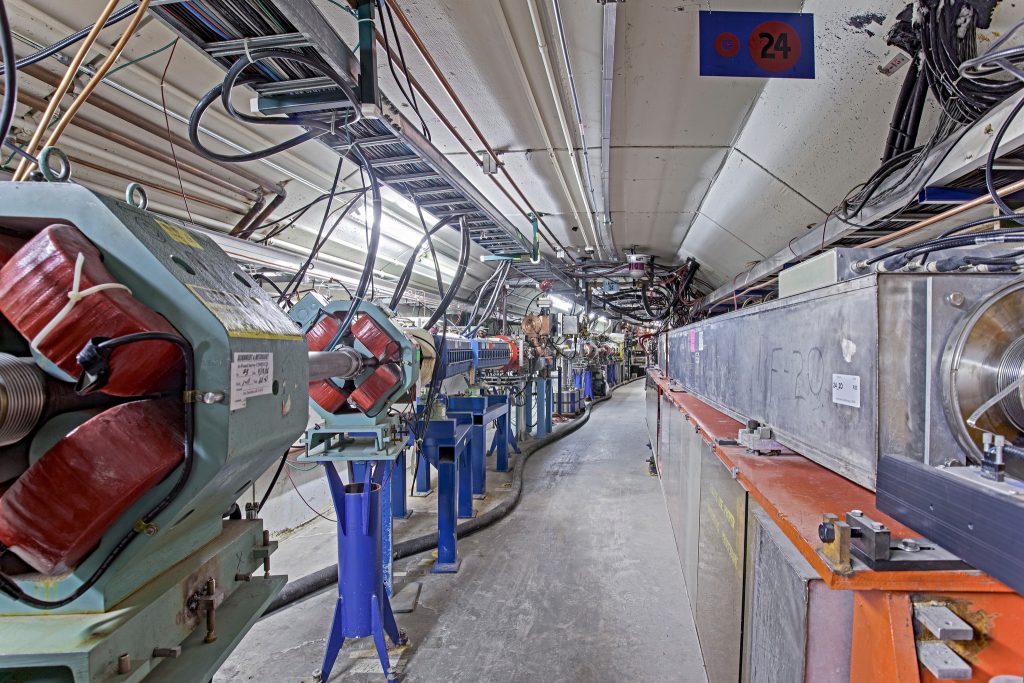

The Fermilab Booster accelerator delivers beam to all of the lab’s accelerator-based experiments. Photo: Marty Murphy

That’s intense

Just as you can assess the quality of a diamond by its carat, clarity and color, you can size up a particle beam according to a few criteria — reliability, efficiency and intensity.

Intensity is key. With every additional proton you squeeze into a beam, you create another opportunity for scientists to study the workings of the subatomic world. That’s critical for physicists studying rare phenomena who need as many particles as they can get.

At Fermilab, the proton beam smashes into a bit of material called a target, producing other particles that scientists then study. Two of these other particles are of keen interest at Fermilab: neutrinos and muons. They clue us in to the nature of the vacuum that pervades space-time and how the universe evolved.

But scientists need lots of them to get to the bottom of these mysteries. And that means lots of protons.

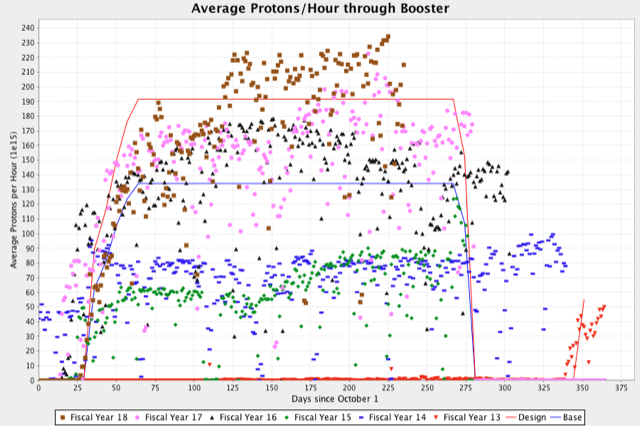

Earlier this year, after undergoing a major overhaul, the Fermilab Booster set an intensity record. It produced 240 million billion protons on target per hour. This record proton flux (the number of particles that pass a given point over a period of time) was more than two times what it was previously.

“It’s all about flux,” Pellico said. “How much beam can you get? How many protons can we hit the target with? It’s been a complete change in how we approach beam, going from the high energies of the previous lab era — the Tevatron era — to high intensities.”

One factor that increased the flux was a higher repetition rate. Before, the Booster fired beam about eight times a second. Now it’s nearly double that, at 15.

“If we hadn’t increased our rep rate, we’d be able to supply just one of the beamlines and no other,” said Duane Newhart of Fermilab accelerator operations. “It’s all about having enough beam to spread around.”

One of the Booster’s beneficiaries is the Muon g-2 experiment, which aims to measure a particular property of muons to high precision.

“High-intensity beams are crucial for us — for all the rare-physics experiments,” said Fermilab scientist Chris Polly, Muon g-2 co-spokesperson. “It’s a tall order to send beams to multiple experiments, especially when they’re all hungry for particles.”

The average Booster beam intensity has climbed steadily year after year, thanks to upgrades to the lab’s accelerator complex. The brown data points are from 2018; the pink from 2017, and the black from 2016. Image courtesy of Paul Derwent

Such high efficiency!

As particles travel through an accelerator, some wander from the pack and become lost to the surrounding equipment. An ongoing challenge for accelerator experts is to reduce this loss by drawing on every trick in the book of accelerator science.

The Booster team set out to crank up the intensity while keeping losses in check.

Multiple improvements to the accelerator chain, including the installation of a new instrument called a laser notcher, kept losses under control.

“We doubled the intensity, but the losses haven’t increased one bit,” Pellico said.

“We did so many things to make it happen, and saying one was the key component would be a mistake,” Newhart said. “It all worked together. And now we are pushing more protons through than we ever have.”

Rely on it

A powerful proton beam is an incredible tool for discovery — when it’s on. The greater the accelerator’s so-called up time — the fraction of time an accelerator spends in operation mode — the more beam experiments get.

The upgraded Booster’s up time is at a record 92 percent, compared to 89 percent before upgrades.

“It’s become even more reliable, and it’s one of the oldest machines in the complex,” Pellico said. “We keep improving it. We want the machine to be viable and reliable for at least the next 15 years.”

Fermilab experiments take beam around the clock, and when particles interact only once in a blue moon — neutrinos are famously reluctant to react — beam availability matters.

“Neutrino experiments notoriously need a lot of beam in order to be able to carry out their science objectives. The Fermilab complex consistently delivers beam with high reliability. Fermilab is the place to do neutrino physics,” said Fermilab physicist Sam Zeller, co-spokesperson for the MicroBooNE neutrino experiment, which recently produced its first collection of physics results. “We are extremely thankful to Fermilab’s incredible team of accelerator physicists and operators.”

Beam me up, Booster

The Booster records are the outcome of six years of Proton Improvement Plan upgrades, a hard-earned achievement by the Fermilab accelerator teams.

“The first part of this year, we just kept pushing that Booster record up and up and up,” Newhart said.

The team plans to go up and up to higher intensities still. Under the next accelerator upgrade phase, called Proton Improvement Plan II, accelerator experts will improve parts of the complex, including the installation of new linear accelerator, to provide even more powerful proton beams.

The megawatt-scale protons — 60 percent more powerful than what is currently available — will be sent to future experiments coming online within the next few years: the Short-Baseline Neutrino Program and the Mu2e muon experiment.

The higher-power beams will also be sent to the international Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility and Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, scheduled to come online in the late 2020s. The Fermilab-hosted LBNF/DUNE will be the largest neutrino oscillation experiment ever built, sending particles 800 miles from Fermilab, in Illinois, to a giant detector one mile underground in South Dakota.

“This whole time we’ve gotten to understand the Booster a little better, the beam physics a little better. Last year’s work really paved the way for our future work under PIP-II,” Pellico said. “Soon it will be time to break some more records.”

And we can always use a little more beam.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC, a joint partnership between the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association Inc. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

UPDATE: July 9, 2018, 6:05 p.m.

Acid leak contained, clean-up begins

Fire department hazardous-material personnel successfully contained a pinhole-sized leak of sulfuric acid from a 400-gallon tank used for water treatment in a building on the Fermilab site and stopped the leak. A hazardous-material contractor is now on site to remove the acid remaining in the tank and clean up the area where the leak occurred.

There was no environmental impact.

POSTED July 9, 4:02 p.m.

What happened?

A 400-gallon tank with sulfuric acid for water treatment at Fermilab sprang a leak Monday afternoon, July 9, 2018, around 2:30 p.m., and is slowly leaking acid.

Who was involved?

Employee responsible for the system noticed the leak and informed Fermilab Fire Department. No people injured.

Where?

Tank located in Fermilab Central Utility Building.

What is the response?

Fermilab has requested support from local fire departments to contain leak and monitor situation. Fermilab fire department and local fire departments are at site of incident.

Background:

Sulfuric acid is a common chemical used in many processes. It is corrosive.

How will we provide further updates?

Fermilab will provide more updates when available. Reporters should check the Fermilab website at www.fnal.gov or call 630-840-3351.