Lasers — used in medicine, manufacturing and made wildly popular by science fiction — are finding a new use in particle physics.

Fermilab scientists and engineers have developed a tool called a laser notcher, which takes advantage of the laser’s famously precise targeting abilities to do something unexpected: boost the number of particles that accelerators send to experiments. It’s cranked up the lab’s particle output considerably — by an incredible 15 percent — giving scientists more opportunities to study nature’s tiniest constituents.

“For such a new design, the laser notcher has been remarkably reliable,” said Fermilab engineer Bill Pellico, who manages one of the laboratory’s major accelerator upgrade programs, called the Proton Improvement Plan. “It’s already shown it will provide a considerable increase in the number of particles we can produce.”

The notcher increases particle production, counterintuitively, by removing particles from a particle beam.

Bunching out

The process of removing particles isn’t new. Typically, an accelerator generates a particle beam in bunches — compact packets that contain hundreds of millions of particles each. Imagine each bunch in a beam as a pearl on a strand. Bunches can be arranged in patterns according to the acceleration needs. Perhaps the needed pattern is an 80-bunch-long string followed by a three-bunch-long gap. Often, the best way to create the gap is to start with a regular, uninterrupted string of bunches and simply remove the unneeded ones.

But it isn’t so simple. Traditionally, beam bunches are kicked out by a fast-acting magnet, called a magnetic kicker. It’s a messy business: Particles fly off, strike beamline walls and generally create a subatomic obstacle course for the beam. While it’s not impossible for the beam to pass through such a scene, it also isn’t smooth sailing.

Accelerator experts refer to the messy phenomenon as beam loss, and it’s a measurable, predictable predicament. They accommodate it by holding back on the amount of beam they accelerate in the first place, setting a ceiling on the number of particles they pack into the beam.

That ceiling is a limitation for Fermilab’s new and upcoming experiments, which require greater and greater numbers of particles than the accelerator complex could handle previously. So the lab’s accelerator specialists look for ways to raise the particle beam ceiling and meet the experimental needs for beam.

The most straightforward way to do this is to eliminate the thing that’s keeping the ceiling low and stifling particle delivery — beam loss.

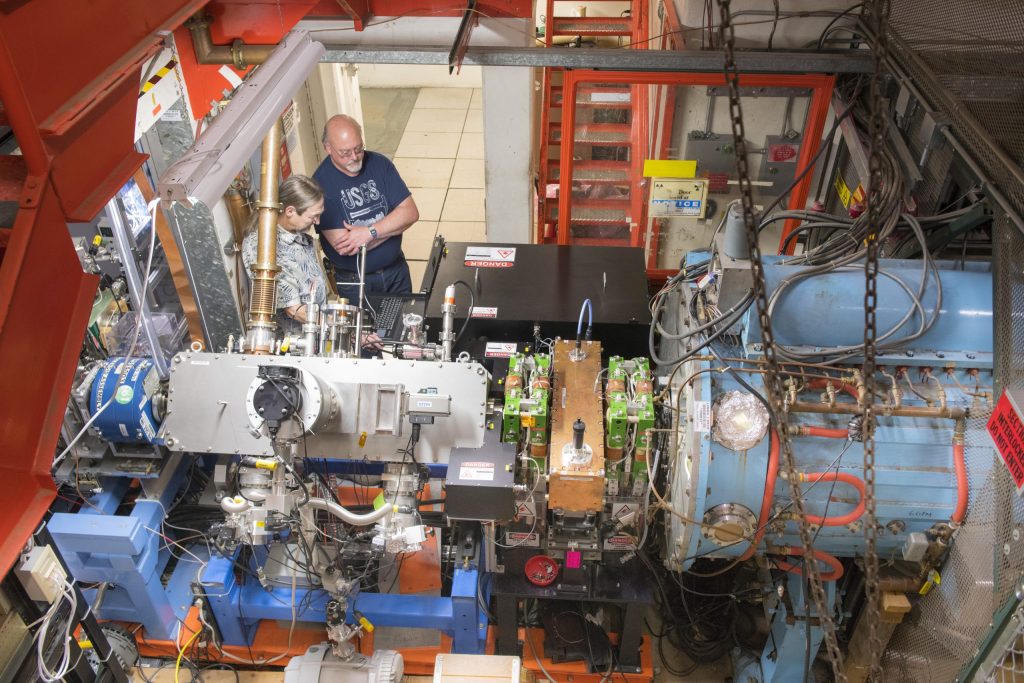

David Johnson, left, and Todd Johnson work on the recently installed laser notcher in the Fermilab accelerator complex. The laser notcher, the first application of its kind in an in-production particle accelerator, has helped boost particle beam production at the lab. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Lasers against loss

The new laser notcher works by directing powerful pulses of laser light at particle bunches, taking them out of commission. Both the position and precision of the notcher allow it to create gaps cleanly —delivering a one-two punch in curbing beam loss.

First, the notcher is positioned early in the series of Fermilab’s accelerators, when the particle beam hasn’t yet achieved the close-to-light speeds it will attain by the time it exits the accelerator chain. (At this early stage, the beam lumbers along at 4 percent the speed of light, a mere 2.7 million miles per hour.) This far upstream, the beam loss resulting from ejecting bunches doesn’t have much of an impact.

“We moved the process to a place where, when we lose particles, it really doesn’t matter,” said David Johnson, Fermilab engineering physicist who led the laser notcher project.

Second, the laser notcher is, like a scalpel, surgical in its bunch removal. It ejects bunches precisely, individually, bunch by bunch. That enables scientists to create gaps of exactly the right lengths needed by later acceleration stages.

For Fermilab’s accelerator chain, the winning formula is for the notcher to create a gap that is 80 nanoseconds (billionths of a second) long every 2,200 nanoseconds. It’s the perfect-length gap needed by one of Fermilab’s later-stage accelerators, called the Booster.

A graceful exit

The Fermilab Booster feeds beam to the next accelerator stages or directly to experiments.

Prior to the laser notcher’s installation, a magnetic kicker would boot specified bunches as they entered the Booster, resulting in messy beam loss.

With the laser notcher now on the scene, the Booster receives a beam that has prefab, well-defined gaps. These 80-nanosecond-long windows of opportunity mean that, as the beam leaves the Booster and heads toward its next stop, it can make a clean, no-fuss, no-loss exit.

With Booster beam loss brought down to low levels, Fermilab accelerator operators can raise the ceiling on the numbers of particles they can pack into the beam. The results so far are promising: The notcher has already allowed beam power to increase by a whopping 15 percent.

Thanks to this innovation and other upgrade improvements, the Booster accelerator is now operating at its highest efficiency ever and at record-setting beam power.

“Although lasers have been used in proton accelerators in the past for diagnostics and tests, this is the first-of-its-kind application of lasers in an operational proton synchrotron, and it establishes a technological framework for using laser systems in a variety of other bunch-by-bunch applications, which would further advance the field of high-power proton accelerators,” said Sergei Nagaitsev, head of the Fermilab Office of Accelerator Science Programs.

Plentiful protons and other particles

The laser notcher, installed in January, is a key part of a larger program, the Proton Improvement Plan (PIP), to upgrade the lab’s chain of particle accelerators to produce powerful proton beams.

As the name of the program implies, it starts with protons.

Fermilab sends protons barreling through the lab’s accelerator complex, and they’re routed to various experiments. Along the way, some of them are transformed into other particles needed by experiments, for example into neutrinos—tiny, omnipresent particles that could hold the key to filling in gaps in our understanding the universe’s evolution. Fermilab experiments need boatloads of these particles to carry out its scientific program. Some of the protons are transformed into muons, which can provide scientists with hints about the nature of the vacuum.

With more protons coming down the pipe, thanks to PIP and the laser notcher, the accelerator can generate more neutrinos, muons and other particles, feeding Fermilab’s muon experiments, Muon g-2 and Mu2e, and its neutrino experiments, including its largest operating neutrino experiment, NOvA, and its flagship, the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment and Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility.

“Considering all the upgrades and improvements to Fermilab accelerators as a beautiful cake with frosting, the increase in particle production we managed to achieve with the laser notcher is like the cherry on top of the cake,” Nagaitsev said.

“It’s a seemingly small change with a significant impact,” Johnson said.

As the Fermilab team moves forward, they’ll continue to put the notcher through its paces, investigating paths for improvement.

With this innovation, Fermilab adds another notch in the belt of what lasers can do.

Editor’s note: This article was revised on June 27, 2018.

Scientists study tiny particles called neutrinos to learn about how our universe evolved. These particles, well-known for being tough to detect, could tell the story of how matter won out over antimatter a fraction of a second after the Big Bang and, consequently, why we’re here at all.

Getting to the bottom of that split-second history means uncovering the differences, if any, between the neutrino and its antimatter counterpart, the antineutrino.

The MINERvA neutrino experiment at Fermilab recently added some detail to the behavior profiles of neutrinos and antineutrinos: Scientists measured the likelihood that these famously fleeting particles would stop in the MINERvA detector. In particular, they looked at cases in which an antineutrino interacting in the detector produced another particle, a neutron — that familiar particle that, along with the proton, makes up an atom’s nucleus.

MINERvA’s studies of such cases benefit other neutrino experiments, which can use the results to refine their own measurements of similar interactions.

It’s typical to study the particles produced by the interaction of a neutrino (or antineutrino) to get a bead on the neutrino’s behavior. Neutrinos are effortless escape artists, and their Houdini-like nature makes it difficult to measure their energies directly. They sail unimpeded through everything — even lead. Scientists are tipped off to the rare neutrino interaction by the production of other, more easily detected particles. They measure and sum the energies of these exiting particles and thus indirectly measure the energy of the neutrino that kicked everything off.

This particular MINERvA study — antineutrino enters, neutron leaves — is a difficult case. Most postinteraction particles deposit their energies in the particle detector, leaving tracks that scientists can trace back to the original antineutrino (or neutrino, as the case may be).

But in this experiment, the neutron doesn’t. It holds on to its energy, leaving almost none in the detector. The result is a practically untraceable, unaccounted energy that can’t easily be entered in the energy books. And unfortunately, antineutrinos are good at producing energy-absconding neutrons.

Researchers make the best of missing-energy situations. They predict, based on other studies, how much energy is lost and correct for it.

To give the scientific community a data-based, predictive tool for missing-energy moments, MINERvA collected data from the worst-case situation: An antineutrino strikes a nucleus in the detector and knocks out the untraceable neutron so nearly all of the energy bestowed to the nucleus goes “poof.” (These interactions also produce positively charged particles called muons which signal the antineutrino interaction.) By studying this particular disappearing act, scientists could directly measure the effects of the missing energy.

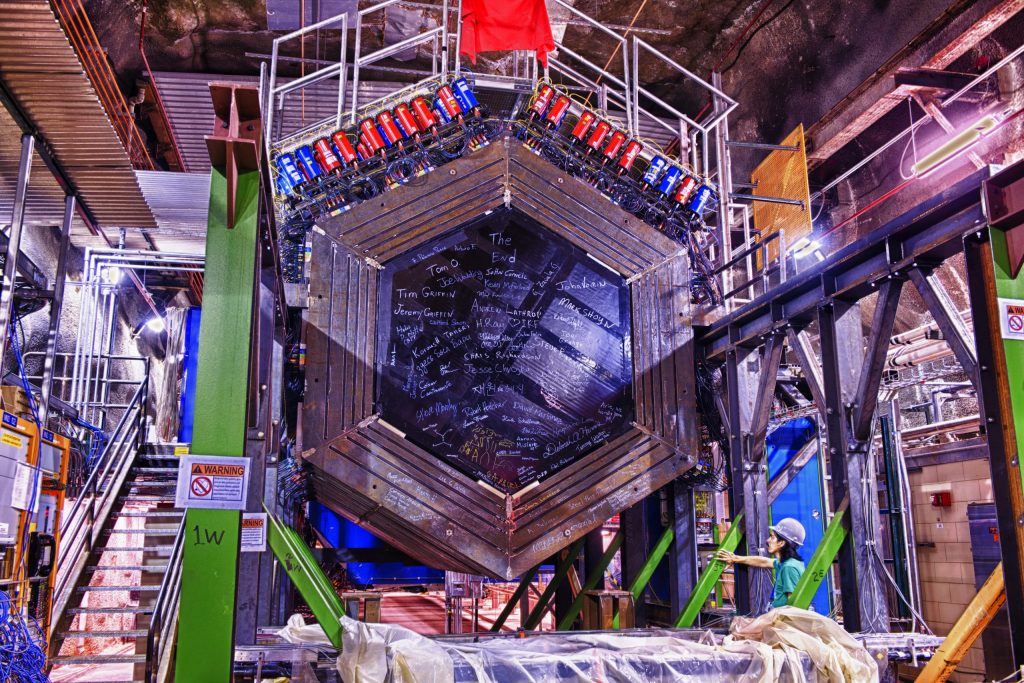

Scientists at Fermilab use the MINERvA to make measurements of neutrino interactions that can support the work of other neutrino experiments. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Other researchers can now look for these effects, applying the lessons learned to similar cases. For example, researchers on Fermilab’s largest operating neutrino experiment, NOvA, and the Japanese T2K experiment will use this technique in their antineutrino measurements. And the Fermilab-hosted international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, centerpiece of a world-leading neutrino program, will also benefit from this once it begins collecting data in the 2020s.

The neutron production case is just one type of missing-energy interaction, one of many. So the model that comes out of this MINERvA study is an admittedly imperfect one. There can’t be a one-size-fits-all-missing-energy-scenarios model. But it still provides a useful tool for piecing together a neutrino’s energy — and that’s a tough task no matter what particles come out of the interaction.

“This analysis is a great testament to both the detector’s ability to measure neutrino interactions and to the collaboration’s ability to develop new strategies,” said Fermilab scientist and MINERvA co-spokesperson Deborah Harris. “When we started MINERvA, this analysis was not even a gleam in anyone’s eye.”

There’s a bonus to this recent study, too, one that bolsters an investigation conducted last year.

For the earlier investigation, MINERvA focused on neutrino (instead of antineutrino) interactions that knocked out proton-neutron pairs (instead of lone neutrons or protons). In a detector such as MINERvA, a proton’s energy is much easier to measure than a neutron’s, so the earlier study presumably yielded more precise measurements than the recent antineutrino study.

How good were these measurements? MINERvA scientists plugged the values of the earlier neutrino study into a model of this recent antineutrino study to see what would pop out. Lo and behold, the adjustment to the antineutrino model improved its ability to predict the data.

The combination of the two studies gives the neutrino physics community new information about how well models do and where they fall short. Searches for the phenomenon known as CP violation — the thing that makes matter special compared to antimatter and enabled it to conquer in the post-Big Bang battle — depend on comparing neutrino and antineutrino samples and looking for small differences. Large, unknown differences between neutrino and antineutrino reaction products would hide the presence or absence of CP signatures.

“We are no longer worried about large differences, and our neutrino program can work with small adjustments to known differences,” said University of Minnesota–Duluth physicist Rik Gran, lead author on this result.

MINERvA is homing in on models that, with each new test, better describe both neutrino and antineutrino data — and thus the story of how the universe came to be.

These results appeared on June 1, 2018, in Physical Review Letters.