Scientists working on the Short-Baseline Near Detector at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have identified the detector’s first neutrino interactions.

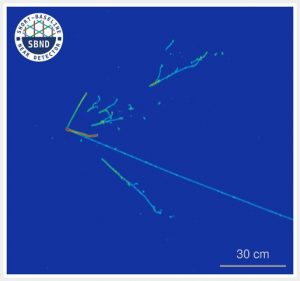

Display of a candidate muon neutrino interaction observed by the Short-Baseline Near Detector. When a neutrino enters SBND and interacts with an argon nucleus, it creates a spray of charged particles that the detector records. Physicists can then work backwards from these secondary particles to where the neutrino interaction occurred. Credit: SBND collaboration

The SBND collaboration has been planning, prototyping and constructing the detector for nearly a decade. And, after a few-months-long process of carefully turning on each of the detector subsystems, the moment they’d all been waiting for finally arrived.

“It isn’t every day that a detector sees its first neutrinos,” said David Schmitz, co-spokesperson for the SBND collaboration and associate professor of physics at the University of Chicago. “We’ve all spent years working toward this moment and this first data is a very promising start to our search for new physics.”

SBND is the final element that completes Fermilab’s Short-Baseline Neutrino (SBN) Program and will play a critical role in solving a decades old mystery in particle physics. Getting SBND to this point has been an international effort. The detector was built by an international collaboration of 250 physicists and engineers from Brazil, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The Standard Model is the best theory for how the universe works at its most fundamental level. It is the gold standard particle physicists use to calculate everything from high-intensity particle collisions in particle accelerators to very rare decays. But despite being a well-tested theory, the Standard Model is incomplete. And over the past 30 years, multiple experiments have observed anomalies that may hint at the existence of a new type of neutrino.

Neutrinos are the second most abundant particle in the universe. Despite being so abundant, they’re incredibly difficult to study because they only interact through gravity and the weak nuclear force, meaning they hardly ever show up in a detector.

Neutrinos come in three types, or flavors: muon, electron and tau. Perhaps the strangest thing about these particles is that they change among these flavors, oscillating from muon to electron to tau.

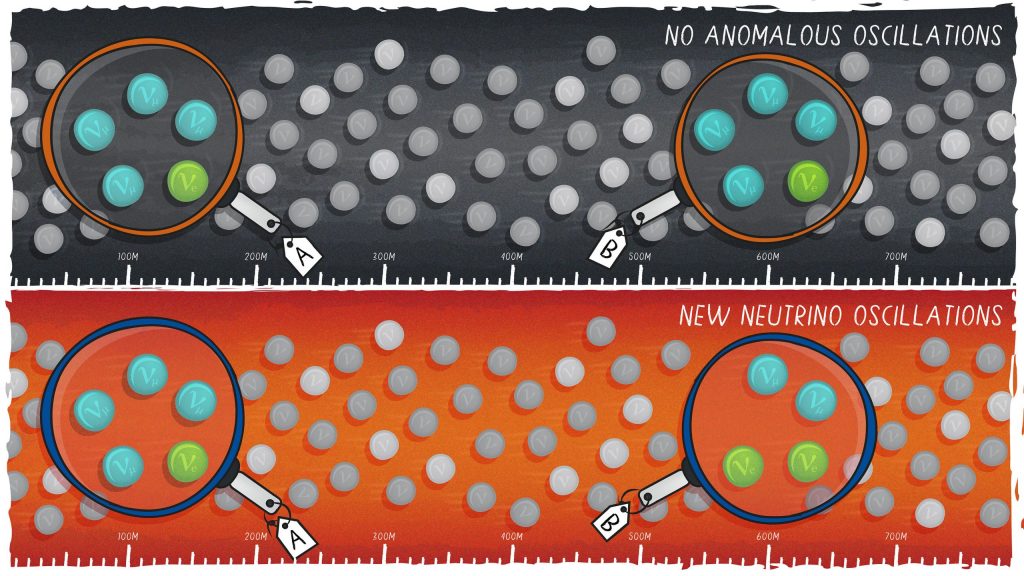

Scientists have a pretty good idea of how many of each type of neutrino should be present at different distances from a neutrino source. Yet observations from a few previous neutrino experiments disagreed with those predictions.

Our current understanding of neutrinos predicts that the number and type of neutrinos detected at points A and B should be the same. However, various neutrino experiments have observed anomalies in the number and type of neutrinos at a distance corresponding to point B. The Short-Baseline Near Detector and a second detector called ICARUS have been placed at points A and point B, respectively, to search for such nonstandard oscillations. Credit: Samantha Koch, Fermilab.

“That could mean that there’s more than the three known neutrino flavors,” explained Fermilab scientist Anne Schukraft. “Unlike the three known kinds of neutrinos, this new type of neutrino wouldn’t interact through the weak force. The only way we would see them is if the measurement of the number of muon, electron and tau neutrinos is not adding up like it should.”

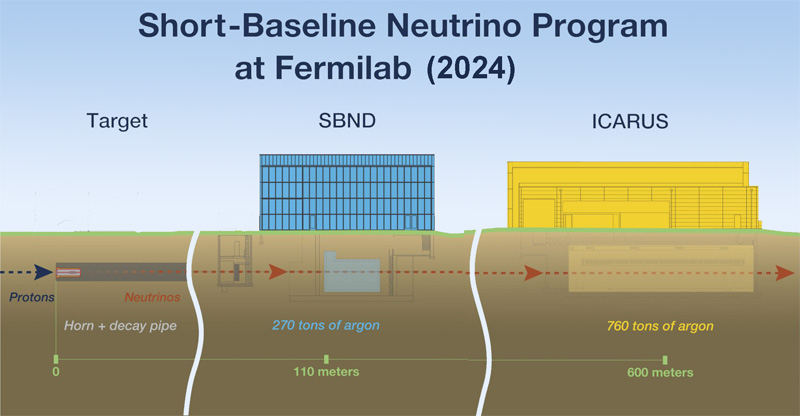

The Short Baseline Neutrino Program at Fermilab will perform searches for neutrino oscillation and look for evidence that could point to this fourth neutrino. SBND is the near detector for the Short Baseline Neutrino Program while ICARUS, which started collecting data in 2021, is the far detector. A third detector called MicroBooNE finished recording particle collisions with the same neutrino beamline that same year.

The Short-Baseline Near Detector and ICARUS are the near and far detectors, respectively, in the Short-Baseline Neutrino Program. Credit: Fermilab

The Short Baseline Neutrino Program at Fermilab differs from previous short-baseline measurements with accelerator-made neutrinos because it features both a near detector and far detector. SBND will measure the neutrinos as they were produced in the Fermilab beam and ICARUS will measure the neutrinos after they’ve potentially oscillated. So, where previous experiments had to make assumptions about the original composition of the neutrino beam, the SBN Program will definitively know.

“Understanding the anomalies seen by previous experiments has been a major goal in the field for the last 25 years,” said Schmitz. “Together SBND and ICARUS will have outstanding ability to test the existence of these new neutrinos.”

Beyond the hunt for new neutrinos

In addition to searching for a fourth neutrino alongside ICARUS, SBND has an exciting physics program on its own.

Because it is located so close to the neutrino beam, SBND will see 7,000 interactions per day, more neutrinos than any other detector of its kind. The large data sample will allow researchers to study neutrino interactions with unprecedented precision. The physics of these interactions is an important element of future experiments that will use liquid argon to detect neutrinos, such as the long-baseline Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, known as DUNE.

Whenever a neutrino collides with the nucleus of an atom, the interaction sends a spray of particles careening through the detector. Physicists need to account for all the particles produced during that interaction, both those visible and invisible, to infer the properties of the ghostly neutrinos.

It’s relatively easy to model what happens with simple nuclei, like helium and hydrogen, but SBND, like many modern neutrino experiments, uses argon to trap neutrinos. The nucleus of an argon atom consists of 40 nucleons, making interactions with argon more complex and more difficult to understand.

“We will collect 10 times more data on how neutrinos interact with argon than all previous experiments combined,” said Ornella Palamara, Fermilab scientist and co-spokesperson for SBND. “So, the analyses that we do will be also very important for DUNE.”

But neutrinos won’t be the only particles SBND scientists will keep an eye out for. With the detector located so close to the particle beam, it’s possible that the collaboration could see other surprises.

“There could be things, outside of the Standard Model, that have nothing to do with neutrinos but are produced as a byproduct of the beam that the detector would be able to see,” said Schukraft.

One of the biggest questions the Standard Model doesn’t have an answer for is dark matter. Although SBND would only be sensitive to lightweight particles, those theoretical particles could provide a first glimpse at a ‘dark sector’.

“So far ‘direct’ dark matter searches for massive particles haven’t turned anything up,” said Andrzej Szelc, SBND physics co-coordinator and professor at the University of Edinburgh. “Theorists have devised a whole plethora of dark sector models of lightweight dark particles that could be produced in a neutrino beam and SBND will be able to test whether these models are true.”

The Short-Baseline Neutrino Detector collaboration celebrated the moment the detector began running at 100% voltage. Credit: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

These neutrino signatures are only the beginning for SBND. The collaboration will continue operating the detector and analyzing the many millions of neutrino interactions collected for the next several years.

“Seeing these first neutrinos is the start of a long process that we have been working towards for years,” said Palamara. “This moment is the beginning of a new era for the collaboration.”

The Short-Baseline Near Detector international collaboration is hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The collaboration consists of 38 partner institutions, including national labs and universities from five countries. SBND is one of two particle detectors in the Short-Baseline Neutrino Program that provides information on a beam of neutrinos created by Fermilab’s particle accelerators.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.