The world’s most precise measurement of the mass of the W boson, one of nature’s elementary particles, has been achieved by scientists from the CDF and DZero collaborations at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The new measurement is an important, independent constraint of the mass of the theorized Higgs boson. It also provides a rigorous test of the Standard Model that serves as the blueprint for our world, detailing the properties of the building blocks of matter and how they interact.

The Higgs boson is the last undiscovered component of the Standard Model and theorized to give all other particles their masses. Scientists employ two techniques to find the hiding place of the Higgs particle: the direct production of Higgs particles and precision measurements of other particles and forces that could be influenced by the existence of a Higgs particles. The new measurement of the W boson mass falls into the precision category.

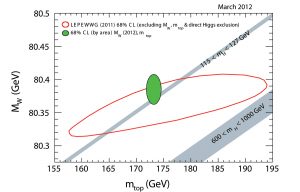

The CDF collaboration measured the W boson mass to be 80387 ± 19 MeV/c2. The DZero collaboration measured the particle’s mass to be 80375 ± 23 MeV/c2. The two measurements combined along with the addition of previous data from the earliest operation of the Tevatron produces a measurement of 80387 ± 17 MeV/c2, which has a precision of 0.02 percent.

These ultra-precise, rigorous measurements took up to five years for the collaborations to complete independently. The collaborations measured the particle’s mass in six different ways, which all match and combine for a result that is twice as precise as the previous measurement. The results were presented at seminars at Fermilab over the past two weeks by physicists Ashutosh Kotwal from Duke University and Jan Stark from the Laboratoire de Physique Subatomique et de Cosmologie in Grenoble, France.

“This measurement illustrates the great contributions that the Tevatron has made and continues to make with further analysis of its accumulated data,” said Fermilab Director Pier Oddone. “The precision of the measurement is unprecedented and allows rigorous tests of our underlying theory of how the universe works.”

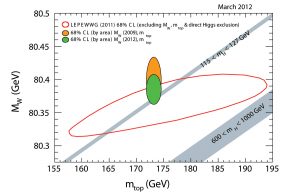

The new W mass measurement and the latest precision determination of the mass of the top quark from Fermilab triangulate the location of the Higgs particle and restrict its mass to less than 152 GeV/c2 .This is in agreement with the latest direct searches at the LHC, which constrain the Higgs mass to less than 127 GeV/c2, and direct-search limits from the Tevatron, which point to a Higgs mass of less than 156 GeV/c2, before the update of their results expected for next week.

“The Tevatron has expanded the way we view particle physics,” said CDF co-spokesperson and Fermilab physicist Rob Roser. “Tevatron experiments discovered the top quark, made precision measurements of the W boson mass, observed B_s mixing and set many limits on potential new physics theories.”

The new measurement comes at a pivotal time, just days before physicists from the Tevatron and the Large Hadron Collider at CERN will present their latest direct-search results in the hunt for the Higgs at the annual conference on Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories known as Rencontres de Moriond in Italy. The CDF and DZero experiments plan to present their latest results on Wednesday, March 7.

“It is a very exciting time to analyze data at particle colliders,” said Gregorio Bernardi, DZero co-spokesperson and physicist at the Laboratoire de Physique Nucléaire et de Hautes Energies in Paris. “The next few months will confirm if the Standard Model is correct, or if there are other particles and forces yet to be discovered.”

The existence of the world we live in depends on the W boson mass being heavy rather than massless as the Standard Model predicts. The W boson is a carrier of the electroweak nuclear force that is responsible for such fundamental process as the production of energy in the sun.

“The W mass is a very distinctive feature of the universe we live in, and requires an explanation,” said Giovanni Punzi, CDF co-spokesperson and physicist from the University of Pisa. “Its precise value is perhaps the most striking evidence for something “out there” still to be found, be it the Higgs or some variation of it.”

“The measurement of the W boson mass will be one of the great scientific legacies of the Tevatron particle collider,” added DZero co-spokesperson and Fermilab scientist Dmitri Denisov.

Notes for Editors:

Funding for the CDF and DZero experiments comes from DOE’s Office of Science, the U.S. National Science Foundation, and numerous international funding agencies.

CDF collaborating institutions are at http://www-cdf.fnal.gov/collaboration/index.html

DZero collaborating institutions are at http://www-d0.fnal.gov/ib/Institutions.html

Fermilab, America’s only national laboratory fully dedicated to particle physics research, is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

- Control room for CDF where particle sprays from collisions are analyzed.

- The Tevatron typically produces about 10 million proton-antiproton collisions per second. Each collision produces hundreds of particles. About 200 collisions per second are recorded at each detector for further analysis.

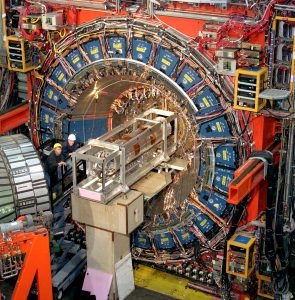

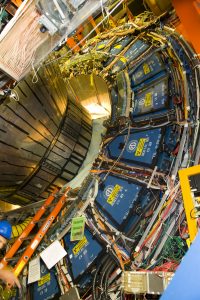

- The three-story, 6,000-ton CDF detector takes snapshots of the particles that emerge when protons and antiprotons collide.

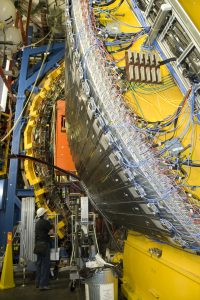

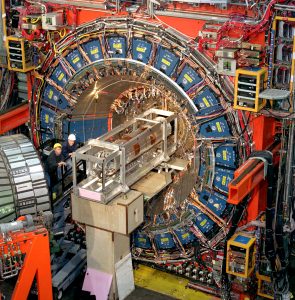

- Scientists measure the energy, momentum and electric charges of subatomic particles using a three-story assembly of sub detectors wrapped around DZero’s collision area like the layers of an onion.

- The 4-mile in circumference Tevatron accelerator at Fermilab uses superconducting magnets chilled to minus 450 degrees Fahrenheit, as cold as outer space, to move particles at nearly the speed of light.

- Control room for CDF where particle sprays from collisions are analyzed.

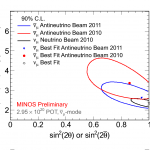

- The orange oval shows the previous CDF and DZero combined result for the W boson mass (vertical section of the oval), combined with the world’s best value for the top quark mass (horizontal section of the oval). The green oval shows the new result. The grey bar shows the remaining areas not ruled out for where the Higgs boson could reside.

- The three-story, 6,000-ton CDF detector takes snapshots of the particles that emerge when protons and antiprotons collide.

- Scientists measure the energy, momentum and electric charges of subatomic particles using a three-story assembly of sub detectors wrapped around DZero’s collision area like the layers of an onion.

- The new CDF and Dzero combined result for the W boson mass (vertical section of green oval), combined with the world’s best value for the top quark mass (horizontal section of green oval), restricts the Higgs mass requiring it to be less than 152 GeV/c2 with 95 percent probability. Direct searches have narrowed the allowed Higgs mass range to 115-127 GeV/c2. The grey bar shows the remaining area the Higgs could reside in.

Scientists at Fermilab and Berkeley Lab build the biggest map of dark matter yet, using methods that will improve ground-based surveys

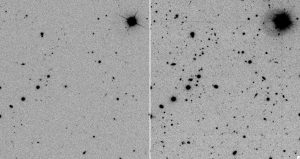

Teams from Fermilab and Berkeley Lab used galaxies from wide-ranging SDSS Stripe 82, a tiny detail of which is shown here, to plot new maps of dark matter based on the largest direct measurements of cosmic shear to date. Credit: SDSS.

BATAVIA, Illinois, and BERKELEY, California – Two teams of physicists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have independently made the largest direct measurements of the invisible scaffolding of the universe, building maps of dark matter using new methods that, in turn, will remove key hurdles for understanding dark energy with ground-based telescopes.

The teams’ measurements look for tiny distortions in the images of distant galaxies, called “cosmic shear,” caused by the gravitational influence of massive, invisible dark matter structures in the foreground. Accurately mapping out these dark-matter structures and their evolution over time is likely to be the most sensitive of the few tools available to physicists in their ongoing effort to understand the mysterious space-stretching effects of dark energy.

Both teams depended upon extensive databases of cosmic images collected by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), which were compiled in large part with the help of Berkeley Lab and Fermilab.

“These results are very encouraging for future large sky surveys. The images produced lead to a picture of the galaxies in the universe that is about six times fainter, or further back in time, than is available from single images,” says Huan Lin, a Fermilab physicist and member of the SDSS and the Dark Energy Survey (DES).

Layering photos of one area of sky taken at various time periods, a process called coaddition, can increase the sensitivity of the images six fold by removing errors and enhancing faint light signals. The image on the left show a single picture of galaxies from the SDSS Stripe 82 area of sky. The image on the right shows the same area with the layered effect, increasing the number of visible, distant galaxies. Credit: SDSS.

Melanie Simet, a member of the SDSS collaboration from the University of Chicago, will outline the new techniques for improving maps of cosmic shear and explain how these techniques can expand the reach of upcoming international sky survey experiments during a talk at 2 p.m. CST on Monday, January 9, at the American Astronomical Society (AAS) conference in Austin, Texas. In her talk she will demonstrate a unique way to analyze dark matter’s distortion of galaxies to get a better picture of the universe’s past.

Eric Huff, an SDSS member from Berkeley Lab and the University of California at Berkeley, will present a poster describing the full cosmic shear measurement, including the new constraints on dark energy, from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. CST Thursday, January 12, at the AAS conference.

Several large astronomical surveys, such as the Dark Energy Survey, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, and the HyperSuprimeCam survey, will try to measure cosmic shear in the coming years. Weak lensing distortions are so subtle, however, that the same atmospheric effects that cause stars to twinkle at night pose a formidable challenge for cosmic shear measurements. Until now, no ground-based cosmic-shear measurement has been able to completely and provably separate weak lensing effects from the atmospheric distortions.

“The community has been building towards cosmic shear measurements for a number of years now,” says Huff, an astronomer at Berkeley Lab, “but there’s also been some skepticism as to whether they can be done accurately enough to constrain dark energy. Showing that we can achieve the required accuracy with these pathfinding studies is important for the next generation of large surveys.”

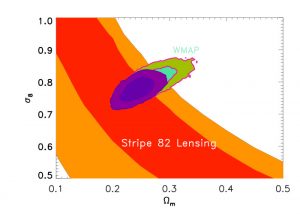

Constrains on cosmological parameters from SDSS Stripe 82 cosmic shear at the 1- and 2-sigma level. Also shown are the constraints from WMAP. The innermost region is the combined constrain from both WMAP and Stripe 82. Credit: SDSS.

To construct dark matter maps, the Berkeley Lab and Fermilab teams used images of galaxies collected between 2000 and 2009 by SDSS surveys I and II, using the 2.5-meter SLOAN telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. The galaxies lie within a continuous ribbon of sky known as SDSS Stripe 82, lying along the celestial equator and encompassing 275 square degrees. The galaxy images were captured in multiple passes over many years.

The two teams layered snapshots of a given area taken at different times, a process called coaddition, to remove errors caused by the atmospheric effects and to enhance very faint signals coming from distant parts of the universe. The teams used different techniques to model and control for the atmospheric variations and to measure the lensing signal, and have performed an exhaustive series of tests to prove that these models work.

Gravity tends to pull matter together into dense concentrations, but dark energy acts as a repulsive force that slows down the collapse. Thus the clumpiness of the dark matter maps provides a measurement of the amount of dark energy in the universe.

When they compared their final results before the AAS meeting, both teams found somewhat less structure than would have been expected from other measurements such as the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), but, says Berkeley Lab’s Huff, “the results are not yet different enough from previous experiments to ring any alarm bells.”

Meanwhile, says Lin, “Our image-correction processes should prove a valuable tool for the next generation of weak-lensing surveys.”

Fermilab/ University of Chicago scientific papers:

- coadd data: http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.6619

- photometric redshifts: http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.6620

- cluster lensing: http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.6621

- cosmic shear: http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.6622

Berkeley Lab/ University of California at Berkeley scientific papers:

- coadd data: http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.6958

- cosmic shear: http://arxiv.org/abs/1112.3143

Note for Editors:

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

Fermilab is a national laboratory supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

The National Science Foundation supported this research. For more information, please visit http://www.nsf.gov/.

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey is the most ambitious survey of the sky ever undertaken, involving more than 300 astronomers and engineers at 25 institutions around the world. SDSS-II, which began in 2005 and finished observations in July, 2008, is comprised of three complementary projects.

Funding for the SDSS and SDSS-II has been provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Participating Institutions, the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Japanese Monbukagakusho, the Max Planck Society, and the Higher Education Funding Council for England. The SDSS Web Site is http://www.sdss.org/.

Batavia, Ill. — A new accelerator research facility being built at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory will bolster Illinois’ reputation as a technology hub and foster job creation.

Officials broke ground for the Illinois Accelerator Research Center at Fermilab Dec. 16. From left: Bob Kephart, IARC Project Director; Jim Siegrist, associate director of the Office of Science for the Office of High Energy Physics; Michael Weis, DOE Fermilab site manager for the Office of Science; William Brinkman, director of the Office of Science for the DOE; Pier Oddone, Fermilab director; Warren Ribley, director of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity; Linda Holmes, Illinois state senator; and Michael Fortner, Illinois state representative.

The Illinois Accelerator Research Center (IARC) at the Department of Energy’s Fermilab will provide a state-of-the-art facility for research, development and industrialization of particle accelerator technology. The design and construction of IARC is jointly funded by DOE and the State of Illinois.

“In Illinois we understand the importance of investing in cutting edge technologies, which not only boost our economy, but also secure our role as a major competitor in the global marketplace,” said Governor Quinn. “The best minds in the world are right here, and today we are investing in our future by ensuring that the latest groundbreaking particle research activities will continue to come from Illinois.”

A major focus of IARC will be to develop partnerships with private industry for the commercial and industrial application of accelerator technology for energy and the environment, medicine, industry, national security and discovery science. IARC will also offer unique advanced educational opportunities to a new generation of Illinois engineers and scientists and attract top scientists from around the world.

Located in the heart of the industrial area of the Fermilab campus, IARC will house 42,000 square feet of technical, office and educational space for scientists and engineers from Fermilab, DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, local universities and industrial partners.

“The IARC facility will help fuel innovation by developing advanced technologies, strengthening ties with industry and training the scientists of tomorrow,” said Dr. William F. Brinkman, Director of DOE’s Office of Science, one of the speakers at today’s groundbreaking. “The Department of Energy welcomes the opportunity to partner with the State of Illinois and looks forward to seeing IARC come to fruition.”

The superstars of the particle accelerator world are the giant research accelerators such as the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland and Fermilab’s Tevatron, which was permanently shut down in September. Behind the headlines, about 30,000 accelerators are at work around the world in industry, medicine, security, defense and science. All the products that are processed, treated or inspected by particle beams have an estimated annual value of more than $500 billion.

Today’s particle accelerators address many of the challenges confronting our nation in the areas of sustainable energy, a cleaner environment, economic security, health care and national defense. The accelerators of tomorrow have the potential to make still greater contributions. Other nations are already applying these next-generation technologies to current-generation issues, and challenging U.S. leadership in accelerator innovation. The U.S., which has traditionally led the world in the development and application of accelerator technology, now finds its leadership threatened.

“A focused effort and strengthened partnerships between government and industry are required for the United States to remain competitive in accelerator science and technology,” said Fermilab Director Pier Oddone. “IARC will greatly enhance accelerator research and innovation at Fermilab and strengthen our capability to host new international projects. We will also broaden our economic impact on Illinois by working with industry and universities on advanced R&D with many commercial and scientific applications.”

The Illinois Jobs Now! capital bill provided $20 million to the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity to fund a grant for the design and construction of a new building that will form part of the IARC complex.

“The IARC facility positions Illinois at the forefront of the world-wide effort to develop cutting-edge accelerator technologies,” said Warren Ribley, Director of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, another speaker at today’s groundbreaking. “It also reinforces the Quinn Administration’s commitment to supporting innovation in Illinois, as well as the creation of 200 high-tech jobs in addition to construction jobs.”

The DOE is also providing $13 million to Fermilab to refurbish an existing heavy industrial building that will be incorporated into the complex, adding 36,000 square feet of specialized workspace.

More information about the Illinois Accelerator Research Center is available at: http://www.fnal.gov/pub/IARC

To learn more about the applications of particle accelerators, visit: http://www.acceleratorsamerica.org/

Fermilab is a national laboratory supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC.

The Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity raises Illinois’ profile as a global business destination and nexus of innovation. It provides a foundation for the economic prosperity of all Illinoisans, through the coordination of business recruitment and retention, infrastructure building and job training efforts, and administration of state and federal grant programs.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the Unites States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov.

BATAVIA, Illinois — Two experiments at the Large Hadron Collider have nearly eliminated the space in which the Higgs boson could dwell, scientists announced in a seminar held at CERN today. However, the ATLAS and CMS experiments see modest excesses in their data that could soon uncover the famous missing piece of the physics puzzle.

The experiments revealed the latest results as part of their regular report to the CERN Council, which provides oversight for the laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland.

Theorists have predicted that some subatomic particles gain mass by interacting with other particles called Higgs bosons. The Higgs boson is the only undiscovered part of the Standard Model of physics, which describes the basic building blocks of matter and their interactions.

The experiments’ main conclusion is that the Standard Model Higgs boson, if it exists, is most likely to have a mass constrained to the range 116-130 GeV by the ATLAS experiment, and 115-127 GeV by CMS. Tantalising hints have been seen by both experiments in this mass region, but these are not yet strong enough to claim a discovery.

Higgs bosons, if they exist, are short-lived and can decay in many different ways. Just as a vending machine might return the same amount of change using different combinations of coins, the Higgs can decay into different combinations of particles. Discovery relies on observing statistically significant excesses of the particles into which they decay rather than observing the Higgs itself. Both ATLAS and CMS have analysed several decay channels, and the experiments see small excesses in the low mass region that has not yet been excluded .

Taken individually, none of these excesses is any more statistically significant than rolling a die and coming up with two sixes in a row. What is interesting is that there are multiple independent measurements pointing to the region of 124 to 126 GeV. It’s far too early to say whether ATLAS and CMS have discovered the Higgs boson, but these updated results are generating a lot of interest in the particle physics community.

Hundreds of scientists from U.S. universities and institutions are heavily involved in the search for the Higgs boson at LHC experiments, said CMS physicist Boaz Klima of the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory near Chicago. “U.S. scientists are definitely in the thick of things in all aspects and at all levels,” he said.

More than 1,600 scientists, students, engineers and technicians from more than 90 U.S. universities and five U.S. national laboratories take part in the CMS and ATLAS experiments, the vast majority via an ultra-high broadband network that delivers LHC data to researchers at universities and national laboratories across the nation . The Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation provide support for U.S. participation in these experiments. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is the host laboratory for the U.S. contingent on the CMS experiment, while Brookhaven National Laboratory hosts the U.S. ATLAS collaboration.

Over the coming months, both the CMS and ATLAS experiments will focus on refining their analyses in time for the winter particle physics conferences in March. The experiments will resume taking data in spring 2012.

“We’ve now analyzed all or most of the data taken in 2011 in some of the most important Higgs search analyses,” said ATLAS physicist Rik Yoshida of Argonne National Laboratory near Chicago. “I think everybody’s very surprised and pleased at the pace of progress.”

Higgs-hunting scientists on experiments at U.S. particle accelerator the Tevatron will also present results in March.

Discovering the type of Higgs boson predicted in the Standard Model would confirm a theory first put forward in the 1960s.

Even if the experiments find a particle where they expect to find the Higgs, it will take more analysis and more data to prove it is a Standard Model Higgs. If scientists found subtle departures from the Standard Model in the particle’s behavior, this would point to the presence of new physics , linked to theories that go beyond the Standard Model. Observing a non-Standard Model Higgs, currently beyond the reach of the LHC experiments with the data they’ve recorded so far , would immediately open the door to new physics .

Another possibility, discovering the absence of a Standard Model Higgs , would point to new physics at the LHC’s full design energy, set to be achieved after 2014. Whether ATLAS and CMS show over the coming months that the Standard Model Higgs boson exists or not, the LHC program is closing in on new discoveries.

Notes for editors:

Media contacts:

Brookhaven National Laboratory – Karen McNulty Walsh, kmcnulty@bnl.gov, 631-344-8350

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory – Tona Kunz, tkunz@fnal.gov, 630-840-3351

Information about the US participation in the LHC is available at http://www.uslhc.us. Follow US LHC on Twitter at twitter.com/uslhc.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is operated and managed for DOE’s Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates and Battelle. Visit Brookhaven Lab’s electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more: http://www.bnl.gov/newsroom.

Fermilab is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory, operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

The National Science Foundation focuses its LHC support on funding the activities of U.S. university scientists and students on the ATLAS, CMS and LHCb detectors, as well as promoting the development of advanced computing innovations essential to address the data challenges posed by the LHC. For more information, please visit http://www.nsf.gov/.

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, is the world’s leading laboratory for particle physics. It has its headquarters in Geneva. At present, its Member States are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Romania is a candidate for accession. Israel is an Associate Member in the pre-stage to Membership. India, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States of America, Turkey, the European Commission and UNESCO have Observer status.

Photos:

Click here for photos.

Background videos and information:

What is a Higgs boson? http://www.youtube.com/user/fermilab#p/u/3/RIg1Vh7uPyw

How do we search for Higgs bosons?

http://www.youtube.com/user/fermilab#p/u/0/1GrqMCz_vnA

Backgrounders on the Higgs boson search:

http://press.web.cern.ch/press/background/B01-Higgs_en.html

http://press.web.cern.ch/press/background/B10-Higgs_evolution_or_revolution_en.html

Definitions of important terms: http://press.web.cern.ch/press/background/B09-Important_Higgs_terms_en.html

Videos from CERN (available at 9:30 a.m. CST, 10:30 a.m. EST):

A roll: https://cdsweb.cern.ch/record/1406052

B roll: https://cdsweb.cern.ch/record/1406051

Further information:

From ATLAS: http://www.atlas.ch/news/2011/status-report-dec-2011.html

From CMS: http://cms.web.cern.ch/news/cms-search-standard-model-higgs-boson-lhc-data-2010-and-2011

The Tevatron will shut down at the end of September 2011 after 26 years of colliding particles. The two detector teams that utilize the Tevatron, CDF and DZero, will continue to analyze data and produce scientific papers at the same record-setting rate for the next couple of years and then at a slower rate for another two years.

The steadily increasing data sets at the Tevatron have boosted the number of papers submitted by the CDF and DZero collaborations collectively for publication in 2011 up from a life-time average of one a week. At a little more than six months through 2011, both collaborations have published more than 60 papers between them and are on track to publish more papers in a single year than any year in the history of the Tevatron experiments. The number of publications produced will grow through 2012 and beyond as scientists will use better analysis techniques to squeeze more information out of their unique data sets.

CDF and DZero explore the subatomic world to search for the origin of mass, extra dimensions of space and new particles that could explain the nature of our universe. Nearly 1,000 students have received Ph.D.s through their research at the Tevatron.

See this pdf to get highlights of discoveries and technological advances made possible by the Tevatron.

The shutdown process

The laboratory will celebrate the accomplishments of the Tevatron, its detectors and those who made and operate them with a ceremony Sept. 30. Media may have access in person or online to this event. Notifications will be made closer to Sept. 30.

When the Tevatron shuts down no one will do anything as dramatic as pull a plug. Accelerator operators will simply stop putting stores of protons and antiprotons into the Tevatron ring. The last store will be utilized until it’s collision per second rate drops below a useful level and then the remaining particles will be harmlessly diverted into a metal target that will absorb them. This is a routine process that has been used for annual maintenance shutdowns. Accelerator operators will then warm up the superconducting magnets in the accelerator tunnel for a few days to a week. After that, crews will slowly start removing the fluids and gases. That work should be finished by the end of December.

As for the detectors, CDF will have its fluids and gases removed within a month and be completely shut down. DZero will take about three months because the collaboration plans to take cosmic-ray data for a brief period to do a double-check of the calibration of its detector before fully shutting it down.

Tevatron

The 4-mile in circumference Tevatron accelerator uses superconducting magnets chilled to minus 450 degrees Fahrenheit, as cold as outer space, to move particles at nearly the speed of light.

The Tevatron typically produces about 10 million proton-antiproton collisions per second. Each collision produces hundreds of particles. About 200 collisions per second are recorded at each detector for further analysis.

As of July 2011, CDF has analyzed more than 8 inverse femtobarns of collision data while DZero has scrutinized up to 9 inverse femtobarns. The collaborations anticipate accumulating a total of 10 and 11 inverse femtobarns of data, respectively, by the time the Tevatron shuts down at the end of September. One inverse femtobarn represents about 50 trillion proton-antiproton collisions at the Tevatron.

CDF

The three-story, 6,000-ton CDF detector takes snapshots of the particles that emerge when protons and antiprotons collide. The CDF collaboration consists of about 500 members from 63 institutions in 15 countries.

DZero

Scientists measure the energy, momentum and electric charges of subatomic particles using a three-story assembly of sub detectors wrapped around DZero’s collision area like the layers of an onion. About 500 physicists from 90 institution in 18 countries work on DZero.

Main Control Room

Accelerator operators working 24-hours-a-day maintain a “sweet spot” level of protons and antiprotons and steer them through a chain of seven accelerators, culminating in the Tevatron ring, that increase the speed of the particles like gears on a car. The system creates and contains for the longest amount of time the most antimatter in the world.

Tevatron Milestone

January 1973

Fermilab establishes superconducting magnet R&D program

July 5, 1979

DOE authorizes Fermilab to build superconducting accelerator

March 18, 1983

Installation of the last of 774 superconducting magnets

Video

July 3, 1983

Tevatron accelerates protons to world record energy of 512 GeV

https://history.fnal.gov/lml_tevatron.html#saver

August 16, 1983

Groundbreaking for Antiproton Source

Video

October 1, 1983

Start of the Tevatron fixed-target program at 400 GeV with five fixed-target experiments

https://conferences.fnal.gov/tevft/book/SECTION9.htm

February 16, 1984

Acceleration of Tevatron beam to 800 GeV.

September 6, 1985

Fermilab accelerators produce and collect (“stack”) first antiprotons

October 13, 1985

First observation of proton-antiproton collisions by CDF collider detector

at 1.6 TeV (2 x 800 GeV)

Video

May 1986

Tevatron named one of the Top Ten Engineering Achievements of the Last 100 Years

October 21, 1986

Acceleration of Tevatron beam to 900 GeV

November 30, 1986

First proton-antiproton collisions at 1.8 TeV

October 18, 1989

President George Bush presents Helen Edwards, Dick Lundy, Rich Orr and Alvin Tollestrup with the National Medal of Technology for their work in building the Tevatron.

https://history.fnal.gov/wh_fermilab.html#1989

May 12, 1992

DZero collider detector observes first proton-antiproton collisions

https://d0server1.fnal.gov/projects/results/runi/highlights/highlight_document/Highlights_v18_final.pdf

August 31, 1992:

Collider Run I begins

September 27, 1993

Tevatron’s cryogenic cooling system is named International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers

Video | Graphic

February 2, 1995

Tevatron sets world record for number of high-energy proton-antiproton particle collisions.

March 3, 1995

Experimenters of the CDF and DZero collaborations announce discovery of top quark.

Learn more | Video

February 20, 1996

End of Collider Run I. The Tevatron has delivered 180 inverse picobarns to both CDF and DZero.

Learn more | Video

November 18, 1996

Observation of antihydrogen atoms at Fermilab

Learn more | Video

August 5, 1997

The Tevatron delivers a record intensity 800 GeV beam for fixed-target experiments: 2.86E13.

March 5, 1998

Discovery of B-sub-c Meson, the last of the quark-antiquark pairs known to exist.

March 1, 1999

Observation of direct CP violation in the decay of neutral Kaons

January 2000

End of the Tevatron fixed-target program, which provided beam to 43 experiments

July 20, 2000

The DONuT experiment reports first evidence for the direct observation of the tau neutrino

March 1, 2001

Start of Tevatron Collider Run 2

July 16, 2004

Tevatron achieves a peak luminosity of 1E32 cm -2sec -1.

June 24, 2005:

Run 2 achieves one inverse femtobarn of integrated luminosity

July 9, 2005

First observation of electron cooling of antiprotons in the Recycler Ring

February 10, 2006

The Antiproton Source exceeds for the first time a stacking rate of 20 mA per hour

September 25, 2006

Discovery of B_s matter-antimatter oscillations: 3 trillion times per second

October 23, 2006

Discovery of Sigma-sub-b baryons (u-u-b and d-d-b)

January 7, 2007

CDF announces the most precise measurement of the W boson mass by a single experiment

June 2007

Discovery of the cascade-b baryon (down-strange-bottom combination)

March 17, 2008

The Tevatron achieves a peak luminosity in excess of 3E32 cm -2sec -1.

March 25, 2008

The Tevatron delivers 50 inverse picobarns in a single week

July 30, 2008

Observation of ZZ diboson production at the Tevatron

August 4, 2008

Tevatron experiments start restricting the allowed Higgs mass range

https://www.fnal.gov/pub/presspass/press_releases/Higgs-constraints-August2008.html

September 2008

Both CDF and DZero reach five inverse femtobarns of luminosity

March 9, 2009

Discovery of single top quark production

March 11, 2009

DZero announces the world’s best measurement of W boson mass

March 18, 2009:

Discovery of a new quark structure named Y(4140)

June 29, 2009

Discovery of the Omega-sub-b baryon

https://www.fnal.gov/pub/presspass/press_releases/CDF-Omega-observation.html

July 20, 2011

Discovery of the Xi-sub-b, a heavy relative of the neutron

https://www.fnal.gov/pub/presspass/press_releases/2011/CDF-Xi-sub-b-observation-20110720.html

Sept. 30, 2011

Tevatron produces final proton-antiproton collisions; experiments will have collected about 10 inverse femtobarns of data each; data analysis will continue for several years

https://www.fnal.gov/pub/presspass/press_releases/2011/Tevatron-Shutdown-20100726-images.html

BATAVIA, Illinois — The physics community got a jolt last year when results showed for the first time that neutrinos and their antimatter counterparts, antineutrinos, might be the odd man out in the particle world and have different masses. This idea was something that went against most commonly accepted theories of how the subatomic world works.

A result released today (August 25) from the MINOS experiment at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory appears to quell concerns raised by a MINOS result in June 2010 and brings neutrino and antineutrino masses more closely in sync.

By bringing measurements of neutrinos and antineutrinos closer together, this new MINOS result allows physicists to lessen the potential ramifications of this specific neutrino imbalance. These ramifications include: a new way neutrinos interact with other particles, unseen interactions between neutrinos and matter in the earth and the need to rethink everything known about how the universe works at the tiniest levels.

“This more precise measurement shows us that these particles and their antimatter partners are very likely not as different as indicated earlier. Within our current range of vision it now seems more likely that the universe is behaving the way most people think it does,” said Rob Plunkett, Fermilab scientist and co-spokesman of MINOS. “This new, additional information on antineutrino parameters helps put limits on new physics, which will continue to be searched for by future planned experiments.”

University College London Physics Professor and MINOS co-spokesperson Jenny Thomas presented this new result — the world’s best measurement of muon neutrino and antineutrino mass comparisons — at the International Symposium on Lepton Photon Interactions at High Energies in Mumbai, India.

MINOS nearly doubled its data set since its June 2010 result from 100 antineutrino events to 197 events. While the new results are only about one standard deviation away from the previous results, the combination rules out concerns that the previous results could have been caused by detector or calculation errors. Instead, the combined results point to a statistical fluctuation that has lessened as more data is taken.

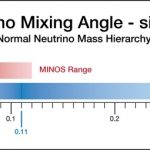

Physicists measured the differences between the squared masses between two types of neutrinos and compared them to the squared masses between two types of antineutrinos, a quantity called delta m squared. The 2010 result found, as a whole, that the range of mass difference in the neutrinos was about 40 percent less for antineutrinos, while the new result found a 16 percent difference.

“The previous results left a 2 percent chance that the neutrino and antineutrino masses were the same. This disagrees with what theories of how neutrinos operate predicted,” Thomas said. “So we have spent almost a year looking for some instrumental effect that could have caused the difference. It is comforting to know that statistics were the culprit.”

Because several neutrino experiments operating and planned across the globe rely on neutrino and antineutrino measurements being the same as part of their calculations, the new MINOS result hopefully removes a potential hurdle for them.

Fermilab’s accelerator complex is capable of producing intense beams of either muon antineutrinos or muon neutrinos to send to the two MINOS detectors, one at Fermilab and one in Minnesota. This capability allows the experimenters to measure the mass difference parameters. The measurement also relies on the unique characteristics of the MINOS far detector, particularly its magnetic field, which allows the detector to separate the positively and negatively charged muons resulting from interactions of antineutrinos and neutrinos, respectively.

The antineutrinos’ extremely rare interactions with matter allow most of them to pass through the Earth unperturbed. A small number, however, interact in the MINOS detector, located 735 km away from Fermilab in Soudan, Minnesota. During their journey, which lasts 2.5 milliseconds, the particles oscillate in a process governed by a difference between their mass states.

Further analysis will be needed by the upcoming Fermilab neutrino experiments NOvA and MINOS+ to close the mass difference even more. Both experiments will use an upgraded accelerator beam generated at Fermilab that will emit more than double the number of neutrinos. This upgraded beam is expected to start operating in 2013.

The MINOS experiment involves more than 140 scientists, engineers, technical specialists and students from 30 institutions, including universities and national laboratories, in five countries: Brazil, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Funding comes from: the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation in the U.S., the Science and Technology Facilities Council in the U.K; the University of Minnesota in the U.S.; the University of Athens in Greece; and Brazil’s Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo (FAPESP) and National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Fermilab is a national laboratory supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

- Scientists know that there exist three types of neutrinos and three types of antineutrinos. Cosmological observations and laboratory-based experiments indicate that the masses of these particles must be extremely small: Each neutrino and antineutrino must weigh less than a millionth of the weight of an electron.

- This graph demonstrates that the new MINOS antineutrino result (blue) is more precise than last year’s result (red), as reflected by the smaller oval, and the new result is in better agreement with the mass range of the 2010 neutrino result (black), reflected by the overlap of the blue and red ovals. The ovals represent the 90 percent statistical confidence levels for each result. A 90 percent confidence level means that if scientists were to repeat the measurement many times, they would expect to obtain a result that lies within the contour 90 percent of the time. The points inside the ovals show the best, or most likely, value for each of the three measurements. The best value for the 2011 measurement of the squared mass difference for the antineutrinos is 2.62 x 10-3 eV2.

- Neutrinos, ghost-like particles that rarely interact with matter, travel 450 miles straight through the earth from Fermilab to Soudan — no tunnel needed. The Main Injector Neutrino Oscillation Search (MINOS) experiment studies the neutrino beam using two detectors. The MINOS near detector, located at Fermilab, records the composition of the neutrino beam as it leaves the Fermilab site. The MINOS far detector, located in Minnesota, half a mile underground, again analyzes the neutrino beam. This allows scientists to directly study the oscillation of muon neutrinos into electron neutrinos or tau neutrinos under laboratory conditions.

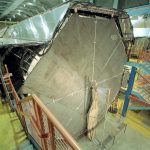

- The MINOS far detector is located in a cavern half a mile underground in the Soudan Underground Laboratory, Minnesota. The 100-foot-long MINOS far detector consists of 486 massive octagonal planes, lined up like the slices of a loaf of bread. Each plane consists of a sheet of steel about 25 feet high and one inch thick, with the last one visible in the photo. The whole detector weighs 6,000 tons. Since March 2005, the far detector has recorded neutrinos from a beam produced at Fermilab. The MINOS collaboration records about 1,000 neutrinos per year.

- The 1,000-ton MINOS near detector sits 350 feet underground at Fermilab. The detector consists of 282 octagonal-shaped detector planes, each weighing more than a pickup truck. Scientists use the near detector to verify the intensity and purity of the muon neutrino beam leaving the Fermilab site. Photo: Peter Ginter

- Fermilab completed the construction and testing of the Neutrino at the Main Injector (NuMI) beam line in early 2005. Protons from Fermilab’s Main Injector accelerator (left) travel 1,000 feet down the beam line, smash into a graphite target and create muon neutrinos. The neutrinos traverse the MINOS near detector, located at the far end of the NuMI complex, and travel straight through the earth to a former iron mine in Soudan, Minnesota, where they cross the MINOS far detector. Some of the neutrinos arrive as electron neutrinos or tau neutrinos.

- When operating at highest intensity, the NuMI beam line transports a package of 35,000 billion protons every two seconds to a graphite target. The target converts the protons into bursts of particles with exotic names such as kaons and pions. Like a beam of light emerging from a flashlight, the particles form a wide cone when leaving the target. A set of two special lenses, called horns (photo), is the key instrument to focus the beam and send it in the right direction. The beam particles decay and produce muon neutrinos, which travel in the same direction. Photo: Peter Ginter

- More than 140 scientists, engineers, technical specialists and students from Brazil, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States are involved in the MINOS experiment. This photo shows some of them posing for a group photo at Fermilab, with the 16-story Wilson Hall and the spiral-shaped MINOS service building in the background.

- Far view The University of Minnesota Foundation commissioned a mural for the MINOS cavern at the Soudan Underground Laboratory, painted onto the rock wall, 59 feet wide by 25 feet high. The mural contains images of scientists such as Enrico Fermi and Wolfgang Pauli, Wilson Hall at Fermilab, George Shultz, a key figure in the history of Minnesota mining, and some surprises. A description of the mural, painted by Minneapolis artist Joe Giannetti, is available here.

August 22, 2011 – Two experimental collaborations at the Large Hadron Collider, located at CERN laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, announced today that they have significantly narrowed the mass region in which the Higgs boson could be hiding.

The ATLAS and CMS experiments excluded with 95 percent certainty the existence of a Higgs over most of the mass region from 145 to 466 GeV. They announced the new results at the biennial Lepton-Photon conference, held this year in Mumbai, India.

“Each time we add new data to our analyses, we close in more on where the Higgs might be hiding,” said Darin Acosta, a University of Florida professor and deputy physics coordinator for the CMS experiment.

More than 1,700 scientists, engineers and graduate students from the United States collaborate on the experiments at the LHC, most of them on the CMS and ATLAS experiments, through funding by the Department of Energy Office of Science and the National Science Foundation. Brookhaven National Laboratory serves as the U.S. base for participation in the ATLAS experiment, and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory serves as the U.S. base for participation in the CMS experiment.

The Higgs particle is the last not-yet-observed piece of the theoretical framework known as the Standard Model of particles and forces. According to the Standard Model, the Higgs boson explains why some particles have mass and others do not.

“The more data the experiments collect, the more scientists can say with greater statistical certainty,” said Konstantinos Nikolopoulos, a physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory on the ATLAS experiment. “The LHC has been providing that data at an impressive rate. The machine has been functioning beyond expectations.”

Scientists on ATLAS and CMS both announced seeing small, possible hints of the Higgs boson in the same mass range at the European Physical Society meeting in July. Those hints have become less pronounced as scientists have increased the amount of data in their analysis.

“These are exciting times for particle physics,” said CERN’s research director, Sergio Bertolucci. “Discoveries are almost assured within the next twelve months. If the Higgs exists, the LHC experiments will soon find it. If it does not, its absence will point the way to new physics.”

The experiments are on track to at least double the amount of data they have collected by the end of the year.

Notes for editors:

Media contacts:

Brookhaven National Laboratory – Kendra Snyder, ksnyder@bnl.gov, 631-344-8191

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory – Elizabeth Clements, lizzie@fnal.gov, 630-840-2326

Information about the US participation in the LHC is available at http://www.uslhc.us . Follow US LHC on Twitter at twitter.com/uslhc.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is operated and managed for DOE’s Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates and Battelle. Visit Brookhaven Lab’s electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more: http://www.bnl.gov/newsroom.

Fermilab is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory, operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at http://www.fnal.gov.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

The National Science Foundation focuses its LHC support on funding the activiites of U.S. university scientists and students on the ATLAS, CMS and LHCb detectors, as well as promoting the development of advanced computing innovations essential to address the data challenges posed by the LHC. For more information, please visit http://www.nsf.gov/.

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, is the world’s leading laboratory for particle physics. It has its headquarters in Geneva. At present, its Member States are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Romania is a candidate for accession. India, Israel, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States of America, Turkey, the European Commission and UNESCO have Observer status.

Batavia, Ill.— Experiments at the Department of Energy’s Fermilab are close to reaching the critical sensitivity that is necessary to look for the existence of a light Higgs particle. Scientists from both the CDF and DZero collider experiments at Fermilab will present their new Higgs search results at the EPS High-Energy Physics conference, held in Grenoble, France, from July 21-27.

The Higgs particle, if it exists, most likely has a mass between 114-137 GeV/c2, about 100 times the mass of a proton. This predicted mass range is based on stringent constraints established by earlier measurements, including the highest precision measurements of the top quark and W boson masses, made by Tevatron experiments. If the Higgs particle does not exist, Fermilab’s Tevatron experiments are on track to rule out this Higgs mass range in 2012.

If the Higgs particle does exist, then the Tevatron experiments may soon begin to find an excess of Higgs-like decay events. With the number of collisions recorded to date, the Tevatron experiments are currently unique in their ability to study the decays of Higgs particles into bottom quarks. This signature is crucial for understanding the nature and behavior of the Higgs particle.

“Both the DZero and CDF experiments have now analyzed about two-thirds of the data that we expect to have at the end of the Tevatron run on September 30,” said Stefan Soldner-Rembold, co-spokesperson of the DZero experiment. “In the coming months, we will continue to improve our analysis methods and continue to analyze our full data sets. The search for the Higgs boson is entering its most exciting, final stage.”

For the first time, the CDF and DZero collaborations have successfully applied well-established techniques used to search for the Higgs boson to observe extremely rare collisions that produce pairs of heavy bosons (WW or WZ) that decay into heavy quarks. This well-known process closely mimics the production of a W boson and a Higgs particle, with the Higgs decaying into a bottom quark and antiquark pair—the main signature that both Tevatron experiments currently use to search for a Higgs particle. This is another milestone in a years-long quest by both experiments to observe signatures that are increasingly rare and similar to the Higgs particle.

“This specific type of decay has never been measured before, and it gives us great confidence that our analysis works as we expect, and that we really are on the doorsteps of the Higgs particle,” said Giovanni Punzi, co-spokesperson for the CDF collaboration.

To obtain their latest Higgs search results, the CDF and DZero analysis groups separately sifted through more than 700,000 billion proton-antiproton collisions that the Tevatron has delivered to each experiment since 2001. After the two groups obtained their independent Higgs search results, they combined their results. Tevatron physicist Eric James will present the joint CDF-DZero search for the Higgs particle on Wednesday, July 27, at the EPS conference.

Scientists of the CDF collaboration at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory announced the observation of a new particle, the neutral Xi-sub-b (Ξb0). This particle contains three quarks: a strange quark, an up quark and a bottom quark (s-u-b). While its existence was predicted by the Standard Model, the observation of the neutral Xi-sub-b is significant because it strengthens our understanding of how quarks form matter. Fermilab physicist Pat Lukens, a member of the CDF collaboration, presented the discovery at Fermilab on Wednesday, July 20.

The neutral Xi-sub-b is the latest entry in the periodic table of baryons. Baryons are particles formed of three quarks, the most common examples being the proton (two up quarks and a down quark) and the neutron (two down quarks and an up quark). The neutral Xi-sub-b belongs to the family of bottom baryons, which are about six times heavier than the proton and neutron because they all contain a heavy bottom quark. The particles are produced only in high-energy collisions, and are rare and very difficult to observe.

Although Fermilab’s Tevatron particle collider is not a dedicated bottom quark factory, sophisticated particle detectors and trillions of proton-antiproton collisions have made it a haven for discovering and studying almost all of the known bottom baryons. Experiments at the Tevatron discovered the Sigma-sub-b baryons (Σb and Σb*) in 2006, observed the Xi-b-minus baryon (Ξb–) in 2007, and found the Omega-sub-b (Ωb–) in 2009. The lightest bottom baryon, the Lambda-sub-b (Λb), was discovered at CERN. Measuring the properties of all these particles allows scientists to test and improve models of how quarks interact at close distances via the strong nuclear force, as explained by the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). Scientists at Fermilab and other DOE national laboratories use powerful computers to simulate quark interactions and understand the properties of particles comprised of quarks.

Once produced, the neutral Xi-sub-b travels a fraction of a millimeter before it decays into lighter particles. These particles then decay again into even lighter particles. Physicists rely on the details of this series of decays to identify the initial particle. The complex decay pattern of the neutral Xi-sub-b has made the observation of this particle significantly more challenging than that of its charged sibling (Ξb–). Combing through almost 500 trillion proton-antiproton collisions produced by Fermilab’s Tevatron particle collider, the CDF collaboration isolated 25 examples in which the particles emerging from a collision revealed the distinctive signature of the neutral Xi-sub-b. The analysis established the discovery at a level of 7 sigma. Scientists consider 5 sigma the threshold for discoveries.

CDF also re-observed the already known charged version of the neutral Xi-sub-b in a never before observed decay, which served as an independent cross-check of the analysis. The newly analyzed data samples offer possibilities for further discoveries.

The CDF collaboration submitted a paper that summarizes the details of its Xi-sub-b discovery to the journal Physical Review Letters. It will be available on the arXiv preprint server on July 20, 2011.

CDF is an international experiment of about 500 physicists from 58 institutions in 15 countries. It is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and a number of international funding agencies.

Fermilab is a national laboratory funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC.

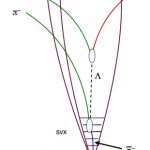

- Once produced, the neutral Xi-sub-b (Ξb0) particle travels about a millimeter before it disintegrates into two particles: the short-lived, positively charged Xi-sub-c (Ξc+) and a long-lived, negative pion (π-). The Xi-sub-c then promptly decays into a pair of long-lived pions and a Xi particle (Ξ–), which lives long enough to leave a track in the silicon vertex system (SVX) of the CDF detector before it decays a pion and a Lambda (Λ). The Lambda particle, which has no electric charge, can travel several centimeters before decaying into a proton (p) and a pion (π). Credit: CDF collaboration

- Baryons are particles made of three quarks. The quark model predicts the baryon combinations that exist with either spin J=1/2 (this graphic) or spin J=3/2 (not shown). The graphic shows the various three-quark combinations with J=1/2 that are possible using the three lightest quarks–up, down and strange–and the bottom quark. The CDF collaboration announced the discovery of the neutral Xi-sub-b (Ξb0), highlighted in this graphic. Experiments at Fermilab’s Tevatron collider have discovered all of the observed baryons with one bottom quark except the Lambda-sub-b, which was discovered at CERN. There exist additional baryons involving the charm quark, which are not shown in this graphic. The top quark, discovered at Fermilab in 1995, is too short-lived to become part of a baryon.

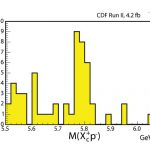

- The CDF collaboration has observed 25 Xi-sub-b candidates in their data. The analysis established the discovery of the neutral Xi-sub-b baryon at a level of 7 sigma. Scientists consider 5 sigma the threshold for discoveries. CDF scientists measured the mass of the neutral Xi-sub-b to be 5.7878 GeV/c2. Credit: CDF collaboration

- The Fermilab accelerator complex accelerates protons and antiprotons close to the speed of light. Converting energy into mass, the Tevatron collider can produce particles that are heavier than the protons and antiprotons that are colliding. The Tevatron produces millions of proton-antiproton collisions per second, maximizing the chance for discovery. Two experiments, CDF and DZero, search for new types of particles emerging from the collisions.

- The CDF detector, about the size of a 3-story house, weighs about 6,000 tons. Its subsystems record the “debris” emerging from high-energy proton-antiproton collisions. The detector surrounds the collision point and records the path, energy and charge of the particles emerging from the collisions. This information can be used to find and determine the properties of the Xi-sub-b particle.

- Some of the 500 scientists of the CDF collaboration in front of Wilson Hall at Fermilab.

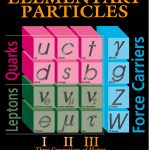

- Six quarks–up, down, strange, charm, bottom and top–are the building blocks of matter. Protons and neutrons are made of up and down quarks, held together by the strong nuclear force. The CDF experiment now has observed the neutral Xi-sub-b particle, which contains an up (u), strange (s) and bottom quark (b).

Scientists of the MINOS experiment at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory announced today (June 24) the results from a search for a rare phenomenon, the transformation of muon neutrinos into electron neutrinos. The result is consistent with and significantly constrains a measurement reported 10 days ago by the Japanese T2K experiment, which announced an indication of this type of transformation.

The results of these two experiments could have implications for our understanding of the role that neutrinos may have played in the evolution of the universe. If muon neutrinos transform into electron neutrinos, neutrinos could be the reason that the big bang produced more matter than antimatter, leading to the universe as it exists today.

The Main Injector Neutrino Oscillation Search (MINOS) at Fermilab recorded a total of 62 electron neutrino-like events. If muon neutrinos do not transform into electron neutrinos, then MINOS should have seen only 49 events. The experiment should have seen 71 events if neutrinos transform as often as suggested by recent results from the Tokai-to-Kamioka (T2K) experiment in Japan. The two experiments use different methods and analysis techniques to look for this rare transformation.

To measure the transformation of muon neutrinos into other neutrinos, the MINOS experiment sends a muon neutrino beam 450 miles (735 kilometers) through the earth from the Main Injector accelerator at Fermilab to a 5,000-ton neutrino detector, located half a mile underground in the Soudan Underground Laboratory in northern Minnesota. The experiment uses two almost identical detectors: the detector at Fermilab is used to check the purity of the muon neutrino beam, and the detector at Soudan looks for electron and muon neutrinos. The neutrinos’ trip from Fermilab to Soudan takes about one four hundredths of a second, giving the neutrinos enough time to change their identities.

For more than a decade, scientists have seen evidence that the three known types of neutrinos can morph into each other. Experiments have found that muon neutrinos disappear, with some of the best measurements provided by the MINOS experiment. Scientists think that a large fraction of these muon neutrinos transform into tau neutrinos, which so far have been very hard to detect, and they suspect that a tiny fraction transform into electron neutrinos.

The observation of electron neutrino-like events in the detector in Soudan allows MINOS scientists to extract information about a quantity called sin2 2θ13 (pronounced sine squared two theta one three). If muon neutrinos don’t transform into electron neutrinos, this quantity is zero. The range allowed by the latest MINOS measurement overlaps with but is narrower than the T2K range. MINOS constrains this quantity to a range between 0 and 0.12, improving on results it obtained with smaller data sets in 2009 and 2010. The T2K range for sin2 2θ13 is between 0.03 and 0.28.

“MINOS is expected to be more sensitive to the transformation with the amount of data that both experiments have,” said Fermilab physicist Robert Plunkett, co-spokesperson for the MINOS experiment. “It seems that nature has chosen a value for sin2 2θ13 that likely is in the lower part of the T2K allowed range. More work and more data are really needed to confirm both these measurements.”

The MINOS measurement is the latest step in a worldwide effort to learn more about neutrinos. MINOS will continue to collect data until February 2012. The T2K experiment was interrupted in March when the severe earth quake in Japan damaged the muon neutrino source for T2K. Scientists expect to resume operations of the experiment at the end of the year. Three nuclear-reactor based neutrino experiments, which use different techniques to measure sin2 2θ13, are in the process of starting up.

“Science usually proceeds in small steps rather than sudden, big discoveries, and this certainly has been true for neutrino research,” said Jenny Thomas from University College London, co-spokesperson for the MINOS experiment. “If the transformation from muon neutrinos to electron neutrinos occurs at a large enough rate, future experiments should find out whether nature has given us two light neutrinos and one heavy neutrino, or vice versa. This is really the next big thing in neutrino physics.”

The MINOS experiment involves more than 140 scientists, engineers, technical specialists and students from 30 institutions, including universities and national laboratories, in five countries: Brazil, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Funding comes from: the Department of Energy Office of Science and the National Science Foundation in the U.S., the Science and Technology Facilities Council in the U.K; the University of Minnesota in the U.S.; the University of Athens in Greece; and Brazil’s Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo (FAPESP) and National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Fermilab is a national laboratory supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy, operated under contract by Fermi Research Alliance, LLC.

For more information about MINOS and related experiments, visit the Fermilab neutrino website:

http://www.fnal.gov/pub/science/experiments/intensity/

- The building blocks of matter include three types of neutrinos, known as electron neutrino, muon neutrino and tau neutrino. For more than a decade, physicists have seen evidence that these neutrinos can transform into each other.

- The observation of electron neutrino-like events allows MINOS scientists to extract information about a quantity called sin22θ13. If muon neutrinos don’t transform into electron neutrinos, sin22θ13 is zero. The new MINOS result constrains this quantity to a range between 0 and 0.12, improving on results it obtained with smaller data sets in 2009 and 2010. The MINOS range is consistent with the T2K range for sin22θ13, which is between 0.03 and 0.28. According to the T2K data, the most likely value is 0.11. The MINOS result prefers a value of 0.04, and its data indicates that sin22θ13 is non-zero at the 89% confidence level.

- Neutrinos, ghost-like particles that rarely interact with matter, travel 450 miles straight through the earth from Fermilab to Soudan — no tunnel needed. The Main Injector Neutrino Oscillation Search (MINOS) experiment studies the neutrino beam using two detectors. The MINOS near detector, located at Fermilab, records the composition of the neutrino beam as it leaves the Fermilab site. The MINOS far detector, located in Minnesota, half a mile underground, again analyzes the neutrino beam. This allows scientists to directly study the oscillation of muon neutrinos into electron neutrinos or tau neutrinos under laboratory conditions.

- The MINOS far detector is located in a cavern half a mile underground in the Soudan Underground Laboratory, Minnesota. The 100-foot-long MINOS far detector consists of 486 massive octagonal planes, lined up like the slices of a loaf of bread. Each plane consists of a sheet of steel about 25 feet high and one inch thick, with the last one visible in the photo. The whole detector weighs 6,000 tons. Since March 2005, the far detector has recorded neutrinos from a beam produced at Fermilab. The MINOS collaboration records about 1,000 neutrinos per year.

- The 1,000-ton MINOS near detector sits 350 feet underground at Fermilab. The detector consists of 282 octagonal-shaped detector planes, each weighing more than a pickup truck. Scientists use the near detector to verify the intensity and purity of the muon neutrino beam leaving the Fermilab site. Photo: Peter Ginter

- Fermilab completed the construction and testing of the Neutrino at the Main Injector (NuMI) beam line in early 2005. Protons from Fermilab’s Main Injector accelerator (left) travel 1,000 feet down the beam line, smash into a graphite target and create muon neutrinos. The neutrinos traverse the MINOS near detector, located at the far end of the NuMI complex, and travel straight through the earth to a former iron mine in Soudan, Minnesota, where they cross the MINOS far detector. Some of the neutrinos arrive as electron neutrinos or tau neutrinos.

- When operating at highest intensity, the NuMI beam line transports a package of 35,000 billion protons every two seconds to a graphite target. The target converts the protons into bursts of particles with exotic names such as kaons and pions. Like a beam of light emerging from a flashlight, the particles form a wide cone when leaving the target. A set of two special lenses, called horns (photo), is the key instrument to focus the beam and send it in the right direction. The beam particles decay and produce muon neutrinos, which travel in the same direction. Photo: Peter Ginter

- More than 140 scientists, engineers, technical specialists and students from Brazil, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States are involved in the MINOS experiment. This photo shows some of them posing for a group photo at Fermilab, with the 16-story Wilson Hall and the spiral-shaped MINOS service building in the background.

- Far view The University of Minnesota Foundation commissioned a mural for the MINOS cavern at the Soudan Underground Laboratory, painted onto the rock wall, 59 feet wide by 25 feet high. The mural contains images of scientists such as Enrico Fermi and Wolfgang Pauli, Wilson Hall at Fermilab, George Shultz, a key figure in the history of Minnesota mining, and some surprises. A description of the mural, painted by Minneapolis artist Joe Giannetti, is available here.