How long have you worked at Fermilab?

I started in August/September 2016, so six years if I’m doing the math correctly.

What do you do at Fermilab?

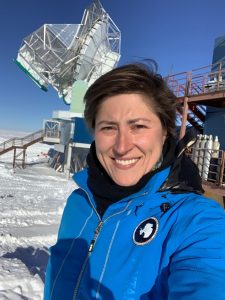

I’m an observational cosmologist with the Cosmic Physics Center. I work as a postdoctoral researcher on the South Pole Telescope; I do a lot of the control software and data analysis software work for SPT. We have a pretty complicated data pipeline. The telescope lives at the South Pole. We can’t get all our data back all at once, so there’s a lot of online data processing that we have to do. I handle a lot of that work and just making sure we don’t lose anything on the way here.

How did you first get interested in studying physics and the Cosmic Microwave Background?

I’ve always been sort of—it’s going to sound really cliché—fascinated with the big questions. When I was an undergrad, I did an exchange program in the U.K. with Cambridge University, and I did a project that involved looking at foregrounds. The Cosmic Microwave Background itself is actually well outside our own galaxy. There’s a lot of foregrounds in the way that are from within our own galaxy or other galaxies nearby, but mostly the ones in our own galaxy. I did a software project that was trying to work on methods of separating the foreground sky from the CMB, and it was interesting because it was my first big software project that I worked on. At the time, I was also working in a dark matter lab and building some instrumentation, and I wanted to combine those two interests.

When I went to grad school, my advisor basically roped me in and said, “I’m working on this telescope that’s going to be flown off the coast of Antarctica. Do you want to work on this telescope and study the Cosmic Microwave Background?” And I was like, “Yep, sounds great; sign me up.” That was a really cool project to work on: It’s called Spider; we launched it in January 2015. I’ve been doing Cosmic Microwave Background instrumentation for telescopes since then.

Does your work involve going to the South Pole to work on the telescope?

I went down to Antarctica to McMurdo Station for Spider, and then when I started this postdoc, I started going to the South Pole directly to work on SPT. For the first five years, it was just the summer season, so it’s a November-to-February timeframe when the weather is warm enough to be able to fly planes in and out. That’s when we do a lot of summer maintenance things, get our computing systems up and running, do upgrades to the electronics and hardware that we have there. It’s a really busy time, but really fun for the grad students to get to go down there and work with all of that.

Last year, I thought it would be a good time to do a whole year, so I took a leave of absence and spent the whole year, including the winter, at the South Pole. The station was closed with just 39 of us there from mid-February to mid-October 2021. It was myself and Matt Young; the two of us were the caretakers for SPT for the winter. We made sure the telescope kept running, all the data kept coming in, and nothing broke—pretty solid winter.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

The fact that this telescope is at the South Pole is super interesting for the public, so it’s really fun to be able to tell people about that and to get to go down there and show people what it’s like. The science is super interesting, and I find it pretty fun to engage with the public, talking about the Cosmic Microwave Background. It’s not too complicated to explain, even to kids.

Is there anything you find challenging in your work?

The hardest part of the project is that it’s so remote, so we have a lot of systems down there that are monitoring everything and people onsite year-round. Sometimes you run into a problem when you’re there that you can’t solve and you need to communicate with people up north about that. There’s a lot of preventative things that we try to do to make sure that the winter-overs are prepared to handle problems that come up. The trickiest thing to me is anticipating what could go wrong and fixing it before it becomes a real problem. I spend a lot of time making sure that if we run into a problem with the way the telescope is moving or the way we’re scheduling things that we nip it in the bud.

What do you like best about working at Fermilab?

Fermilab has a lot going on and good resources for getting stuff done. We’ve got a big space, and we’re able to do a bunch of device testing, hardware work and cryogenics. There’s also a lot of exposure to what other people are working on, so you’re not super isolated from the rest of the community that way.

What do you like to do for fun?

I play beach volleyball. There’s a pretty large beach volleyball community in Chicago and that’s how I like to spend my weekends.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Editor’s note: this press release was originally published by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Fermilab engineer Erik Voirin and then-Wilson fellow Hugh Lippincott designed and delivered the “xenon tower,” a package of cryogenic heat exchangers that continuously boils, purifies and recondenses the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment’s xenon, turning over the entire 10-ton payload every three days. Engineer Ian Young and Northwestern professor and Fermilab joint appointee Eric Dahl worked with the PPD Controls Group to build and program the 1,000-channel industrial control system.

Two Fermilab Lederman Fellows also played key roles in LZ’s world-leading result. Dylan Temples (MAGIS/QSC) spent his PhD measuring rare electron-capture backgrounds in liquid xenon with the Fermilab Noble R&D program. Kelly Stifter (SENSEI/QSC) spent her PhD at SLAC and her first year as a Lederman Fellow at Fermilab working to suppress and understand electron emission and the corresponding “accidental coincidence” backgrounds that have plagued recent competing experiments.

Deep below the Black Hills of South Dakota in the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF), an innovative and uniquely sensitive dark matter detector—the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment, led by Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab)—has passed a check-out phase of startup operations and delivered first results.

The take home message from this successful startup: “We’re ready and everything’s looking good,” said Berkeley Lab Senior Physicist and past LZ Spokesperson Kevin Lesko. “It’s a complex detector with many parts to it and they are all functioning well within expectations,” he said.

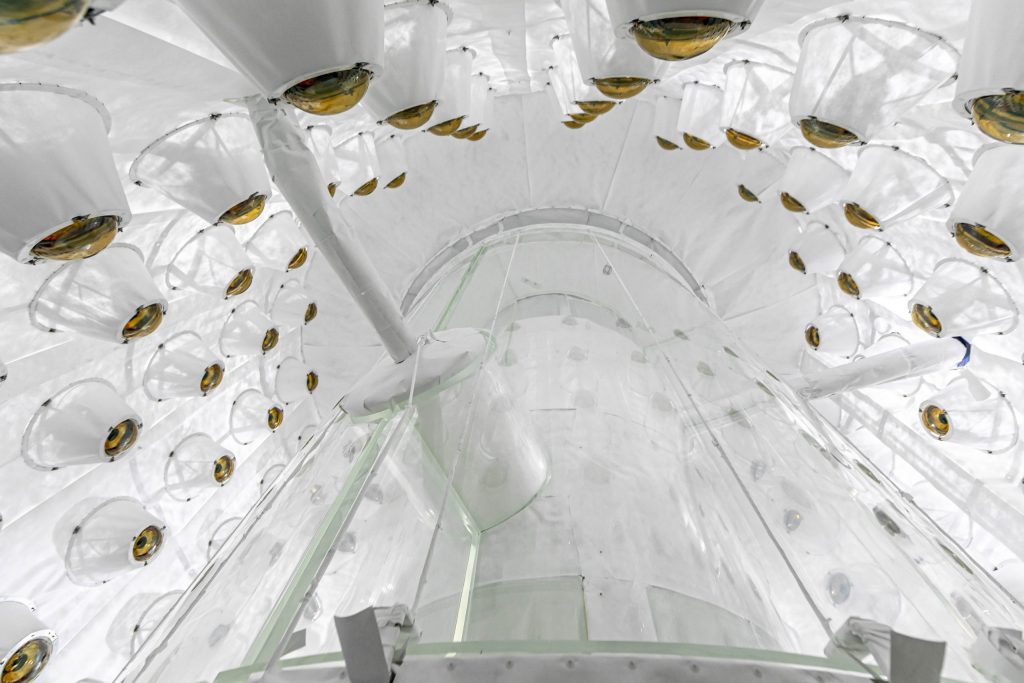

Looking up into the LZ Outer Detector, used to veto radioactivity that can mimic a dark matter signal. Credit: Matthew Kapust, Sanford Underground Research Facility

In a paper posted online today on the experiment’s website, LZ researchers report that with the initial run, LZ is already the world’s most sensitive dark matter detector. The paper will appear on the online preprint archive arXiv.org later today. LZ Spokesperson Hugh Lippincott of the University of California Santa Barbara said, “We plan to collect about 20 times more data in the coming years, so we’re only getting started. There’s a lot of science to do and it’s very exciting!”

Dark matter particles have never actually been detected—but perhaps not for much longer. The countdown may have started with results from LZ’s first 60 “live days” of testing. These data were collected over a three-and-a-half-month span of initial operations beginning at the end of December. This was a period long enough to confirm that all aspects of the detector were functioning well.

Unseen, because it does not emit, absorb, or scatter light, dark matter’s presence and gravitational pull are nonetheless fundamental to our understanding of the universe. For example, the presence of dark matter, estimated to be about 85 percent of the total mass of the universe, shapes the form and movement of galaxies, and it is invoked by researchers to explain what is known about the large-scale structure and expansion of the universe.

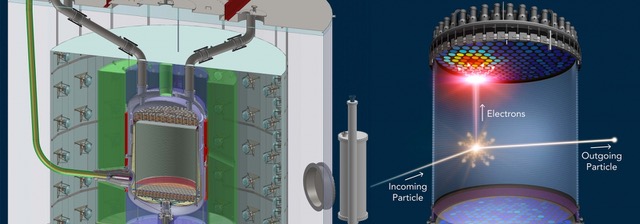

The heart of the LZ dark matter detector is comprised of two nested titanium tanks filled with ten tonnes of very pure liquid xenon and viewed by two arrays of photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) able to detect faint sources of light. The titanium tanks reside in a larger detector system to catch particles that might mimic a dark matter signal.

“I’m thrilled to see this complex detector ready to address the long-standing issue of what dark matter is made of,” said Berkeley Lab Physics Division Director Nathalie Palanque-Delabrouille. “The LZ team now has in hand the most ambitious instrument to do so!”

The design, manufacturing, and installation phases of the LZ detector were led by Berkeley Lab project director Gil Gilchriese in conjunction with an international team of 250 scientists and engineers from 35 institutions from the US, UK, Portugal, and South Korea. The LZ Operations Manager is Berkeley Lab’s Simon Fiorucci. Together, the collaboration is hoping to use the instrument to record the first direct evidence of dark matter, the so-called missing mass of the cosmos.

Henrique Araújo, from Imperial College London, leads the UK groups and previously the last phase of the UK-based ZEPLIN-III program. He worked very closely with the Berkeley team and other colleagues to integrate the international contributions. “We started out with two groups with different outlooks and ended up with a highly tuned orchestra working seamlessly together to deliver a great experiment,” Araújo said.

An underground detector

Tucked away about a mile underground at SURF in Lead, S.D., LZ is designed to capture dark matter in the form of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs). The experiment is underground to protect it from cosmic radiation at the surface that could drown out dark matter signals.

Particle collisions in the xenon produce visible scintillation or flashes of light, which are recorded by the PMTs, explained Aaron Manalaysay from Berkeley Lab who, as Physics Coordinator, led the collaboration’s efforts to produce these first physics results. “The collaboration worked well together to calibrate and to understand the detector response,” Manalaysay said. “Considering we just turned it on a few months ago and during COVID restrictions, it is impressive we have such significant results already.”

(Left) A schematic of the LZ detector. (Right) Illustration of LZ operation – particles interact in liquid xenon, releasing a flash of light and charge that are collected by photomultiplier tube arrays at top and bottom. Credit: Left schematic: LZ collaboration. Right image: LZ/SLAC

The collisions will also knock electrons off xenon atoms, sending them to drift to the top of the chamber under an applied electric field where they produce another flash permitting spatial event reconstruction. The characteristics of the scintillation help determine the types of particles interacting in the xenon.The South Dakota Science and Technology Authority, which manages SURF through a cooperative agreement with the US Department of Energy, secured 80 percent of the xenon in LZ. Funding came from the South Dakota Governor’s office, the South Dakota Community Foundation, the South Dakota State University Foundation, and the University of South Dakota Foundation.

Mike Headley, executive director of SURF Lab, said, “The entire SURF team congratulates the LZ Collaboration in reaching this major milestone. The LZ team has been a wonderful partner and we’re proud to host them at SURF.”

Fiorucci said the onsite team deserves special praise at this startup milestone, given that the detector was transported underground late in 2019, just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. He said with travel severely restricted, only a few LZ scientists could make the trip to help on site. The team in South Dakota took excellent care of LZ.

“I’d like to second the praise for the team at SURF and would also like to express gratitude to the large number of people who provided remote support throughout the construction, commissioning and operations of LZ, many of whom worked full time from their home institutions making sure the experiment would be a success and continue to do so now,” said Tomasz Biesiadzinski of SLAC, the LZ Detector Operations Manager.

“Lots of subsystems started to come together as we started taking data for detector commissioning, calibrations and science running. Turning on a new experiment is challenging, but we have a great LZ team that worked closely together to get us through the early stages of understanding our detector,” said David Woodward from Pennsylvania State University who coordinates the detector run planning.

Maria Elena Monzani of SLAC, the Deputy Operations Manager for Computing and Software, said “We had amazing scientists and software developers throughout the collaboration, who tirelessly supported data movement, data processing, and simulations, allowing for a flawless commissioning of the detector. The support of NERSC [National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center] was invaluable.”

With confirmation that LZ and its systems are operating successfully, Lesko said, it is time for full-scale observations to begin in hopes that a dark matter particle will collide with a xenon atom in the LZ detector very soon.

LZ is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science user facility. LZ is also supported by the Science & Technology Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology; and the Institute for Basic Science, Korea. Over 40 institutions of higher education and advanced research provided support to LZ. The LZ collaboration acknowledges the assistance of the Sanford Underground Research Facility.

###

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 14 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at https://www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter @Fermilab.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Editor’s note: The following feature story is being published jointly by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, and Symmetry, a publication of Fermilab and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

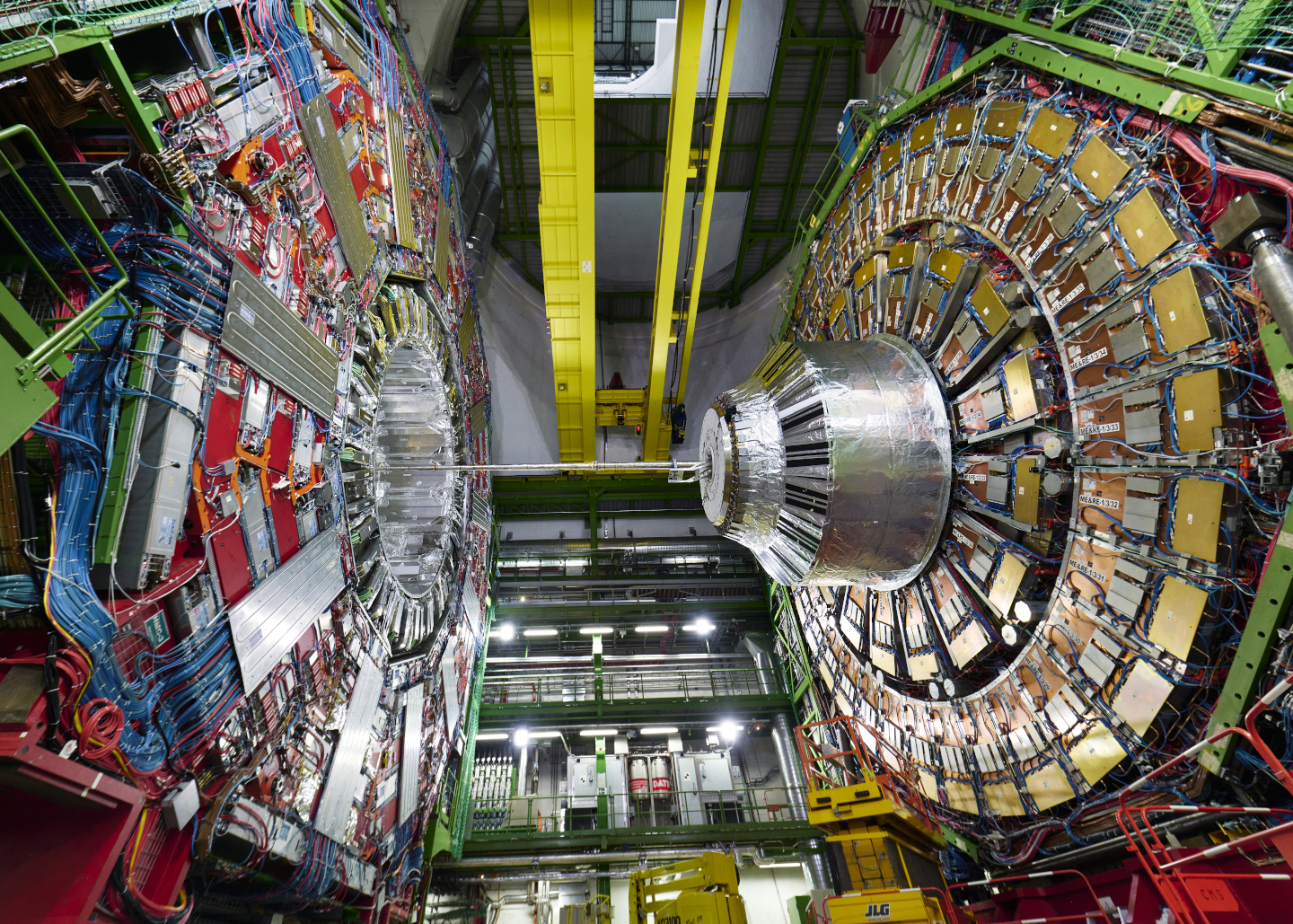

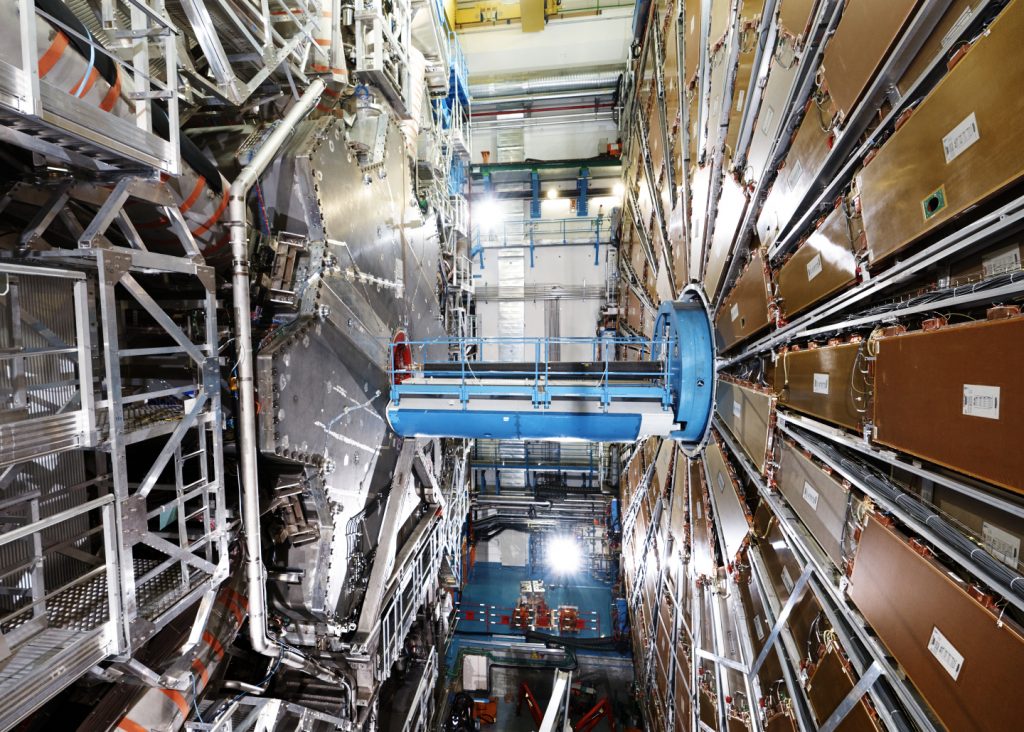

Particle physics changed forever on July 4, 2012. That was the day the two major physics experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, CMS and ATLAS, jointly announced the discovery of a particle that matched the properties of the Higgs boson—a particle theorized decades earlier. The discovery cemented the final piece in the Standard Model of particle physics.

In the decade since, physicists on CMS and ATLAS have studied the Higgs boson tenaciously, probing its properties and teasing out its secrets.

This week, on the 10-year anniversary of the Higgs discovery, CMS and ATLAS have released comprehensive new measurements of this particle in a special edition of the journal Nature. Both collaborations have measured properties of the Higgs boson more precisely than ever before, but neither has uncovered any surprises—yet.

“The particle that was discovered [in 2012] looks more and more like the Standard Model Higgs boson,” says Kétévi Assamagan, an ATLAS physicist at the US Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory who was convener for the experiment’s Higgs group from 2008-2010. “Nevertheless, there is room for new physics.”

“What’s really impressive is how well the experiments have measured these properties,” says Sally Dawson, a theorist at Brookhaven and co-author of the book The Higgs Hunter’s Guide. “We would have never guessed it … It’s truly phenomenal.”

“Now we know a whole lot about the Higgs, because particle physics predicted how the Higgs would be produced, how it would decay, the signatures that we would see. And it appears to be that it’s happening just the way it’s predicted.”

Liza Brost is an ATLAS physicist who has been studying the Higgs boson since its discovery—literally. (She started working at CERN on July 3, 2012.) “It’s really fun to have this new particle that we can analyze in detail and see what it is, how it behaves,” says Brost, who now works for Brookhaven.

Daniel Guerrero, a CMS researcher at DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, agrees: “After we discovered the Higgs boson, a completely new field of exploration opened for experiments at the LHC.”

In the last 10 years, the LHC completed its second run of data-taking, called Run 2. During this time, the collision energy was raised from 8 teraelectronvolts (TeV) to 13 TeV, increasing the rate of Higgs production and resulting in much more data for the experiments to collect and analyze.

For example, ATLAS estimates that about 9 million Higgs bosons were produced in the ATLAS detector during Run 2—30 times more than in 2012 (though they only analyze a fraction of that number).

“The Higgs boson has only gotten ‘bigger’ [in the last decade],” says Fermilab CMS researcher Nicholas Smith, speaking metaphorically (the Higgs boson mass remains approximately 125 GeV, now measured to a precision of 0.1%). “We’ve only gotten better and better at seeing it.”

Precision measurements

Higgs bosons are created by accelerating beams of protons around the LHC’s 17-mile-circumference circular tunnel at close to the speed of light and colliding them. Two beams travel in opposite directions and collide at four points along the ring, including at the CMS and ATLAS detectors. The collisions trigger the formation of new particles, which sometimes interact and turn into a Higgs boson.

Studying the combinations of particles that can create a Higgs boson—called production channels or modes—and the particles into which it decays—called decay modes—gives physicists a better understanding of the particle.

The new CMS and ATLAS results were obtained by combining several separate analyses of Higgs boson production modes and their corresponding decay modes.

“The combination is basically taking the division of labor [by separate analyses] and then recombining it into something that is interpretable as one physics result,” says Smith, who is a co-convener of the CMS Higgs combination group. “The more [decay modes] you can cover, the more stringent limits you can place on the way the Higgs production behaves, and vice versa: the more production modes you look at, the more you can place stringent constraints on how it decays.”

Some of the key measurements include how the Higgs interacts with other particles. These interactions, or couplings, are part of the mechanism by which the Higgs gives mass to other fundamental particles.

The ATLAS Collaboration measured the Higgs couplings to the top quark, bottom quark and tau lepton with uncertainties ranging from about 7% to 12%, as well as the couplings to the W and Z bosons with uncertainties of about 5%.

Many of the individual Higgs properties reported in the CMS paper were measured with accuracies better than 10% with a combined precision of almost 5% — a major improvement over the more than 20% combined precision in 2012.

All the new CMS and ATLAS measurements were consistent with predictions of the Standard Model within uncertainties. But that doesn’t mean there’s no new physics to be found, says Guerrero. “The effects of beyond-the-Standard-Model physics still can be hidden within those uncertainties, so that’s not a show-stopper,” he says. “Actually, we want to go further to see if, after we go to a higher precision, we can start to see deviations.”

Room for discovery

Indeed, there is plenty of room for new phenomena beyond the Standard Model, as some of the Higgs boson’s key properties remain to be measured by both CMS and ATLAS. These include some of its rare decay modes and the coupling of the Higgs boson to itself.

This Higgs boson self-coupling is a phenomenon intensely studied by CMS and ATLAS, both of which set constraints on it in their new papers. It’s also related to Higgs pair production, an extremely rare interaction in which two Higgs bosons, instead of just one, are created in a single production channel; CMS and ATLAS have not observed it yet but established new limits on the probability of this process taking place.

Eventually observing Higgs self-coupling and Higgs pair production will allow physicists to better understand a property called the Higgs potential. This property of the field generated by the Higgs “has connections to the matter-antimatter asymmetry in the early universe and electroweak symmetry breaking—all of these huge questions that we usually don’t even get close to touching on in our line of work,” says Brost.

Now, though, physicists are looking forward to the data to be collected during LHC Run 3, which began July 5 and will last close to four years. They all agree that the next steps for Higgs research require more data—and lots of it.

With more data, the experimental measurements can become even more precise, and that will push theorists to calculate their predictions more precisely as well, says Dawson. One day, if a more-precise prediction diverges from the experimental measurements of the Higgs boson, it could point to new physics.

“The discovery of the Higgs allowed us to have a bit of direction,” says Assamagan. “In the process as well, we have come up with better techniques for doing analyses [and] we’ve improved our understanding of the detectors. So, a lot of progress has been made. And I think we are certainly in a better position now to discover new physics if it is there.”

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at https://www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter @Fermilab.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://science.energy.gov.