Batavia, Illinois — Leon Lederman, a trailblazing researcher with a passion for science education who served as Fermilab’s director from 1979 to 1989 and won the Nobel Prize for discovery of the muon neutrino, died peacefully on Oct. 3 at a nursing home in Rexburg, Idaho. He was 96.

He is survived by his wife of 37 years, Ellen, and three children, Rena, Jesse and Rachel, from his first wife, Florence Gordon.

With a career that spanned more than 60 years, Lederman became one of the most important figures in the history of particle physics. He was responsible for several breakthrough discoveries, uncovering new particles that elevated our understanding of the fundamental universe. But perhaps his most critical achievements were his influence on the field and his efforts to improve science education.

“Leon Lederman provided the scientific vision that allowed Fermilab to remain on the cutting edge of technology for more than 40 years,” said Nigel Lockyer, the laboratory’s current director. “Leon’s leadership helped to shape the field of particle physics, designing, building and operating the Tevatron and positioning the laboratory to become a world leader in accelerator and neutrino science. Today, we continue to develop and build the next generation of particle accelerators and detectors and help to advance physics globally. Leon had an immeasurable impact on the evolution of our laboratory and our commitment to future generations of scientists, and his legacy will live on in our daily work and our outreach efforts.”

Through Lederman’s early award-winning work, he rose to prominence as a researcher and began to influence science policy. In the early 1960s, he proposed the idea for the National Accelerator Laboratory, which eventually became Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab). He worked with laboratory founder Robert R. Wilson to establish a community of users, credentialed individuals from around the world who could use the facilities and join experimental collaborations.

According to Fermilab scientist Alvin Tollestrup, who worked with Lederman for more than 40 years, Lederman’s success was in part due to his ability to bring people together and get them to work cohesively.

“One of his greatest skills was getting good people to work with him,” Tollestrup said. “He wasn’t selfish about his ideas. What he accomplished came about from his ability to put together a great team.”

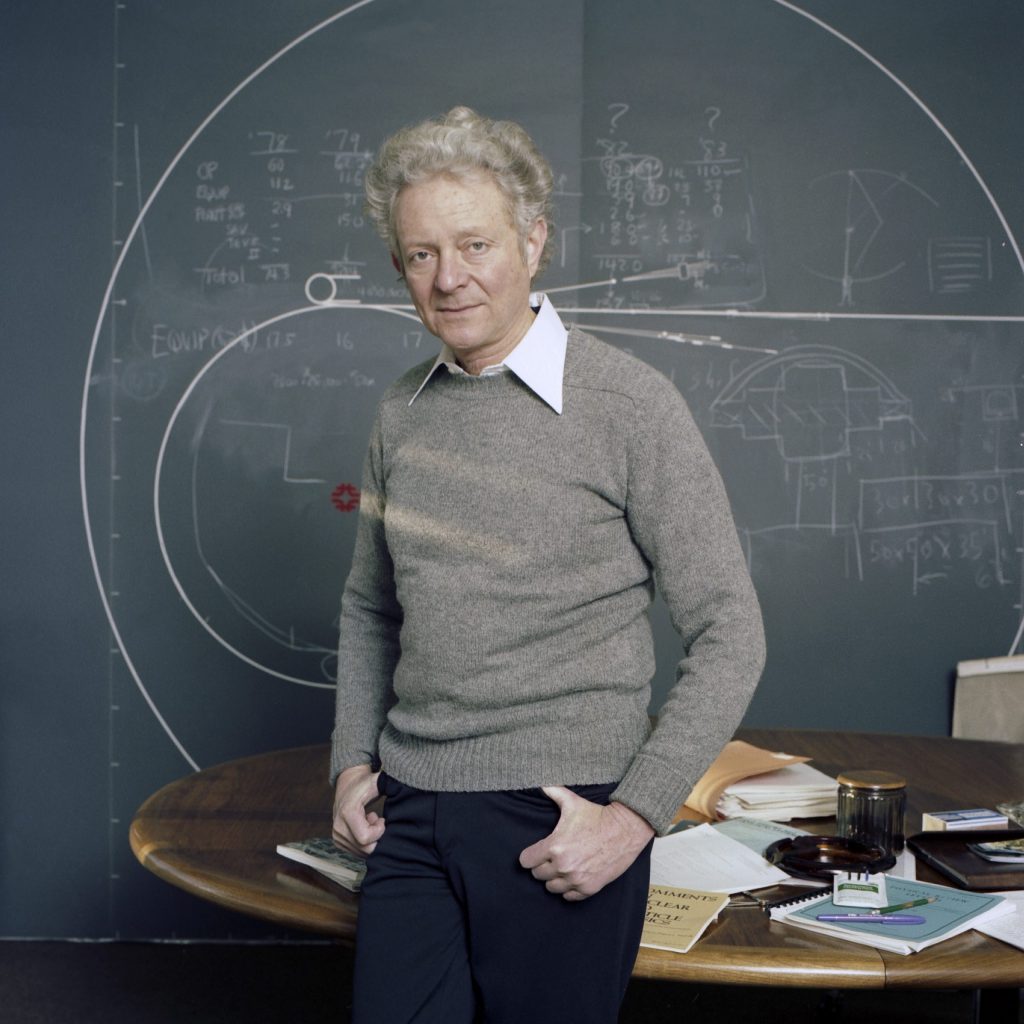

Lederman began his tenure as Fermilab director in 1978, at a time when both the laboratory staff and the greater particle physics community were deeply divided. As a charismatic leader and a respected researcher, Lederman unified the Fermilab staff and rallied the U.S. particle physics community around the idea of building a proton-antiproton collider. Originally called the energy doubler, the particle accelerator eventually became the Tevatron, the world’s highest-energy particle collider from 1983 until 2010.

“Leon gave U.S. and world physicists a step up, a unique facility, a very high-energy collider, and his successors keep working for these things,” said Director Emeritus John Peoples, who worked with Lederman for more than 40 years and served as Lederman’s deputy director from 1988 to 1989. “Leon made that happen. He set things in motion.”

In order to begin plans for a high-energy proton-antiproton collider, Lederman convinced the greater physics community, the Department of Energy, president Reagan’s science advisor and Congress.

“Leon had the ability to lead. He was unifying and convincing,” Peoples said. “He had the ability to listen to people carefully and could synthesize things well. He was very persuasive. In some sense, I was manipulated at every level.”

Lederman’s ability to convince others stemmed in part from his charm and his sense of humor, Peoples said.

“He seemed to have an enormous storehouse of jokes,” Peoples said. “He had a lighthearted personality, he could have been a stand-up comic at times.”

Lederman was born on July 15, 1922, to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents in New York City. His father, who operated a hand laundry, revered learning. Lederman graduated from the City College of New York with a degree in chemistry in 1943, although by that point, he had become friends with a group of physicists and became interested in the topic. He served three years with the United States Army in World War II and then returned to Columbia University in New York to pursue his Ph.D. in particle physics, which he received in 1951. During graduate school, Lederman joined the Columbia physics department in constructing a 385-MeV synchrocyclotron at Nevis Lab at Irvington-on-the Hudson, New York. He remained as part of that collaboration for 28 years and eventually serving as director of Nevis labs from 1961 to 1978.

In 1956, while working as part of a Columbia team at Brookhaven National Laboratory, Lederman discovered the long-lived neutral K meson. In 1962, Lederman, along with colleagues Jack Steinberger and Melvin Schwartz, produced a beam of neutrinos using a high-energy accelerator. They discovered that sometimes, instead of producing an electron, a muon is produced, showing the existence of a new type of neutrino, the muon neutrino. That discovery eventually earned them the 1988 Nobel Prize in physics.

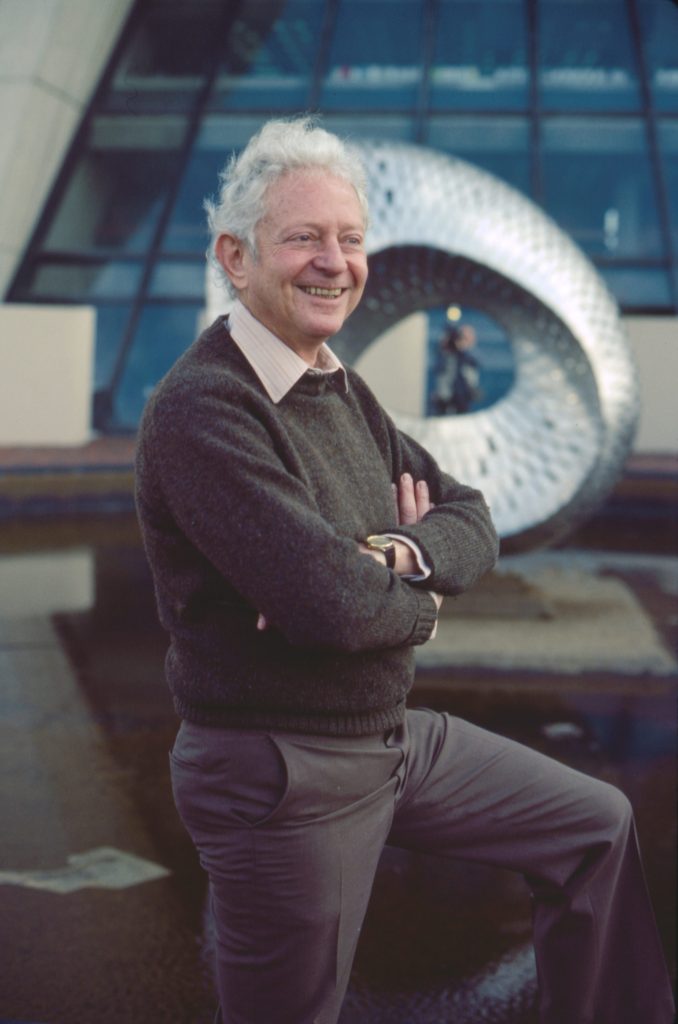

Leon Lederman stands outside Wilson Hall at Fermilab on the day he learned he was awarded the 1988 Nobel Prize.

The advancement of particle accelerators continued to spur discoveries. At Brookhaven in 1965, Lederman and his team found the first antinucleus in the form of antideuteron — an antiproton and an antineutron. In 1977, at Fermilab, Lederman led the team that discovered the bottom quark, at the time the first of a suspected new family of heavy particles.

“All of those experiments were important because they set the stage for learning that we have at least two generations of leptons and something else,” Tollestrup said.

Lederman served as director of Fermilab from 1978 to 1989. During his tenure as laboratory director, Lederman had a significant impact on laboratory culture. He was responsible for establishing new amenities that set Fermilab apart from other labs, such as the first daycare facility at a Department of Energy national laboratory and an art gallery that continues to host rotating exhibits.

He also had significant impact on the next generation of scientists. It was during his years at Columbia, an institution that required students to teach, that Lederman developed a passion for science education and outreach, which became a theme throughout his career. Between 1951 and 1978 he mentored 50 Ph.D. students. He liked to joke about their success, saying that not a single one was in jail.

As director of Fermilab, Lederman established the ongoing Saturday Morning Physics program, which has attracted students from around the Chicago areas for decades to learn more about particle physics from experts, originally from Lederman, and then a long list of leading scientists. The program has inspired generations of high school students.

Recognizing the need for more focused education in science and math, Lederman focused on creating learning spaces and opportunities for students. In the early 1980s, Lederman worked with members of the Illinois state government to start the Illinois Math and Science Academy, which was founded in 1985, and worked with officials to try to adjust the science curriculum in Chicago’s public schools so that students learned physics first, forming the foundation for their future scientific education. He founded and was chairman of the Teachers Academy for Mathematics and Science and was active in the professional development of primary school teachers in Chicago. He also helped to found the nonprofit Fermilab Friends for Science Education, a national leading organization in precollege science education.

In later years, Lederman continued his outreach efforts, often in memorable ways. In 2008, he set up shop on the corner of 34th Street and 8th Avenue in New York City and answered science questions from passersby.

During his career, Lederman received some of the highest national and international awards and honors given to scientists. These include the 1965 National Medal of Science, the 1972 Elliot Creeson Medal from the Franklin Institute, the Wolf Prize in 1982 and the Nobel Prize in 1988. He received the Enrico Fermi Award in 1992 for his career contributions to science, technology and medicine related to nuclear energy and the science and technology of energy, and was given the Vannevar Bush Award in 2012 for exceptional lifelong leaders in science and technology.

In addition to his appointments at Columbia, Nevis and Fermilab, Lederman also served as the Pritzker professor of science at Illinois Institute of Technology and chairman of the State of Illinois Governor’s Science Advisory Committee. He also served on the Board of the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, the Secretary of Energy Advisory Board and others.

When Lederman stepped down as Fermilab’s director in 1989 and Peoples took the role, Lederman shared some sage advice. A desk nameplate, which sits on Peoples’s desk more than 25 years later, reads “I’m listening.”

Editor’s note: This article has been corrected. Lederman began his term as Fermilab director in 1979, not 1978 as was originally published.