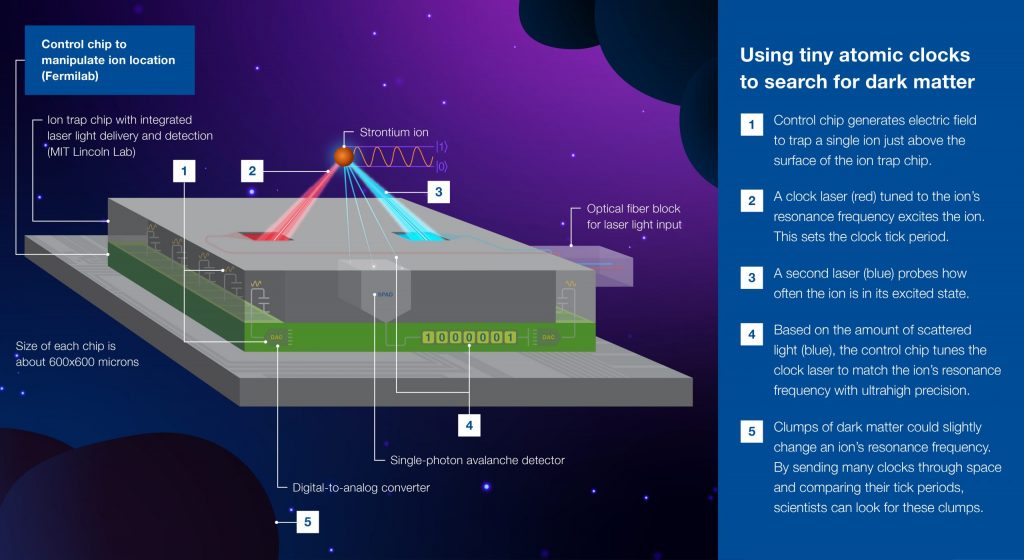

In the search for dark matter — the mysterious, invisible substance that makes up more than 80% of matter in our universe — scientists and engineers are turning to a new ultra-sensitive tool: the optical atomic clock.

These clocks, which measure time by using an ultra-stable laser to monitor the resonant frequency of atoms, are now precise enough that if they ran for the age of the universe, they would lose less than one second. That stability also enables these devices to act as extremely sensitive quantum sensors that could be deployed into space to search for dark matter.

The challenge: The equipment required to operate such ultra-precise clocks — including lasers, electronics and coolers — can fill a large table or even a room. It would make launching them into space very expensive if not impossible.

Scientists working on a joint U.S. Department of Energy and Department of Defense project aim to miniaturize these elements to the size of a shoebox. After more than two years of work, the researchers — from the DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory — have reported initial promising results.

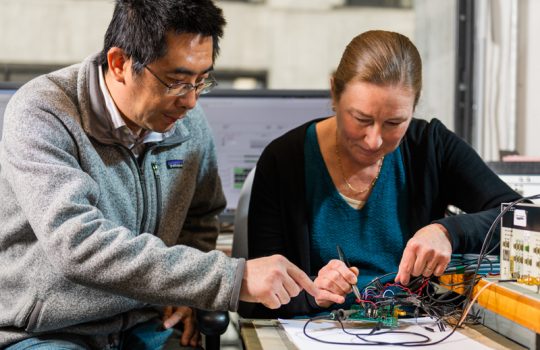

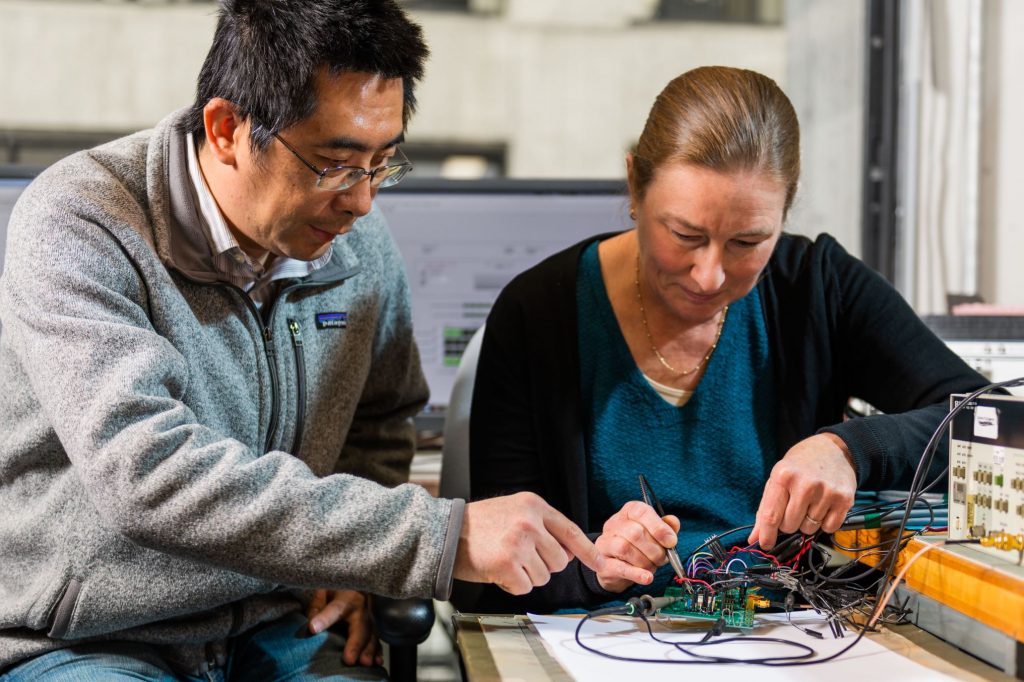

Fermilab researchers Hongzhi Sun and Pamela Klabbers test the chip at the test stand. Photo: Ryan Postel, Fermilab

Fermilab researchers designed and developed the compact electronics needed to control the voltages within the device, while MIT LL researchers are developing the tiny ion traps and corresponding photonics needed to build the clock. The chip designed by the Fermilab team is currently under testing at MIT LL.

“This is the first step toward a high-accuracy, small footprint atomic clock,” said Fermilab Microelectronics Division Director Farah Fahim, who leads the project for the lab.

A new way to detect dark matter

MIT LL’s optical atomic clock uses an ion trap as a sensor — in this case, a Strontium ion that is confined by an electrical field. A laser acts as the clock’s oscillator, measuring the oscillation frequency of the ion’s transition between two quantized energy levels.

This sort of compact atomic clock could be ideal for deployment to space to search for ultralight dark matter, which is theorized to cause oscillations in the masses of electrons. If several atomic clocks traveled through a clump of dark matter in space, the dark matter could increase or decrease the photon energy measured by each clock, changing how it “ticks.” The clocks would desynchronize as the dark matter passes and resynchronize thereafter.

Researchers conducted these experiments with GPS satellites, which each contain multiple atomic clocks based on a different technology. But they found no evidence for dark matter in these experiments. Perhaps, the researchers considered, dark matter could be detected with a more sensitive clock.

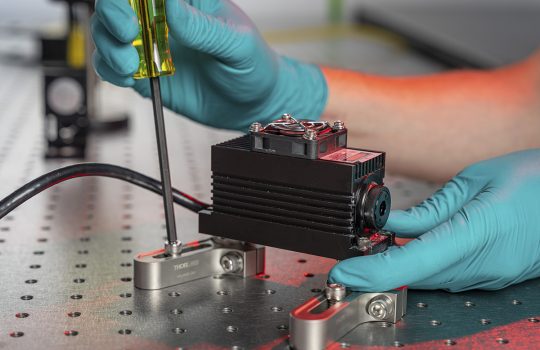

Funded by the DOD, MIT LL researchers have miniaturized the trapped-ion atomic clock, integrating laser delivery and detection all onto one chip. But to complete the system, MIT LL researchers needed more than just miniaturized atomic and photonic components. They needed help designing a miniature electronic control system. That’s where Fermilab came in; DOE’s high-energy physics QuantISED program funded the electronics development and integration.

“We have more than 30 years of experience developing compact electronics for collider physics, and we have developed chips for extreme environments,” Fahim said. “That’s not unlike the electronics needed for controlling atoms and reading out their state.”

“It’s a project that really leverages the unique capabilities of different government laboratories,” said Robert McConnell, staff scientist at MIT LL who led development of the photonic ion trap chip for the project.

Integrating compact electronics with the ion trap

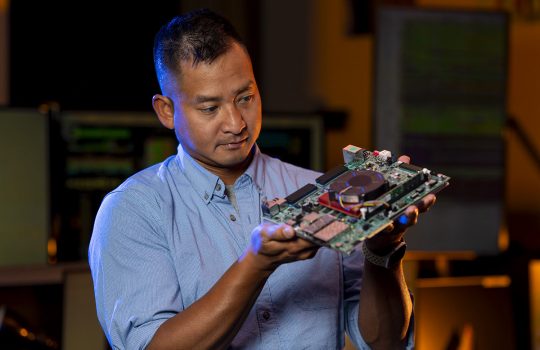

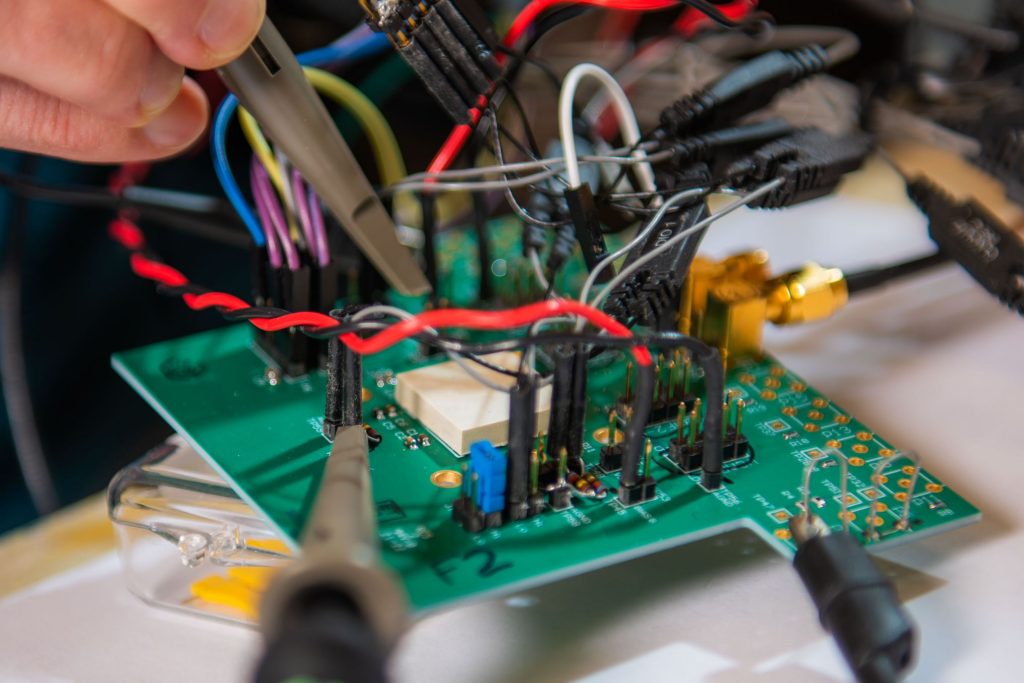

The difficulty lies in creating a small chip that can control the high voltages needed for the system — at least 20 volts — while both retaining high speed and utilizing low power. Working with a semiconductor manufacturer, the Fermilab team recently created a chip that could control up to nine volts. “It also has low voltage noise, so it won’t perturb the quantum state of the ion,” said Hongzhi Sun, the lead chip designer on the project.

Ready for testing: The chip’s custom test board is connected the test equipment. The chip is wire-bonded to the board and protected by the square white plastic cap. Photo: Ryan Postel, Fermilab

MIT LL researchers now look to integrate the chip with the ion trap through a technique that allows them to stack the two chips on top of each other and connect them through vias, or electrical connections between layers. Fermilab researchers will then continue to hone the electronics design to increase the voltage up to 20 volts. The goal is to create a compact atomic clock with frequency uncertainty of 10-18.

Other applications

“This collaboration allows us the benefits of both worlds,” said McConnell. “By having Fermilab design circuits and integrating them with our ion traps, we can create well-controllable quantum sensors.”

The clocks could be used beyond high-energy physics research, including in space defense or even as extremely sensitive sensors that could predict tsunamis or earthquakes. These ion traps could also form the basis for future quantum computers.

“There is a great disparity in the application goals for DOD and DOE but an equally compelling synergy in the underlying technology development; we simply need to find ways to work together,” Fahim said.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.