Fermilab editor’s note: This press release was originally posted by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory contributed key elements to the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), including the online databases used for data acquisition and the software that ensures that each of the 5,000 robotic positioners are precisely pointing to their celestial targets to within a tenth of the width of a human hair. Fermilab also contributed the corrector barrel, hexapod and cage. The corrector barrel holds DESI’s six large lenses in precise alignment. The hexapod, designed and built with partners in Italy, focuses the DESI images by moving the barrel-lens system. Both the barrel and hexapod are housed in the cage, which provides the attachment to the telescope structure. In addition, Fermilab carried out the testing and packaging of DESI’s charge-coupled devices, or CCDs. The CCDs convert the light passing through the lenses from distant galaxies into digital information that can then be analyzed by the collaboration.

“These results are very exciting and show the immense power of the DESI data,” said Liz Buckley-Geer, Fermilab scientist and one of the DESI lead observers responsible for the collection of the data. “I am looking forward to helping to acquire even more data as we continue the survey.”

Key takeaways:

- A complex analysis of DESI’s first year of data provides one of the most stringent tests yet of general relativity and how gravity behaves at cosmic scales

- Looking at galaxies and how they cluster across time reveals the growth of cosmic structure, which lets DESI test theories of modified gravity – an alternative explanation for our universe’s accelerating expansion

- DESI researchers found that the way galaxies cluster is consistent with our standard model of gravity and the predictions from Einstein’s theory of general relativity

Gravity has shaped our cosmos. Its attractive influence turned tiny differences in the amount of matter present in the early universe into the sprawling strands of galaxies we see today. A new study using data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) has traced how this cosmic structure grew over the past 11 billion years, providing the most precise test to date of gravity at very large scales.

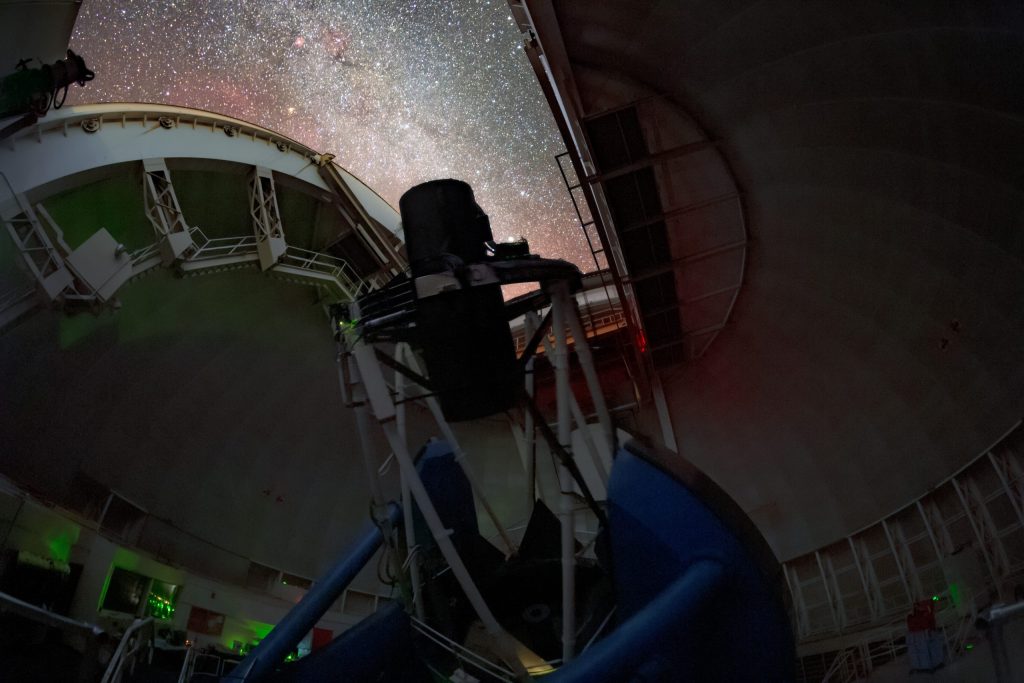

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument observes the sky from the Mayall Telescope, shown here during the 2023 Geminid meteor shower. Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Sparks

DESI is an international collaboration of more than 900 researchers from over 70 institutions around the world and is managed by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab). In their new study, DESI researchers found that gravity behaves as predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The result validates our leading model of the universe and limits possible theories of modified gravity, which have been proposed as alternative ways to explain unexpected observations – including the accelerating expansion of our universe that is typically attributed to dark energy.

“General relativity has been very well tested at the scale of solar systems, but we also needed to test that our assumption works at much larger scales,” said Pauline Zarrouk, a cosmologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) working at the Laboratory of Nuclear and High-Energy Physics (LPNHE), who co-led the new analysis. “Studying the rate at which galaxies formed lets us directly test our theories and, so far, we’re lining up with what general relativity predicts at cosmological scales.”

The study also provided new upper limits on the mass of neutrinos, the only fundamental particles whose masses have not yet been precisely measured. Previous neutrino experiments found that the sum of the masses of the three types of neutrinos should be at least 0.059 eV/c2. (For comparison, an electron has a mass of about 511,000 eV/c2.) DESI’s results indicate that the sum should be less than 0.071 eV/c2, leaving a narrow window for neutrino masses.

The DESI collaboration shared their results in several papers posted to the online repository arXiv today. The complex analysis used nearly 6 million galaxies and quasars and lets researchers see up to 11 billion years into the past. With just one year of data, DESI has made the most precise overall measurement of the growth of structure, surpassing previous efforts that took decades to make.

Today’s results provide an extended analysis of DESI’s first year of data, which in April made the largest 3D map of our universe to date and revealed hints that dark energy might be evolving over time. The April results looked at a particular feature of how galaxies cluster known as baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO). The new analysis, called a “full-shape analysis,” broadens the scope to extract more information from the data, measuring how galaxies and matter are distributed on different scales throughout space. The study required months of additional work and cross-checks. Like the previous study, it used a technique to hide the result from the scientists until the end, mitigating any unconscious bias.

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument imaging the night sky in 2022. Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/T. Slovinský

“Both our BAO results and the full-shape analysis are spectacular,” said Dragan Huterer, professor at the University of Michigan and co-lead of DESI’s group interpreting the cosmological data. “This is the first time that DESI has looked at the growth of cosmic structure. We’re showing a tremendous new ability to probe modified gravity and improve constraints on models of dark energy. And it’s only the tip of the iceberg.”

DESI is a state-of-the-art instrument that can capture light from 5,000 galaxies simultaneously. It was constructed and is operated with funding from the DOE Office of Science. DESI sits atop the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Nicholas U. Mayall 4-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory (a program of NSF’s NOIRLab). The experiment is now in its fourth of five years surveying the sky and plans to collect roughly 40 million galaxies and quasars by the time the project ends.

The collaboration is currently analyzing the first three years of collected data and expects to present updated measurements of dark energy and the expansion history of our universe in spring 2025. DESI’s expanded results released today are consistent with the experiment’s earlier preference for an evolving dark energy, adding to the anticipation of the upcoming analysis.

“Dark matter makes up about a quarter of the universe, and dark energy makes up another 70 percent, and we don’t really know what either one is,” said Mark Maus, a PhD student at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley who worked on theory and validation modeling pipelines for the new analysis. “The idea that we can take pictures of the universe and tackle these big, fundamental questions is mind-blowing.”

DESI is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science user facility. Additional support for DESI is provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation; the Science and Technology Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; the Heising-Simons Foundation; the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA); the National Council of Humanities, Sciences, and Technologies of Mexico; the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain; and by the DESI member institutions.

The DESI collaboration is honored to be permitted to conduct scientific research on I’oligam Du’ag (Kitt Peak), a mountain with particular significance to the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) is committed to delivering solutions for humankind through research in clean energy, a healthy planet, and discovery science. Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest problems are best addressed by teams, Berkeley Lab and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Researchers from around the world rely on the lab’s world-class scientific facilities for their own pioneering research. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.