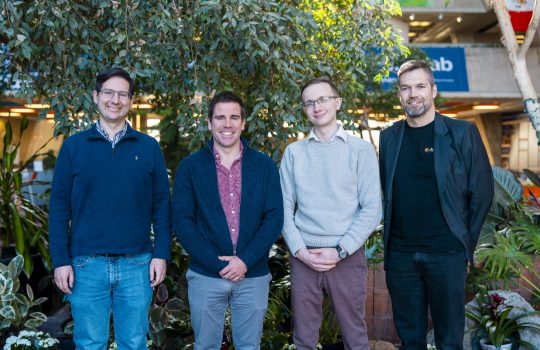

Consul General of Brazil Paulo Camargo (eighth from left) recently visited Fermilab, as did Janaina Solomos (fourth from left), also from the Brazilian consulate. Two directors of Brazilian national labs also visited Fermilab: Brazilian Center for Physics Research Director Ronald Shellard (11th from left) and National Observatory Director Joao dos Anjos (13th from left). Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer is 6th from the left. Brazilian scientists at Fermilab include Marcelle Soares-Santos (second from left), Fernanda Garcia (12th from left) and Carlos Escobar (sixth from right). Scientists at Brazilian institutions include Mateus Carneiro of the Brazilian Center for Physics Research (3rd from left) and Ernesto Kemp of the State University of Campinas (fourth from right). Photo: Reidar Hahn

“Wish you were here” wasn’t written on the postcard Carlos Escobar received in 1981, but it was the sentiment. A friend from Mexico, writing from Brookhaven National Laboratory, had switched from theoretical to experimental physics and was encouraging his Brazilian colleague to do the same. Within a few years Escobar would follow his friend’s advice and be among the first Brazilian physicists to conduct research at Fermilab.

Other Brazilian researchers followed his footsteps along the same inroads he helped lay. The Brazilian user community at Fermilab now consists of nearly 80 researchers from 15 institutions working across 13 different projects and experiments.

There was a vision, recalls Escobar, pervasive throughout Latin America when he got that note that their accomplished, theoretical high-energy physics community needed to begin running experiments of their own. That feeling led Escobar to help organize the Pan American Symposium on Elementary Particles and Technology in 1983, dedicated to showcasing HEP experiments around the globe. Directors of Fermilab, CERN, DESY and other influential labs were in attendance, and at the close of the conference, Fermilab Director Emeritus Leon Lederman bluntly said that since Brazilian institutions were not ready to pay for their researchers to come to Fermilab, he would.

Thus, Escobar, then based at the University of São Paulo, along with Alberto Santoro, João dos Anjos and Moacyr Souza, all from the Brazilian Center for Research in Physics in Rio de Janeiro, formed the first collaboration between Fermilab and South American institutions. The team worked on a fixed-target experiment, known as E691, for two years before bringing their learnings back to their home institutions.

“Of course, that was the whole purpose of us coming here,” said Escobar, now a guest scientist in the Fermilab Neutrino Division. “To return to Brazil and form our groups (Rio and São Paulo) working on experimental high-energy physics.”

So, when Marcelle Soares-Santos came to Fermilab as a graduate student in 2008, she inherited some dividends of Escobar’s and others’ work, notably an opportunity to work on a precursor of the Dark Energy Survey. She also benefited from some perks of a well-established scientific relationship, including a Brazil House in the Fermilab Village for students and a Brazilian community to help her transition to lab life.

Soares-Santos notes that as the scientific community in Brazil has blossomed, their contingent at Fermilab has concordantly grown and diversified into new projects. Currently, the largest contingent of Brazilian researchers collaborating with Fermilab work on DES, though most do so remotely. The largest groups of on-site Brazilians conduct research in the Neutrino Division or CMS at Fermilab.

Soares-Santos is now a permanent employee of the lab and says most of the researchers she meets follow the path the four Brazilians laid out: They stay for a relatively short term and leave to build on the science back home. She believes this benefits the researchers and the scientific community.

“It’s noticeable how much people grow,” Soares-Santos said. “And that, I think, has an impact back home on the level of science we’re doing today and bodes well for the level of science we hope to achieve.”