The U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science has awarded funding to Fermilab to use machine learning to improve the operational efficiency of Fermilab’s particle accelerators.

These machine learning algorithms, developed for the lab’s accelerator complex, will enable the laboratory to save energy, provide accelerator operators with better guidance on maintenance and system performance, and better inform the research timelines of scientists who use the accelerators.

Engineers and scientists at Fermilab, home to the nation’s largest particle accelerator complex, are designing the programs to work at a systemwide scale, tracking all of the data resulting from the operation of the complex’s nine accelerators. The pilot system will be used on only a few accelerators, with the plan to extend the program tools to the entire accelerator chain.

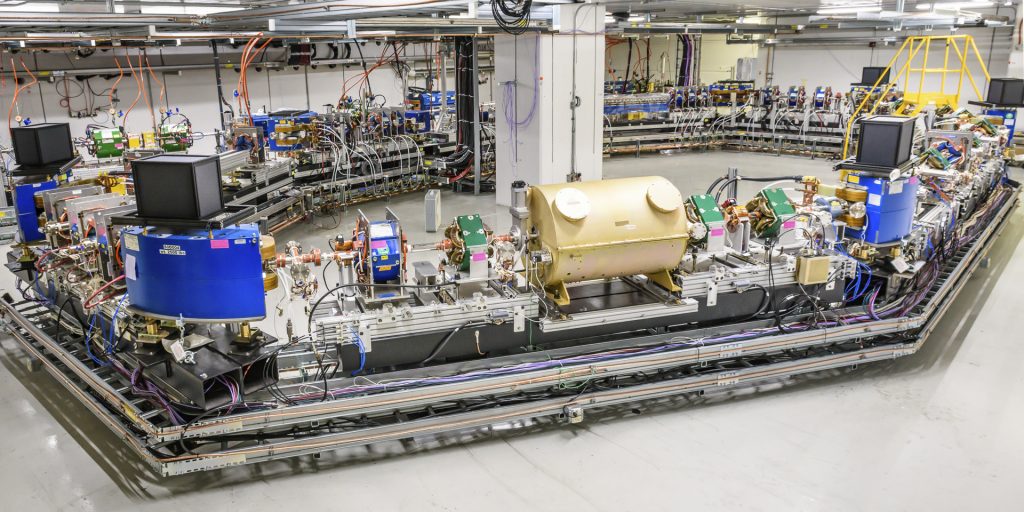

Engineers and scientists at Fermilab are designing machine learning programs for the lab’s accelerator complex. These algorithms will enable the laboratory to save energy, give accelerator operators better guidance on maintenance and system performance, and better inform the research timelines of scientists who use the accelerators. The pilot system will used on the Main Injector and Recycler, pictured here. It will eventually be extended to the entire accelerator chain. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

Fermilab engineer Bill Pellico and Fermilab accelerator scientist Kiyomi Seiya are leading a talented team of engineers, software experts and scientists in tackling the deployment and integration of framework that uses machine learning on two distinct fronts.

Untangling complex data

Creating a machine learning program for a single particle accelerator is difficult, says Fermilab engineer Bill Pellico, and Fermilab is home to nine. The work requires that operators track all the individual accelerator subsystems at once.

“Manually keeping track of every subsystem at the level required for optimum performance is impossible,” Pellico said. “There’s too much information coming from all these different systems. To monitor the hundreds of thousands of devices we have and make some sort of correlation between them requires a machine learning program.”

The diagnostic signals pinging from individual subsystems form a vast informational web, and the data appear on screens that cover the walls of Fermilab’s Main Control Room, command central for the accelerator complex.

Particle accelerator operators track all the individual accelerator subsystems at once. The diagnostic signals pinging from individual subsystems form a vast informational web, and the data appear on screens that cover the walls of Fermilab’s Main Control Room, command central for the accelerator complex, pictured here. A machine learning program will not only track signals, but also quickly determine what specific system requires an operator’s attention. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

The data — multicolored lines, graphs and maps — can be overwhelming. On one screen an operator may see data requests from scientists who use the accelerator facility for their experiments. Another screen might show signals that a magnet controlling the particle beam in a particular accelerator needs maintenance.

Right now, operators must perform their own kind of triage – identifying and prioritizing the most important signals coming in – ranging from fulfilling a researcher request to identifying a problem-causing component. A machine learning program, on the other hand, will be capable not only of tracking signals, but also of quickly determining what specific system requires attention from an operator.

“Different accelerator systems perform different functions that we want to track all on one system, ideally,” Pellico said. “A system that can learn on its own would untangle the web and give operators information they can use to catch failures before they occur.”

In principle, the machine learning techniques, when employed on such a large amount of data, would be able to pick up on the minute, unusual changes in a system that would normally get lost in the wave of signals accelerator operators see from day to day. This fine-tuned monitoring would, for example, alert operators to needed maintenance before a system showed outward signs of failure.

Say the program brought to an operator’s attention an unusual trend or anomaly in a magnet’s field strength, a possible sign of a weakening magnet. The advanced alert would enable the operator to address it before it rippled into a larger problem for the particle beam or the lab’s experiments. These efforts could also help lengthen the life of the hardware in the accelerators.

Improving beam quality and increasing machine uptime

While the overarching machine learning framework will process countless pieces of information flowing through Fermilab’s accelerators, a separate program will keep track of (and keep up with) information coming from the particle beam itself.

Any program tasked with monitoring a speed-of-light particle beam in real time will need to be extremely responsive. Seiya’s team will code machine learning programs onto fast computer chips to measure and respond to beam data within milliseconds.

Currently, accelerator operators monitor the overall operation and judge whether the beam needs to be adjusted to meet the requirements of a specific experiment, while computer systems help keep the beam stable locally. On the other hand, a machine learning program will be able to monitor both global and local aspects of the operation, pick up on critical beam information in real time, leading to faster improvements to beam quality and reduced beam loss — the inevitable loss of beam to the beam pipe walls.

“Information from the accelerator chain will pass through this one system,” Seiya said, Fermilab scientist leading the machine learning program for beam quality. “The machine learning model will then be able to figure out the best action for each.”

That best action depends on what aspect of the beam needs to be adjusted in a given moment. For example, monitors along the particle beamline will send signals to the machine-learning-based program, which will be able to determine whether the particles need an extra kick to ensure they’re traveling in the optimal position in the beam pipe. If something unusual occurs in the accelerator, the program can decide whether the beam has to be stopped or not by scanning the patterns of the monitors.

A tool for everyone

And while every accelerator has its particular needs, the accelerator-beam machine learning program implemented at Fermilab could be adapted for any particle accelerator, providing an example for operators at particle accelerators beyond Fermilab.

“We’re ultimately creating a tool set for everyone to use,” Seiya said. “These techniques will bring new and unique capabilities to accelerator facilities everywhere. The methods we develop could also be implemented at other accelerator complexes with minimal tweaks.”

This tool set will also save energy for the laboratory. Pellico estimates that 7% of an accelerator’s energy goes unused due to a combination of suboptimal operation, unscheduled maintenance and unnecessary equipment usage. This isn’t surprising considering the number of systems required to run an accelerator. Improvements in energy conservation make for greener accelerator operation, he said, and machine learning is how the lab will get there.

“The funding from DOE takes us a step closer to that goal,” he said.

The capabilities of this real-time tuning will be demonstrated on the beamline for Fermilab’s Mu2e experiment and in the Main Injector, with the eventual goal of incorporating the program into all Fermilab experiment beamlines. That includes the beam generated by the upcoming PIP-II accelerator, which will become the heart of the Fermilab complex when it comes online in the late 2020s. PIP-II will power particle beams for the international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, hosted by Fermilab, as well as provide for the long-term future of the Fermilab research program.

Both of the lab’s new machine learning applications, working in tandem, will benefit accelerator operation and the laboratory’s particle physics experiments. By processing patterns and signals from large amounts of data, machine learning gives scientists the tools they need to produce the best research possible.

The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Before researchers can smash together beams of particles to study high-energy particle interactions, they need to create those beams in particle accelerators. And the tighter the particles are packed in the beams, the better scientists’ chances of spotting rare physics phenomena.

Making a particle beam denser or brighter is akin to sticking an inflated balloon in the freezer. Just as reducing the random motion of the gas molecules inside the balloon causes the balloon to shrink, reducing the random motion of the particles in a beam makes the beam denser. But physicists do not have freezers for particles moving near the speed of light — so they devise other clever ways to cool down the beam.

An experiment underway at Fermilab’s Integrable Optics Test Accelerator seeks to be the first to demonstrate optical stochastic cooling, a new beam cooling technology that has the potential to dramatically speed up the cooling process. If successful, the technique would enable future experiments to generate brighter beams of charged particles and study previously inaccessible physics.

Fermilab’s optical stochastic cooling experiment is now underway at the 40-meter-circumference Integrable Optics Test Accelerator, a versatile particle storage ring designed to pursue innovations in accelerator science. Photo: Giulio Stancari, Fermilab

“There is this range of energies — about 10 to 1,000 GeV — where there currently exists no technology for cooling protons, and that’s where optical stochastic cooling could be applied at the moment,” said Fermilab scientist Alexander Valishev, the leader of the team that designed and constructed IOTA. “But if we develop it, then I’m sure there will be other applications.”

In January, IOTA’s OSC experiment started taking data. IOTA is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

OSC operates on the same principle as conventional stochastic cooling, a technology developed by Simon van der Meer and harnessed by Carlo Rubbia for the 1983 discovery of the W and Z bosons. Van der Meer and Rubbia won the 1984 Nobel Prize in physics for their work, which has since found use in many particle accelerators.

Stochastic cooling provides a way to measure how the particles in a beam move away from the desired trajectory and apply corrections to nudge them closer together, thus making the beam denser. The technique hinges on the interplay between charged particles and the electromagnetic radiation they emit.

As charged particles such as electrons or protons move in a curved path, they radiate energy in the form of light, which a pickup in the accelerator detects. Each light signal contains information about the average position and velocity of a “bunch” of millions or billions of particles.

Then an electromagnet device called a kicker applies this same signal back onto the bunch to correct any stray motion, like a soccer player kicking a ball to keep it in bounds. Each kick brings the average particle position and velocity closer to the desired value, but individual particles can still drift away. To correct the motion of individual particles and create a dense beam, the process must be repeated many thousands of times as the beam circulates in the accelerator.

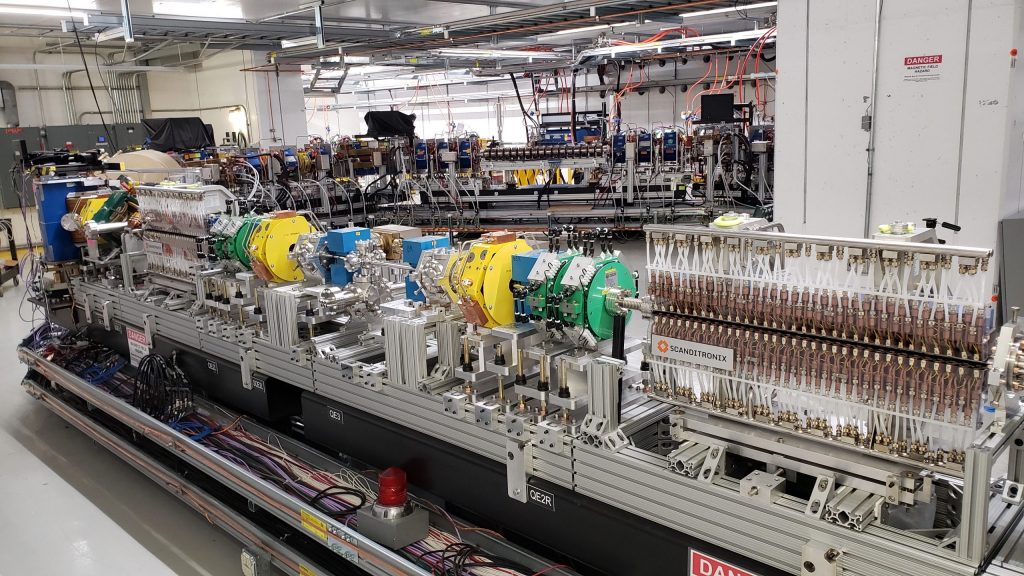

The two components with Scanditronix logos pictured here are the heart of IOTA’s optical stochastic cooling experiment. The pickup (left) measures the spread of the particle beam, and then the kicker (right) corrects the stray motion of the particles. Photo: Jonathan Jarvis, Fermilab

Traditional stochastic cooling uses electromagnetic signals in the microwave range, with centimeter-long wavelengths. OSC uses visible and infrared light, with wavelengths around a micron — a millionth of a meter.

“The scale is set by the wavelength,” Valishev said. “The shorter wavelengths mean we can read the beam information with higher resolution and better pinpoint corrections.”

The higher resolution allows OSC to provide more precise kicks to smaller groups of particles. Smaller groups of particles require fewer kicks in order to cool, just as a tiny balloon cools faster than a large one when put in the freezer. Each particle gets kicked once per lap around the accelerator. Since fewer kicks are required, the entire beam cools after fewer laps.

In principle, OSC could speed up beam cooling by a factor of 10,000 compared to conventional stochastic cooling. The first demonstration experiment at IOTA, which is using a medium-energy electron beam, has a more modest goal. As the beam circulates in the accelerator and radiates light, it loses energy, cooling on its own in about 1 second; IOTA seeks a tenfold decrease in that cooling time.

Proposals for OSC piqued the interest of the accelerator community as early as the 1990s, but so far a successful implementation has eluded researchers. Harnessing shorter wavelengths of light raises a host of technical challenges.

“The relative positions of all the relevant elements need to be controlled at the level of a quarter of a wavelength or better,” Valishev said. “In addition to that, you have to read the wave packet from the beam, and then you have to transport it, amplify it, and then apply it back onto the same beam. Again, everything must be done with this extreme precision.”

IOTA proved the perfect accelerator for the job. The centerpiece of the Fermilab Accelerator Science and Technology facility, IOTA has a flexible design that allows researchers to tailor the components in the beamline as they push the frontiers of accelerator science.

IOTA’s OSC experiment is beginning with electrons because these lightweight particles can easily and cheaply be accelerated to the speeds at which they radiate visible and infrared light. In the future, scientists hope to apply the technique to protons. Due to their larger mass, protons must reach higher energies to radiate the desired light, making them more difficult to handle.

At first, IOTA will study passive cooling, in which the light emitted by the electron beam will not be amplified before being shined back on the beam. After that simplified approach succeeds, the team will add optical amplifiers to strengthen the light that provides the corrective kicks.

In addition to providing a new cooling technology for high-energy particle colliders, OSC could enhance the study of fundamental electrodynamics and interactions between electrons and photons.

“Optical stochastic cooling is a blend of various areas of modern experimental physics, from accelerators and beams to light optics, all merged in one package,” Valishev said. “That makes it very challenging and also very stimulating to work on.”

The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.