The U.S. Large Hadron Collider Accelerator Upgrade Project is the Fermilab-led collaboration of U.S. laboratories that, in partnership with CERN and a dozen other countries, is working to upgrade the Large Hadron Collider. LHC AUP began just over two years ago and, on Feb. 11, it received key approvals, allowing the project to transition into its next steps.

U.S. Department of Energy projects undergo a series of key reviews and approvals, referred to as “Critical Decisions” that every project must receive. Earlier this month, the AUP earned approval for both Critical Decisions 2 and 3b from DOE. CD-2 approves the performance baseline — the scope, cost and schedule — for the AUP. In order to stay on that schedule, CD-3b allows the project to receive the funds and approval necessary to purchase base materials and produce final design models of two technologies by the end of 2019.

The LHC, a 17-mile-circumference particle accelerator on the French-Swiss border, smashes together two opposing beams of protons to produce other particles. Researchers use the particle data to understand how the universe operates at the subatomic scale.

In its current configuration, on average, an astonishing 1 billion collisions occur every second at the LHC. The new technologies developed for the LHC will boost that number by a factor of 10. This increase in luminosity — the number of proton-proton interactions per second — means that significantly more data will be available to experiments at the LHC. It’s also the reason behind the collider’s new name, the High-Luminosity LHC.

“The need to go beyond the already excellent performance of the LHC is at the basis of the scientific method,” said Giorgio Apollinari, Fermilab scientist and HL-LHC AUP project manager. “The endorsement and support received for this U.S. contribution to the HL-LHC will allow our scientists to remain at the forefront of research at the energy frontier.”

U.S. physicists and engineers helped research and develop two technologies to make this upgrade possible. The first upgrade is to the magnets that focus the particles. The new magnets rely on niobium-tin conductors and can exert a stronger force on the particles than their predecessors. By increasing the force, the particles in each beam are driven closer together, enabling more proton-proton interactions at the collision points.

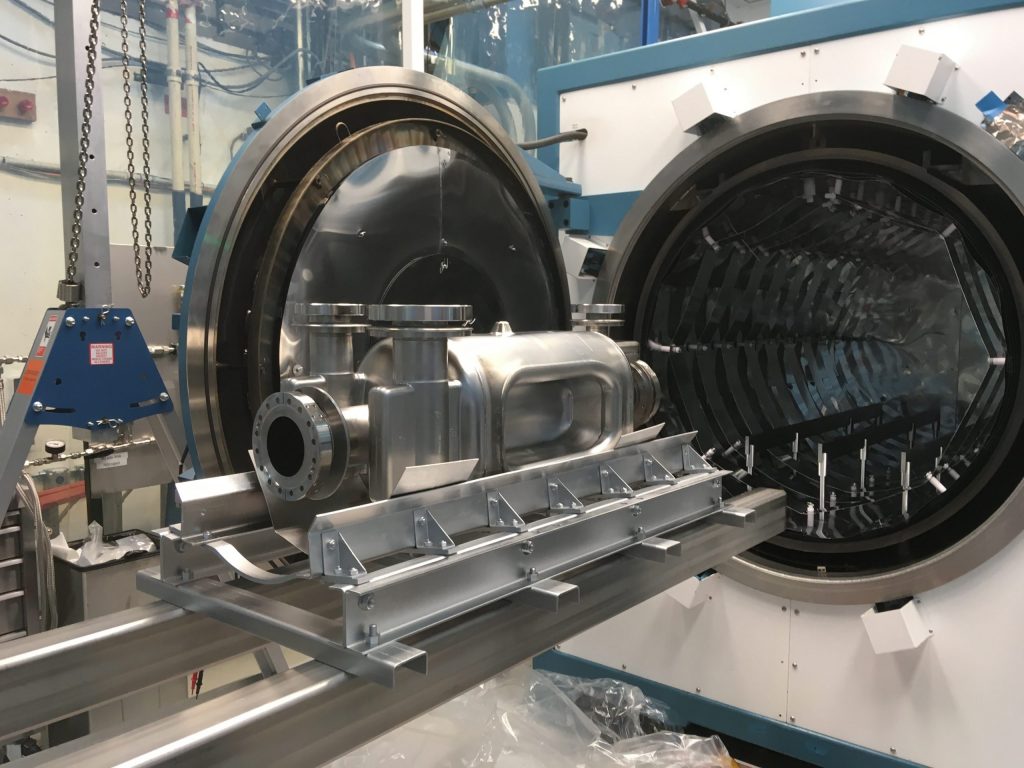

The second upgrade is a special type of accelerator cavity. Cavities are structures inside colliders that impart energy to the particle beam and propel them forward. This special cavity, called a crab cavity, is used to increase the overlap of the two beams so that more protons have a chance of colliding.

“This approval is a recognition of 15 years of research and development started by a U.S. research program and completed by this project,” said Giorgio Ambrosio, Fermilab scientist and HL-LHC AUP manager for magnets.

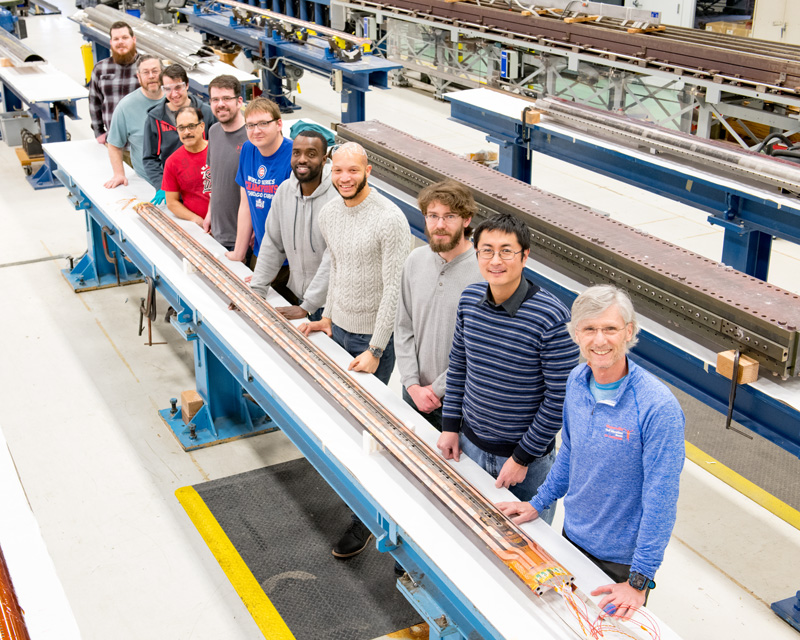

Fermilab engineers and technicians stand by a magnet coil made for the High-Luminosity LHC. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Magnets help the particles go ’round

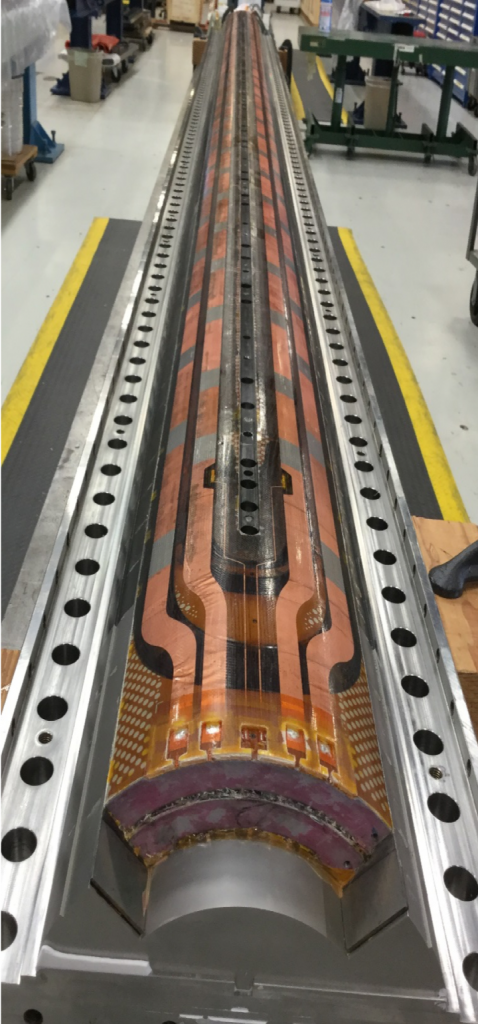

Superconducting niobium-tin magnets have never been used in a high-energy particle accelerator like the LHC. These new magnets will generate a maximum magnetic field of 12 tesla, roughly 50 percent more than the niobium-titanium magnets currently in the LHC. For comparison, an MRI’s magnetic field ranges from 0.5 to 3 tesla, and Earth’s magnetic field is only 50 millionths of one tesla.

There are multiple stages to creating the niobium-tin coils for the magnets, and each brings its challenges.

Each magnet will have four sets of coils, making it a quadrupole. Together the coils conduct the electric current that produces the magnetic field of the magnet. In order to make niobium-tin capable of producing a strong magnetic field, the coils must be baked in an oven and turned into a superconductor. The major challenge with niobium-tin is that the superconducting phase is brittle. Similar to uncooked spaghetti, a small amount of pressure can snap it in two if the coils are not well supported. Therefore, the coils must be handled delicately from this point on.

The AUP calls for 84 coils, fabricated into 21 magnets. Fermilab will manufacture 43 coils, and Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York will manufacture another 41. Those will then be delivered to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to be formed into accelerator magnets. The magnets will be sent to Brookhaven to be tested before being shipped back to Fermilab. Twenty successful magnets will be inserted into 10 containers, which are then tested by Fermilab, and finally shipped to CERN.

With CD-2/3b approval, AUP expects to have the first magnet assembled in April and tested by July. If all goes well, this magnet will be eligible for installation at CERN.

This completed niobium-tin magnet coil will generate a maximum magnetic field of 12 tesla, roughly 50 percent more than the niobium-titanium magnets currently in the LHC. Photo: Alfred Nobrega

Crab cavities for more collisions

Cavities accelerate particles inside a collider, boosting them to higher energies. They also form the particles into bunches: As individual protons travel through the cavity, each one is accelerated or decelerated depending on whether they are below or above an expected energy. This process essentially sorts the beam into collections of protons, or particle bunches.

HL-LHC puts a spin on the typical cavity with its crab cavities, which get their name from how the particle bunches appear to move after they’ve passed through the cavity. When a bunch exits the cavity, it appears to move sideways, similar to how a crab walks. This sideways movement is actually a result of the crab cavity rotating the particle bunches as they pass through.

Imagine that a football was actually a particle bunch. Typically, you want to throw a football straight ahead, with the pointed end cutting through the air. The same is true for particle bunches; they normally go through a collider like a football. Now let’s say you wanted to ensure that your football and another football would collide in mid-air. Rather than throwing it straight on, you’d want to throw the football on its side to maximize the size of the target and hence the chance of collision.

Of course, turning the bunches is harder than turning a football, as each bunch isn’t a single, rigid object.

This accelerating cavity is a type known as “crab cavity.” It is designed to maximize the chance of collision between two opposing particle beams. Photo: Paolo Berrutti

To make the rotation possible, the crab cavities are placed right before and after the collision points at two of the particle detectors at the LHC, called ATLAS and CMS. An alternating electric field runs through each cavity and “tilts” the particle bunch on its side. To do this, the front section of the bunch gets a “kick” to one side on the way in and, before it leaves, the rear section gets a “kick” to the opposite side. Now, the particle bunch looks like a football on its side. When the two bunches meet at the collision point, they overlap better, which makes the occurrence of a particle collision more likely.

After the collision point, more crab cavities straighten the remaining bunches, so they can travel through the rest of the LHC without causing unwanted interactions.

With CD-2/3b approval, all raw materials necessary for construction of the cavities can be purchased. Two crab cavity prototypes are expected by the end of 2019. Once the prototypes have been certified, the project will seek further approval for the production of all cavities destined to the LHC tunnel.

After further testing, the cavities will be sent out to be “dressed”: placed in a cooling vessel. Once the dressed cavities pass all acceptance criteria, Fermilab will ship all 10 dressed cavities to CERN.

“It’s easy to forget that these technological advances don’t benefit just accelerator programs,” said Leonardo Ristori, Fermilab engineer and an HL-LHC AUP manager for crab cavities. “Accelerator technology existed in the first TV screens and is currently used in medical equipment like MRIs. We might not be able to predict how these technologies will appear in everyday life, but we know that these kinds of endeavors ripple across industries.”