Fermilab’s largest operating neutrino experiment gains a new leader as it prepares to search for new physics that could reshape our understanding of the universe.

Tricia Vahle, Mansfield associate professor of physics at William & Mary and longtime leader and scientist on Fermilab’s NOvA neutrino experiment, was recently elected as its new co-spokesperson. She assumed her role on March 21.

Vahle joined NOvA in 2008, when it was still in its infancy — designed, but not yet built. She was instrumental in the experiment’s early years as one of the founders of a NOvA data analysis group. Later she became its analysis coordinator, overseeing teams focused on using the experiment’s data to investigate different physics phenomena.

Now, as NOvA co-spokesperson, she will lead the experiment alongside Fermilab scientist Peter Shanahan, who played a major role in completing NOvA’s construction on time and under budget and taking it into its data collection and analysis phase.

“Tricia has a huge amount of experience on NOvA, and with neutrino physics in general,” Shanahan said. “She’s been working on NOvA for many years and has a good sense of both organizational and scientific aspects of leading such an experiment.”

Vahle succeeds former co-spokesperson Mark Messier of Indiana University. Shanahan and Vahle say the collaboration is grateful to Messier for his 12 years of outstanding service to the experiment, from its design to its first scientific results, bringing the experiment to where it is today.

“Tricia is taking the helm at a really exciting time for the experiment. We’re just starting to push the experiment to answer the scientific questions it was meant to answer,” Messier said. “NOvA is moving forward into the next era of science.”

The NOvA experiment, which started up in 2014, aims to study the shape-shifting behavior of neutrinos, which are mysterious subatomic particles that could help us better understand how our universe evolved. They come in three types, and as they travel, they shift from one type into another according to so-called oscillation patterns.

To get a better handle on how they oscillate, scientists study how neutrinos change over long distances: Fermilab’s powerful particle accelerators send a beam of neutrinos 500 miles from the lab (just outside Chicago, Illinois) straight through Earth to a giant neutrino detector in Ash River, Minnesota. Scientists compare the measurements made at Fermilab to those in Minnesota.

After four years of taking data on neutrinos, NOvA recently shifted to recording data on their antimatter counterparts, antineutrinos. Differences in the oscillations of the two particles could solve the mystery of why there is an asymmetry between matter and antimatter in our universe. They could also reveal new physics.

“It’s a very exciting time because we’re on the verge of realizing NOvA’s full physics potential,” Vahle said. “We’re looking forward to using more sensitive data analyses to study both antineutrinos and neutrinos and compare them.”

NOvA, which is made up of almost 250 scientists from 48 institutions around the world, will continue to run until at least 2024, switching between antineutrino and neutrino measurements to obtain roughly equal amounts of data for each. NOvA will also focus on making ever more precise measurements of neutrinos’ basic properties, such as the relationship between the masses of the different types.

“My goal in the near future is to work together with Tricia, the collaboration and Fermilab to meet the challenge of furthering our understanding of neutrino physics,” Shanahan said. “Our work ahead will focus on getting the most possible data for NOvA and making the most of it through ongoing improvements to our analysis.”

Vahle says she’s happy to be at the forefront of potential neutrino discovery.

“In the long term, we aim to keep people excited about our experiment and the top-notch physics we are doing,” Vahle said.

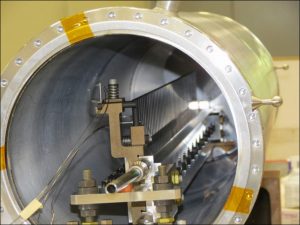

The high-energy NOvA target at Fermilab is made of tall graphite fins, lined up like dominoes, shown here inside its water-cooled outer vessel. Photo: Patrick Hurh

For some, a target is part of a game of darts. For others, it’s a retail chain. In particle physics, it’s the site of an intense, complex environment that plays a crucial role in generating the universe’s smallest components for scientists to study.

The target is an unsung player in particle physics experiments, often taking a back seat to scene-stealing light-speed particle beams and giant particle detectors. Yet many experiments wouldn’t exist without a target. And, make no mistake, a target that holds its own is a valuable player.

Scientists and engineers at Fermilab are currently investigating targets for the study of neutrinos — mysterious particles that could hold the key to the universe’s evolution.

Intense interactions

The typical particle physics experiment is set up in one of two ways. In the first, two energetic particle beams collide into each other, generating a shower of other particles for scientists to study.

In the second, the particle beam strikes a stationary, solid material — the target. In this fixed-target setup, the powerful meeting produces the particle shower.

As the crash pad for intense beams, a target requires a hardy constitution. It has to withstand repeated onslaughts of high-power beams and hold up under hot temperatures.

You might think that, as stalwart players in the play of particle production, targets would look like a fortress wall (or maybe you imagined dartboard). But targets take different shapes — long and thin, bulky and wide. They’re also made of different materials, depending on the kind of particle one wants to make. They can be made of metal, water or even specially designed nanofibers.

In a fixed-target experiment, the beam — say, a proton beam — races toward the target, striking it. Protons in the beam interact with the target material’s nuclei, and the resulting particles shoot away from the target in all directions. Magnets then funnel and corral some of these newly born particles to a detector, where scientists measure their fundamental properties.

The particle birthplace

Keith Anderson, Fermilab senior technical aide for the NOvA target, works on its installation. Photo: Reidar Hahn

The particles that emerge from the beam-target interaction depend in large part on the target material. Consider Fermilab neutrino experiments.

In these experiments, after the protons strike the target, some of the particles in the subsequent particle shower decay — or transform — into neutrinos.

The target has to be made of just the right stuff.

“Targets are crucial for particle physics research,” said Fermilab scientist Bob Zwaska. “They allow us to create all of these new particles, such as neutrinos, that we want to study.”

Graphite is a goldilocks material for neutrino targets. If kept at the right temperature while in the proton beam, the graphite generates particles of just the right energy to be able to decay into neutrinos.

For neutron targets, such as that at the Spallation Neutron Source at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, heavier metals such as mercury are used instead.

Maximum interaction is the goal of a target’s design. The target for Fermilab’s NOvA neutrino experiment, for example, is a straight row — about the length of your leg — of graphite fins that resemble tall dominoes. The proton beam barrels down its axis, and every encounter with a fin produces an interaction. The thin shape of the target ensures that few of the particles shooting off after collision are reabsorbed back into the target.

Robust targets

“As long as the scientists have the particles they need to study, they’re happy. But down the line, sometimes the targets become damaged,” said Fermilab engineer Patrick Hurh. In such cases, engineers have to turn down — or occasionally turn off — the beam power. “If the beam isn’t at full capacity or is turned off, we’re not producing as many particles as we can for science.”

The more protons that are packed into the beam, the more interactions they have with the target, and the more particles that are produced for research. So targets need to be in tip-top shape as much as possible. This usually means replacing targets as they wear down, but engineers are always exploring ways of improving target resistance, whether it’s through design or material.

Consider what targets are up against. It isn’t only high-energy collisions — the kinds of interactions that produce particles for study — that targets endure.

Lower-energy interactions can have long-term, negative impacts on a target, building up heat energy inside it. As the target material rises in temperature, it becomes more vulnerable to cracking. Expanding warm areas hammer against cool areas, creating waves of energy that destabilize its structure.

Some of the collisions in a high-energy beam can also create lightweight elements such as hydrogen or helium. These gases build up over time, creating bubbles and making the target less resistant to damage.

A proton from the beam can even knock off an entire atom, disrupting the target’s crystal structure and causing it to lose durability.

Clearly, being a target is no picnic, so scientists and engineers are always improving targets to better roll with a punch.

For example, graphite, used in Fermilab’s neutrino experiments, is resistant to thermal strain. And, since it is porous, built-up gases that might normally wedge themselves between atoms and disrupt their arrangement may instead migrate to open areas in the atomic structure. The graphite is able to remain stable and withstand the waves of energy from the proton beam.

Engineers also find ways to maintain a constant target temperature. They design it so that it’s easy to keep cool, integrating additional cooling instruments into the target design. For example, external water tubes help cool the target for Fermilab’s NOvA neutrino experiment.

Targets for intense neutrino beams

At Fermilab, scientists and engineers are also testing new designs for what will be the lab’s most powerful proton beam — the beam for the laboratory’s flagship Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility and Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, known as LBNF/DUNE.

LBNF/DUNE is scheduled to begin operation in the 2020s. The experiment requires an intense beam of high-energy neutrinos — the most intense in the world. Only the most powerful proton beam can give rise to the quantities of neutrinos LBNF/DUNE needs.

Scientists are currently in the early testing stages for LBNF/DUNE targets, investigating materials that can withstand the high-power protons. Currently in the running are beryllium and graphite, which they’re stretching to their limits. Once they conclusively determine which material comes out on top, they’ll move to the design prototyping phase. So far, most of their tests are pointing to graphite as the best choice.

Targets will continue to evolve and adapt. LBNF/DUNE provides just one example of next-generation targets.

“Our research isn’t just guiding the design for LBNF/DUNE,” Hurh said. “It’s for the science itself. There will always be different and more powerful particle beams, and targets will evolve to meet the challenge.”

New result draws on 30 years of research and development and begins the definitive search for axion particles

A cutaway rendering of the ADMX detector, which can detect axions producing photons inside its cold, dark interior. Image: ADMX collaboration

Forty years ago, scientists theorized a new kind of low-mass particle that could solve one of the enduring mysteries of nature: what dark matter is made of. Now a new chapter in the search for that particle has begun.

This week, the Axion Dark Matter Experiment (ADMX) unveiled a new result, published in Physical Review Letters, that places it in a category of one: It is the world’s first and only experiment to have achieved the necessary sensitivity to “hear” the telltale signs of dark matter axions. This technological breakthrough is the result of more than 30 years of research and development, with the latest piece of the puzzle coming in the form of a quantum-enabled device that allows ADMX to listen for axions more closely than any experiment ever built.

ADMX is managed by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and located at the University of Washington. This new result, the first from the second-generation run of ADMX, sets limits on a small range of frequencies where axions may be hiding and sets the stage for a wider search in the coming years.

“This result signals the start of the true hunt for axions,” said Fermilab scientist Andrew Sonnenschein, the operations manager for ADMX. “If dark matter axions exist within the frequency band we will be probing for the next few years, then it’s only a matter of time before we find them.”

One theory suggests that the dark matter that holds galaxies together might be made up of a vast number of low-mass particles, which are almost invisible to detection as they stream through the cosmos. Efforts in the 1980s to find this particle, named the axion by theorist Frank Wilczek, currently of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, were unsuccessful, showing that their detection would be extremely challenging.

Inside the ADMX experiment hall at the University of Washington. The ADMX detector is underground, surrounded by a magnetic field. Photo: Mark Stone/University of Washington

ADMX is an axion haloscope — essentially a large, low-noise radio receiver, which scientists tune to different frequencies and listen to to find the axion signal frequency. Axions almost never interact with matter, but with the aid of a strong magnetic field and a cold, dark, properly tuned, reflective box, ADMX can “hear” photons created when axions convert into electromagnetic waves inside the detector.

“If you think of an AM radio, it’s exactly like that,” said Gray Rybka, co-spokesperson for ADMX and assistant professor at the University of Washington. “We’ve built a radio that looks for a radio station, but we don’t know its frequency. We turn the knob slowly while listening. Ideally we will hear a tone when the frequency is right.”

This detection method, which might make the “invisible axion” visible, was invented by Pierre Sikivie of the University of Florida in 1983, as was the notion that galactic halos could be made of axions. Pioneering experiments and analyses by a collaboration of Fermilab, the University of Rochester and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, as well as scientists at the University of Florida, demonstrated the practicality of the experiment. This led to the construction in the late 1990s of a large-scale detector at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory that is the basis of the current ADMX.

It was only recently, however, that the ADMX team has been able to deploy superconducting quantum amplifiers to their full potential, enabling the experiment to reach unprecedented sensitivity. Previous runs of ADMX were stymied by background noise generated by thermal radiation and the machine’s own electronics.

Fixing thermal radiation noise is easy: a refrigeration system cools the detector down to 0.1 Kelvin (roughly minus 460 degrees Fahrenheit). But eliminating the noise from electronics proved more difficult. The first runs of ADMX used standard transistor amplifiers, but after connecting with John Clarke, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Clarke developed a quantum-limited amplifier for the experiment. This much quieter technology, combined with the refrigeration unit, reduces the noise by a significant enough level that the signal, should ADMX discover one, will come through loud and clear.

“The initial versions of this experiment, with transistor-based amplifiers, would have taken hundreds of years to scan the most likely range of axion masses. With the new superconducting detectors, we can search the same range on time scales of only a few years,” said Gianpaolo Carosi, co-spokesperson for ADMX and scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

ADMX will now test millions of frequencies at this level of sensitivity. If axions are found, it would be a major discovery that could explain not only dark matter, but other lingering mysteries of the universe. If ADMX does not find axions, that may force theorists to devise new solutions to those riddles.

“A discovery could come at any time over the next few years,” said scientist Aaron Chou of Fermilab. “It’s been a long road getting to this point, but we’re about to begin the most exciting time in this ongoing search for axions.”

Read the Physical Review Letters paper. Read more about the Axion Dark Matter Experiment.

This research is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, the Heising-Simons Foundation and research and development programs at the U.S. DOE’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the U.S. DOE’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

The ADMX collaboration includes scientists at Fermilab, the University of Washington, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, the University of California at Berkeley, the University of Chicago, the University of Florida and the University of Sheffield.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC, a joint partnership between the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association, Inc. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

The University of Washington was founded in 1861 and is one of the pre-eminent public higher education and research institutions in the world. The UW has more than 100 members of the National Academies, elite programs in many fields, and annual standing since 1974 among the top five universities in receipt of federal research funding. Learn more at www.uw.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

The Heising-Simons Foundation is a family foundation based in Los Altos, California, enabling groundbreaking research in science, among other issues. For more information, please visit hsfoundation.org.

MiniBooNE scientists demonstrate a new way to probe the nucleus with muon neutrinos.

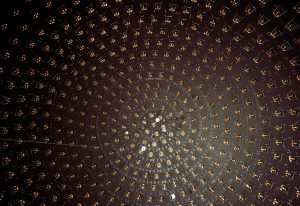

This interior view of the MiniBooNE detector tank shows the array of photodetectors used to pick up the light particles that are created when a neutrino interacts with a nucleus inside the tank. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Tiny particles known as neutrinos are an excellent tool to study the inner workings of atomic nuclei. Unlike electrons or protons, neutrinos have no electric charge, and they interact with an atom’s core only via the weak nuclear force. This makes them a unique tool for probing the building blocks of matter. But the challenge is that neutrinos are hard to produce and detect, and it is very difficult to determine the energy that a neutrino has when it hits an atom.

This week a group of scientists working on the MiniBooNE experiment at the Department of Energy’s Fermilab reported a breakthrough: They were able to identify exactly-known-energy muon neutrinos hitting the atoms at the heart of their particle detector. The result eliminates a major source of uncertainty when testing theoretical models of neutrino interactions and neutrino oscillations.

“The issue of neutrino energy is so important,” said Joshua Spitz, Norman M. Leff assistant professor at the University of Michigan and co-leader of the team that made the discovery, along with Joseph Grange at Argonne National Laboratory. “It is extraordinarily rare to know the energy of a neutrino and how much energy it transfers to the target atom. For neutrino-based studies of nuclei, this is the first time it has been achieved.”

To learn more about nuclei, physicists shoot particles at atoms and measure how they collide and scatter. If the energy of a particle is sufficiently large, a nucleus hit by the particle can break apart and reveal information about the subatomic forces that bind the nucleus together.

But to get the most accurate measurements, scientists need to know the exact energy of the particle breaking up the atom. That, however, is almost never possible when doing experiments with neutrinos.

Like other muon neutrino experiments, MiniBooNE uses a beam that comprises muon neutrinos with a range of energies. Since neutrinos have no electric charge, scientists have no “filter” that allows them to select neutrinos with a specific energy.

MiniBooNE scientists, however, came up with a clever way to identify the energy of a subset of the muon neutrinos hitting their detector. They realized that their experiment receives some muon neutrinos that have the exact energy of 236 million electronvolts (MeV). These neutrinos stem from the decay of kaons at rest about 86 meters from the MiniBooNE detector emerging from the aluminum core of the particle absorber of the NuMI beamline, which was built for other experiments at Fermilab.

Energetic kaons decay into muon neutrinos with a range of energies. The trick is to identify muon neutrinos that emerge from the decay of kaons at rest. Conservation of energy and momentum then require that all muon neutrinos emerging from the kaon-at-rest decay have to have exactly the energy of 236 MeV.

“It is not often in neutrino physics that you know the energy of the incoming neutrino,” said MiniBooNE co-spokesperson Richard Van De Water of Los Alamos National Laboratory. “With the first observation by MiniBooNE of monoenergetic muon neutrinos from kaon decay, we can study the charged current interactions with a known probe that enable theorists to improve their cross section models. This is important work for the future short- and long-baseline neutrino programs at Fermilab.”

This analysis was conducted with data collected from 2009 to 2011.

“The result is notable,” said Rex Tayloe, co-spokesperson of the MiniBooNE collaboration and professor of physics at Indiana University Bloomington. “We were able to extract this result because of the well-understood MiniBooNE detector and our previous careful studies of neutrino interactions over 15 years of data collection.”

Spitz and his colleagues already are working on the next monoenergetic neutrino result. A second neutrino detector located near MiniBooNE, called MicroBooNE, also receives muon neutrinos from the NuMI absorber, 102 meters away. Since MicroBooNE uses liquid-argon technology to record neutrino interactions, Spitz is optimistic that the MicroBooNE data will provide even more information.

“MicroBooNE will provide more precise measurements of this known-energy neutrino,” he said. “The results will be extremely valuable for future neutrino oscillation experiments.”

The MiniBooNE result was published in the April 6, 2018, issue of Physical Review Letters. This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.