Fermilab’s annual Family Open House took place on Sunday, Feb. 11.

This year’s event featured the show “Colder than Cool.” Attendees got to see everyday objects dunked or soused with liquid nitrogen and see its uses in electricity and magnetism. They also participated in the “Live from CERN” event, taking a virtual tour of the CMS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider and ask questions of scientists at Fermilab and in Geneva, Switzerland. They enjoyed presentations on the physics and engineering of sports and a panel on women in science. Scientist and engineers answered questions in the exhibit area on the 15th floor of Wilson Hall. And a panel of lab employees presented an interactive talk about their day-to-day jobs.

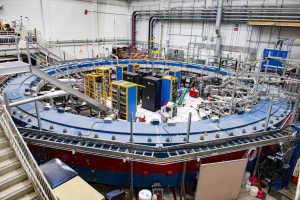

Operators at Remote Operations Center East (operations center for the CMS experiment in Geneva) and Remote Operations Center West (center for the laboratory’s neutrino experiments) discussed their work with Open House participants. Participants also toured the Linear Accelerator, the Main Control Room and the Muon g-2 experiment.

High schools hosted interactive exhibits in the Wilson Hall atrium. They were Downers Grove North, Auburn High School (Rockford), West Aurora High School and Islamic Foundation School (Villa Park).

The Family Open House is made possible by an anonymous donor to the nonprofit organization Fermilab Friends for Science Education.

The following press release on the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) was issued by the DESI collaboration. The U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab is a member of the collaboration, bringing expertise gained during the design, building and operation of the Dark Energy Camera to this next-generation instrument.

Fermilab scientists are managing key elements of the construction, including the heavy mechanical components (including the precise alignment of the structures that hold the lenses), the assembly of the charge-coupled devices, or CCDs, that capture light, and the online databases used for data acquisition. Fermilab is also providing software that maps between the locations of light sources in the sky and the positions of each of the 5,000 robotic fiber positioners that make up the DESI plane, drawing on more than 25 years of experience with the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the Dark Energy Survey.

For more information on Fermilab’s role in DESI, please contact Andre Salles at media@fnal.gov or 630-840-3351.

Solving the dark energy mystery: a new assignment for a 45-year-old telescope

Kitt Peak National Observatory prepares for the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument

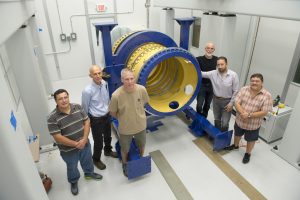

Members of the Fermilab team stand with the lens-holding barrel for the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument. From left: Jorge Montes, Mike Roman, David Butler, Gaston Gutierrez, Giuseppe Gallo and Otto Alvarez. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Forty-five years ago this month, a telescope tucked inside a 14-story, 500-ton dome atop a mile-high peak in Arizona took in the night sky for the first time and recorded its observations in glass photographic plates.

Today, the dome closes on the previous science chapters of the 4-meter Nicholas U. Mayall Telescope so that it can prepare for its new role in creating the largest 3-D map of the universe. This map could help to solve the mystery of dark energy, which is driving the accelerating expansion of the universe.

The temporary closure sets in motion the largest overhaul in the telescope’s history and sets the stage for the installation of the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), which will begin a five-year observing run next year at the National Science Foundation’s Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO) —part of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO).

“This day marks an enormous milestone for us,” said DESI Director Michael Levi of the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), which is leading the project’s international collaboration. “Now we remove the old equipment and start the yearlong process of putting the new stuff on.”

More than 465 researchers from about 71 institutions are participating in the DESI collaboration.

The entire top end of the telescope, which weighs as much as a school bus and houses the telescope’s secondary mirror and a large digital camera, will be removed and replaced with DESI instruments, noted KPNO Director Lori Allen. A large crane will lift the telescope’s top end through the observing slit in its dome.

David Sprayberry, KPNO site director for DESI, said, “The Mayall is being readied for an exciting second career probing the role of dark energy in the expansion history of the universe.”

Fermilab built the lens-holding barrel of the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Besides providing new insights about the universe’s expansion and large-scale structure, DESI will also help to set limits on theories related to gravity and the formative stages of the universe and could even provide new mass measurements for a variety of elusive yet abundant subatomic particles called neutrinos.

“One of the primary ways that we learn about the unseen universe is by its subtle effects on the clustering of galaxies,” said DESI Collaboration Co-spokesperson Daniel Eisenstein of Harvard University. “The new maps from DESI will provide an exquisite new level of sensitivity in our study of cosmology.”

The Mayall Telescope has played an important role in many astrophysics discoveries, including measurements supporting the discovery of dark energy and establishing the role of dark matter in the universe from measurements of galaxy rotation. Its observations have also been used in determining the scale and structure of the universe. Dark matter and dark energy together are believed to make up about 95 percent of all of the universe’s mass and energy.

It was one of the world’s largest optical telescopes at the time it was built, and because of its sturdy construction it is perfectly suited to carry the new 9-ton instrument.

“We started this project by surveying large telescopes to find one that had a suitable mirror and wouldn’t collapse under the weight of such a massive instrument,” said Berkeley Lab’s David Schlegel, a DESI project scientist.

Arjun Dey, the NOAO project scientist for DESI, explained, “The Mayall was precociously engineered like a battleship and designed with a wide field of view.”

Allen added, “The redesign maintains the original intent of the facility as a wide-field telescope, but we are now taking that to its practical limit.”

The expansion of the telescope’s field-of-view will allow DESI to map out about one-third of the sky.

Brenna Flaugher, a DESI project scientist who leads the Astrophysics Department at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, said DESI will transform the speed of science at the Mayall Telescope.

“The telescope was designed to carry a person at the top who aimed and steered it, but with DESI it’s all automated,” she said. “Instead of one at a time, we can measure the velocities of 5,000 galaxies at a time — we will measure more than 30 million of them in our five-year survey.”

Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona will soon house the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument. Photo courtesy of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

DESI will use an array of 5,000 swiveling robots, each carefully choreographed to point a fiber-optic cable at a preprogrammed sequence of deep-space objects, including millions of galaxies and quasars, which are galaxies that harbor massive, actively feeding black holes.

The fiber-optic cables will carry the light from these objects to 10 spectrographs, which are tools that will measure the properties of this light and help to pinpoint the objects’ distance and the rate at which they are moving away from us. DESI’s observations will provide a deep look into the early universe, up to about 11 billion years ago.

The cylindrical, fiber-toting robots, which will be embedded in a rounded metal unit called a focal plane, will reposition to capture a new exposure of the sky roughly every 20 minutes. The focal plane is expected to be completed and delivered to Kitt Peak this year.

DESI will scan one-third of the sky and will capture about 10 times more data than a predecessor survey, the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS). That project relied on a manually rotated sequence of metal plates — with fibers plugged by hand into predrilled holes – to target objects.

All of DESI’s six lenses, each about a meter in diameter, are complete. They will be carefully stacked and aligned in a steel support structure and will ultimately ride with the focal plane atop the telescope.

Each of these lenses took shape from large blocks of glass. They have criss-crossed the globe to receive various treatments, including grinding, polishing and coatings. It took about three-and-a-half years to produce each of the lenses, which now reside at University College London in the UK, and will be shipped to the DESI site this spring.

The Mayall Telescope has most recently been enlisted in a DESI-supporting sky survey known as the Mayall z-Band Legacy Survey (MzLS), which is one of four sky surveys that DESI will use to preselect its targeted sky objects. That survey wrapped up just days before the Mayall’s temporary closure, while the others are ongoing.

Data from these surveys are analyzed at Berkeley Lab’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science user facility. Data from these surveys have been released to the public at http://legacysurvey.org.

“We can see about a billion galaxies in the survey images, which is quite a bit of fun to explore,” Schlegel said. “The DESI instrument will precisely measure millions of those galaxies to see the effects of dark energy.”

Installation of DESI’s components is expected to begin soon and to wrap up in April 2019, with first science observations planned in September 2019.

“Installing DESI on the Mayall will put the telescope at the heart of the next decade of discoveries in cosmology,” said Risa Wechsler, DESI collaboration co-spokesperson and associate professor of physics and astrophysics at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. “The amazing 3-D map it will measure may solve some of the biggest outstanding questions in cosmology, or surprise us and bring up new ones.”

DESI is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science; the U.S. National Science Foundation, Division of Astronomical Sciences under contract to the National Optical Astronomy Observatory; the Science and Technologies Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; the Heising-Simons Foundation; the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico; the Ministry of Economy of Spain; and DESI member institutions. The DESI scientists are honored to be permitted to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak), a mountain with particular significance to the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Current DESI Member Institutions include: Aix-Marseille University; Argonne National Laboratory; Barcelona-Madrid Regional Participation Group; Brookhaven National Laboratory; Boston University; Carnegie Mellon University; CEA-IRFU, Saclay; China Participation Group; Cornell University; Durham University; École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne; Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, Zürich; Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory; Granada-Madrid-Tenerife Regional Participation Group; Harvard University; Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute; Korea Institute for Advanced Study; Institute of Cosmological Sciences, University of Barcelona; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; Laboratoire de Physique Nucléaire et de Hautes Energies; Mexico Regional Participation Group; National Optical Astronomy Observatory; Ohio University; Siena College; SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory; Southern Methodist University; Swinburne University; The Ohio State University; Universidad de los Andes; University of Arizona; University of California, Berkeley; University of California, Irvine; University of California, Santa Cruz; University College London; University of Michigan at Ann Arbor; University of Pennsylvania; University of Pittsburgh; University of Portsmouth; University of Queensland; University of Rochester; University of Toronto; University of Utah; University of Zurich; UK Regional Participation Group; Yale University. For more information, visit desi.lbl.gov.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC, a joint partnership between the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association Inc. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

The National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO) is the national center for ground-based nighttime astronomy in the United States (www.noao.edu) and is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation Division of Astronomical Sciences.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency created by Congress in 1950 to promote the progress of science. NSF supports basic research and people to create knowledge that transforms the future.

Established in 2007 by Mark Heising and Elizabeth Simons, the Heising-Simons Foundation (www.heisingsimons.org) is dedicated to advancing sustainable solutions in the environment, supporting groundbreaking research in science, and enhancing the education of children.

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, established in 2000, seeks to advance environmental conservation, patient care and scientific research. The Foundation’s Science Program aims to make a significant impact on the development of provocative, transformative scientific research, and increase knowledge in emerging fields. For more information, visit www.moore.org. The Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) of the United Kingdom coordinates research on some of the most significant challenges facing society, such as future energy needs, monitoring and understanding climate change, and global security. It offers grants and support in particle physics, astronomy and nuclear physics, visit http://www.stfc.ac.uk.

Editor’s note: With Feb. 11 marking the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, female physicists, engineers and computer scientists from CERN and from Fermilab share their experiences of building a career in science.

Krista Majewski

Krista Majewski: “What I like about programming is the breaking down of problems and being able to solve things.”

Krista Majewski came to Fermilab nine years ago as a software developer and now works in an operations role. She is a computing services specialist and part of the grid and cloud operations group, which manages computing clusters for the CMS experiment and other intensity frontier experiments at the lab.

“My typical day would be maintaining the services that our group is responsible for and the machines that they run on. So if there are problems with a computing cluster where a user can’t run their jobs, or they’re trying to run on resources on the grid and they’re unable to, then our group would be responsible for helping debug some of those issues,” Majewski said.

Her path to programming at Fermilab has been winding. After receiving a degree in biomedical engineering, she went to work doing web development and programming for a large consulting firm, then moved to the financial industry. But programming called her back, and she earned a master’s degree in computer science to start her new career.

For Majewski, programming is similar to something she enjoyed as child: solving puzzles.

“I think it’s a skill that you use in a lot of different ways,” Majewski said.

Sofia Vallecorsa

Sofia Vallecorsa: “Technology is part of society, so learning computing can be empowering.” Photo: CERN

Italian physicist Sofia Vallecorsa always knew that she wanted to study science. Her mother was a physicist and her father a mathematician, so it felt natural to her to choose a physics degree. During her studies she saw computing simply as a tool, but as time went on her love for computing grew. Computing was interesting because it was challenging.

“Coding reminded me of being a kid playing with a challenging problem. It felt so rewarding when I found the solution,” Vallecorsa said.

After her studies she moved into computing and now works in the CERN Physics Department providing software tools for the experimental physicists. Coming to computing via a different background meant making more effort to learn things for herself. But this taught her to face challenges one step at a time to reach her goal.

“I use a lot of machine learning in my work, and this was something that I had to learn from scratch. Yet it is so interesting and important to many fields and has really expanded my horizons to work with experts outside of particle physics,” she said.

Margherita Vittone-Wiersma

Margherita Vittone-Wiersma came to Fermilab as a physicist in February 1985. Together with a group of researchers from Italy’s Institute of Nuclear Physics, she began a new experiment called E 687. But she soon learned that she preferred working on data acquisition and the many methods to store and access the huge amount of data coming out of science experiments. What was once mere megabytes of data is now terabytes of information — and experimental physicists need to be able to retrieve stored data and monitor data coming from the detectors in real time.

“It’s been an incredible change in scale of the amount of data that is handled by computers and has to be analyzed by the physicists” Vittone-Wiersma said.

Vittone-Wiersma migrated from physics to her new role in computing through lots of hands-on learning and classes in different programming languages and software development offered at Fermilab. She officially joined the lab’s Computing Division in 1989.

“It’s a great experience to work with the physicists,” she said. Together physicists and computing experts iterate over tools “to make sure that everything is working the way they expect. It’s very rewarding.”

Sima Baymani

Sima Baymani: “You can work all over the world, because programming is the same everywhere. The choices you have are endless.” Photo: CERN

Computer science engineer Sima Baymani was born in Iran before her family fled war when she was young to start a new life in Sweden. Her parents were academics, and Baymani and her sisters were always encouraged to learn more about everything. Her mother, a physicist, had to restart her career in Sweden and chose to pursue database management and programming. Her enjoyment of her job, coupled with an inspiring Danish mathematics teacher, were two factors that helped lead Baymani towards studying computer science.

“In school I was interested in almost all subjects. But I can see that the IT boom in Sweden had an effect on me and on other women, because when we started university it was one of the peaks of women studying computer science,” she said.

At university, Baymani wanted to understand how computers worked, so she specialized in hardware and embedded systems. After graduation she worked as an independent consultant for 10 years before joining CERN.

“You can work all over the world, because programming is the same everywhere. If you value freedom and flexibility then programming is something for you – it’s really something that anyone can pursue if they want to,” Baymani said.

She has encountered challenges in fighting gender and ethnic stereotypes, and often felt that she had to work harder to prove herself. Yet part of her joy of programming is collaborating with colleagues to find creative solutions to complex problems and to develop new products or new functionality.

“Technology is everywhere in our society; the problems and solutions you can work with creatively are endless,” she said.

Jeny Teheran

Jeny Teheran is a security analyst and cybersecurity researcher at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. That means keeping up with and taking care of hardware and software vulnerabilities so that the experiments can carry out their science in a secure manner. It’s a fast-paced job where you have to come with the best solution you can put in place, right in the moment. “I would recommend this job because it challenges you. It pushes you to be on top of your game. You have to improve your analytical skills; you have to react fast; you have to communicate better,” Teheran said. Teheran came to Fermilab from the Caribbean coast of Colombia. She grew up in a house with few toys but lots of books, and says she has always felt close to science. With a degree in systems and computing engineering, she arrived at Fermilab four years ago as an intern to work on the offline production team for neutrino experiments. A year later, she was hired as a security analyst. “And I’m loving it,” she said.

Evangelia Gousiou

Evangelia Gousiou (right): “Nothing beats the rush you get when something that you designed works for the first time,” she said. Photo: Jacques Fichet/CERN

Electronics engineer Evangelia Gousiou began her career studying IT and electronics in Athens, Greece, before beginning an internship at a manufacturing plant in Thailand. She came to CERN for a one-year position, and now, 10 years later, is still at CERN enjoying a job that is never boring.

“Work is never repetitive, which makes it very rewarding. I usually follow a project through all its stages from conception of the architecture, to the coding and the delivery to the users of a product that I have built to be useful for them. So I see the full picture and that keeps me engaged,” Gousiou said.

For Gousiou, to be a good electronics engineer means knowing a range of disciplines, from software to mechanics. There is also the human aspect, as she works daily with people from many different cultures.

At school, her favorite subjects were math and physics, as she enjoyed finding out how things worked, yet Gousiou never dreamed of being an engineer when she grew up. When the time came to choose what to study, she felt that engineering would be something interesting to study and future-proof, and then she got hooked and now can’t imagine doing anything else.

“I would recommend engineering professions for their intellectual challenge and the empowerment that they bring,” she beams.

Fermilab’s Muon g-2 experiment has officially begun taking data. Pictured here is the centerpiece of the experiment, a 50-foot-wide electromagnet ring, which generates a uniform magnetic field so scientists can make measurements of particles called muons with immense precision. Photo: Reidar Hahn

The Muon g-2 experiment at Fermilab, which has been six years in the making, is officially up and running after reaching its final construction milestone. The U.S. Department of Energy on Jan. 16 granted the last of five approval stages to the project, Critical Decision 4 (CD-4), formally allowing its transition into operations.

“We laid down the plans for Muon g-2 early on and have stuck to that through four years of construction,” said Fermilab’s Chris Polly, the experiment’s co-spokesperson and former project manager. “We’ve come out on schedule and under budget, which sets a good precedent for all the other projects.”

The experiment will send particles called muons — heavier cousins of the electron — around a 50-foot-wide muon storage ring that was relocated from Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York state in 2013. The uniform magnetic field inside the ring exerts a torque that affects the muons’ own spins, causing them to wobble. In the early 2000s, scientists at Brookhaven found the value of this wobble, called magnetic precession, to be different from the “g-2” value predicted by theory.

At Fermilab, the Muon g-2 experiment aims to confirm or refute this intriguing discrepancy with theory by repeating the measurements with a fourfold improvement in accuracy, up to 140 parts per billion. That’s like measuring the length of a football field with a margin of error that is only one-tenth the thickness of a human hair. If the experimental deviation from theory turns out to be real, it would mean that undiscovered forces or particles beyond the Standard Model — the theoretical framework that describes how the universe works — are appearing and disappearing from the vacuum to disturb the muons’ magnetic moment.

And if it isn’t?

“Well, if we find the measurement is consistent with theory, it will allow us to narrow our search for new physics, since it will rule out some current models that would no longer be viable,” Polly said.

For example, Polly added, there are theories positing the existence of supersymmetric particles — superheavy partners to those in the Standard Model — and new categories of particles that could be the constituents of the mysterious dark matter, which makes up 80 percent of the universe’s mass. Some of these theories would no longer be valid.

“That’s the value of a null result,” Polly said. “It helps us make sure that the theories that we would use to try to understand these other bigger questions are consistent.”

All that’s left now is to finish fine-tuning the instruments so the experiment can start its several-year run of data collection.

“For most of the team, this was the first project we’ve worked on,” said Fermilab physicist Mary Convery, who served as the experiment’s deputy project manager. “To see it through from design to construction and now to operations has been very rewarding.”

Muon g-2 operations got a head start in June 2017, when the team fired up the particle beam to start calibrating the detectors and tweaking components that required additional work.

“Since the accelerator turned back on in November, we have been commissioning the beamlines, the storage ring and the rest of the experiment,” said University of Washington physicist David Hertzog, Muon g-2 co-spokesperson.

As early as next month, Muon g-2 will be ready to start collecting physics-quality data at Fermilab and explore the nature of the previously measured g-2 discrepancy.

“We’ve set ourselves the goal of collecting three times the amount of data that they had in Brookhaven’s three-year run during this first spring season,” Hertzog said. “But this is just the very beginning: The experiment will run with higher intensity next year. The ultimate goal is to collect 21 times the Brookhaven statistics.”

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC, a joint partnership between the University of Chicago and the Universities Research Association Inc. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov.

Robert Wilson would be proud.

When Wilson, Fermilab’s founding director, was setting forth his plans for a new particle physics laboratory 50 years ago, he envisioned an architecturally significant built environment.

“My fantasy of a utopian laboratory clearly required a setting of environmental beauty, of architectural grandeur, of cultural splendor,” he wrote in 1987.

In 2017, Fermilab saw the completion of two new buildings for its Short-Baseline Neutrino program, striking structures that house the SBN’s neutrino detectors. The buildings were so impressive that the Association of Licensed Architects awarded Holabird & Root, the architecture firm that designed them, a Gold Award through ALA’s 2017 Design Awards Program.

The award recognized the ingenuity not only in creating highly flexible spaces to house the particle detectors, but also in incorporating visual representations of neutrino science.

“It’s easy just to make a box like a warehouse, but our collaboration has allowed us to make a space that’s much more than that,” said Fermilab’s Steve Dixon, project manager for the SBN detector buildings.

In 2015, Fermilab and Holabird & Root partnered to design and construct the buildings that would house two of the three neutrino detectors used in the SBN program.

In the planned SBN program, Fermilab will send a beam of neutrinos — subtle, mysterious subatomic particles — through three detectors, one positioned behind the other, in the path of the beam. Scientists will study the data recorded by the detectors to paint a more detailed picture of the neutrino, whose various properties have eluded precise depiction, thanks to their fleeting nature.

Holabird & Root would design buildings for the detectors called ICARUS and SBND. ICARUS was originally used in experiments at INFN’s Italian Gran Sasso laboratory. After a period of refurbishment at the European laboratory CERN, it was delivered to Fermilab, where it arrived last year. The second detector, the Short-Baseline Near Detector or SBND, is currently under construction. (The third, called MicroBooNE, is already in operation.)

Holabird & Root is a historic Chicago architectural firm renowned for their designs around the world, including the Chicago Board of Trade Building and Soldier Field in Chicago, among others. The firm has worked with Fermilab for almost 18 years on various projects and designed the SBN buildings with particle physics in mind.

“The project depended on the translation of what the scientists needed into information for the architects,” said Greg Cook, managing principal of Holabird & Root.

Holabird & Root faced a few unknowns as they entered the design process in 2015. One of the detectors was overseas, and the other wasn’t built yet. The challenge of designing houses for two detectors, both about a story high but neither of whose dimensions or weight were exactly known at the time, called for some ingenuity.

The architects at Holabird & Root cleverly filled in the blanks for the missing dimensions by designing removable exterior walls and immense exterior doorways.

The removable wall panels of the ICARUS building were designed so that the detector’s sizeable parts will have no problem gliding into the building on their move-in dates.

The SBND building features a floor-to-ceiling bifold door — a door that folds into two parts as it opens — facilitating access for SBND parts. The door folds outward, creating a larger work area inside the building and maximizing doorway space. It is perhaps most impressive feature of the SBND building, its staggering scale resembles that of a docking station for a spacecraft.

During the life of the detectors, these entrances will continue to function as access points for upgrades and new equipment.

The SBN building design also boasts accessory features such as lofty windows that let in bright light. The architects created vibrancy by bringing in carefully selected colors from the official Fermilab color palette onto cranes and electrical work, adding pops of color to an otherwise unadorned interior.

“We need to be respectful of the fact that it’s not just a lab, but a lab where many people work every day, practicing high-energy physics and are proud of the work they do,” Cook said.

The ICARUS detector building brings neutrino physics into its facade, using a pattern of perforations that display a neutrino collision in the aluminum siding. Dixon came up with the idea for the graphic based on an image from a real collision event recorded during ICARUS research in Italy. Engineers at Holabird & Root translated the design into information for a laser cutter, converting the science of the building into an artistic exterior.

“People will continue to work in the buildings for years and years, maintaining the detectors and studying the science,” Cook said.