This year Fermilab celebrates a half-century of groundbreaking accomplishments. In recognition of the lab’s 50th birthday, we will post (in no particular order) a different innovation or discovery from Fermilab’s history every day between April 27 and June 15, the date in 1967 that the lab’s employees first came to work.

The list covers important particle physics measurements, advances in accelerator science, astrophysics discoveries, theoretical physics papers, game-changing computing developments and more. While the list of 50 showcases only a small fraction of the lab’s impressive resume, it nevertheless captures the breadth of the lab’s work over the decades, and it reminds us of the remarkable feats of ingenuity, engineering and technology we are capable of when we work together to do great science.

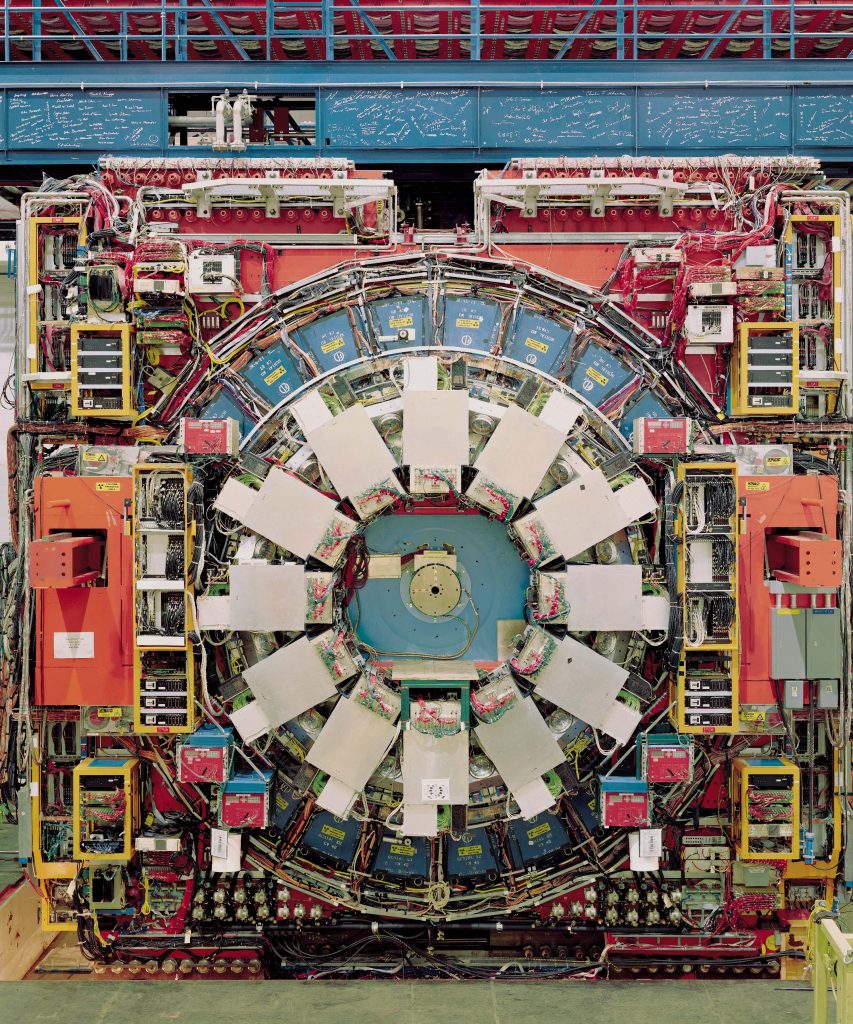

50. CDF and DZero discover top quark

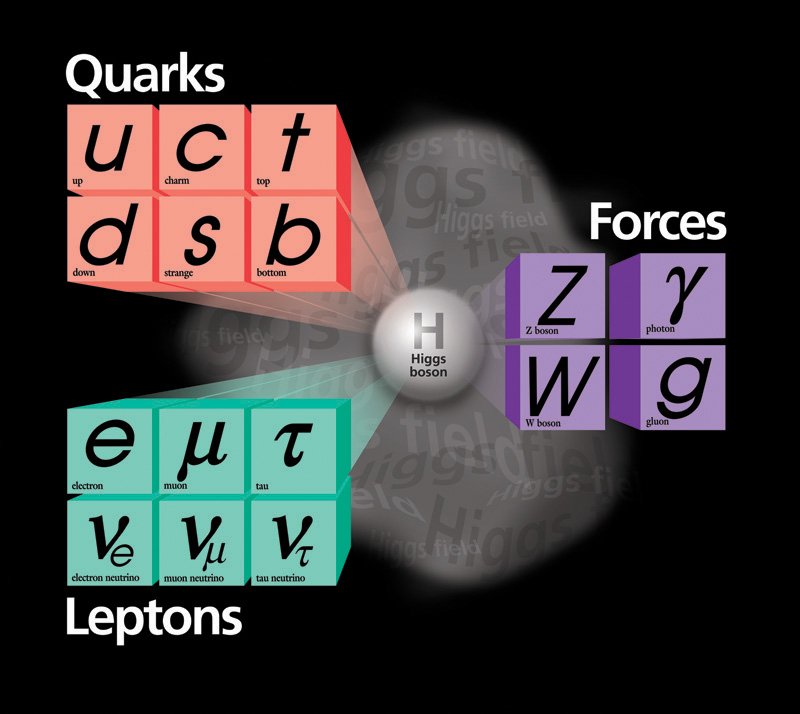

On March 2, 1995, physicists at Fermilab announced the discovery of a subatomic particle called the top quark. It was the last undiscovered particle of the six-member quark family predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics. Scientists worldwide had sought the top quark since the discovery of the bottom quark at Fermilab in 1977. The CDF and DZero experiment collaborations discovered the particle using particle beams from Fermilab’s Tevatron, the world’s highest-energy particle accelerator at the time.

49. Tevatron is the world’s first superconducting particle accelerator

Early accelerators used magnets made of electrical wire wrapped into coils, but those electromagnets lose swaths of energy as heat, driving the electricity bill through the roof. The solution was superconductivity. When cooled to near absolute zero, certain metal alloys allow electric current to flow freely without losing heat. Wound into a coil, they become superconducting magnets, an energy-efficient technology that was already familiar to physicists but never scaled to such a massive endeavor. Alvin Tollestrup was awarded both a National Medial of Technology and the APS Robert R. Wilson Prize for the innovation.

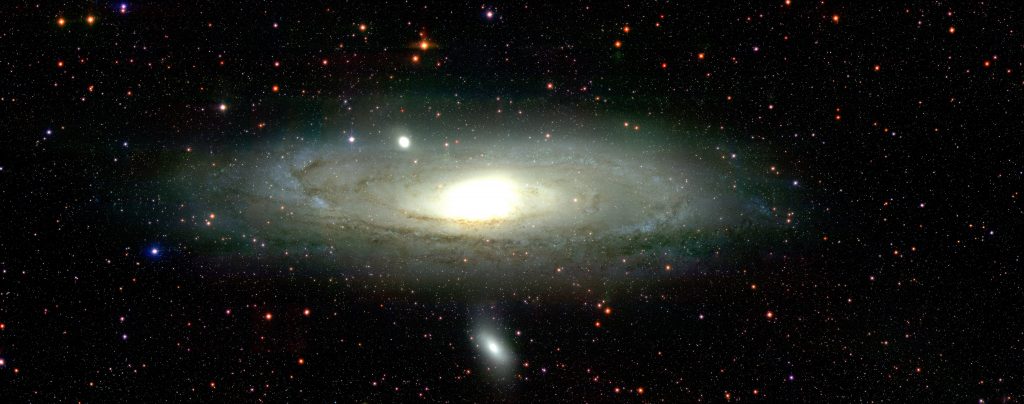

48. Fermilab searches for evidence of dark matter with gamma-rays from the center of our galaxy

Researchers believe that gamma rays — a very energetic form of light — could be produced when hypothetical dark matter particles decay or collide and destroy each other. Fermilab scientist Dan Hooper co-discovered more gamma-rays than he could explain at the center of our own galaxy in 2009 and sparked international interest. Whether dark matter particles or something else is responsible for these gamma rays remains an open and hotly debated question.

47. Bs matter-antimatter oscillations go at 3 trillion times a second

The Standard Model of physics makes some not-so-standard predictions about our universe. Fermilab has pioneered extremely precise technologies that put these theories to the test, including the CDF experiment, which confirmed in 2006 that, yes, a Bs (pronounced “B sub s”) meson actually does switch between matter and antimatter 3 trillion times a second.

46. www.fnal.gov

Particle physics labs were the first pioneers on the World Wide Web. The second web server in the United States belonged to, you guessed it, Fermilab. When it went live in 1992, Fermilab joined a small community that included CERN, SLAC and Nikhef, the Dutch National Institute for Subatomic Physics.

45. Tevatron is the first accelerator to use an electron lens

Fermilab’s Tevatron was the first particle accelerator to make use of an electron lens, a technique that allowed the machine to compensate for destabilizing forces unavoidably generated by the colliding beams. Proposed in 1997, the lenses were installed in 2001 and 2004 in the Tevatron, where they demonstrated beam-beam compensation. They were also used in the removal of unwanted particles. The innovation earned Fermilab scientist Vladimir Shiltsev a European Physical Society Accelerator Prize.

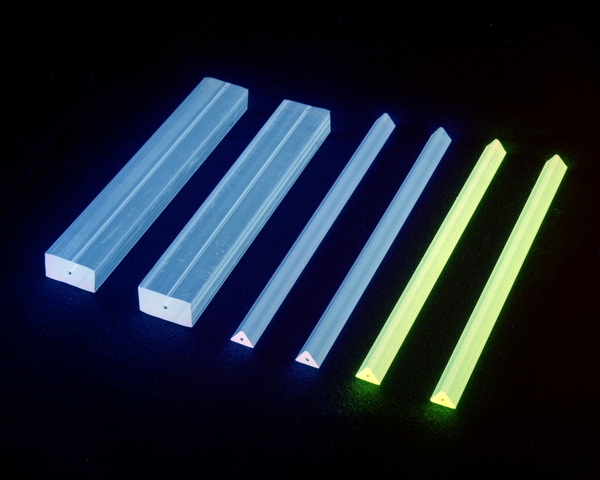

44. Fermilab produces scintillating fiber for large-scale experiments

Fermilab was the first facility to produce plastic scintillating material in fiber form. This plastic scintillating fiber, or SciFi, was first used in a large-scale experiment in 1990. Fermilab later developed an extruded plastic scintillator, which is used in the MINOS detectors. Extruded plastic scintillator is produced exclusively at Fermilab and used in particle detectors worldwide.

43. CDF rounds up the final meson

On March 5, 1998, Fermilab announced it had discovered the Bc meson. This particle was the last of 15 unexcited quark-antiquark pairs to be discovered. The first one had been discovered 50 years earlier in cosmic rays, but this flighty character, which lives just 0.46 picoseconds, could be found only as a product of powerful, high-energy particle collisions.

42. Fermilab develops CCDs for dark matter detection

Fermilab experiment DAMIC shielded a bundle of charge-coupled devices, CCDs, in a copper box, in a copper tube, in lead, deep underground. Any particle that could penetrate the extreme security system would be a top candidate for dark matter. CCD technology, however, was first developed for the Dark Energy Camera. And Fermilab astrophysicist Craig Hogan noted the “delicious irony that these detectors, which are so perfectly adapted for peering to the edge of the universe that we take all the way to Chile for better skies, are now buried in underground caverns to look for invisible particles.”

41. Scientists close in on dark matter using Dark Energy Survey data

Scientists exploring data collected by the Fermilab-constructed, Chilean-based Dark Energy Camera (DECam) discovered 20 satellite galaxies of the Milky Way, nearly doubling the number previously known and adding to those identified by the earlier Sloan Digital Sky Survey, another project where Fermilab played a key role. These tiny satellite galaxies can contain hundreds of times more dark matter than normal matter. Whether the mysterious dark matter turns out to be axions, weakly interacting massive particles or something else, DECam has proven itself to be a powerful new tool for the dark matter community.

40. Fermilab makes the most precise measurement of W boson mass

Fermilab achieved the world’s most precise measurement of the mass of the W boson in 2009 when DZero scientists made the measurement, and then again in 2012 with Fermilab’s CDF experiment. Measuring the W boson, one of the carriers of the weak force, is a messy business. To measure a W boson, researchers at the Tevatron had to measure every decay product of the W boson, which required a detailed understanding of the detectors’ responses to physics beyond the production of W bosons in the collider.

39. Theorists provide comprehensive study of signals and backgrounds in hadron colliders

A collection of contributions made by Fermilab theorists helped the science community understand what the experiments at the world’s two largest colliders — the Tevatron and the LHC — could see. The scientists, including John Campbell, Estia Eichten, Keith Ellis, Walter Giele, Stephen Mrenna and Chris Quigg, produced the first comprehensive study of signals and backgrounds at hadron colliders; created simulation tools that have been used in virtually every Tevatron and LHC analysis; and performed precision calculations of Standard Model processes. These calculations aided the discovery of the top quark at the Tevatron and the Higgs boson at the LHC.

38. CDF makes first use of silicon vertex detectors in a hadron collider environment

In the early 1990s, the CDF collaboration installed the world’s first silicon detector in a hadron collider. Silicon detectors are now a mainstay for tracking short-lived particles very close to the collision point, but for years they were thought too fragile and too difficult to work with for anything besides small-scale experiments. CDF collaborators also developed a hardware system that could use the vast amount of data from the silicon detector in real time to detect displaced vertices, which enabled them to record world-leading-sized samples of beauty hadrons. Fermilab collaborators Aldo Menzione and Luciano Ristori developed CDF’s silicon vertex detector and were awarded the 2009 Panofsky Prize for their work, one of the highest honors a physicist can receive.

37. Fermilab scientists identify sources of beam losses in accelerators

We may think of particles in accelerators as smoothly cruising ahead until they reach their target, but in very high-intensity beams they also destructively interact with each other. James Bjorken and Sekazi Mtingwa, two scientists working at Fermilab, predicted and discovered a number of these “intrabeam scattering” phenomena, which brought about losses and limited the performance of circular accelerators. A related mechanism, called “intrabeam scattering stripping,” was also predicted by theory and experimentally identified by scientist Valery Lebedev as a performance-limiting effect in modern linear accelerators.

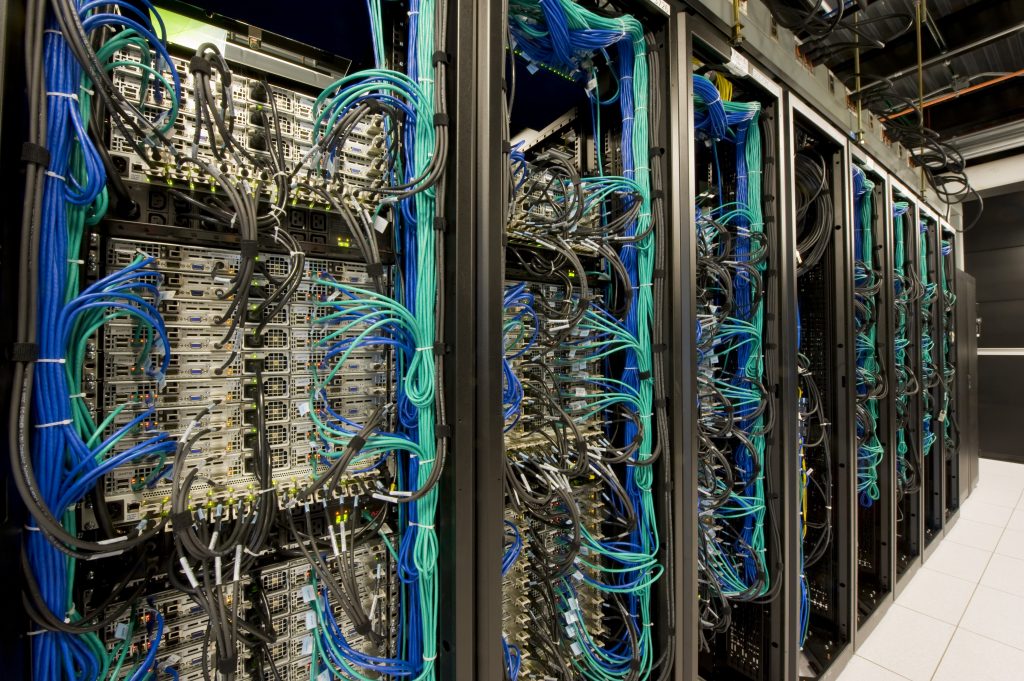

36. Fermilab pioneers the construction of computing farms

Fermilab once possessed the fastest supercomputer in the world. Known as ACPMAPS, (pronounced “A-C-P maps”), the system was installed in 1989 to facilitate deep theoretical explorations into the strong force, one of nature’s four fundamental forces. Soon Fermilab was building more massively parallel computers, pioneering the construction of low-cost computing farms to replace large and expensive specialized systems. With floods of data generated by high-energy physics experiments and mind-bogglingly complex calculations to be carried out in particle physics theory, Fermilab was pushing the bounds of supercomputing.

35. Fermilab constructs long-baseline neutrino experiments

One of the major goals of neutrino physics is understanding the strange phenomenon of neutrino oscillations. This is best done by measuring a neutrino beam in two distant locations. So Fermilab has blazed trails in very long-distance neutrino experiments. The lab set its first distance record at 450 miles when MINOS came online in 2005. Fermilab lengthened its record with the NOvA experiment in 2014, which sets its two detectors apart by 500 miles.

34. Sloan Digital Sky Survey discovers baryon acoustic oscillations

In 2005 the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, of which Fermilab was a major collaborator, confirmed the existence of baryon acoustic oscillations. These BAOs are giant sound waves from the early universe, and their imprint remains on the way matter is distributed today, more than 13 billion years later. Taking measurements of more than 45,000 galaxies, the Sloan survey measured the peaks in these enormous ripples to be roughly 500 million light-years apart.

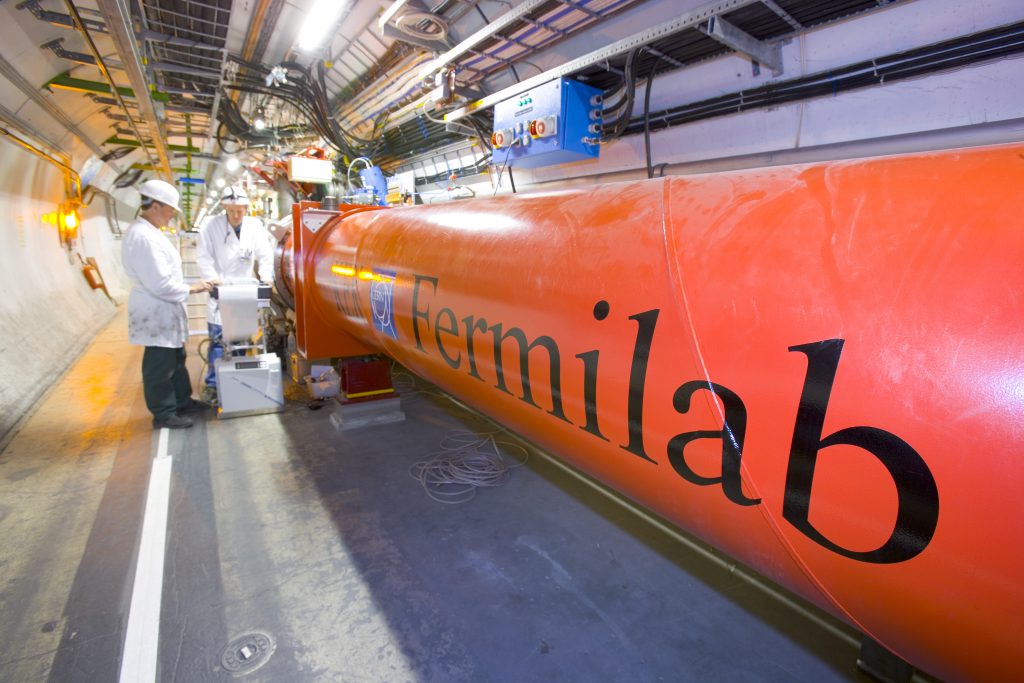

33. Fermilab designs and builds focusing magnets for the LHC

Fermilab designed and built advanced, superconducting magnets to focus particle beams, preparing them for collision, at the Large Hadron Collider. The 43-foot long, 19-ton magnets took a decade to design, develop, manufacture and test, and ultimately became part of the world’s most powerful particle collider.

32. Fermilab advances grid computing

Fermilab has helped develop record-setting computing technologies that foresaw the incredible processing power that would be needed to cope with the data coming from the Large Hadron Collider. These efforts, which include establishing the Open Science Grid, have allowed particle physicists to manage and process enormous amounts of data from global collaborations, while industries such as medicine and finance also benefit from the technology.

31. MINOS and NOvA observe neutrino oscillations

Scientists know relatively little about neutrinos, the most abundant matter particle in the universe. But Fermilab’s MINOS and NOvA experiments have made incredible strides in understanding how and why the fickle particles change their fundamental properties as they travel. MINOS began recording data about the oscillation phenomenon in 2005, and the longer-distance NOvA experiment began in 2015.

30. Fermilab is first to successfully implement slip stacking for accelerating beams

The Fermilab accelerator complex smashes protons into so-called targets to produce other particles that scientists can study. The more protons the accelerator can provide, the more data there is to work with. Fermilab accelerator scientists and engineers were the first to successfully implement a technique called “slip stacking,” which allows the injection of multiple batches of beams into an accelerator at one time. By implementing slip stacking, Fermilab effectively doubled the number of protons delivered by its Main Injector accelerator. Kiyomi Seiya was given an IEEE Particle Accelerator Science and Technology award for the work.

29. Fermilab theorists shine light on paths to new physics

Scientific discovery is something of a guided surprise. You have to know where to look to find something new, but you’re never 100 percent sure it’s there until you see it. Fermilab theorists have been and continue to be guides on the journey to discovery to new physics — physics beyond the reliable Standard Model of particle physics. New paradigms developed at Fermilab have led to extensive theoretical research worldwide. Their ideas have stimulated a multitude of experimental searches: for the Higgs boson and supersymmetry (Marcela Carena), dark matter (Patrick Fox and Roni Harnik), alternative realizations of electroweak symmetry breaking (Chris Hill and Bill Bardeen), and extra dimensions (Bogdan Dobrescu and Joe Lykken).

28. Fermilab measures lifetimes and properties of charm mesons and baryons

Heavy quarks produced in high-energy collisions decay within a tiny fraction of a second, traveling less than a few centimeters from the collision point. To study properties of these particles, Fermilab began using microstrip detectors in the late 1970s. These detectors are made of thin slices of silicon and placed close to the interaction point in order to take advantage of the microstrip’s tremendous position resolution. Over time, Fermilab developed this technology, improving our understanding of silicon’s capabilities and adapting the technology to other detectors, including those at CDF and DZero.

27. Fermilab constructs the world’s first permanent-magnet accelerator

The antiproton Recycler was the world’s first permanent-magnet accelerator. Fermilab’s 8-GeV ring greatly improved the efficiency of antiproton accumulation and cooling, using some 400 permanent magnets. Other accelerators had traditionally used electromagnets, but designers found that using naturally magnetic materials reduced cost and improved stability. This feat was also the result of many technical innovations developed along the way. Bill Foster and Gerry Jackson won an IEEE Particle Accelerator Science and Technology award for the innovation.

26. Fermilab scientists set upper limit for Higgs boson mass

In 1977, theoretical physicists at Fermilab — Ben Lee and Chris Quigg, along with Hank Thacker — published a paper setting an upper limit for the mass of the Higgs boson. This calculation helped guide the design of the Large Hadron Collider by setting the energy scale necessary for it to discover the particle. The Large Hadron Collider turned on in 2008, and in 2012, the LHC’s ATLAS and CMS discovered the long-sought Higgs boson — 35 years after the seminal paper.

25. Fermilab discovers bottom quark

In 1977, an experiment led by physicist and Nobel laureate Leon Lederman at Fermilab provided the first evidence for the existence of the bottom quark. It was observed as part of a quark-antiquark pair known as the Upsilon meson, which is 10 times more massive than a proton. The bottom quark is one of six that make up the quark family of particles.

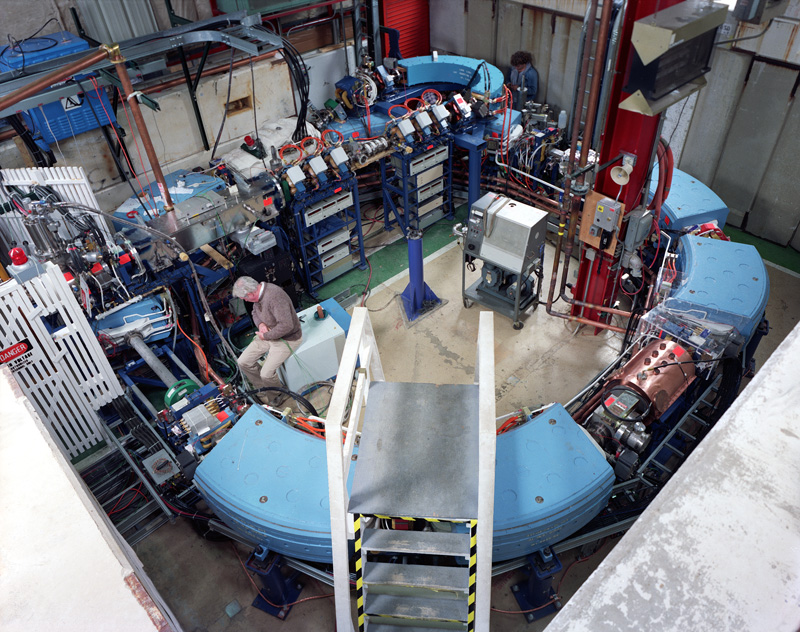

24. Tevatron’s cryogenic system sets benchmark

Upon its commissioning in 1983, the Tevatron’s liquid-helium cooling system was the largest cryogenic system ever built. The system set a benchmark in large-scale superconducting magnet design and has been a model for similar systems worldwide. Its many innovations included advances in gas compression, gas filtering and large-scale system integrity. In 1993, the system was named an International Historic Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

23. Sloan Digital Sky Survey confirms evidence of dark energy

When the universe’s expansion was found to be accelerating in 1998, it seemed to be defying gravity with some unknown force. That force, dark energy, is now thought to make up two thirds of the universe. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a collaboration that includes Fermilab, confirmed its existence. Their analysis of large clusters of galaxies also confirmed the universe’s accelerating expansion.

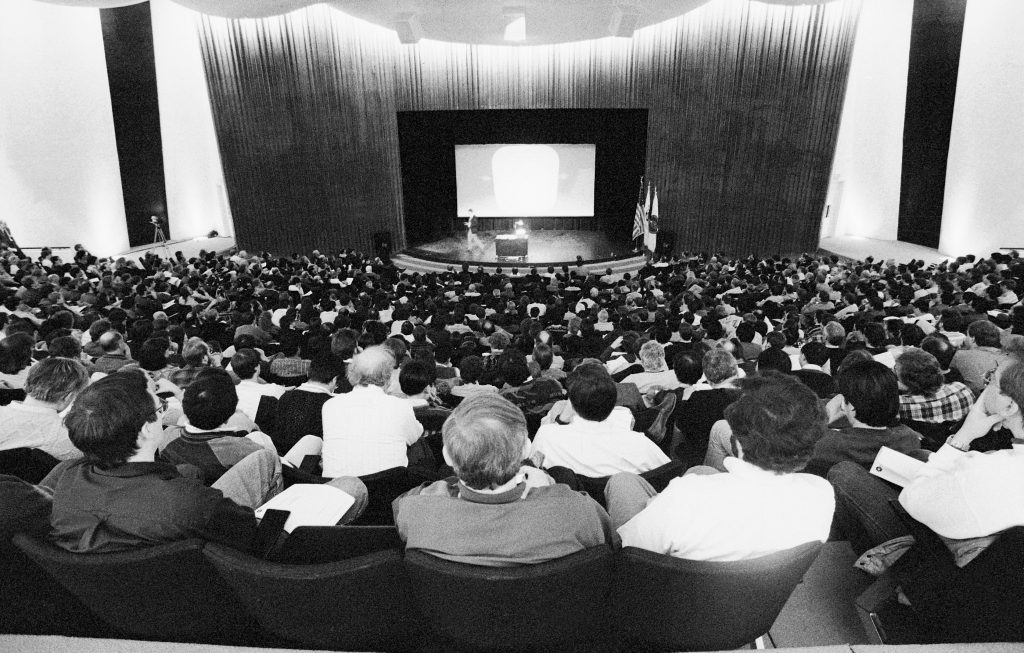

22. Fermilab hosts the first USSR group in a U.S. high-energy physics experiment

When Fermilab began its experimental program in 1972, Cold War tensions were high. Nevertheless, Fermilab extended an olive branch for science. Its first experiment, E-36, was also the first U.S. high-energy physics collaboration with the Soviet Union. It marked the beginning of a long tradition of east-west collaboration at the lab and served as a model of international partnership for the decades to come.

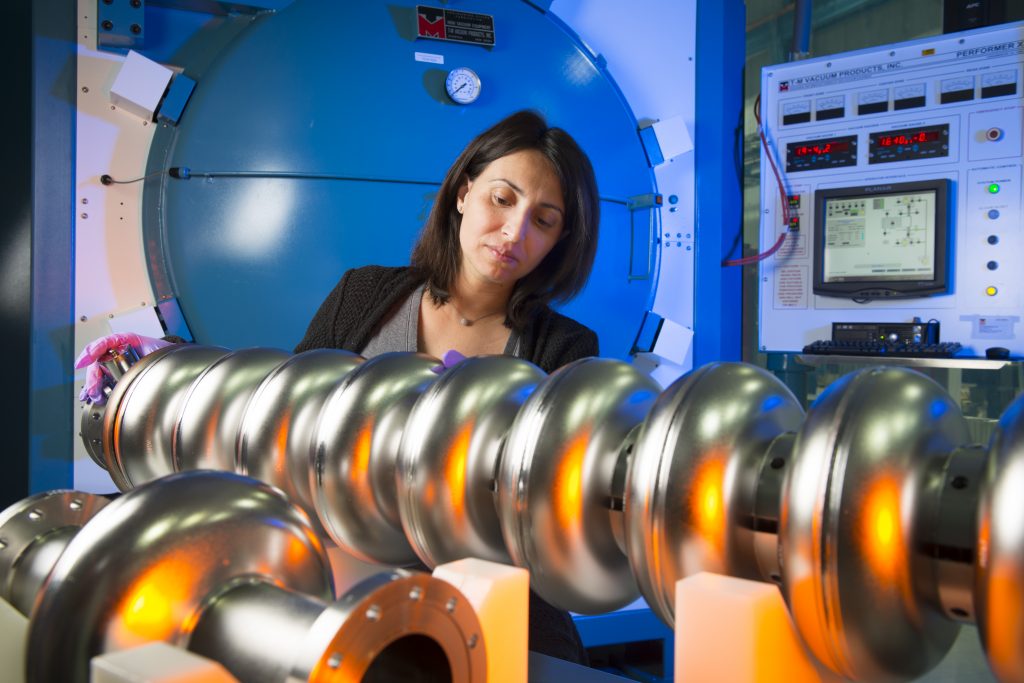

21. Fermilab establishes world-record efficiency for an accelerating cavity

Sometimes it pays to dust off old papers. In 2012, scientist Anna Grassellino began researching superconducting accelerator cavities made of a niobium-nitride alloy, an idea mostly abandoned since the 1990s. Within the year, she had developed the world’s most energy-efficient cavity. The milestone completely changed what people thought about the limits of SRF technology.

20. Fermilab theorists spearhead lattice QCD method for predicting quark properties

Fermilab theorists spearheaded the use of a method that predicted with uncanny accuracy the properties of quarks and the composite objects they form. Fermilab scientists were among the collaborators who, in 2003, demonstrated that the method, called lattice QCD (for lattice quantum chromodynamics), could be carried out with unprecedented precision. What followed was a world-leading program for lattice QCD thanks to advances by Fermilab’s Andreas Kronfeld, Paul Mackenzie, Jim Simone and Ruth van de Water. These calculations, which require high-performance computing facilities, have been indispensable for researchers in all areas.

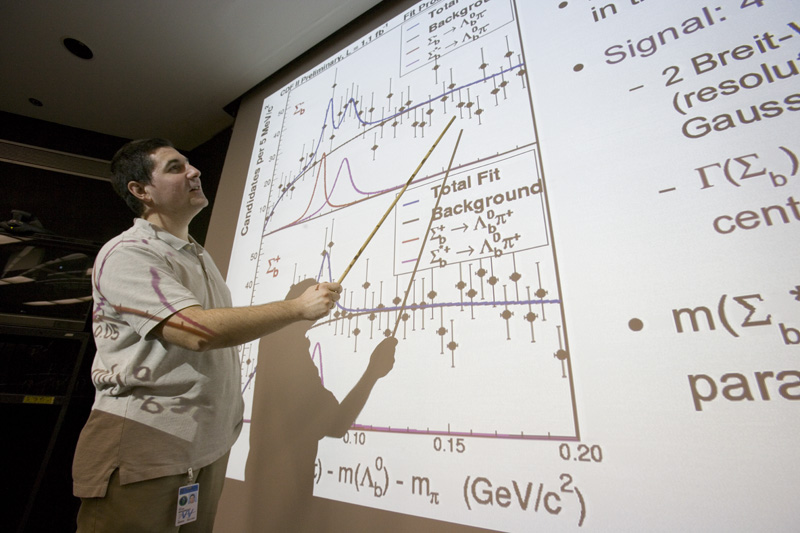

19. Fermilab discovers exotic building blocks of matter

From 1998 to 2011, Fermilab experiments discovered five baryons, particle cousins of the proton, and one more distantly related meson: Ξb0, Σb and Σb*, Ξb–, Ωb– and Bs. These particles were important in our understanding of how matter forms and holds together at the most fundamental level.

18. Fermilab scientists propose dark matter may be made of sterile neutrinos

No one knows what dark matter is, but we’re pretty sure it’s out there: Given their observable mass, the spin rate of galaxies is far too fast. Some other matter — matter we can’t see — must also play a role to cause them to spin with such velocity. Physicists have proposed a number of possibilities for what dark matter is, and Fermilab scientist Scott Dodelson and his colleague Lawrence Widrow were the first to propose that dark matter might be made of sterile neutrinos — hypothetical particles even more weakly interacting than neutrinos. The standard theory of the electroweak force with the addition of sterile neutrinos is one of the simplest ways to accommodate dark matter.

17. That’s quite an antimatter collection you’ve got there

At some 300 billion antiprotons per hour, the Tevatron’s antiproton source was the most intense, consistent source of antiprotons in the world. At this impressive rate, about 17 nanograms of antiprotons were generated at Fermilab over the years, accounting for more than 90 percent of the world’s manmade production of nuclear antimatter. Along with protons, the rare antiparticles were the second half of the Tevatron’s collision equation. The world record for antiproton production made the collider a success.

16. In physics theory, brevity is sometimes the soul of particle physics, too

A (very short!) 1986 paper by Fermilab theorists Stephen Parke and Tomasz Taylor presented an astonishing result: that the result of a very complex Feynman diagram calculation could be summarized in a single line. The full implications of this new mathematical structure are still being explored today in an active area called “amplitudes” research. This leads to both new ways of learning about quantum field theory and practical applications to LHC calculations.

15. Fermilab contributes to Higgs boson discovery

Without the Higgs boson, atoms would not form, and there would be no chemistry, no biology and no life. Its discovery at CERN laboratory was the culmination of nearly five decades of work and included research at Fermilab’s Tevatron accelerator, in particular on the CDF and DZero experiments, and on the CMS experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. Fermilab is the host laboratory for U.S. CMS collaborators. It contributed new ideas and physics models, CMS experiment construction and operation, and computing power and intellectual leadership in data analysis at CMS.

14. Fermilab unveils first proton accelerator for cancer treatment

On Jan. 4, 1989, Fermilab unveiled the first-ever small proton accelerator designed and built expressly for cancer treatment, developed for Loma Linda University Medical Center in California. The room-sized accelerator provided an advanced form of radiation therapy with a beam that could target diseased cells more precisely than traditional x-rays, protecting nearby healthy cells.

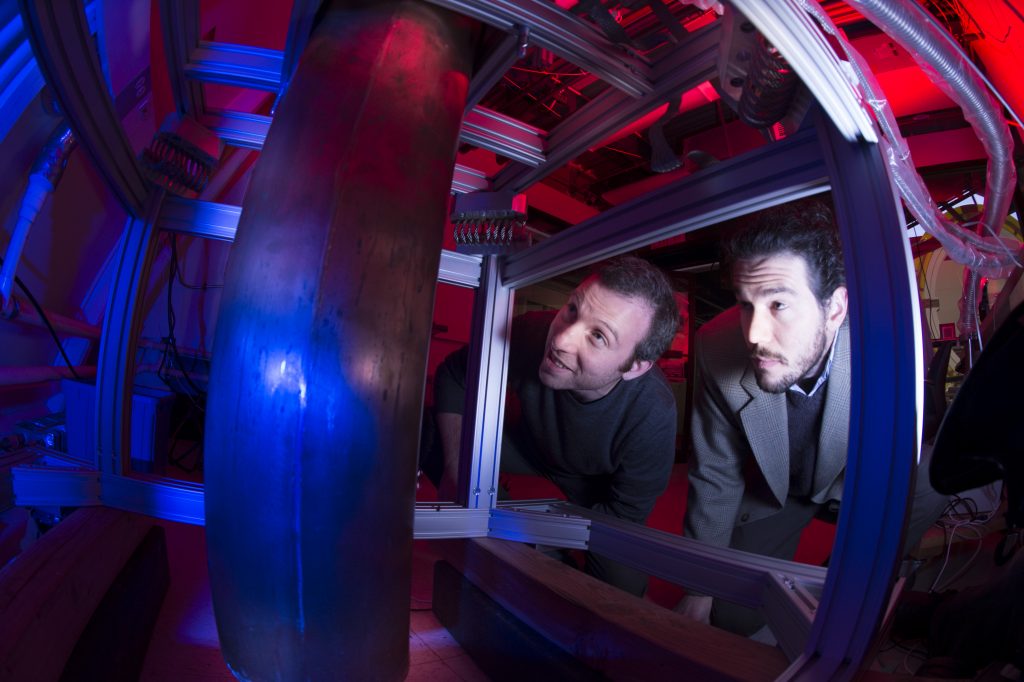

13. Holometer is the first detector for Planck-scale physics

In 2014, Fermilab scientist Craig Hogan’s team began taking measurements with a 40-meter-long instrument they called the Holometer, designed to test a mind-boggling proposition: that the 3-D universe in which we appear to live is no more than a hologram. They built the Holometer to test ideas for ways that space could really be made up of discrete, 2-D pieces that carry information we perceive in three dimensions. This experiment measures reality on the smallest scale we can conceive, where atoms are gigantic compared to the tiny grains of space and time Fermilab researchers are searching for.

12. Observation of direct CP violation in kaon decays

On Feb. 24, 1999, physicists from Fermilab’s KTeV collaboration established the existence of direct CP violation in the decay of kaon particles. The observation was a significant step in understanding why the universe displays an abundance of matter, while antimatter disappeared at an early stage in its evolution.

11. Fermilab scientists are first to invent and apply hollow electron beams in proton colliders

The more tightly the particles are packed into a particle beam, the better chances that the particles will collide in an accelerator. The dynamics of dealing with dense, high-power beams are an enormous challenge. Fermilab scientists were the first to invent, develop and apply what are called “hollow” electron beams to proton colliders. The hollow electron beams enclose a circulating proton beam, cutting down on beam losses that could potentially damage the accelerators and detectors. This halo collimation technique, successfully demonstrated at the Tevatron, is now the technology of choice for current and future particle colliders, including the Large Hadron Collider and the Future Circular Collider.

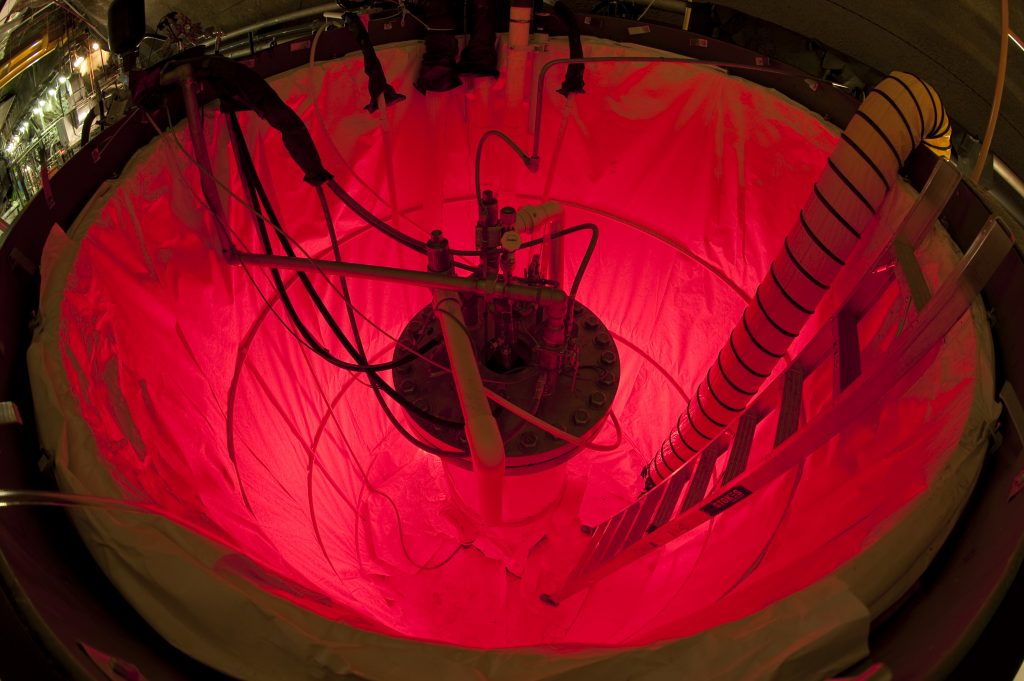

10. COUPP uses bubble chamber technology for dark matter detection

The proud, magnificent, 15-foot bubble chamber that detected particle collisions at Fermilab may have been decommissioned in 1988, but its legacy was rekindled 20 years later when the fundamental concept returned in the search for dark matter. In 2008, Fermilab physicists completed the first run of the COUPP experiment that filled a 1-liter bell jar of superheated liquid, in hopes that dark matter particles would collide with it, theoretically disturbing the liquid and causing it to boil.

9. Fermilab discovers polarization in hyperon production

The 1994 Panofsky Prize, a prestigious award in physics, went to Thomas Devlin and Lee Pondrom, who discovered at Fermilab that, contrary to expectations, certain particle relatives of the proton were polarized when they are produced in collision experiments. This gave the particles properties physicists could measure to better understand the strong force, which glues the particles together and is one of four fundamental forces.

8. Fermilab develops Scientific Linux

Worldwide, both scientists and nonscientists use Scientific Linux, an operating system originally developed for particle physics at Fermilab. The operating system runs on computers at top universities, national laboratories and even in industry.

7. Fermilab is first to scale up electron cooling for antiproton beams

In 2005, Fermilab was the first to scale up a technology known as electron cooling to adapt it for relativistic high-energy antiproton beams. The implementation of the cooling in Fermilab’s Recycler ring by a team led by Sergei Nagaitsev helped increase the rate of particle interactions in the Tevatron collider by a factor of three. Nagaitsev earned a U.S. Particle Accelerator School Prize for Achievement in Accelerator Physics and Technology for the innovation.

6. Fermilab physicist proposes looking for gravitational waves by detecting B-mode polarization

In 1996 Fermilab astrophysicist Albert Stebbins, along with scientists Marc Kamionkowski and Arthur Kosowsky, proposed a way to look for signals of gravitational waves in the cosmic microwave background: by detecting something called B-mode polarization. It would present itself as a distinct pattern in the sky. These very faint signals, “curls” of light from the early universe, could provide evidence of the theory of inflation, which says that the universe underwent a rapid expansion soon after the Big Bang. The BICEP2 experiment later detected B-mode polarization, in 2014, but their signal was likely sourced by astrophysical foregrounds. Upcoming experiments are aiming to detect the primordial signal.

5. Fermilab produces a single top quark

Only one in 20 billion proton-antiproton collisions produces a single top quark instead of much more common pairs. The extremely rare process was discovered at Fermilab in 2009 — 14 years nearly to the day after Fermilab discovered the top quark — and produced some of the world’s most sophisticated data analysis methods in the process.

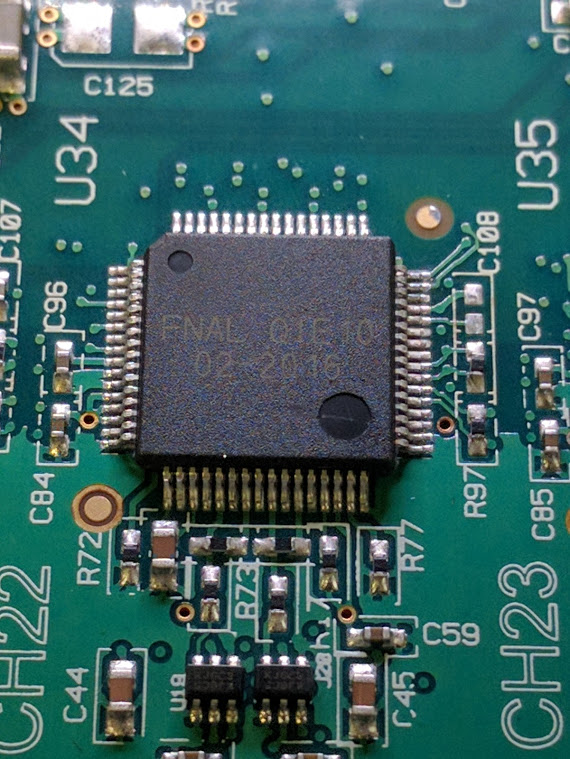

4. Fermilab develops QIE microelectronics for improved data analysis

Transforming the complex signals that detectors produce from particle collisions into digital data requires sophisticated electronics. Performing this task at the heart of many physics labs worldwide, including the CMS detector at the Large Hadron Collider, are devices called QIEs. Smaller than a penny, these integrated circuits, designed and improved upon at Fermilab, combine data from analog signals into a form researchers can analyze with excellent resolution.

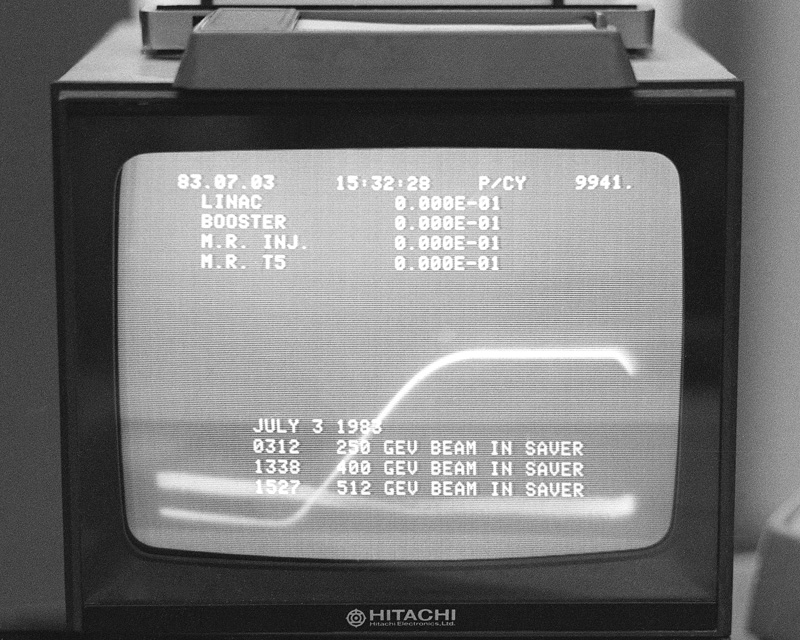

3. Tevatron sets world energy record (again, and again)

At 3:37 p.m. on July 3, 1983, the Tevatron claimed the world energy record by operating its particle beam at 512 GeV. Fermilab held the honor until 2009, beating its own record time and again eventually achieving its namesake energy level, 1 TeV. Scientist Helen Edwards, one of the Tevatron’s architects, was awarded the National Medal of Technology and the APS Robert R. Wilson Prize for her work on the collider.

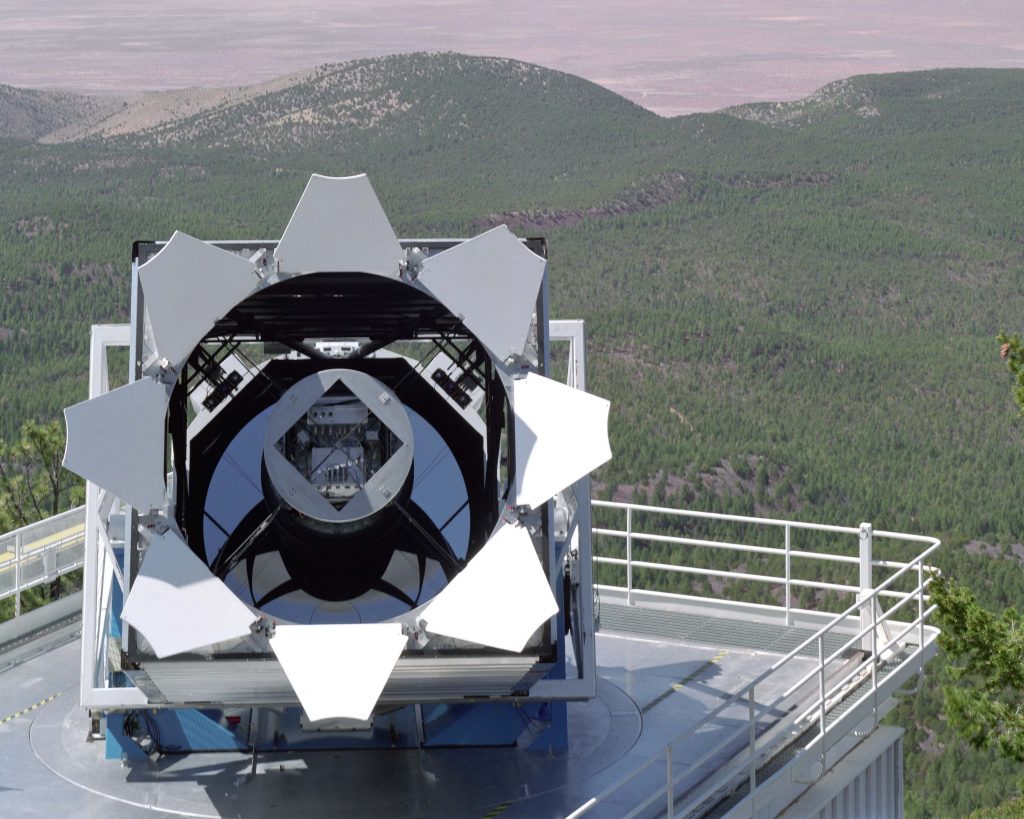

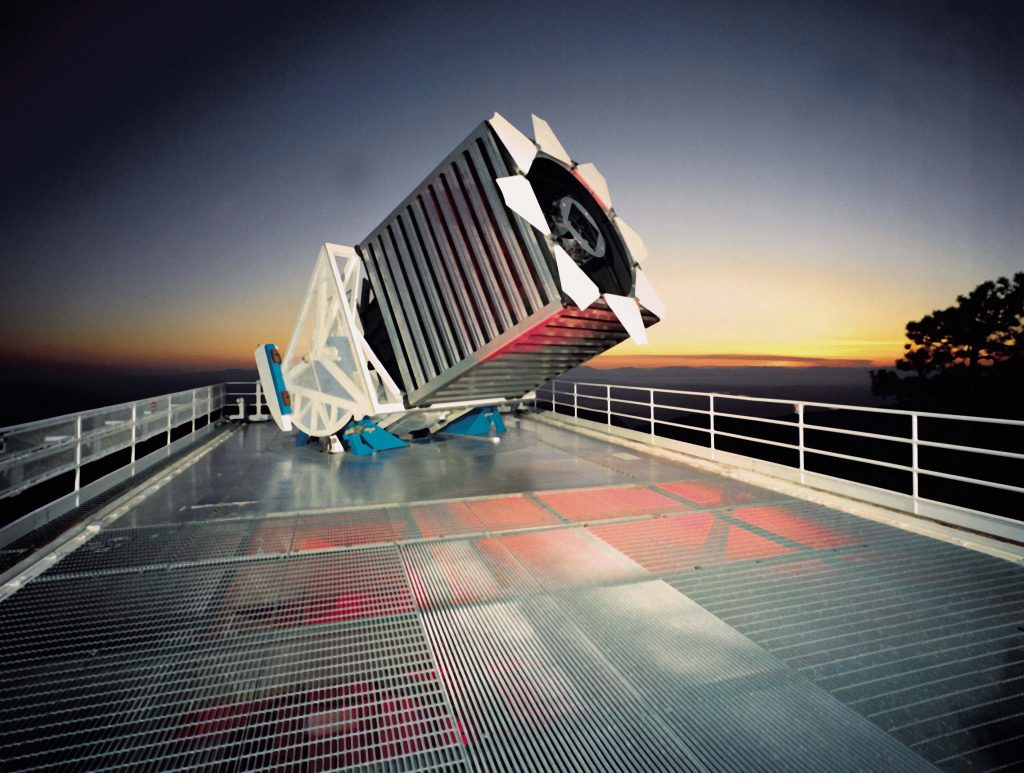

2. Dark Energy Camera opens its modern eye to ancient light

Eight billion years ago, rays of light from distant galaxies began their long journey to Earth. That ancient starlight now finds its way to a mountaintop in Chile, where the Dark Energy Camera, the world’s most powerful camera and mirror system, captured it for the first time on September 12, 2012. That light may hold within it the answer to one of the biggest mysteries in physics – why the expansion of the universe is speeding up. The 570-megapixel Dark Energy Camera was constructed at Fermilab with the partnership of 26 research institutions and more than one hundred companies.

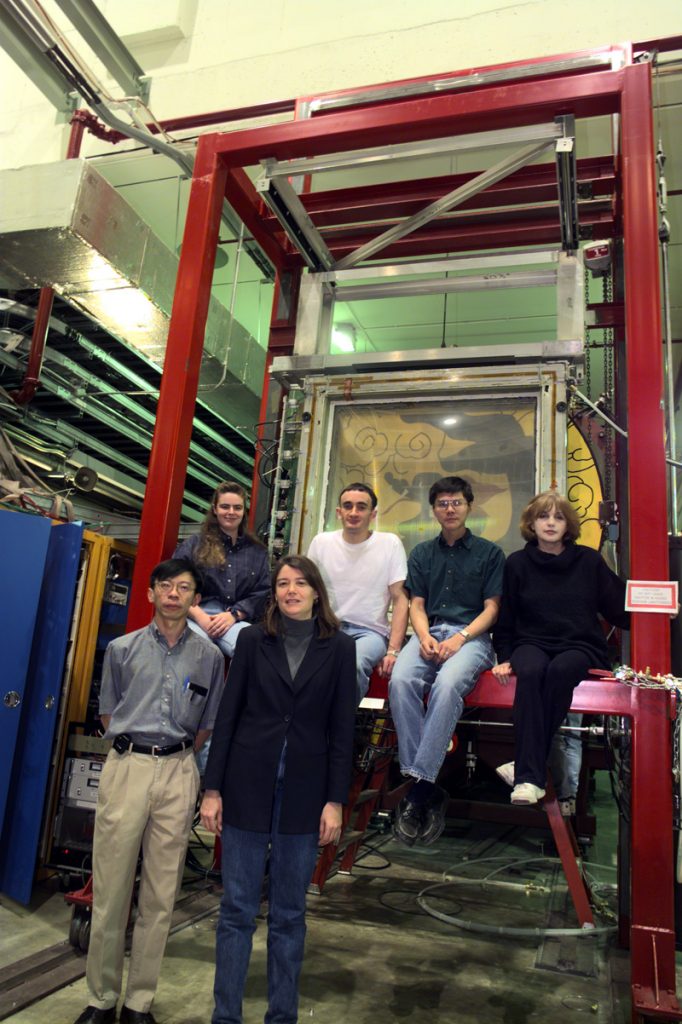

1. Fermilab DONUT experiment discovers tau neutrino

On July 21, 2000, Fermilab announced the first direct evidence for a particle called the tau neutrino, the third kind of neutrino known to particle physicists. It had been hypothesized but never directly observed until the 2000 discovery, which was made by the DONUT (Direct Observation of the Nu Tau) experiment at Fermilab. The other two types, the electron neutrino and the muon neutrino, had been discovered in 1956 and 1962, respectively.

Fermilab founding director Robert Wilson signs the contract with the architectural and engineering company DUSAF in 1967.

In the early 1970s, many of us were working lots of overtime, about 12-hour days. One time, I’d come to work at 6:30 a.m. Thursday morning, worked until 6 or 7 at night, and had just gotten home when I got a phone call: “We need your help.”

It was about DUSAF, the engineering firm that designed the Main Ring, Linac and other conventional facilities.

The DUSAF organization was moving out of their Hinsdale offices, and the mover they’d hired had gone on strike. I was told that DUSAF had to move out by midnight or pay major penalties from the office building they were renting. I was asked if I could grab a vehicle and go to Hinsdale with anybody I could find to help move their stuff out. Others had already been called.

I had a cousin who was working here at the time. I picked him up, and we went to Fermilab and picked up a step van. When we arrived in Hinsdale, a moving van was already loaded, but nobody was doing anything with it. We went into the building where lots of odds and ends were still in the office building. Many people had come to help. It was a madhouse. Everyone just walked in the building, grabbed whatever they could, brought it out, threw it in a truck and drove it to the laboratory. There wasn’t much packing. Whatever you could get in the truck, we moved. I made one trip. Once we got back to Fermilab, I stayed to help sort and unload throughout the night.

We worked all day that Friday, till 5 p.m. We finally got them moved out.

That was probably the most overtime I’d ever gotten in my life.

George Davidson is the head of transportation services at Fermilab.

This is not the liquid-nitrogen tank that Rob and John encountered in that early-1990s lunch time walk. Photo: Reidar Hahn

I think I can tell this now because I’m pretty sure the statute of limitations has expired. Around a year after I joined Fermilab, in the spring of 1992 or 1993, I got into the habit of a lunch time walk on the Ring Road with John Isenhour, who had come here a year or two earlier. John’s job was to manage the library VAX (yes, the library had its own little DEC VAX at fnlib.fnal.gov). In warm weather it was nice to go outside for a few minutes and get a little sun and fresh air.

On one of those days we were just getting started when John saw a big white tanker trailer used for liquid-nitrogen parked next to the A-1 service building on Main Ring Road. It had an open spigot and it was dumping liquid nitrogen on the ground. No one else was around and we had no idea why that was being done, but John put on a pair of gloves he happened to have and found an empty metal coffee can lying on the ground. Holding it under the tank tap by the top edge, he managed to get a quart of liquid nitrogen.

With it boiling away, we walked back into the high-rise. I had some initial misgivings about this, but those evaporated with the nitrogen while we talked of hammering nails with bananas and all the other fun stuff you can do with a very cold liquid. We got on a west side elevator and rode it to the third floor and walked out into the middle of the library, where we proceeded to play around with what was left. By then it was all gone, after only a few minutes, and before we (fortunately) could do much with it.

What mildly amazes me now is how at the time, this seemed like a typical Fermilab thing to do — have fun with unusual states of matter if given the opportunity. I have not been here 50 years, so I can’t be certain about this, but I bet this was the only time a cryogenic liquid was in the Fermilab Library.

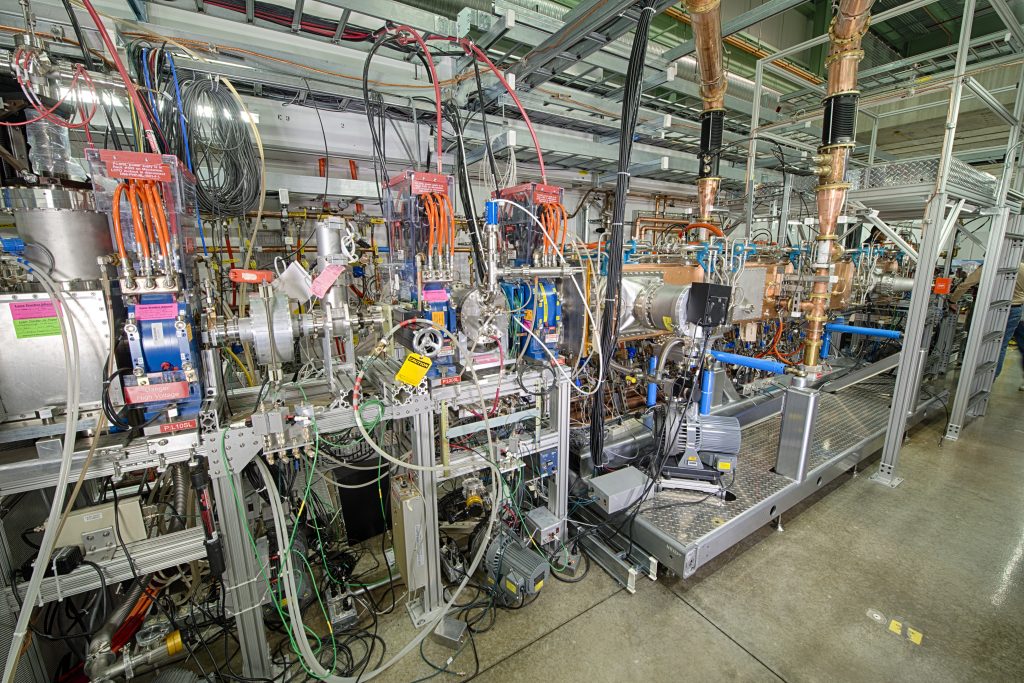

The world’s largest particle hunter of its kind will travel across the ocean from CERN to Fermilab this summer to become an integral part of neutrino research in the United States.

It’s lived in two different countries, and it’s about to make its way to a third. It’s the largest machine of its kind, designed to find extremely elusive particles and tell us more about them. Its pioneering technology is the blueprint for some of the most advanced science experiments in the world. And this summer, it will travel across the Atlantic Ocean to its new home (and its new mission) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

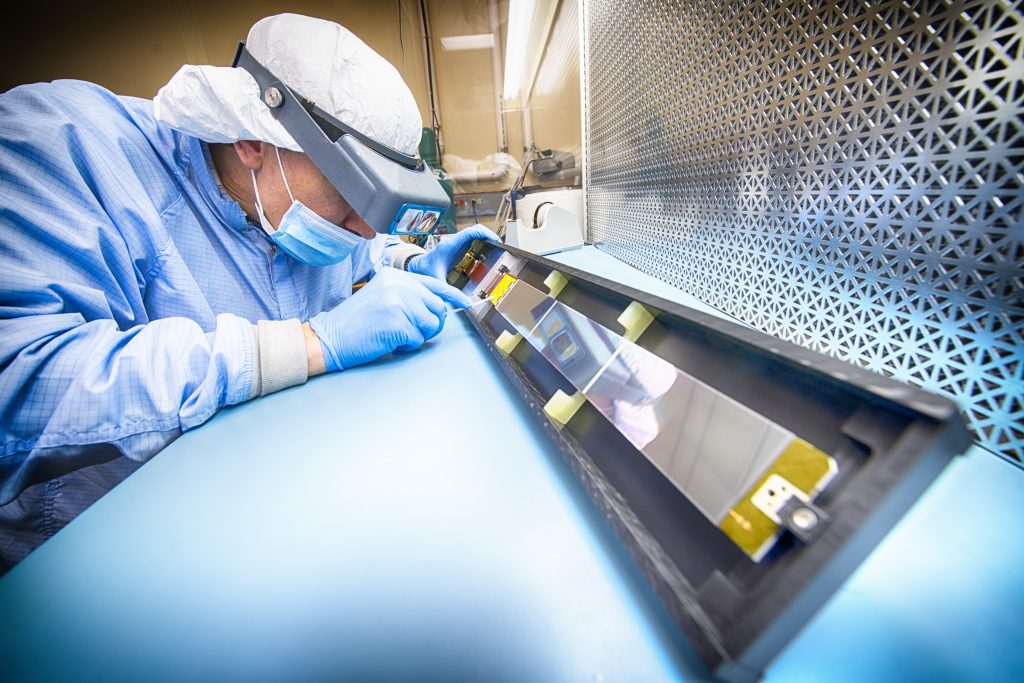

The ICARUS detector, seen here in a cleanroom at CERN, is being prepared for its voyage to Fermilab. Photo: CERN

It’s called ICARUS, and you can follow its journey over land and sea with the help of an interactive map on Fermilab’s website.

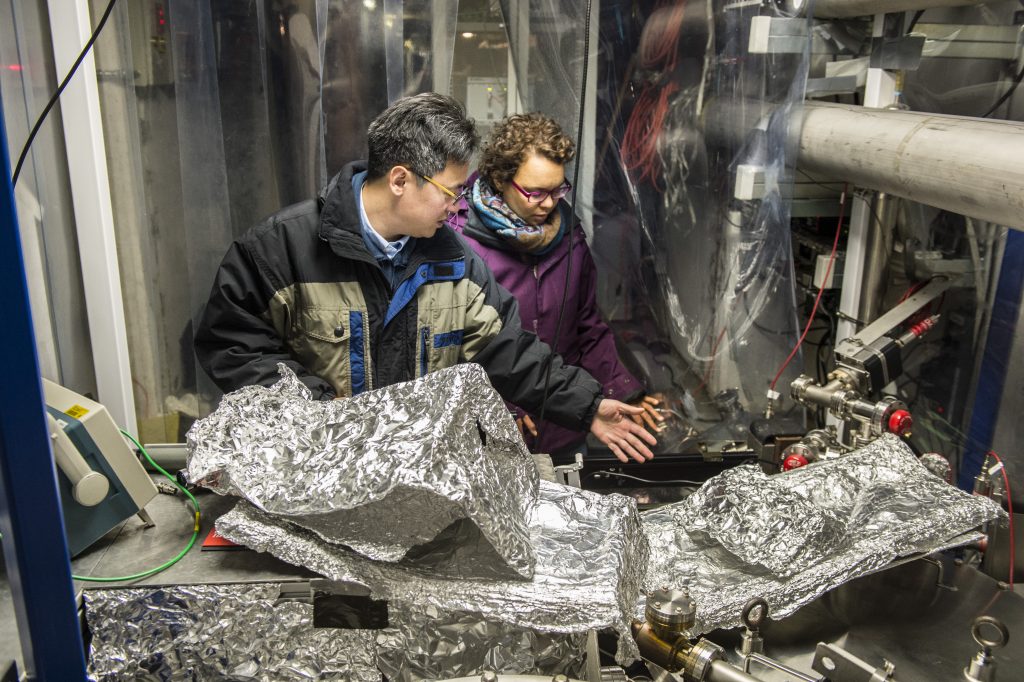

The ICARUS detector measures 18 meters (60 feet) long and weighs 120 tons. It began its scientific life under a mountain at the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics’ (INFN) Gran Sasso National Laboratory in 2010, recording data from a beam of particles called neutrinos sent by CERN, Europe’s premier particle physics laboratory. The detector was shipped to CERN in 2014, where it has been upgraded and refurbished in preparation for its overseas trek.

When it arrives at Fermilab, the massive machine will take its place as part of a suite of three detectors dedicated to searching for a new type of neutrino beyond the three that have been found. Discovering this so-called “sterile” neutrino, should it exist, would rewrite scientists’ picture of the universe and the particles that make it up.

“Nailing down the question of whether sterile neutrinos exist or not is an important scientific goal, and ICARUS will help us achieve that,” said Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer. “But it’s also a significant step in Fermilab’s plan to host a truly international neutrino facility, with the help of our partners around the world.”

First, however, the detector has to get there. Next week it will begin its journey from CERN in Geneva, Switzerland, to a port in Antwerp, Belgium. From there the detector, separated into two identical pieces, will travel on a ship to Burns Harbor, Indiana, in the United States, and from there will be driven by truck to Fermilab, one piece at a time. The full trip is expected to take roughly six weeks.

An interactive map on Fermilab’s website (IcarusTrip.fnal.gov) will track the voyage of the ICARUS detector, and Fermilab, CERN and INFN social media channels will document the trip using the hashtag #IcarusTrip. The detector itself will sport a distinctive banner, and members of the public are encouraged to snap photos of it and post them on social media.

The ICARUS neutrino detector prepares for its trip to Fermilab. Follow #IcarusTrip online! Photo: CERN

Once the ICARUS detector is delivered to Fermilab, it will be installed in a recently completed building and filled with 760 tons of pure liquid argon to start the search for sterile neutrinos.

The ICARUS experiment is a prime example of the international nature of particle physics and the mutually beneficial cooperation that exists between the world’s physics laboratories. The detector uses liquid-argon time projection technology – essentially a method of taking a 3-D snapshot of the particles produced when a neutrino interacts with an argon atom – which was developed by the ICARUS collaboration and now is the technology of choice for the international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), which will be hosted by Fermilab.

“More than 25 years ago, Nobel Prize winner Carlo Rubbia started a visionary effort with the help and resources of INFN to make use of liquid argon as a particle detector, with the visual power of a bubble chamber but with the speed and efficiency of an electronic detector,” said Fernando Ferroni, president of INFN. “A long series of steps demonstrated the power of this technology that has been chosen for the gigantic future experiment DUNE in the U.S., scaling up the 760 tons of argon for ICARUS to 70,000 tons for DUNE. In the meantime, ICARUS will be at the core of an experiment at Fermilab looking for the possible existence of a new type of neutrino. Long life to ICARUS!”

CERN’s contribution to ICARUS, bringing the detector in line with the latest technology, expands the renowned European laboratory’s participation in Fermilab’s neutrino program. It’s the first such program CERN has contributed to in the United States. Fermilab is the hub of U.S. participation in the CMS experiment on CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, and the partnership between the laboratories has never been stronger.

ICARUS will be the largest of three liquid-argon neutrino detectors at Fermilab seeking sterile neutrinos. The smallest, MicroBooNE, is active and has been taking data for more than a year, while the third, the Short-Baseline Neutrino Detector, is under construction. The three detectors should all be operational by 2019, and the three collaborations include scientists from 45 institutions in six countries.

Knowledge gained by operating the suite of three detectors will be important in the development of the DUNE experiment, which will be the largest neutrino experiment ever constructed. The international Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility (LBNF) will deliver an intense beam of neutrinos to DUNE, sending the particles 800 miles through Earth from Fermilab to the large, mile-deep detector at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. DUNE will enable a new era of precision neutrino science and may revolutionize our understanding of these particles and their role in the universe.

Research and development on the experiment is underway, with prototype DUNE detectors under construction at CERN, and construction on LBNF is set to begin in South Dakota this year. A study by Anderson Economic Group, LLC, commissioned by Fermi Research Alliance LLC, which manages the laboratory on behalf of DOE, predicts significant positive impact from the project on economic output and jobs in South Dakota and elsewhere.

This research is supported by the DOE Office of Science, CERN and INFN, in partnership with institutions around the world.

Follow the overseas journey of the ICARUS detector at IcarusTrip.fnal.gov. Follow the social media campaign on Facebook and Twitter using the hashtag #IcarusTrip.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, is one of the world’s leading laboratories for particle physics. The Organization is located on the French-Swiss border, with its headquarters in Geneva. Its Member States are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and United Kingdom. Cyprus and Serbia are Associate Member States in the pre-stage to Membership. India, Pakistan, Turkey and Ukraine are Associate Member States. The European Union, Japan, JINR, the Russian Federation, UNESCO and the United States of America currently have Observer status. Visit CERN’s website at home.cern and follow them on Twitter @CERN.

The Italian Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) manages and supports theoretical and experimental research in the fields of subnuclear, nuclear, astroparticle physics in Italy under the supervision of the Ministry of Education, Universities and Research (MIUR). INFN carries out research activities at four national laboratories, in Catania, Frascati, Legnaro and Gran Sasso and 20 divisions, based at university physics departments in different cities of Italy. Visit INFN’s website at www.infn.it and follow them on Twitter @UffComINFN.