Four institutions from the United Kingdom formalized their participation in the Matter-wave Atomic Gradiometer Interferometric Sensor experiment known as MAGIS-100, under construction at U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. University of Liverpool, Imperial College London, University of Cambridge and University of Oxford signed a cooperative research and development agreement with Fermilab in November.

MAGIS-100 is an innovative, 100-meter-long interferometer experiment. Scientists aim to use cold-atom interferometry to demonstrate quantum superposition of atoms over a distance of a few meters and duration of several seconds. The measurement also will allow scientists to search for signs of ultralight dark matter interacting with ordinary matter. The research will lay the foundation for future gravitational wave detectors. It pioneers technology that could lead to interferometry experiments with baselines of more than 1 kilometer, and thus, greater sensitivity.

“It is exciting to see us expand our long and celebrated partnerships with UK institutions to new scientific domains, with the highly innovative MAGIS-100 experiment,” said Fermilab Director Lia Merminga. “Our UK partners participate in the design, construction and delivery of the detection system for the interferometer, and will also participate in the commissioning and data analysis of the experiment.”

Fermilab Director Lia Merminga and Mark Thomson, executive chair of the Science and Technology Facilities Council, UK Research and Innovation, sign a certificate to commemorate the international cooperative research and development agreement that fortifies R&D and experimental activities among Fermilab and U.K. institutions for the MAGIS-100 experiment. Also attending the ceremony were DOE Office of High Energy Physics Associate Director, Gina Rameika; Kyle Dolan, attaché from the British Embassy; representatives from the signing universities, Fermilab and the MAGIS-100 collaboration; and additional representatives from DOE. Photo: Ryan Postel, Fermilab

Mark Thomson, Executive Chair of Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), which is the primary UK funder of MAGIS-100, said, “This initiative is an exciting opportunity, both for the U.K. and the U.S., to collaborate in new technologies for fundamental science. There is huge potential in applying quantum technologies to our scientific mission to uncover the secrets of the universe.”

MAGIS-100 will be vertically mounted in a 100-meter-deep access shaft built for a neutrino experiment at Fermilab many years ago. Scientists will cool strontium atoms to close to absolute zero temperature and drop them down a vacuum tube. Laser beam pulses traveling between mirrors at the opposing ends of the vacuum tube will hit the strontium atoms. This will cause the atoms, acting like tiny atomic clocks, to simultaneously move at two different velocities and exist at two different states. Scientists will measure and compare signals to look for the superposition of two quantum states, pushing the boundaries of how far an atom can be driven apart from itself. They’ll also look for deviations that could be caused by ultralight dark-matter particles interacting with the atoms.

MAGIS-100 is part of Fermilab’s quantum science initiative. Universities working on the Atom Interferometer Observatory and Network, also known as AION, a flagship U.K. project that aims to use cold-atom interferometry for fundamental science, have been involved in MAGIS-100 from the beginning. AION collaborators are working with Stanford and Northwestern universities to develop several optics components for the experiment. They are providing the cameras that will record interference patterns of fluorescent light emitted by strontium atom clouds hit by laser light. They are also fabricating critical optical components, needed for the experiment’s mirror systems, and working on the data acquisition system.

Individuals from eight organizations participated in-person or remotely in a ceremony at Fermilab for the signing of the international cooperative research and development agreement between Fermilab and U.K. institutions: British Consulate, UK Research and Innovation, Fermilab, Imperial College London, Stanford University, U.S. Department of Energy, University of Cambridge and University of Oxford. Photo: Ryan Postel, Fermilab

Fermilab’s MAGIS-100 collaborators, with their know-how and experience in planning, constructing and running large-scale experiments, are working with AION collaborators to scale up cold-atom interferometry, which started as small, university-based experiments.

“What is special about this collaboration is how we are working together. We are expanding Fermilab’s expertise in working with cold atoms while bringing cold-atom interferometry into a large-scale experiment,” said Robert Plunkett, Fermilab’s project scientist for MAGIS-100.

In addition to the UKRI funding, the MAGIS-100 project is also supported by a $9.8 million grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and funds from the DOE Office of Science’s Office of High Energy Physics through the QuantISED program,

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Wilson Hall, the iconic building that serves as the heart of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory’s Batavia campus, is now open to the public.

Visitors are welcome to experience the science exhibits on the atrium level and eat in the café, visit the Ramsey Auditorium, the second-floor art gallery and the ground floor credit union. The art gallery may be closed at times due to special events taking place. All of these areas will be open Monday through Friday from 7:00 am to 5:00 pm.

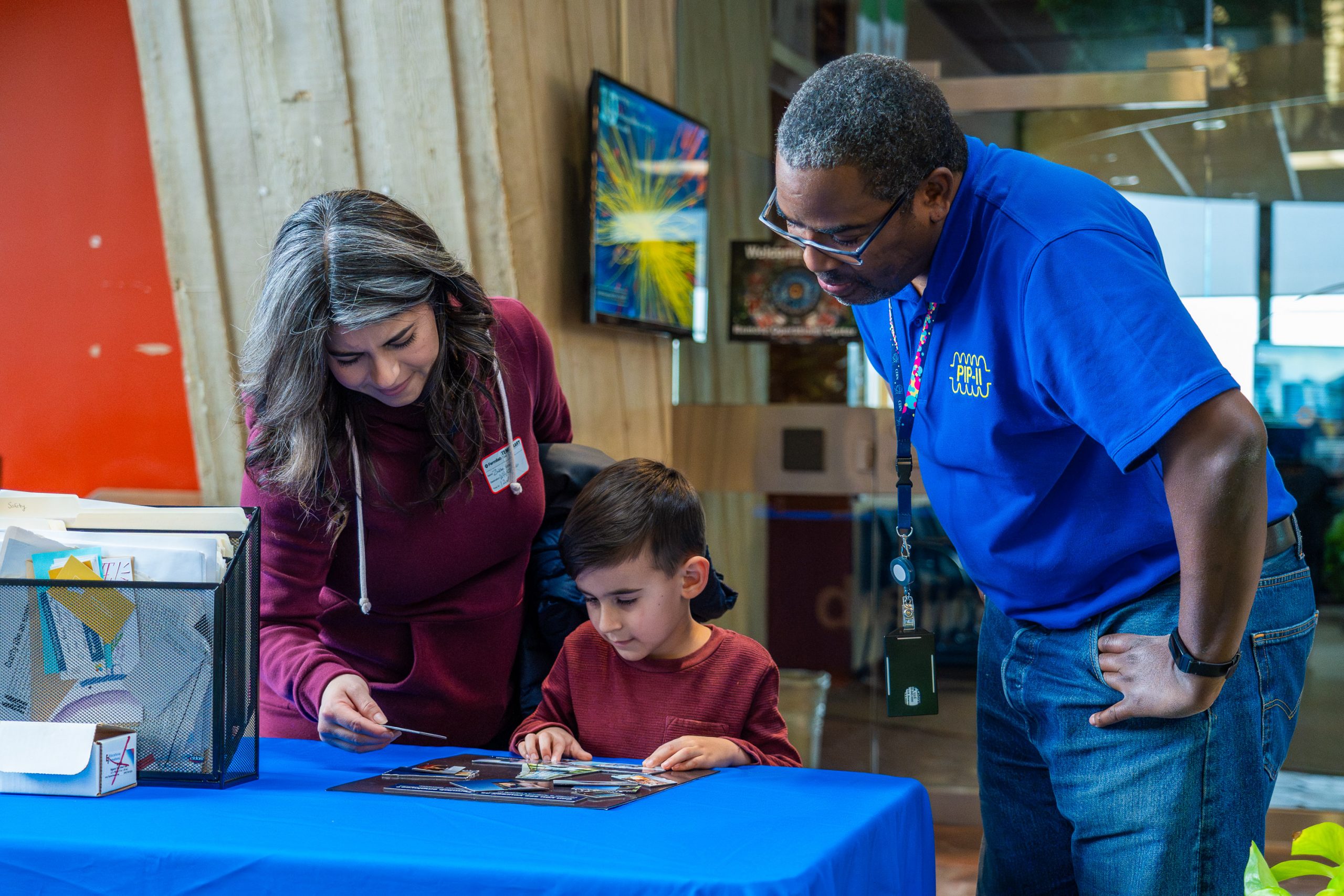

Fermilab’s iconic Wilson Hall is open to the public Monday through Friday from 7:00 am to 5:00 pm. Photo: Daniel Svoboda, Fermilab

For those wishing for a guided tour of the lab, Fermilab has begun hosting monthly public tours on the 3rd Monday of each month starting on Feb. 19th. To sign up please register here.

The spring 2024 Saturday Morning Physics program for high school students begins Jan. 27 with a live driving tour. The program runs every Saturday through April 13. Registration is still open and required.

The Lederman Science Center continues to be open to the public Monday through Friday 9:00 am – 5:00 pm and Saturdays from 9:00 am – 3:00 pm.

REAL ID-compliant identification is required for all visitors to enter the site, which provides visitors with access to Wilson Hall, the Lederman Science Center, walking trails, and the bison herd for viewing.

When visiting Wilson Hall parking is available on the west side of the building. Please check the Covid Community Levels before visiting for any requirements.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Public message from the Fermilab director on Fermilab access

Dear colleagues and friends of Fermilab,

Throughout our history, Fermilab has had a tradition of being open and welcoming to staff, users, the scientific community and neighbors. However, we know that for some members of our community, this tradition has not been upheld over the past few years. My team and I vowed to do better. After all, Fermilab must foster a culture of openness and collaboration in order to keep leading the country — and the world — in particle physics research, education and outreach.

I am pleased to share a significant step forward in these efforts. Today, Jan. 23, 2024, Fermilab is reopening our iconic Wilson Hall to the public.

As of today, any member of the public who enters the site with proper identification has access to portions of Wilson Hall: the atrium and café on the main floor, Ramsey auditorium for public conferences, the credit union on the ground floor, and the Fermilab Art Gallery on the second floor.

This is a development many months in the making, and I appreciate your patience as my team and I worked diligently to make this happen. I am deeply appreciative of the DOE Headquarters and Fermilab Site Office for their partnership with us that made this possible and the Site Access Steering Committee for their ongoing work to ensure the lab is open and accessible to the community, users and affiliates.

As of Jan. 23, 2024, any member of the public who enters the site with proper identification has access to portions of Wilson Hall: the atrium and café on the main floor, Ramsey auditorium for public conferences, the credit union on the ground floor, and the Fermilab Art Gallery on the second floor. Credit: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

Additional recent developments

Since my last letter in May 2023, we have made solid progress in improving site access. In October, a review of Fermilab site access controls and requirements was conducted by peer labs, and a Site Access Steering Committee was established to work with teams across the lab to ensure cross-functional collaboration in determining the vision for the site access end state, objectives, goals, and action steps needed to achieve the vision, and the accompanying communications for each milestone achieved.

We also opened the Aspen East Welcome and Access Center to provide a location for our team to help collaborators and business visitors complete the badging process. And in November 2023, we benchmarked site access policies and procedures against other comparable DOE laboratories and restarted public tours, more of which will come in 2024.

Access to additional buildings was enabled for all badged employees, users and affiliates. The buildings included in this first phase were IERC, IARC, ICB and FCC. More buildings, including SiDET, will come in future phases. An online single-form access request became available, streamlining the access request process for our collaborators, visitors, and guests. And we have established robust communications with employees and stakeholders to gather input and keep people informed.

As we have done for over a year, Fermilab is pleased to continue to welcome onto the Fermilab campus public visitors showing proper identification for site access. The Batavia and Warrenville gates are open for walkers, bikers, dog walkers, and visitors to enjoy the campus, visit our bison, tour the science experiments and displays in the Lederman Science Center, hike our restored prairie trails, and now, visit the Wilson Hall atrium, art gallery and credit union. Saturday Morning Physics with live tours and other STEM activities returned to the Ramsey Auditorium in early 2023.

In the 2023 calendar year, we are proud to have welcomed over 19,000 people to Fermilab’s site, including 11,000 business visitors, 4,000 users and 2,000 contractors. Separately, over 5,500 public visitors came on site to enjoy our science exhibits, nature trails and bison.

Please check the website for the lab’s current site access requirements.

Progressing toward the future

As outlined in my previous letter, Fermilab is a federal institution and is therefore required to implement federal regulations and U.S. Department of Energy requirements that have been established for all DOE National Laboratories. These requirements have shifted in the last decade and in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Like similar labs, we believe we should strive to provide a welcoming environment for our scientific and community partners while ensuring safe and secure operations.

While we have made progress toward these objectives, the job is not complete. We are still working on several of our goals, including further streamlining the access request form and approval processes, and defining our desired future state with a project plan. We still intend to provide regular reporting on site access metrics and trends as well as the project plan’s progress via email and messages to collaborators and neighbors.

We are deeply committed to our culture of openness, and we are also deeply committed to the safety of our employees, subcontractors, users, affiliates, visitors, and neighbors and to the security and stewardship of the world-class facilities, infrastructure and data at the lab.

I continue to thank you for expressing your views, concerns and opinions with me. The dedication and passion shown by our employees and community members demonstrates how seamlessly integrated Fermilab is as an institution, and it is extremely valuable and appreciated.

With best regards,

Lia Merminga

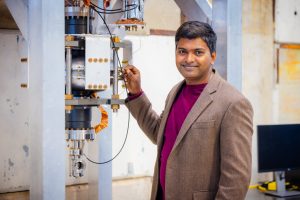

Particle accelerators have many uses in industrial settings. To advance a new type of compact particle accelerator, the U.S. Department of Energy has awarded funding to Charles Thangaraj, a senior scientist at the DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. He and his colleagues are developing devices called cathodes that will generate electrons to be propelled with Fermilab superconducting radio frequency technologies.

The $100,000 award by DOE’s Office of Technology Transitions and the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management will continue the work done by Thangaraj and Daniel Bowring during their participation in the third cohort of the DOE Office of Technology Transition’s Energy I-Corps program. The Energy I-Corps program trains national lab researchers to evaluate industry needs and potential market applications for their technologies.

”DOE’s Energy I-Corps program offers Fermilab researchers the opportunity to explore the potential of technologies we develop for particle physics to be applied to other applications,” said Cherri Schmidt, the manager of Fermilab’s Office of Partnerships and Technology Transfer who pioneered the Energy I-Corps teams at Fermilab. “With this additional funding, we can research and develop one of the key components of our compact SRF accelerator—the electron source—and take the next step toward commercial applications.”

Thangaraj and the team at the Illinois Accelerator Research Center, known as IARC, aim to combine small-scale cryogenic and superconducting technologies in the development of compact accelerator prototypes. It will make compact accelerators more efficient and feasible than current state-of-the-art compact accelerators.

“I am thrilled to receive this award from DOE OTT and FECM, which will allow us to take the next step in the commercialization of our work at Fermilab in compact accelerators,” said Thangaraj, who is a senior technology development and commercialization manager at Fermilab.

“We are bringing together some of the most cutting-edge technologies to radically simplify the cooling infrastructure in our machines, which makes it attractive for commercial applications,” said Thangaraj. “There is always a challenge whenever you try something innovative, but that is also where the opportunities and fun are.”

Charles Thangaraj stands next to a superconducting cavity that will accelerate electrons in a compact accelerator. Photo: Tom Nicol, Fermilab

Compact accelerators for industry

The compact accelerators under development at Fermilab are about the size of a conference room table and capable of delivering high-energy electron beams, up to 10 million electron volts, and high power up to 1 megawatt.

“Based on our market research and conversations with industry, we know there is a demand for machines that can deliver beams of high-energy electrons for a variety of applications,” said Chris Edwards, engineering project manager at Fermilab.

One such use case is metal 3D printing, which involves laying down metal powder and fusing the added metal with an electron beam. Refractory metals, such as tungsten, tantalum and niobium, are resistant to heat and wear. They hold significant manufacturing value in the energy and aerospace industries.

The same properties that allow refractory metals to perform under harsh conditions create significant barriers to metal 3D printing. Fermilab’s compact SRF accelerator technology shows promise to overcome these obstacles.

“Compact accelerators are extremely versatile. Even though we are currently focusing on a few specific applications, these machines can have a far wider range of uses,” said Edwards.

Along with metal 3D printing, Fermilab scientists are also developing compact accelerators to treat and reinforce asphalt for roads.

By incorporating molecular chains into asphalt mixtures and blasting the asphalt with a beam of electrons, construction companies could make roads and infrastructure more durable.

This setup would involve placing a compact accelerator on the back of a truck. The compact accelerator would launch beams of electrons downward toward the asphalt.

“We feel it is crucial that we leverage the power of technology to spur economic growth, foster community development and create an environment of innovation. The IARC team, OPTT and Fermilab management are encouraged by the DOE support and commitment to these endeavors,” said William Pellico, IARC director.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

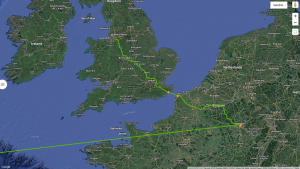

A highly technical and delicate piece of equipment weighing 27,500 pounds, or 12,500 kilograms, just made a whirlwind transatlantic trip in its custom transportation frame.

The fully equipped prototype of a cryomodule is one of the many components that will be part of the new linear particle accelerator at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The successful shipment was an important transportation test and part of Fermilab’s Proton Improvement Plan II project, PIP-II, which receives contributions from several international partners, including the United Kingdom.

The PIP-II project team is constructing a 215-meter-long, state-of-the-art superconducting particle accelerator to upgrade Fermilab’s accelerator complex. At 10 meters long, the HB650 is the largest cryomodule needed for the new accelerator. Four modules will make up the last section of the new machine. When complete, the PIP-II accelerator will produce the world’s most powerful neutrino beam for the international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, hosted by Fermilab.

Members of the PIP-II team from Fermilab and STFC UKRI stand in front of the prototype HB650 cryomodule at Daresbury Laboratory. Credit: STFC

Neutrinos are the most abundant matter particles in the universe. By sending neutrinos from Fermilab, close to Chicago, to the huge detectors of DUNE in Lead, South Dakota, physicists can study the particles’ mysterious behavior and search for answers to the universe’s biggest questions.

PIP-II will receive components from partner institutions in France, India, Italy, Poland and the United Kingdom. Fermilab will receive three assembled cryomodules — known as HB650 for the radio frequency they use to operate — from their partners at the Science and Technology Facilities Council in the U.K. and ten similar ones from partners at Commissariat à l’Énergie Atomique et aux Énergies Alternatives, or CEA, in France.

To ensure that all three cryomodules make it safely from STFC’s Daresbury Laboratory near Liverpool to Fermilab, the PIP-II team is conducting extensive tests of the transportation system. Shipping the prototype cryomodule from Fermilab to the U.K. and back was the final test before shipping the first actual cryomodule built in the U.K. to the United States.

In 2022, the collaboration assembled a special transportation frame, designed to fit the HB650 cryomodule, at Fermilab. STFC led the frame’s development with assistance from PIP-II collaborators at Fermilab and CEA in France.

The prototype HB650 cryomodule, wrapped in plastic, is lowered into its custom transport frame after being inspected at Daresbury Laboratory. Credit: Jeremiah Holzbauer, Fermilab

The PIP-II team then performed a successful transportation test with the frame and concrete blocks with the dimensions, weight and mounting points of the actual cryomodule.

PIP-II staff completed the prototype HB650 cryomodule at Fermilab in early 2023. It includes three superconducting radio-frequency cavities for particle acceleration made by partners at the Raja Ramanna Centre for Advanced Technology, provided as in-kind contributions from India.

The first of its kind in the world, the cryomodule underwent months of testing before the PIP-II team loaded it into the transportation frame for its trip to the U.K. and back. It departed Fermilab on Nov. 27. The cryomodule flew on a cargo plane to Luxembourg and then rode on a truck to Daresbury Laboratory, where it was tested. It returned to Fermilab along the same route and arrived on Dec. 14.

The PIP-II team tracked the prototype cryomodule with a GPS device as it traveled from Fermilab to Daresbury Laboratory in the United Kingdom. This map shows the European leg of its journey. Credit: Adam Wixson, Fermilab

The successful completion of this test is the final demonstration that the many challenging aspects of transporting cryomodules are well understood. This includes logistics, customs, handling, instrumentation and, especially, the detailed design of the many delicate components in the cryomodule.

“Our partners require that we manage the risks of this equipment transportation,” said Jeremiah Holzbauer, PIP-II scientist and former transportation manager. “This successful transport of a real cryomodule to and from a partner institution is the proof that we can execute what the project needs. We encountered and overcame many challenges during our tests. In the end, the prototype cryomodule shipment went basically flawlessly — and that’s because we were well prepared.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Researchers are collaborating across the world to encode information using quantum science to perform powerful calculations and distribute information across networks.

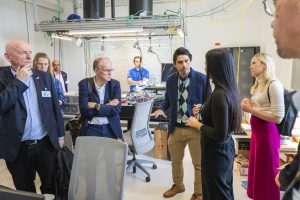

On Nov. 15, a delegation of researchers from the United Kingdom visited the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory to see firsthand the lab’s efforts to advance quantum information science.

The U.K. and the U.S. are no strangers when it comes to collaborating on quantum research. In 2021, a joint statement between the U.S. and U.K. set the stage for the two countries to team up to tackle some of the biggest challenges in quantum information science.

The delegation represented researchers from across the British government, industry and academia who conduct research in quantum science and technology. They met with Fermilab’s leadership team and discussed opportunities to collaborate on quantum networks.

A delegation of researchers from the U.K visited Fermilab in November. At the Quantum Network Lab, they learned how Fermilab can send entangled quantum information to partner labs across Illinois. From left: Gerald Buller, Heriot Watt University; Richard Penty, University of Cambridge; Cristian Peña, Fermilab; Carmen Palacios-Berraquero, NuQuantum; Caroline France, Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. Photo: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

Panagiotis Spentzouris, associate lab director for the Emerging Technologies Directorate, provided a detailed overview of the lab’s work on quantum networks.

Fermilab is the lead institution on the Illinois-Express Quantum Network. The guests had a firsthand glance of Fermilab’s Quantum Network Lab, one of two IEQNET nodes provided by Fermilab. The network distributes entangled quantum information through fiber-optic cables between Fermilab and Argonne National Laboratory, as well as between the Chicago campus of Northwestern University and the Evanston campus of NU. With this network, researchers are laying the foundation for a quantum internet. In particular, they can test different quantum systems that connect to this network.

The U.K. delegation met with Fermilab leadership to talk about becoming further involved in research on quantum networks. The delegation included representatives from the British Consulate; BT Group; Department for Science, Innovation and Technology; Heriot Watt University; Innovate UK; National Physical Laboratory; NuQuantum; Toshiba Europe; University of Cambridge; University of Oxford; and University of York. Photo: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

The delegation also toured laboratory spaces of the Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center at Fermilab. It is one of five DOE national quantum information science research centers signed into existence through the 2018 National Quantum Initiative Act. Two U.K. institutions, Royal Holloway University and the National Physical Laboratory, were invited to join the SQMS Center’s 30 partner institutions earlier this year. Cooperative research and development agreements are now being established to enable these important new partnerships.

After touring the recently inaugurated SQMS quantum garage, the guests concluded their visit with a closeout session with Fermilab’s leadership team.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.