Brian Vaughn examines the output directional coupler for a PIP-II solid state amplifier. Photo: Ryan Postel, Fermilab

How long have you worked at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory?

I’ve been working at Fermilab just under two years, and I’ve been moving around a lot. I have a hand in PIP-II and some Booster upgrade efforts for the PIP-II injection energies. I’m also working on an effort to make a Main Injector superconducting cavity, which is very fun, because it’s very hard, and no one’s ever been able to do it. I don’t know if I can, but I’m trying.

Of the projects you’re working on, which is your favorite?

I would say the most fun I’ve had is with that Main Injector superconducting cavity, just because I’ve had to learn so much in such a small amount of time. I learn by doing: I can’t necessarily just read something and retain it; I have to apply it over and over before it starts making sense to me. I’ve been learning so much about superconducting properties and all the challenges that go with making cavities [that can store an extraordinary amount of energy with very little power loss].

I think I’ve gotten a lot more skills that are readily applicable to all the things that we do, so I would say that’s been the most rewarding project thus far.

What’s the biggest challenge to making a superconducting cavity for the Main Injector?

The biggest challenge is that superconductivity requires a very specific set of conditions to be maintained at all times, like low temperatures for example. There are tunable superconducting cavities out there, but they don’t have a wide enough tuning bandwidth to be able to handle what the Main Injector needs. So right now, we have to use normal conducting cavities to handle that bandwidth and tuning speed. I’m trying to fix that.

[It’s] going to be a big challenge, but if we can figure it out, we’ll be able to reduce the number of cavities needed to accelerate the beam by an order of magnitude, which is extremely beneficial for high-intensity beam stability. Having many cavities places a pretty hard limit on your beam intensity because the cavities act back on the beam. Reducing the number of cavities by the projected amount makes that limit go away, which would be a game-changer for machines all over the world.

Is there anything about working at Fermilab that you particularly enjoy?

If you’d told me five years ago I’d be working on particle accelerators, I never would have believed it because I just thought that it was so far outside of my purview. But it really isn’t. I have so many skills that are applicable to all these things. I’m super glad about that because in my previous jobs, I was just doing the same thing over and over again. There, I didn’t get to work at the edge of my competence, which is why I got a Ph.D.

Here, I’m pushed in so many different directions at once. Usually, that sounds like a bad thing, but I get to expand in ways that I don’t imagine I’d be able to do in many other places. I’m very grateful for that.

Who are some of the role models you’ve had in your life?

My AP Physics teacher in high school. His name was John Taska. He made the class so very engaging. At that point, I kind of knew that I wanted to do something STEM-ish, but I didn’t have my field nailed down quite yet. He made the electrical engineering portion of the class one of the most fun I ever had in any class in high school, and I was like, “I need to be this guy. I need to do what this guy did,” because it was just so compelling. It clicked for me. So, I’m very, very grateful for Mr. Taska, for illuminating that pathway for me.

And Katherine Johnson — she’s my biggest role model in the sphere of Black historical figures. She was subjected to social obstacles that were immensely more pervasive than I can imagine. There’s still a ways to go, but things then were not where they are now. I’ve been afforded massive amounts of help and opportunities that she did not receive, and yet, look at what she accomplished. She was just as responsible for [putting] the first American in orbit and then the lunar landing and everything after that as anyone else at NASA. Her genius, her grit and her perseverance and grace are awe-inspiring. If she could do that with the obstacles that she was faced with, I can try my best.

What do you like to do outside of the lab?

I’m an amateur martial artist, and I like engaging with that physicality.

I also like watching documentaries about NASA a lot. The space shuttle is my favorite engineering project ever: I have a poster of the space shuttle in my office; it’s my Zoom profile picture; I love that thing so terribly much. I went to the Houston Space Center recently while attending the United States Particle Accelerator School. I cried twice; I’m not ashamed. Just engaging with engineering marvels and space type stuff, I love doing that.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

On Dec. 10, 2022, the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics was bestowed upon Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser and Anton Zeilinger at a ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden. The prestigious award recognized scientific achievements in quantum physics “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science.”

The Nobel-winning research directly applies to quantum efforts at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Specifically, experiments done by Zeilinger have contributed to the development of technology behind the Illinois‐Express Quantum Network, or IEQNET, led by Fermilab.

A joint research project among Fermilab, Argonne National Laboratory, Northwestern University and Caltech, IEQNET is a metropolitan-scale quantum network testbed that uses deployed optical fiber and other currently available technology. It is one step toward developing a quantum internet — a network in which information is delivered over long distances with qubits, the units of information for quantum computers and networks.

IEQNET uses a combination of cutting-edge quantum and classical technologies to transmit quantum information. Researchers also designed it to coexist with classical networks. The design and implementation of IEQNET are outlined in a scientific paper recently published in IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering.

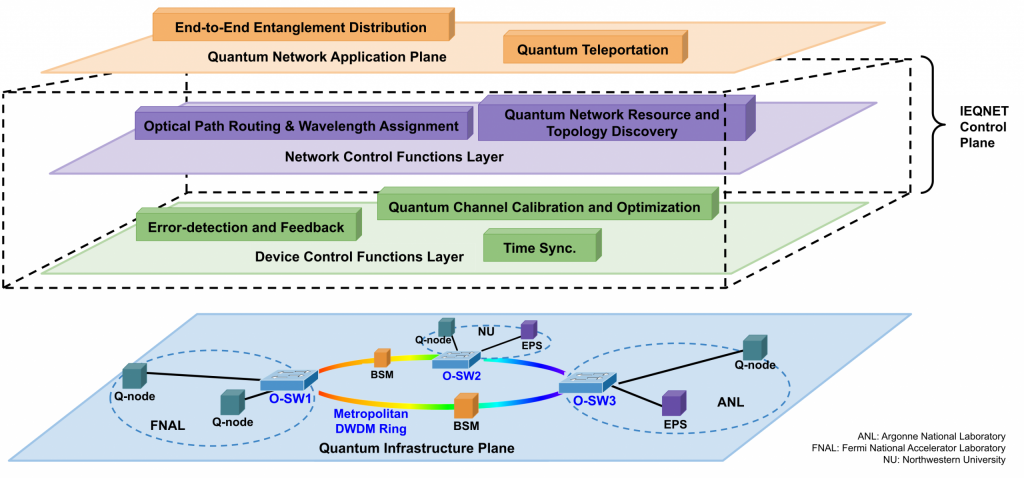

IEQNET’s quantum networking architecture relies on three planes: an infrastructure plane (connectivity of physical devices), a control plane (control of individual devices and the network as a whole), and an application plane (end-to-end networking services). Image: IEQNET

“With the design, we are describing the control functions that will automate the operation of IEQNET,” said Joaquin Chung, a research scientist in the Data Science and Learning Division at Argonne National Laboratory.

“At IEQNET, we want to develop an automated system that can make those connections without a human making the changes,” said Chung. “So things work like a production system and not like a tabletop experiment.”

The paper also explains some of the experiments that IEQNET collaborators have conducted. The results inform what needs to be built into the architecture of the network.

Chung said the paper is important because it aims to bridge the gap between physicists focused on demonstrating nascent technologies and theorists who are thinking 20 years into the future.

“With the resources we have now, can we build a system that works autonomously — and thus improves upon physics experiment and approaches what is envisioned in theory papers? That’s the importance of this engineering paper that lays out the design of IEQNET,” said Chung.

Quantum teleportation and entanglement swapping

For more than five years, IEQNET researchers and collaborators have developed and deployed quantum systems that generate and distribute entangled photons over already-existing telecommunications optical fiber.

To protect and facilitate the transfer of quantum information over a quantum network, IEQNET will use technology enabled by Nobel laureate Anton Zeilinger’s research. “We are standing on the shoulders of these Nobel winners,” said Chung.

In quantum teleportation, a quantumly entangled photon pair shared between two locations is used to transfer a qubit quantum state between them. Demonstrated by Zeilinger in a 1997 experiment, it is a way to transfer quantum information from one system to another without physically transferring the original qubit that encodes the information. This provides a means to protect the quantum information from loss during the transfer process. It is especially important because arbitrary unknown quantum states cannot be copied, due to the no-cloning theorem in quantum mechanics. So, copying the state is not available to protect from loss. In addition, it allows for extremely secure communication; if the information were intercepted or manipulated by an attacker, the entanglement would break, and the sender would know immediately.

“We’re establishing a high-tech attractor in the Chicagoland area. We want to help create the Silicon Prairie for quantum technologies and microelectronics in the Midwest.” – Panagiotis Spentzouris, principal investigator of IEQNET

Importantly, said Christoph Simon, who did his doctoral work with Anton Zeilinger at the University of Vienna, Zeilinger’s experiments opened the door to multi-photon entanglement — as opposed to two-photon entanglement — which is crucial for quantum networks.

“You had to somehow overlap photons from different sources, from different pairs. That was the key conceptual and technological step they had to take,” said Simon, now a professor at the University of Calgary. “Once you can do entanglement of three or four photons, you can scale it up, and now people can do dozens.”

Zeilinger also demonstrated entanglement swapping, the entanglement of two separate photons that never came in contact with each other. This type of entanglement will be essential for developing quantum repeaters, technology key to enabling long-distance quantum communication that is not yet feasible. IEQNET is currently a repeaterless network, which works at the metropolitan scale; demonstrating entanglement swapping is the collaboration’s next goal.

“The Silicon Prairie for quantum”

IEQNET consists of multiple sites geographically dispersed across the Chicagoland area, and each site has one or more quantum nodes. These “Q-nodes” generate or measure quantum signals, such as entangled photons, and communicate the measurement results via standard and classical signals and conventional networking processes.

The architecture of IEQNET, as described in the IEEE paper, uses software-defined networking technology to perform traditional wavelength routing and assignment between the Q-nodes. Its structure facilitates a network, rather than a series of links. It’s analogous to having a multi-way conference call in which any two parties can talk at any given time and still be understood as opposed to a simple two-person phone call.

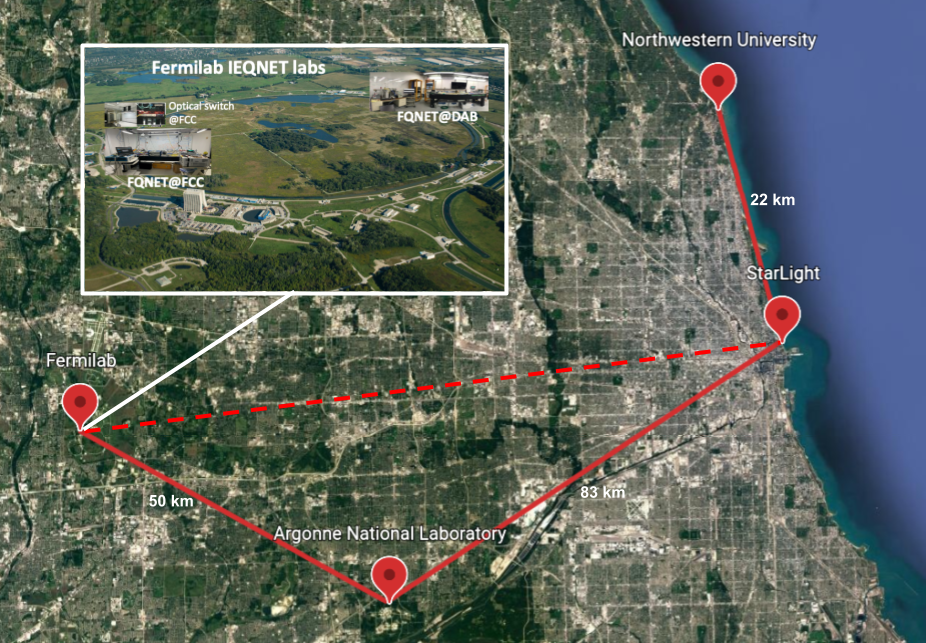

With Q-nodes at Fermilab, Argonne and Northwestern University’s Evanston campus and the proposed node at Northwestern’s downtown-Chicago campus, the metropolitan Chicago area is well poised to become a quantum hub.

IEQNET employs classical networking technology and transparent optical switches to implement network functions, such as establishing lightpaths — a lightpath is a path between two nodes in the network in which light passes through unmodified — between quantum nodes via routing and approaches used in transparent optical networks. IEQNET deploys transparent optical switches at Fermilab, Argonne and StarLight, an internet exchange point on Northwestern’s Chicago campus. Quantum nodes are deployed at all three locations; Fermilab has multiple nodes at two locations separated by ~2.5 km. A fiber optical connection about 150 kilometers long runs from Fermilab to Argonne to StarLight and to Northwestern’s Evanston campus. An additional connection has been requested between the Fermilab and StarLight locations. Image: IEQNET

“We’re establishing a high-tech attractor in the Chicagoland area,” said Panagiotis Spentzouris, head of the quantum science program at the Fermilab Quantum Institute and principal investigator of IEQNET. “We want to help create the Silicon Prairie for quantum technologies and microelectronics in the Midwest.”

IEQNET collaborators have already demonstrated record teleportation fidelity at Caltech and at the Fermilab IEQNET quantum nodes. In June 2022, IEQNET achieved record synchronization between nodes at Fermilab and Argonne, with quantum and classical signals co-propagating. This “co-existence” of quantum and classical signals — also demonstrated in 2021 for polarization entangled photons, the kind used in Zeilinger’s groundbreaking work, between Northwestern’s Evanston and Chicago campuses — is essential for the deployment of a functional quantum network.

A fiber optical connection about 150 kilometers long already runs from Fermilab to Argonne to an internet exchange point called Starlight on Northwestern’s Chicago campus to Northwestern’s Evanston campus.

“The fiber links interconnecting the sites of IEQNET are rightsized for the currently available quantum hardware. As quantum technology matures, and new hardware becomes available, the IEQNET architecture and control functions are designed to accommodate the new hardware,” said Prem Kumar, professor of information technology at the McCormick School of Engineering at Northwestern. “Therefore, we anticipate a rapid progression of advances in quantum networking.”

IEQNET’s ultimate goal is to implement the architecture design and test it using these metro-scale links.

“We’re using well-established and developed Fermilab competencies that we have acquired because of our excellence in our high-energy physics program — that is, the controls engineering, system integration, architecture — things that we know how to do because of who we are,” said Spentzouris. “We are applying that know-how to new emerging fields, such as quantum networks, that will have tremendous implications on the well-being of people and the advancement of other fields outside of high-energy physics.”

The Illinois‐Express Quantum Network is supported by Advanced Scientific Computing Researchin the DOE Office of Science.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.