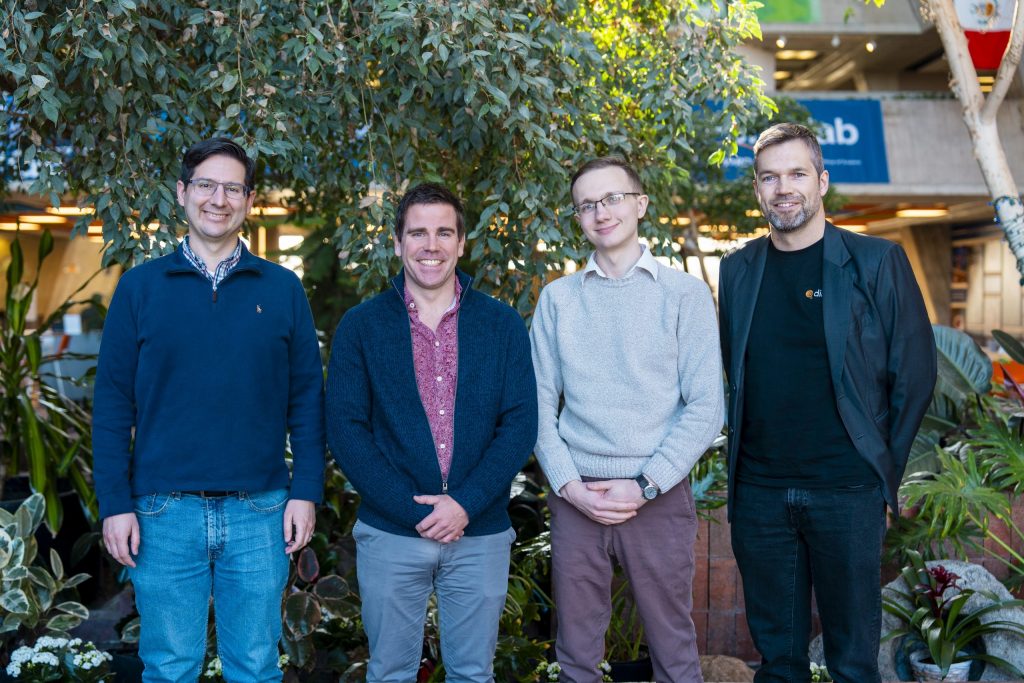

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, along with scientists and engineers at the computer chip manufacturer Diraq, University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of Chicago and Manchester University, have proposed the development of a quantum sensor made of quantum bits called spin qubits in silicon to probe beyond Standard Model physics. Diraq is a global leader in quantum computing technology on silicon, which is essential to the Quandarum project.

By placing many spin qubits together on a chip to form a sensor, the researchers seek to enable scientists to tease out even the faintest signals from the cosmos. Such a sensor could potentially be used to detect axions, hypothetical particles that some scientists believe comprise dark matter.

Led by Fermilab, the Quandarum project is one of 25 projects funded for a total of $71 million by the DOE program Quantum Information Science Enabled Discovery. The QuantISED program supports innovative research at national laboratories and universities that applies quantum technologies to use for fundamental science discovery.

With this award, researchers plan to develop a novel sensor, bringing together for the first time two specialized technologies: spin qubits in silicon and cryogenic “skipper” analog-to-digital converter circuits used for the readout of dark matter detectors.

Silicon spin-based quantum sensors can provide a powerful platform for testing theories around dark matter because they can exploit quantum interactions to increase sensitivity and explore the limits of what scientists understand about high-energy physics.

It’s all about the spin

Spin qubits store information in the direction of an electron’s spin, a property defined by quantum mechanics. The spin state of an electron is very sensitive to weak electromagnetic fields in the environment, allowing for extremely precise measurements.

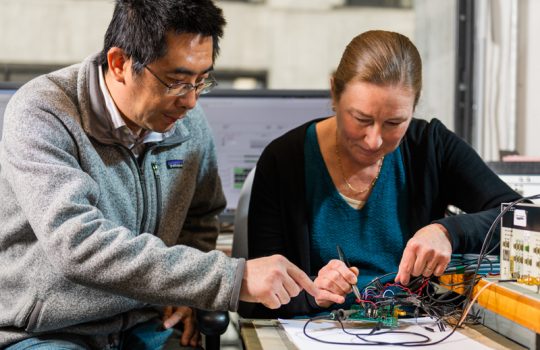

“We can’t directly measure what the direction of the spin is, but we can measure small movements of charge because moving charge creates a change in the electric field which can be measured,” said Adam Quinn, Fermilab engineer and project principal investigator.

However, because electron spins are so small, densely packed, and sensitive to even the slightest disturbance, extracting information from spin qubits is quite difficult.

“The core challenge of this sensor is the readout, and the key to success is having the ability to read out information with minimal noise,” said Quinn.

To achieve this, Quinn and his fellow researchers are seeking new ways to use highly scaled readout techniques based on cryogenic application-specific integrated circuits, or ASICs, which would be co-designed using Diraq’s qubit sensor. ASICs are manufactured the same way as the chips that power most electronics today. However, they will use specialized design and layout techniques to achieve superior performance, particularly in extreme environments, such as in a cryogenic chamber.

The Fermilab team is building on prior work at Fermilab on the readout of skipper charge-coupled devices, or skipper CCDs. Engineers developed skipper CCDs to increase the readout accuracy by overcoming noise. By using an action called skipping to move the charge back and forth multiple times, skipper devices enable a more precise measurement at the single-electron level. The Fermilab team plans to apply this innovation to the readout of qubits, with several iterative chip designs that will allow them to more tightly integrate the qubits and readout electronics. They believe this will ultimately lead to a low-power, highly sensitive detector.

Fermilab has been developing novel readout chips for particle physics experiments for many years. Now, engineers and scientists will employ some of these same types of microelectronic circuits and apply them to the development of the new sensor.

Scaling up

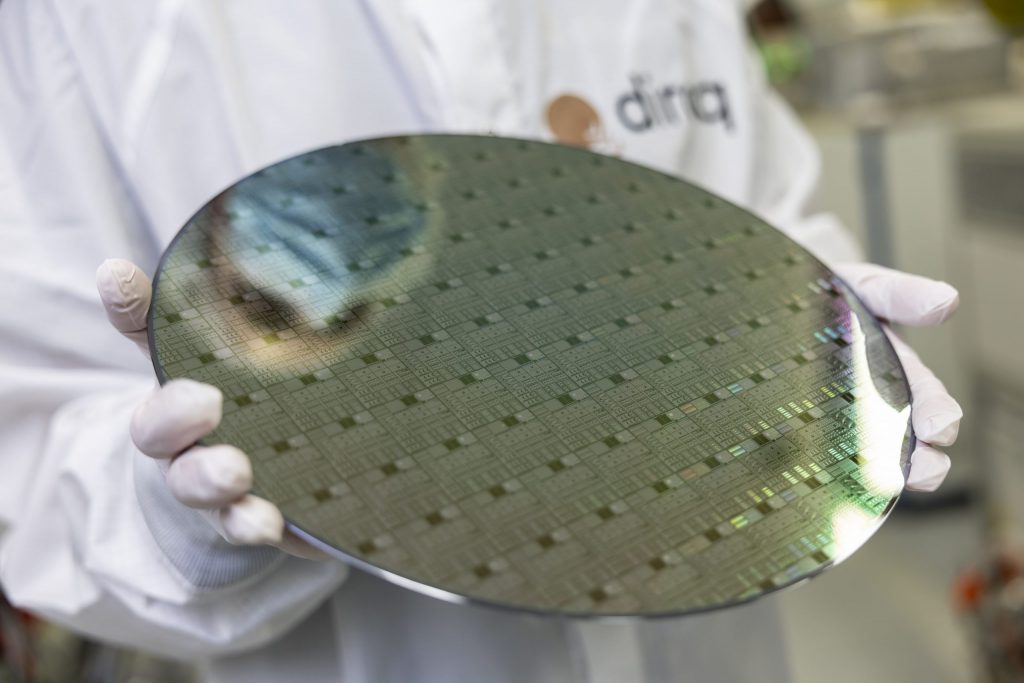

However, producing the quantity of qubits needed — potentially thousands — putting them together on a silicon chip, and making them work properly is not easy. During the manufacturing process, each one must be nearly identical and must perform similarly to the others.

Diraq, a company with world-leading expertise indeveloping spin qubits in silicon, is one company that is well positioned to manufacture spin qubits at the scale needed. Silicon is the preferred material because the industrial infrastructure to produce it is firmly established.

“In addition to quantum computing, the inherent characteristics and material properties of silicon spin-based qubits offer significant promise for large quantum-sensing array technology and particle detection applications,” said Andrew Dzurak, founder and CEO of Diraq.

“By utilizing high-precision fabrication processes we are looking to enable the production of quality controlled integrated silicon spin qubits at cost-effective and commercial volumes. This technology has the potential to underpin the development not only of large-scale quantum computers but large-scale quantum sensing platforms,” he said.

One step at a time

Over the next five years, the goal is to combine the two technologies — spin qubits and skipper readout technology — onto a single chip. However, to get there, they will build several prototypes.

“We’re going to start out by re-using existing chips and putting them together,” said Quinn. “We expect that to be a good proof of concept, but one lacking great performance. Then, over the next few years, we’re going to design better and better ASICs to improve performance.

Fermilab and Diraq will be joined on the Quandarum project by scientists from University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of Chicago and Manchester University, who will be developing algorithms and modeling the interactions of the physics phenomena. All participating institutions are seeking to leverage the technology being developed for the mutual benefit of the Quandarum project and the high-energy physics research they are conducting.

“This project exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation to advance quantum technologies for fundamental science,” said Fermilab Microelectronics Division Head Farah Fahim.

“By combining Fermilab’s expertise in extreme environment electronics and constructing sensitive large-area detectors with Diraq’s world-class capabilities in silicon spin qubits, the Quandarum project will push the boundaries of quantum sensing to tackle one of the most profound mysteries of our universe,” said Fahim.

Quandarum is funded for a total of five years.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.