An international group of more than 260 scientists have produced one of the most stringent tests for the existence of sterile neutrinos to date. The scientists from two major international experimental groups, MINOS+ at the Department of Energy’s Fermilab and Daya Bay in China, are reporting results in Physical Review Letters ruling out oscillations into one sterile neutrino as the primary explanation for unexpected observations from recent experiments.

MINOS+ studies the disappearance of muon neutrinos produced by a Fermilab accelerator and propagating to an underground detector in northern Minnesota 735 kilometers away. Daya Bay uses eight identically designed detectors to precisely measure how electron neutrinos emitted by six nuclear reactors in China “disappear” as they morph into other types.

Neutrinos are elementary particles that, like electrons, cannot be broken down into smaller components. They are unlike any other particle known to exist in that they are able to penetrate extremely large amounts of matter without stopping. If a neutrino is shot from the surface of Earth toward its center, there is a very large probability that it will emerge intact on the other side.

The MINOS+ and Daya Bay neutrino experiments have combined results to produce most stringent test yet for the existence of sterile neutrinos. In the MINOS+ experiment, Fermilab accelerators sent a beam of muon neutrinos through a detector located on the Fermilab site. The beam traveled 450 miles underground to a far detector, pictured here, in northern Minnesota. Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab

There are three known types of neutrinos: electron, muon and tau. About two decades ago, scientists found that they can morph from one type into another through a phenomenon called “neutrino oscillation,” a discovery that was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in physics. For instance, a neutrino created as an electron type traveling through space can later be identified as a muon type or tau type.

Even though the vast majority of accumulated data to date can be explained by three known neutrinos, a few experiments have reported anomalous observations suggesting the existence of additional types. Among these are the LSND experiment at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the MiniBooNE experiment at Fermilab. Both exposed their detectors to a beam of muon neutrinos and reported an excess of electron neutrino candidate events beyond what would be expected from oscillations involving only the three known types of neutrino, but possibly reconcilable if a new type of neutrino – a sterile neutrino – was involved. Sterile neutrinos would not be directly detectable, but their oscillation with the three known neutrinos would provide a unique pathway to establish their existence.

However, the new results from Daya Bay and MINOS+ question this possibility as an explanation of LSND and MiniBooNE results.

“The stakes are high; if this tantalizing interpretation of the anomalous results was confirmed, a revolution in physics would ensue. Sterile neutrinos would become the first particles to be found outside the Standard Model, our current best theory of elementary particles and their interactions. They could also be a candidate for dark matter and might have important consequences in cosmology,” said Daya Bay scientist Pedro Ochoa-Ricoux, associate professor of physics and astronomy at UC Irvine.

“This close collaboration of MINOS+ and Daya Bay scientists enabled the combination of two complementary world-leading constraints on muon neutrinos and electron antineutrinos disappearing into sterile neutrinos,” said Alexandre Sousa, associate professor of physics at the University of Cincinnati and one of the MINOS+ scientists who worked on the analysis. The disappearance of both particles needs to occur if electron (anti)neutrinos are to appear in a muon (anti)neutrino source via sterile oscillations with a single sterile neutrino. “So the combined result is a very powerful probe of the sterile neutrino hints we have to date.”

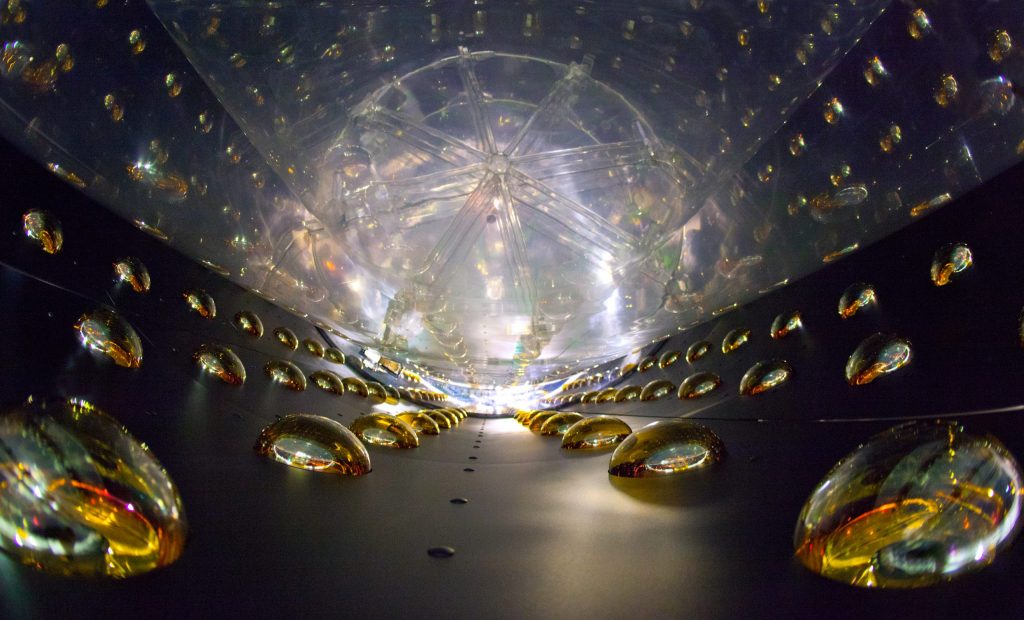

The Daya Bay neutrino detector walls are lined with photomultiplier tubes. The tubes are designed to amplify and record the faint flashes of light that signify an antineutrino interaction. Photo: Roy Kaltschmidt, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

The neutrino disappearance measurements by MINOS+ and Daya Bay are now so precise that they essentially rule out explaining the combined anomalous observations from LSND, MiniBooNE and other experiments solely through sterile neutrino oscillations, according to Ochoa-Ricoux.

“We would all have been absolutely thrilled to find evidence for sterile neutrinos, but the data we have collected so far do not support any kind of oscillation with these exotic particles,” he said.

The combined analysis reported by Daya Bay and MINOS+ not only ruled out the specific kind of sterile neutrino oscillation that would explain the anomalous results but also looked for other sterile neutrino signatures with never-before-achieved sensitivity, yielding some of the most stringent limits on the existence of these elusive particles to date.

“The two experiments use multiple detectors with well-understood uncertainties and have collected an unprecedentedly large number of events. Requiring consistency between the data sets of the two experiments provides a very rigorous test of sterile neutrino existence,” said MINOS+ spokespersons, Jenny Thomas, professor at University College London, and Karol Lang professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

“This joint effort very effectively tackles a fundamental problem in physics,” said Daya Bay spokespersons Kam-Biu Luk of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and UC Berkeley and Jun Cao of the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing. “While there is still room for a sterile neutrino to be lurking in the shadows, we have significantly shrunk the available hiding space.”

The MINOS+ and Daya Bay neutrino experiments are supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Drawn to physics by his desire to understand how things work, postdoctoral researcher David Sweigart of Cornell University now helps test the most fundamental theory of the construction of the universe — the Standard Model of particle physics.

For his Ph.D. dissertation, Sweigart analyzed the first year of data from Fermilab’s Muon g-2 experiment, collected in 2018. His thesis, “A measurement of the anomalous precession frequency of the positive muon,” has won the 2020 Universities Research Association Thesis Award, an annual recognition of the most outstanding work for a thesis conducted at or in collaboration with Fermilab.

“David’s thesis covers the theoretical motivation for Fermilab’s Muon g-2 experiment and then describes his technical work so we all can understand the reliability of the measurements,” said Chris Stoughton, Fermilab scientist and URA Thesis Award Committee chair.

The muon is a heavy cousin of the electron, and its mass and lifespan allow researchers to observe its properties very precisely. By studying the muon’s magnetic moment — which tells us the strength and orientation of its internal magnetic field — the Muon g-2 experiment focuses on a potential discrepancy between theory and experiment that may shed light on gaps in the Standard Model.

Previous experiments, most recently at Brookhaven National Laboratory, have found that, when shot through a uniform magnetic field around a particle storage ring, muons seem to spin in a way that differs slightly from the Standard Model’s predictions, which could result from interactions with yet undiscovered particles. With ultraprecise measurements of the muon’s “spin precession frequency,” Fermilab’s Muon g-2 experiment aims to reduce the Brookhaven experiment’s uncertainty range by a factor of four.

When combined with an equally precise average value for the strength of the magnetic field in the ring, measuring the precession frequency will help pin down the muon’s anomalous magnetic moment — and determine whether the disagreement between the measured value and the theory’s prediction is significant enough to warrant a revision of the Standard Model.

On the other hand, a confirmation of the Standard Model on this scale would be groundbreaking in itself.

“It will be exciting either way. Even if we found that we were consistent with the Standard Model’s prediction, our result would have a significant impact because it would place a tight constraint on current and future models for new physics,” Sweigart said.

“URA is very pleased to recognize David’s outstanding and creative work. His curiosity and drive have enabled him to break new ground in muon science and make significant contributions to his field and to Fermilab,” said URA Executive Director Marta Cehelsky. “He has a promising career ahead and his work will no doubt continue to impact high-energy physics for years to come.”

Sweigart’s 300-page thesis analyzes the first year of measurements since the experiment started collecting data at Fermilab in 2018. It also provides a detailed description of the program’s background, methods, challenges and uncertainties.

“I’ve lost count of the times David has answered a question with ‘I have a plot of that in my thesis.’”

The thesis highlights Sweigart’s contributions to each stage of the experiment. In the construction phase, he worked on hardware that provided the heart of the experiment, allowing researchers to detect particles given off by the muons as they decay. He then developed software to handle serious issues, including the “pileup” that results when these particles arrived at the detector back-to-back too quickly. Finally, he and his team provided one of the experiment’s six independent analyses of the precession frequency of the muon, which was further validated by Sweigart’s rigorous examination of each potential source of systematic bias.

A few key values are shielded from researchers to prevent them from unconsciously biasing the measurements, so Sweigart and his colleagues remain blind to the results of the experiment for now. Once the precession frequency and magnetic field measurements are cross-checked to a confident consensus, the concealed values and magnetic moment will be revealed at a future “unblinding ceremony,” and Sweigart’s exhaustive thesis will serve as a roadmap to explain and justify the findings.

“There’s just so much in David’s dissertation,” said James Mott, Wilson fellow at Fermilab and Boston University adjunct assistant professor. “I’ve lost count of the times David has answered a question with ‘I have a plot of that in my thesis.’”

Fermilab is managed by the Fermi Research Alliance LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. FRA is a partnership of the University of Chicago and Universities Research Association Inc.

Work on the Muon g-2 experiment is supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Fermilab is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.