On Nov. 21, DOE Undersecretary for Science Paul Dabbar visited Fermilab and took a tour of the laboratory. Dabbar serves as the science and technology advisor to Energy Secretary Rick Perry and, as part of his portfolio, oversees the Office of Science and its national labs. Dabbar was previously the managing director for mergers and acquisitions at J.P. Morgan & Co. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and Columbia University, he served as a nuclear submarine officer aboard the USS Pintado.

During his visit, Dabbar met with the Fermilab management team, local Congressman Randy Hultgren, members of the DOE Fermi Site Office, and about 20 scientists, including seven recipients of Presidential and DOE Early Career awards. Discussion covered the lab’s mission and projects, including the international LBNF/DUNE project and the broad international participation in the project.

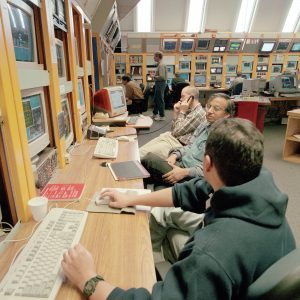

This is what the Main Control Room was like in the 2000s. But when there was an unscheduled power outage, what did these industrious folks do? Photo: Fred Ullrich

Sometime in the early 2000s, I remember, we had an unscheduled power outage. I had gotten a call at home at about 11 p.m. from someone in the Main Control Room to come in to restart my equipment since power restoration was imminent. So I made the 45-minute drive to the lab and made the right-hand turn from Pine Street toward the high-rise building (which is near the Main Control Room) just in time to see all the lights go off again. I had decided that under the circumstances, it was better for me to stick around the Main Control Room and wait for word from the power company or the people in the lab’s High Voltage Group than to make the drive back home just to turn around and come back at any moment.

Well, our group waited … and waited. We had already configured our equipment into a safe mode for when the power returned. There was nothing to do but immerse ourselves in all the line drawings sprawled out on the Crew Chief desk and debate what had happened. Nobody knew if the problem could be fixed quickly or if there was going to be an extended power outage. It would turn out to be a long wait into the morning.

Then, at about 8 a.m., I heard some commotion outside, so I decided to go see what was happening. Outside, in the Main Control Room parking lot, there was a pickup truck, and in the back of the truck was an 8-kilowatt generator. About four or five people were gathered around this generator. One person was pulling and pulling on the generator rope trying to get it started. Another one stepped in and took out the needle valve for inspection. Somebody else grabbed a hammer and started tapping on the float bowl of the carburetor. Try as they may, they just couldn’t get the engine started. Next the spark plug came out. They were all feverishly working on this generator with urgency as if it were an emergency.

I felt a sense of dedication and devotion to the lab seeing all these people pitching in to help get this generator started. I was still very new at the lab, so seeing all this teamwork made a very good impression on me. But I wondered, what was all the fuss about? What could they possibly be trying to power up after the power being off for 10 hours? The computer room? A sump pump? Was is something necessary to prevent disaster?

So I followed the huge industrial sized extension cord from the parking lot, through the doorway, and into the kitchen next to the Main Control Room, where it was plugged into a coffee pot.

The following statement was issued today by the International Committee for Future Accelerators, a 16-member body created in 1976 to facilitate international collaboration in the construction and use of accelerators for high energy physics. Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer is a member and past chairperson of ICFA. ICFA’s full press release is available at Interactions.org.

ICFA statement on the ILC operating at 250 GeV as a Higgs boson factory

The discovery of a Higgs boson in 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN is one of the most significant recent breakthroughs in science and marks a major step forward in fundamental physics. Precision studies of the Higgs boson will further deepen our understanding of the most fundamental laws of matter and its interactions.

The International Linear Collider (ILC) operating at 250 GeV center-of-mass energy will provide excellent science from precision studies of the Higgs boson. Therefore, ICFA considers the ILC a key science project complementary to the LHC and its upgrade.

ICFA welcomes the efforts by the Linear Collider Collaboration on cost reductions for the ILC, which indicate that up to 40 percent cost reduction relative to the 2013 Technical Design Report (500 GeV ILC) is possible for a 250-GeV collider.

ICFA emphasizes the extendability of the ILC to higher energies and notes that there is large discovery potential with important additional measurements accessible at energies beyond 250 GeV.

ICFA thus supports the conclusions of the Linear Collider Board (LCB) in their report presented at this meeting and very strongly encourages Japan to realize the ILC in a timely fashion as a Higgs boson factory with a center-of-mass energy of 250 GeV as an international project1, led by Japanese initiative.

In the LCB report, the European XFEL and FAIR are mentioned as recent examples for international projects.

Charles Thangaraj holds a model of the compact accelerator he recently received a grant to develop. Photo: Reidar Hahn

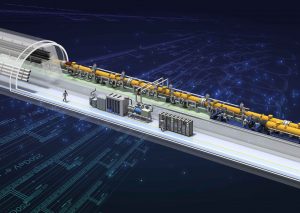

Fermilab scientist Jayakar ‘Charles’ Thangaraj has been awarded $200,000 from the Accelerator Stewardship Program of the U.S. Department of Energy to develop the design of a new, compact high-power accelerator. Collaborators are conceptualizing the potential use of this electron accelerator, based on superconducting radio-frequency (SRF) technology, in treating municipal biosolids and wastewater in collaboration with the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD) of Greater Chicago.

The grant builds on the previous work conducted by a team at the Illinois Accelerator Research Center (IARC) at Fermilab, specifically the work to design a one-megawatt electron accelerator – toward the top end of typical industrial electron accelerator power.

The results of simulations from that initial effort were encouraging enough that the IARC team proposed an accelerator system with a truly revolutionary 10-megawatt power output.

“Our simulations gave us positive results and encouraged us to pursue a higher-powered machine,” said Thangaraj, who is the science and technology manager at IARC. “I am thrilled to hear this proposal was awarded, we are ready to investigate.”

Municipal biosolids produced at MWRD’s water reclamation plants are generated through processes to remove larger, suspended solids from the water and organic pollutants, as well as to physically or chemically kill pathogens. In the Chicago area, treated water is then allowed to flow into local waterways without risk of harming the ecosystem. The byproducts from the water reclamation process are further treated to recover nutrients and energy and converted into a final product as biosolids that are beneficially used as fertilizer or soil amendment.

With an electron accelerator, the flowing water is exposed to a beam of highly energetic electrons, which create radicals in the solution that can disrupt chemical bonds. This will help kill pathogens in the water and the biosolids and increase the efficiency of recovering energy and nutrients from the biosolids.

This electron beam treatment technique has a few advantages. Firstly, because the treatment technique is physical and involves only a burst of electrons, the need for possibly harmful additional chemicals can be eliminated. Commonly used chemicals for inactivating pathogens in water, such as chlorine and ozone, can leave further residuals in the water, can be expensive to produce, or require filtration to avoid toxicity to workers at treatment centers.

Further, the technique can destroy organic contamination and pharmaceuticals that might otherwise survive conventional treatment.

While chemical and biological treatment processes require carefully controlled conditions and target specific contaminants, electron beam treatment is broadly effective and requires only an electricity supply to run.

The treatment process is also rapid, able to handle chemical and biological hazards simultaneously, and especially with the increased portability of this new conceptual design from IARC, easily adaptable to existing plant designs and layouts.

Accelerators for social impact

Fermilab’s mission is to build and operate world-class particle physics facilities for discovery science. In building such high-precision physics machines, the technologies that are developed can also have an impact on U.S. industry and wider society. IARC’s complementary mission is to take cutting-edge inventions from the lab and adopt those into real-life products and solutions. The IARC compact accelerator is a case in point.

“IARC’s compact SRF accelerator is a pioneer in the industrial accelerator space,” Thangaraj said.

Several Fermilab-developed technologies are combined to build this novel accelerator, and the platform technology has a range of potential applications, including extending the longevity of pavements and medical sterilization.

New innovations

SRF accelerators, including those currently used at Fermilab, rely on being cooled down to around 2 Kelvin, colder than the 2.7 Kelvin (minus 270.5 degrees Celsius) of outer space. The components need to operate at cold temperatures to be able to superconduct: the ‘S’ in SRF. The typical way to do this is by immersing the cavities in liquid helium and pumping on the helium to lower its pressure. However, producing and maintaining subatmospheric liquid helium requires complex cryogenic plants – a factor that severely limits the portability and therefore the potential applications of SRF accelerators in industrial environments.

“We are able to do away with liquid helium through a combination of recent advancements in superconducting surface science and cryogenics technology. This allows us to operate at a higher superconducting temperature in our cavities and cool them in a novel way,” said Thangaraj, who was also awarded $1.47 million to develop this crucial Fermilab-patented technology from the Laboratory Directed Research Development program.

“Breaking the need for a supply of liquid helium makes the accelerator very attractive for installation within MWRD’s existing infrastructure,” he said.

Though such real-life solutions are exciting and promising, the reality remains a few years away. Nevertheless, IARC has already started talking to several stakeholders in the industry.

“When we turn the tap or twist open a bottle, we often don’t realize that behind such modern conveniences are some of the most amazing technologies that deliver clean and safe water,” Thangaraj said. “Water is such a precious resource on our planet. We must use our best technologies to protect it. Electron beam technology could be a practical and effective way for water treatment in the future. Now is the time to develop it.”