Inventors, creators and entrepreneurs at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory were recognized for their inventions and novel ideas by Fermilab’s Office of Partnerships and Technology Transfer at the 2024 Inventor Recognition Ceremony on Feb. 29.

In 2023, 12 new patents were issued with 16 inventors associated with those patents at Fermilab.

“The first U.S. patent granted to an employee of the National Accelerator Laboratory was awarded to Quentin A. Kerns on Jan. 25, 1972; Patent No. 3,638,127, titled ‘Stabilization System for Resonant Cavity Excitation,’’’ said Cherri Schmidt, manager of the Office of Partnerships and Technology Transfer at Fermilab. “We have continued to build on the shoulders of these early inventors to continuously improve accelerator and detector technologies to advance our science.”

Fermilab inventors, creators and entrepreneurs are honored at the 2024 Inventor Recognition Ceremony on Feb. 29. Photo: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

The patent awardees from 2023 recognized at the ceremony included:

- James Hoff with co-inventors Sadeep Miryala and Gregory Deptuch, both formerly at Fermilab and now at Brookhaven National Laboratory: Soft error-mitigating semiconductor design system and associated methods

- Timothy Ring: Vertical high-pressure rinse machine

- Alexander Shemyakin and Ding Sun: Fast faraday cup for measuring the longitudinal distribution of particle charge density

- Michael Geelhoed: Electron beam treatment for invasive pests

- Thomas Kroc and Robert Kephart: Inspection system of wellbores and surrounding rock using penetrating X-rays

- Thomas Kroc: Supported X-ray horn for controlling e-beams

- Jin-Yuan Wu: Gated ring oscillator with constant dynamic power consumption

- Sujit Bidhar: Methods and systems for electrospinning using low power voltage converter

- Juan Estrada, Guillermo Fernandez Moroni, Andrew Lathrop and Javier Tiffenberg: Connector interface assembly for enclosed vessels and associated systems and methods

- Tom Zimmerman and Farah Fahim of Fermilab, and Gregory Deptuch — formerly of Fermilab and now at Brookhaven National Laboratory: Compact, low power, high resolution ADC per pixel for large area pixel detectors

Fermilab’s Office of Partnerships and Technology Transfer recognized 50 lab employees who disclosed inventions and software ideas for potential patents. DOE Early Career Awardees Silvia Zorzetti and Guillermo Fernandez Moroni were recognized, as well as other Fermilab employees who received external awards or made out-of-the-box advancements in their fields. Katrina Porter represented the Fermi Site Office for DOE also helped hand out awards.

Guest speakers at the ceremony

Vanessa Chan, chief commercialization officer for DOE and director of the Office of Technology Transitions provided a message through video. “I have so much admiration for the inventors, creators and entrepreneurs at the forefront of fundamental science,” said Chan. “You make the discoveries that so often transform and dramatically improve our quality of life, security and environment. The entire nation, really the entire world, is in your debt.”

Vanessa Chan from DOE’s Office of Technology Transitions provides remarks during the ceremony. Photo: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

Chan talked about the importance of training the next generation of scientists and researchers. Some of the examples she included were the Commercialization Internship Program between the national labs, including Fermilab, and her office. Chan also talked about programs that provide undergraduate students with the opportunity to work in quantum science labs through the Chicago Quantum Exchange’s Open Quantum Initiative.

Samir Mayekar, the director of the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the University of Chicago, said, “We are advancing the frontiers of science and have a fortress of intellectual property, know-how, engineering and equipment backing us. I believe the wind is at our backs for the first time in generations — perhaps since the founding of the national lab system or the early days of semiconductor developments in Silicon Valley.”

Rich Goffi, director of strategy at Fermilab, speaks to the importance of tech transfer to Fermilab’s mission and future. Photo: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

Samir Mayekar snaps a selfie with attendees of the award ceremony. Photo: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

As part of its Accelerate Innovations program the U.S. Department of Energy is funding three emerging technologies projects involving researchers at its Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. They are among eleven DOE national lab projects awarded a total of $73 million in funding over a two-year period. The funding aims to speed up the transition of new technology from discovery to industry.

Superconducting photon detector technology

The first project, led by Fermilab, will develop and extend the capabilities of existing superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors, also known as SNSPDs. The technological advances could enable discoveries in fundamental science. Fermilab scientists are particularly interested in using them to expand the search for axions—hypothetical particles that may make up the mysterious dark matter in the universe.

“This work may translate into an enormous scientific opportunity,” said Fermilab’s Si Xie, principal investigator for the project. “Our project and funding are specifically for particle physics applications including dark matter searches. But the result could have wide-ranging impact on diverse fields of science including the search for far away planets, environmental monitoring and climate change applications, and studying some biochemical processes.”

SNSPDs are ultrafast light sensors that use a thin superconducting wire to detect single photons. Scientists operate them at very low temperatures and send an electric current through the wire just below the maximum the superconducting material can withstand without turning normal conducting. When a single photon hits the nanowire, it transfers just enough energy to push the nanowire out of its superconducting state. This causes the material to develop electrical resistance, which creates a measurable voltage pulse.

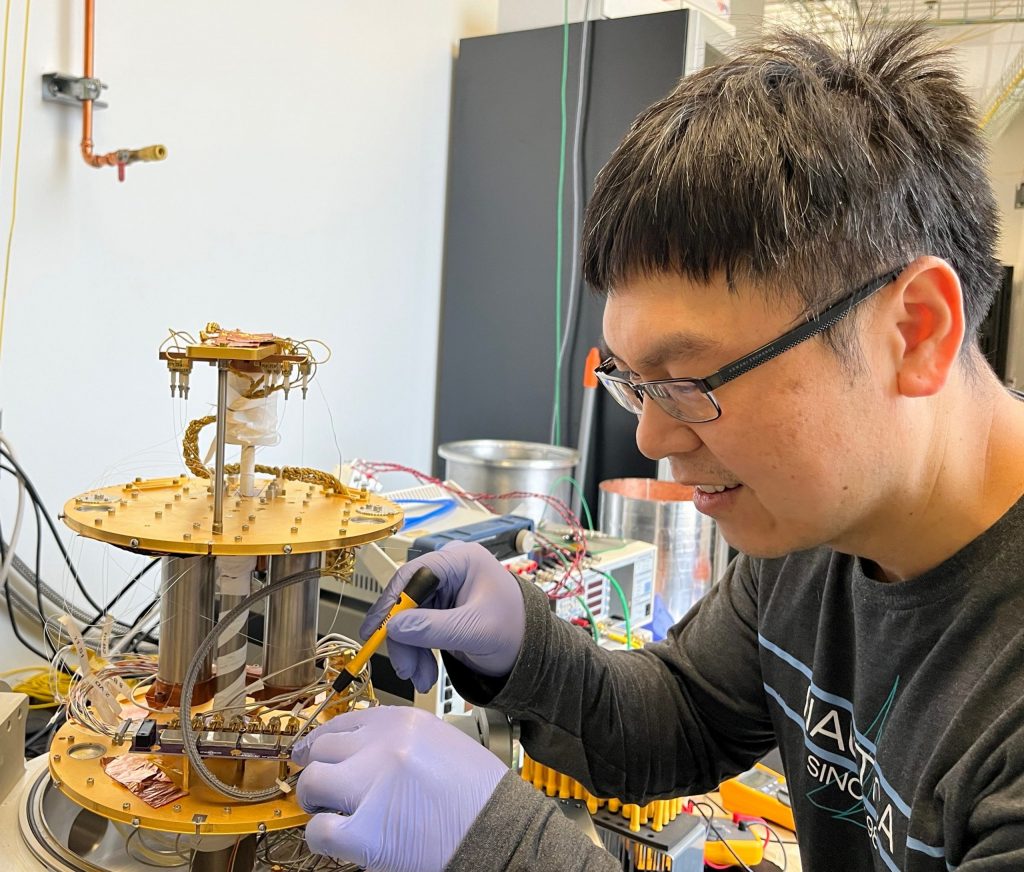

Fermilab scientist Si Xie mounts a superconducting nanowire single photon detector inside a cryostat. He and his colleagues will use the detector to look for light created by dark matter particles. Photo: Christina Wang, Fermilab

The new SNSPD detectors will use very little energy and be ideal for detecting faint photon signals formed by particle interactions that may signal axion existence. The project aims to enable scientists to seek low-energy light from axions with masses in the mid-infrared range, equivalent to 0.05-1 electronvolts. This mass range has remained unexplored so far; no previous detection technology is sensitive enough to such low-energy signals.

To achieve their goal, the project team aims to construct and test prototype detectors with energy thresholds 20 or more times lower than that of conventional SNSPDs. Lower energy thresholds aid in efficient detection of low-frequency, low-energy photons in this range.

As part of their work, the project team will develop specialized antenna structures. These will enable, for the first time, mid-infrared SNSPD detectors with an active sensor area larger than 1 square millimeter. They will also focus on improving the ultrafast signal readout by developing novel sensor electronics that extract and detect particle signals at greater resolution than existing SNSPDs.

Developing 3D integrated sensing solutions

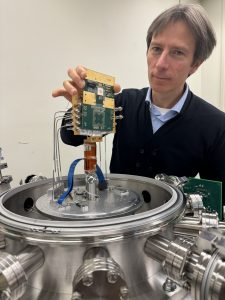

Fermilab project co-lead Davide Braga holds an integrated circuit developed at Fermilab for extreme environment applications. Scientists aim to make this sensor much tinier while increasing its accuracy and timing. Photo: Albert Dyer, Fermilab

Anything using microelectronics today requires a lot of functionality squeezed into a tiny amount of space. This includes particle physics experiments, which need low-power detectors with precision timing and position capabilities and high-throughput readout. Conventional two-dimensional chip technology has reached its limits and can no longer meet the ever more stringent requirements.

To help solve this problem, DOE has funded a new project led by SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. The project will enable large-scale particle sensors with three-dimensional integrated circuits to process much smaller, much faster signals at a higher level of precision. Fermilab is a major contributor to this project. Artur Apresyan and Davide Braga are the project co-investigators at Fermilab.

The sensors will be part of 3D heterogeneously integrated detectors—essentially stacked wafers, each layer with its own functionality. The wafers are connected at the micrometer scale. This eliminates traditional larger interconnections and significantly improves the fidelity of signals all along the chain.

“You can have a lower power because you are getting signals with low noise, so you can use resources more optimally and you can do a lot more with those resources,” said Apresyan.

While the current generation of this technology uses rather large pixels, around one millimeter, the goal is to scale this down to 50-micron pixels.

“We want to demonstrate 3D integrated sensors that utilize Low Gain Avalanche Detector particle sensors that provide very fast timing information,” said Braga. “We intend to simultaneously achieve 10-micron position resolution and 10-picosecond precision timing while consuming low power and reaching high throughput rates.”

The team is also partnering with a commercial chip company to develop advanced manufacturing capability for this novel technology. Their fabrication know-how will be essential for the codesign of sensor and electronics for scaling, said Braga.

“As we develop the technology to fabricate novel detectors using cutting-edge industrial processes, the partnership will allow us to tap into advanced manufacturing facilities to develop sensors that perform sophisticated operations on the detector itself that were not possible before,” said Apresyan.

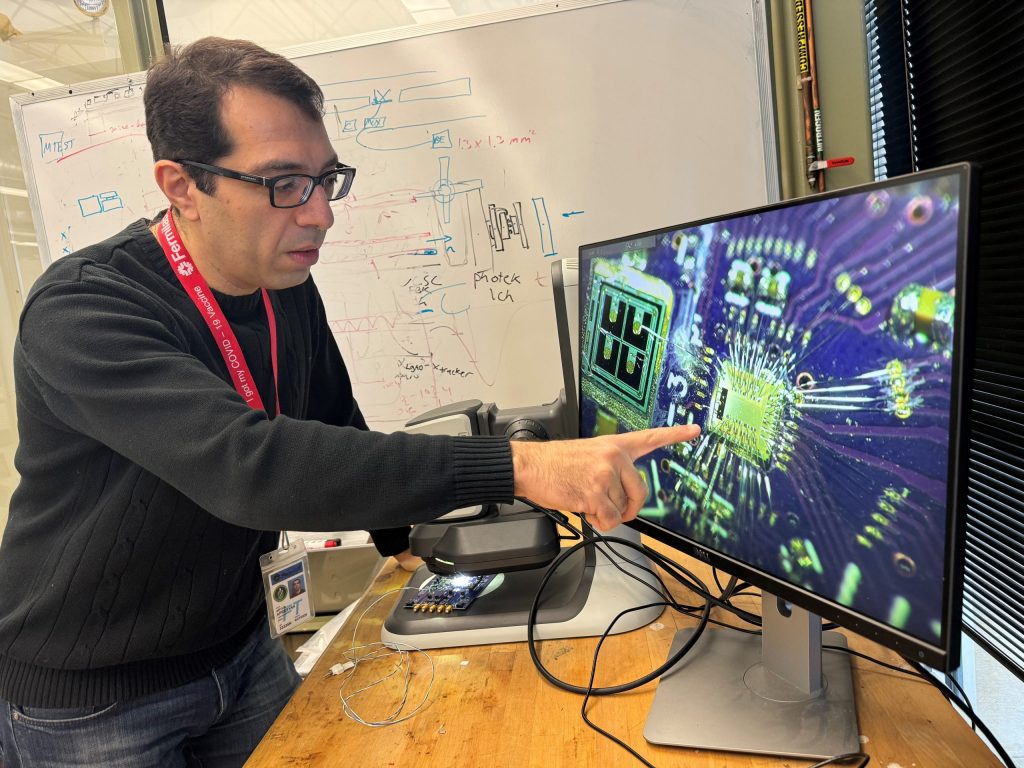

Artur Apresyan inspects the Fermilab-designed integrated circuit that will be used for precision timestamping of signals from silicon detectors. Photo: Cristian Peña, Fermilab

Compact accelerators for industrial applications

The third project is a collaboration between DOE’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility and Fermilab. It aims to advance the use of compact superconducting radiofrequency electron-beam accelerator technology for industrial processes. As part of the project, researchers at Jefferson Lab are focusing on further developing the particle accelerator technology. Fermilab will identify industrial applications and develop a technology roadmap to satisfy industrial needs.

“We’re investigating where an electron-beam accelerator could be a good fit and solve problems,” said scientist Slavica Grdanovska, principal investigator at Fermilab for the project. “We’re focusing on industrial processes—where you can maybe substitute conventional technologies with e-beam technology—or see if it can help make their current processes more efficient.”

By organizing a workshop with potential industry partners this spring, the project team aims to identify barriers to implementing this powerful technology.

“At this workshop, we want to show potential industrial partners the current status of our technology, identify processes in the industry where electron beams could make a difference, and focus on specific targets that need to be reached in the accelerator design for use in an industrial setting,” said Fermilab scientist Charles Thangaraj. “We are also seeking potential partners for system integration and production once these machines are ready.”

Fermilab and Jefferson Lab will then hash out the accelerator technology roadmap to reach those targets.

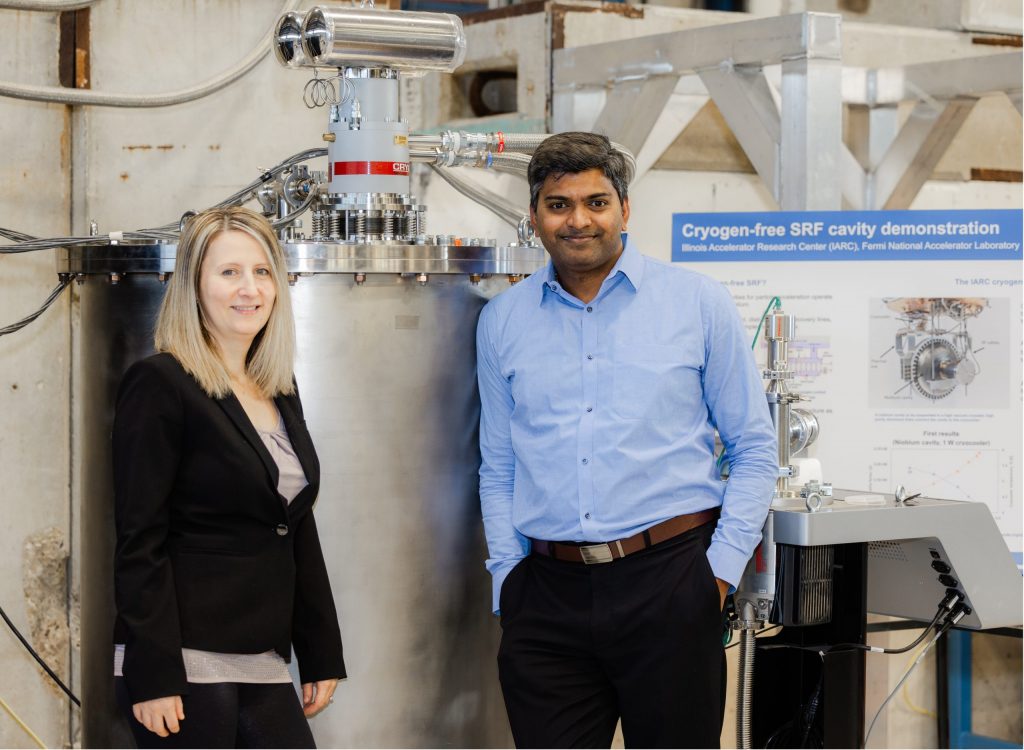

Fermilab scientists Slavica Grdanovska (left) and Charles Thangaraj stand next to the conduction cooled cryostat that houses superconducting accelerator technology for industrial electron beam applications. Photo: Tom Nicol, Fermilab

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.