Robert Wilson constructs “Acqua Alle Funi,” also known as the Hyperbolic Obelisk, in 1978. Photo: Fermilab

Robert Wilson was a man born out of his time.

He lived in America from 1914 to 2000, but he really belonged to the central Italy of the 1500s. He knew this, but was determined to make the best of the opportunities afforded by the 20th century.

Robert Rathbun Wilson was a son of a small American township called Frontier, Wyoming, but while his intellectual brilliance and talents soon took him to many more interesting places, he never forgot or underestimated his roots in small-time America.

His academic success took him to California, where he studied physics to doctoral level, studying under Ernest O. Lawrence on the theory of the cyclotron. By the time the United States entered the war he was working with Robert Oppenheimer, who recruited him as a group leader at Los Alamos, where he contributed to the building of the first atomic bomb. He then retired to a more peaceful existence as a professor at Cornell University.

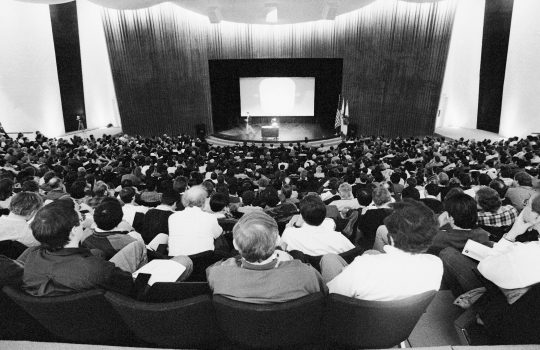

When in the 1960s United States decided to build the world’s largest particle accelerator, Robert Wilson was the obvious choice of a man to build it. A site was chosen on the prairie, 40 miles out of Chicago. Boring, flat farmland is not a very exciting place to attract the brains that would clearly be needed to man it.

“Acqua Alle Funi” has stood in the reflecting pond in front of Wilson Hall since 1978. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Robert Wilson was up to the challenge. His own personality and reputation were sufficient to attract the talent he needed, and he soon had a small team of potential group leaders with the requisite skills.

The site, about 10 square miles in extent, comprised more than 50 farms whose owners had been reimbursed by the government, some woods and an old cemetery. Wilson had the clapboard houses moved physically to make a charming little artificial village, found a site for the accelerator, which was to be a circular structure about a mile across, designed and built a laboratory building 15 stories high, stocked the site with a herd of American bison and the lakes with trumpeter swans, arranged for some of the land to be turned from farming back to its original tall grass prairie, and covered the site with sufficient roads for access. Characteristically, the roads are named after the Indian tribes that once inhabited the area.

As well as being a scientist, he was a sculptor and an architecture enthusiast, and the design of the high-rise building bore his influence. He covered the site with large abstract sculptures of his own design. At one time he took a course in welding so that he could realize his own art work. One of the pieces was an obelisk, placed at the end of a reflecting pool situated in front of the high-rise laboratory building. He called it “Acqua alle funi.”

* * *

In the early 1500s, Bernini and Michelangelo were busy building and decorating St. Peter’s cathedral in Rome. Some years later, it was desired to re‑erect in the middle of the circular colonnade an enormous monumental pillar from antiquity that was there. The pillar, made from granite and weighing many tons, was to be brought to a vertical position and dropped into a prepared hole so that it would stand and occupy the most prominent position at the center of the most important piazza in the world.

Elaborate preparations were made for the raising. A huge wooden structure was erected, with pulleys and ropes enabling the column to be pulled up by the combined efforts of hundreds of workers. A day was set aside. Everything was ready for the effort. As an additional guarantee of success, the Pope decreed that no one was to speak while the work was in progress, so that the instructions of the overseer could be clearly heard. The penalty for speaking is variously reported as having been death or excommunication.

The work began. The workers toiled at the ropes, and the pillar began to rise. The hot Roman sun ascended in the sky. As the angle of the great stone obelisk increased, so did the temperature of the ropes. The energy expended by all those people pulling heated them, and the blazing sun did nothing to help. In due course they became so hot they began to smoke. If they caught fire, the obelisk would come crashing down. It might even shatter.

The obelisk in St. Peter Square in Vatican City was erected in 1586. Photo: Staselnik

It was at this time that one of the workers, a Ligurian sailor called Bresca, decided that the rule of silence was less important than the success of the project. He shouted out: “Acqua alle funi,” meaning “water to the ropes.” The astounded overseer, realizing that this was useful advice, had water fetched and poured on the ropes. The project was saved. The obelisk adorns St. Peter’s Square to this day.

When it was reported to the Holy Father, he decided on clemency. The punishment was lifted, and the brave worker was rewarded. He and his heirs were given the privilege of a monopoly in the sale of palm leaves to pilgrims in St. Peter’s Square on Palm Sunday of each year. Apparently the family survives, and still enjoys the privilege.

Wilson erected his obelisk on the site of his laboratory in May 1978.

Frank Beck is a retired CERN staff member living in England. He spent two years at the Fermilab as head of research services when the Energy Saver was being commissioned.

Editor’s note: For more about the construction and installation of “Acqua Alle Funi,” including historic photos, check out the History and Archives Project website. A May 1978 FermiNews article (see page 2) reports on the sculpture installation.