The setting provided by founding Director Bob Wilson’s creative design of the National Accelerator Laboratory, the architecture of the buildings and his many sculptures are an enduring source of pride for those associated with Fermilab and, indeed, for the surrounding community. One of the sculptures that has gained widespread attention is “Tractricious,” a piece that graces the space in front of the Fermilab Industrial Building Complex.

The Industrial Center Building (one of Wilson’s designs) was completed in 1983, when Richard Lundy was head of the Technical Support Section (later renamed the Technical Division). When I became head of Technical Support the following year, I began to consider ways to improve the visual appearance of the space in front of the handsome new building.

We started by moving a large, rather unsightly helium compressor building, then located in front of the Industrial Complex, to a new location behind the industrial buildings. Then in 1986, trees and other landscaping features were added to the front of the Industrial Complex. Still, something was still missing.

The Industrial Center Building, part of the five building complex, is shown in October 1986 flanked by two of the other industrial buildings. Photo: Fermilab

The area bounded by the new Center Building and the neighboring Industrial Buildings formed an expansive grassy semicircle. The center lines of the three buildings formed a focus at the center of the semicircle. It seemed that this focal point might provide a natural location for a sculpture that would complement the symmetry of the building and the formal style of the landscape plan. It was an ideal location for a “Bob Wilson” sculpture.

Cryostat pipe left over from the construction of Tevatron magnets was used to build the sculpture “Tractricious.” Photos from the Technical Support files

When I approached Wilson about the possibility of a sculpture, he was enthusiastic. He sent me off to assess the availability of scrap stainless steel that might suggest a theme for the sculpture. Technical support technician TJ Gardner and others searched the places where obsolete, unwanted equipment and scrap materials were kept. We came back with a collection of photos for Wilson of what we thought looked promising (although without the practiced eye of an artist).

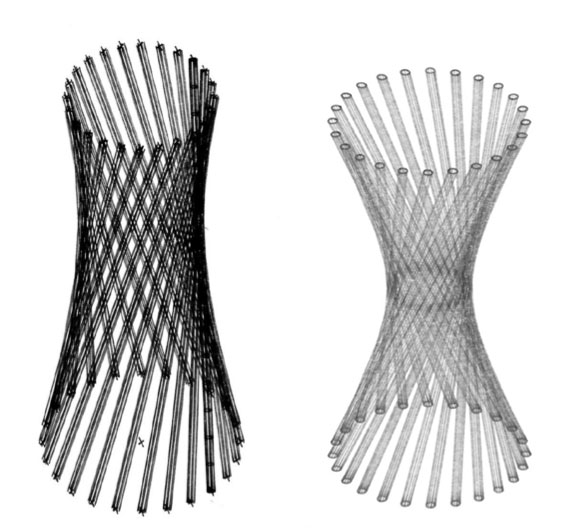

Wilson was intrigued by the stainless steel tubing left over from the recently completed construction of the Tevatron superconducting magnets. After assessing the available material, Wilson decided on an array of six-and-a-half-inch diameter stainless steel cryostat tubes in the form of a paraboloid. He considered several designs, including one in which the array was asymmetric vertically, but concluded that it was too suggestive of a cooling tower at a nuclear power plant.

These drawings show early design concepts for “Tractricious.” Drawings from the Technical Support files

Wilson settled on a final design consisting of 16 members, each 39 feet long. The length of each member was achieved by welding two Tevatron cryostat tubes together end to end. The welding was carried out under the supervision of Jerry Peterson and Luis Ramirez in the Technical Support machine shop. The use of cryostat tubes would symbolize the key role the Technical Support Section had played in producing the superconducting magnets for the Tevatron.

Technical Support engineer Tom Nicol went to work designing the pedestal and tube support system. He performed a careful structural analysis, including dynamic response to extreme wind conditions. Tom was confident of the engineering but did tell Wilson that, if the tubes were left open at the top as Wilson wanted, they might fill up with pigeon droppings. Kurt Kasules and George Mikota took care of the pedestal construction and alignment of the tubes.

Wilson derived the name Tractricious from tracktrix, a curve such that any tangent segment from the tangent point on the curve to the curve’s asymptote have constant length, a concept first introduced by Claude Perrault in 1670.

Once satisfied with the design and the name, Wilson began thinking about enhancements. He decided that the sculpture, having a vague resemblance to pipes in an organ, needed to sing with the passing breezes (perhaps inspired by a recently completed sea organ in San Francisco Bay).

Having some familiarity with pipe organs, I thought about that idea for a while and even imagined baffles at different distances from the top of the pipes that might produce different pitches. Alas, in the end the idea turned out to be impractical. Wilson also wanted the base of the sculpture to project above a surrounding reflective pool. While certainly a pleasing addition, the pool ultimately also turned out to be impractical due to our limited resources.

The next hurdle was to find outside funding to construct the pedestal and erect the pipes since these were not normal lab expenditures. I wrote to Stanka Jovanovic, then president of the Friends of Fermilab, appealing for the necessary funding, which we estimated to be about $10,000.

In January, 1987, the Friends of Fermilab Board of Directors unanimously agreed to support raising the funds. Robert Riley, a member of the Friends of Fermilab Board (and president of Gary-Wheaton Bank of Batavia), led the fundraising effort. Riley located interested donors in the community and before long the funds were in hand. The sculpture was completed in June 1988, a tribute, not only to Wilson but to Fermilab’s close relationship to the community.

An attractive feature of the laboratory site, “Tractricious” gets a fair share of photographic attention, as is evident in this gallery. Click on the magnifying glass icon in the lower right to see the photos in their true orientations (landscape or portrait).