A groundbreaking experiment at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, which will probe a narrow, previously unexplored region of mass where some scientists believe dark matter lurks, is one step closer to taking experimental data.

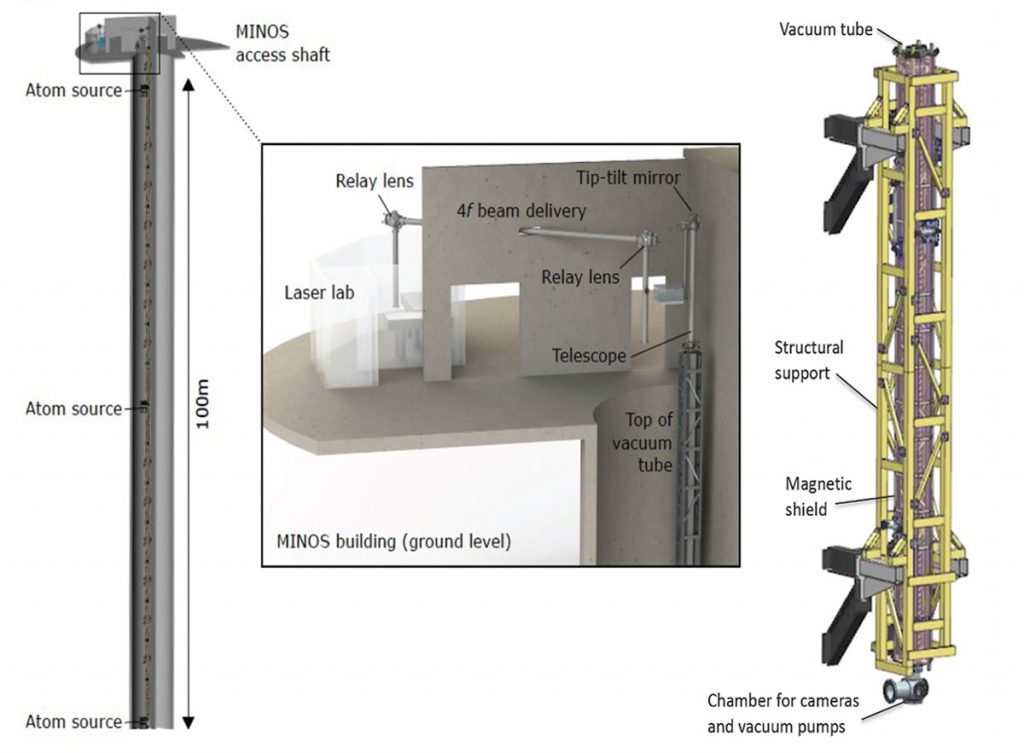

The Matter-wave Atomic Gradiometer Interferometric Sensor experiment — also called MAGIS-100 — is a collaboration that also includes Stanford University, Northwestern University and eight other research institutions in the U.S. and the U.K. The interferometer will occupy a 100-meter shaft at Fermilab used years ago for accessing underground experiments. Once constructed, MAGIS-100 will be the world’s largest vertical atom interferometer.

The project has reached an important milestone — construction is complete on a laser lab that will contain the infrastructure to generate high-power laser beams used to operate the interferometer. Construction began in 2023.

“Finishing the laser lab marks completion of our first major project construction.”

Jim Kowalkowski, MAGIS-100 project manager

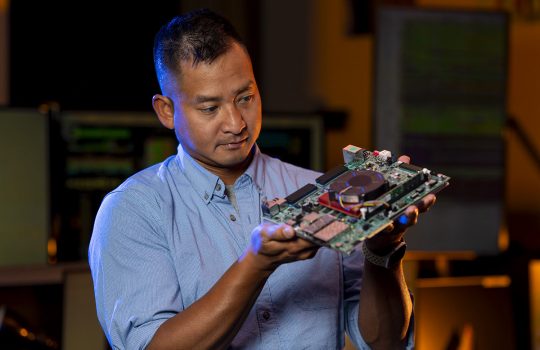

“Finishing the laser lab marks completion of our first major project construction,” said Jim Kowalkowski, MAGIS-100 project manager. “Now we’re moving experimental equipment into the laser lab; we’re doing a lot of testing; we’re characterizing different components to understand any problems and correct them if we can. A lot has to happen.”

In the experiment, strontium atom clouds colder than outer space will be dropped into the 100-meter shaft enclosing the interferometer. Carefully timed laser pulses work like beam splitters and mirrors for the atoms, splitting each cloud into two separate paths and then bringing them back together. Similar to what occurs when two rocks are thrown into a pool and the waves interfere with each other, any disturbance in one path will show up as an interference pattern on a camera lens.

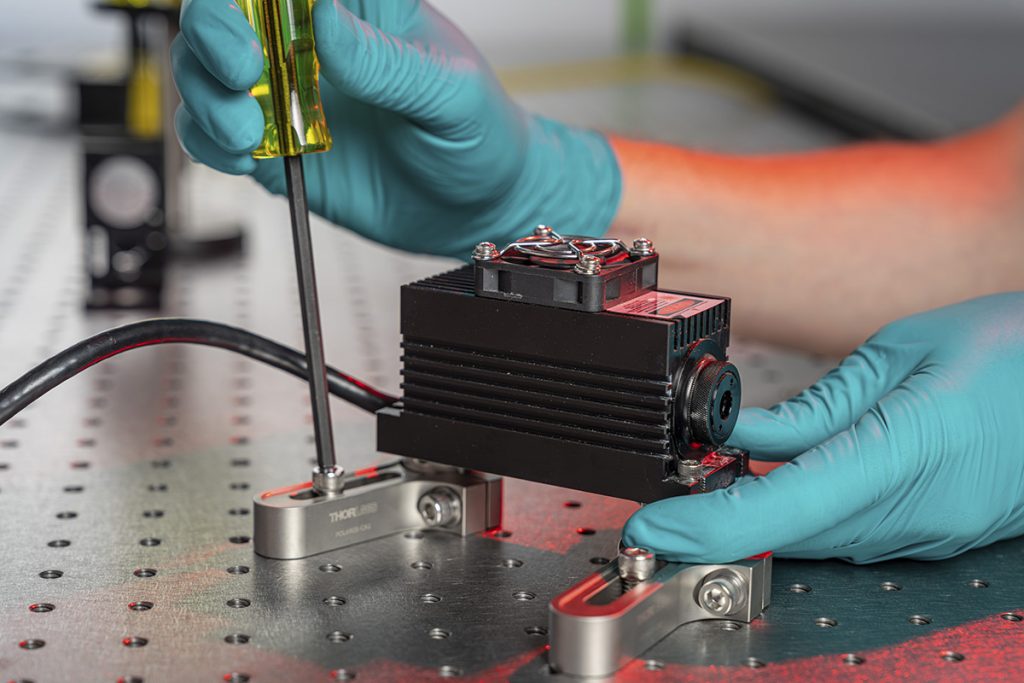

The interferometer will be incredibly precise, capable of detecting extremely small changes in gravitational fields that could detect difficult-to-observe phenomena, such as the presence of dark matter or gravitational waves. Scientists hope to use it to tease out ultralight dark matter by stimulating interactions between theorized particles of dark matter (axions), and regular matter (electrons or light). But before the experiment can begin to discover new physics phenomena, there is much work to do. The research team must now begin to set up and test the intricate laser systems that will feed the rest of the experiment.

The making of the world’s largest interferometer

The laser lab is fully enclosed to prevent light leakage, and a sophisticated laser safety interlock system is being built to control access to the room to prevent any accidental exposure. Before it can operate, Fermilab must certify the interlock system meets national laser safety criteria.

A sturdy tower redirects a tuned laser beam from optical tables that hold the main laser system to a transport tube running to the shaft that will hold a vertically mounted interferometer. Here, an optical telescope redirects and focuses the laser light so it is the right size and position to interact with the strontium atoms, all contained within a vacuum.

Three atom sources, being constructed by a group at Stanford University, will be placed at the top, middle and bottom of the interferometer. These devices will produce strontium atom clouds near absolute zero —negative 273.15 degrees Celsius. Special electrical fields will shuttle these clouds to an area where they are thrown upward and allowed to fall the length of the shaft. From there, the interferometry beams from the laser lab, directed by special timing systems, will take over, striking the clouds and causing them to split and rejoin the paths of the free-falling atoms. Imaging cameras throughout the interferometer will be used to record their behavior.

Considering the optics

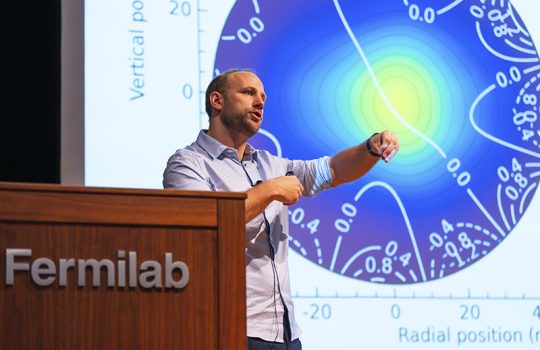

Now the painstaking process to study and characterize the full experiment environment begins. A team led by Tim Kovachy from Northwestern University is leading exploration into how each component is affected by outside sources — for example, how vibrations from the ground and building equipment contribute to fluctuations in the laser beam trajectory.

“The alignment of each component must be extremely accurate.”

Dylan Temples, MAGIS-100 researcher

“The alignment of each component must be extremely accurate,” said Dylan Temples, a researcher at Fermilab who works on MAGIS-100. “Even small vibrations or strain in the table on which the elements are set up might lead to noise or interference that could seriously impact the experiment.”

The team must ensure any interesting signals they observe are correctly attributed to actual physics phenomena, not from unknown sources that can masquerade as good observations. In addition, knowing about these unexpected negative effects allows them to adjust, ensuring everything is properly aligned and works as expected before the experiment runs.

“We have already made initial measurements of the mechanical resonances of the tower in the laser lab, which inform us how the tower will respond to vibrations,” said Kovachy.

In parallel to optics system testing, researchers are starting to test the 17-foot sections that will comprise the 100-meter vacuum tower, within which the vacuum pressure is extremely low, similar to that on the moon. Each section must be magnetically and electromagnetically insulated to prevent environmental signal interference. The welding process for the stainless-steel sheets used for the vacuum tubes can magnetize material along the seam, creating potential noise that could alter measurements during the experiment. Researchers use special measuring devices to locate these unwanted magnetic fields.

As the laser lab setup continues over the next year, construction will begin to prepare the shaft for installations of the vacuum tube sections and atom sources. Plans are to deliver the atom sources Stanford University is building in late 2026 and install them, along with the vacuum tube modules in 2027.

Installation of the MAGIS-100 experiment is currently on track to conclude at the end of 2027, along with some early data-taking. Commissioning is planned to begin in 2028.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

The MAGIS-100 project is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy. Collaborator funding is supplied through grants from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the U.K. Research and Innovation.