Bob Zwaska, a scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab, was watching a contestant on the cooking show Chopped spin sugar for their dessert when he realized the same principle might be applicable to accelerator targets.

One of the ways particle accelerators produce particles is by firing particle beams at targets. These targets are stationary, solid blocks of material, such as graphite or beryllium. When the beam collides with the target, it produces secondary particles, such as pions, which decay into tertiary particles, such as neutrinos and muons.

Future particle physics experiments are limited by the targets currently used in particle accelerators. One is the international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, a cutting-edge experiment hosted by Fermilab and developed in collaboration with more than 170 institutions worldwide. DUNE seeks to understand why matter exists in the universe by unlocking the mysteries of ghostly particles called neutrinos. To solve these mysteries, the accelerator beam used by DUNE needs to reach a power of at least 1.2 megawatts, twice the amount current targets can handle.

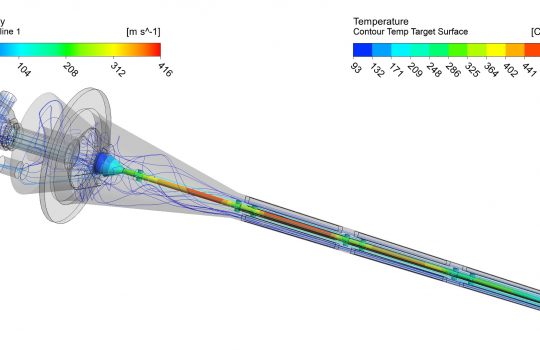

The point of collision between the beam and the target — an area significantly smaller than the target itself, varying between the size of an ant and the graphite in a mechanical pencil — is rapidly and repeatedly heated to above 500 degrees Celsius. This heat causes that tiny area to try to expand, but, because the currently used targets are solid, there’s no room for expansion. Instead, the hot spot pushes against the surrounding area over and over again, like a jack hammer. This has the potential to damage the target.

In electrospinning, a positive charge is applied to liquidized material to create thin strands that eventually harden into a solid, fibrous material. Photo: Reidar Hahn

When you dive into a pool, your collision with the water causes waves to ripple across the surface. When the waves reach the edge of the pool, they will rebound and cross over other waves, either destroying each other or combining to make a larger wave. In a pool, if a wave gets too large, the water can simply splash over the edge. In a solid target, however, if a wave gets too big, the material will crack.

At the Fermilab particle accelerator’s current beam intensities, this isn’t a problem, because targets can withstand the resulting waves for a long time. As Fermilab upgrades its accelerator complex and the intensity increases, that endurance time drops drastically.

“Worldwide, there is a push for higher-intensity machines to create rare particles. These targets have sometimes been the sole limiting factor in the performance of such facilities,” Zwaska said. “So, to research areas of new physics, we have to be pushing for new technologies to confront this problem.”

Tasked with coming up with an alternative target to use in high-powered accelerators, like the ones that will send beam to DUNE, Zwaska envisioned a target that consists of many twists and turns to prevent any wave buildup. This sinuous target would also be strong and solid at the microscale. He first tested graphite ropes, 3-D-printed fibers, and mostly hollow, reticulated solids before he stumbled upon the spun-sugar concept, which led him to electrospinning.

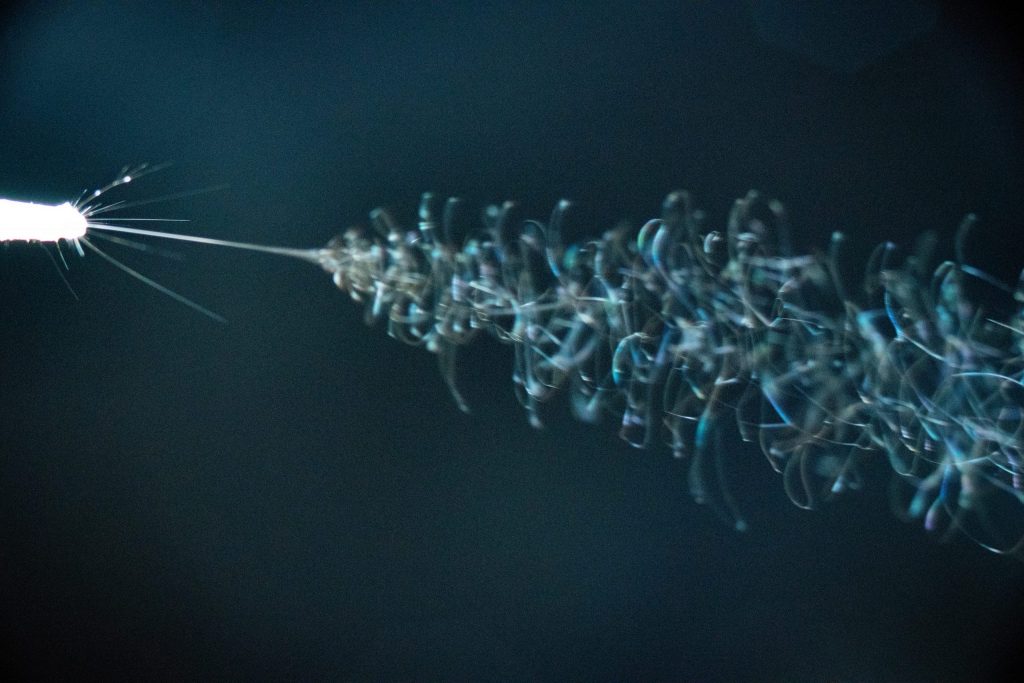

First proposed in the early 1900s to produce thinner artificial silk, electrospinning has been used for air filtration in cars, wound dressing and pharmaceutical drugs. Like spinning sugar, electrospinning involves using a liquidized material to create thin strands that eventually harden into the desired structure. Instead of heating the liquid, electrospinning applies a positive charge to it. The charge on the liquid creates an attraction between it and a neutral plate, placed some distance away. This attraction stretches the material towards the plate, creating a solid, fibrous material.

For accelerator targets, specialists turn metal or ceramic into a solid but porous material that consists of thousands of fiber strands less than a micrometer in diameter. That’s less than a hundredth the thickness of an average human hair, and about a third of a spider’s webbing.

When the particle beam collides with an electrospun target, the fibers won’t propagate any waves. The lack of potentially material-damaging waves means that these targets can withstand much higher beam intensity.

Instead of a pool, imagine you jump into a ball pit. Your collision will disrupt the arrangement of the balls immediately around you but leave the surrounding ones alone. The electrospun target acts the same way. The process leaves space between each fiber, allowing the fibers to expand uniformly, avoiding the jack hammer effect.

While this new technology potentially solves many of the issues with current targets, it has its own obstacles to overcome. Typically, the process to make an electrospun target takes days, with experts frequently having to stop to correct complications in the way the material accumulates.

Bidhar is developing and testing methods that increase the number of fiber spin-off points that form at a single time, produce a thicker nanofiber target, and decrease the amount of electricity needed to create the positive charge. These advancements would both speed up and simplify the process.

While he’s still trying different electrospinning techniques, Bidhar has already developed a new patent-pending electrospinning system, including a novel power supply.

Bidhar’s electrospinning unit is more compact, more lightweight, simpler and cheaper than most conventional units.

Its also much safer to use due to its limited output power. Present commercial power supplies put out an amount of electric power that far exceeds what is needed to make electrospun targets. Bidhar’s power supply unit reduces the electric power output and overall unit size by half, which also makes it safer to use.

In May 2018, Bidhar’s power supply won the TechConnect Innovation Award. Bidhar is encouraged by what this technology means for particle physics and also for other industries.

“Medical personnel would be able to use this power supply to create biodegradable wound dressings in remote and mobile locations, without a bulky and high-voltage unit,” Bidhar said.

Electrospun targets, like Bidhar’s power supply, could innovate the future of particle physics accelerators, allowing experiments such as DUNE to reach higher levels of beam intensity. These higher intensity beams will aid scientists in solving the enduring mysteries of astrophysics, nuclear physics and particle physics.

Learn more about electrospinning. This work is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.