neutrino

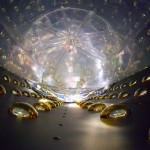

Deep in the dense core of a black hole, protons and electrons are squeezed together to form neutrons, sending ghostly particles called neutrinos streaming out. Matter falls inward. In the textbook case, matter rebounds and erupts, leaving a neutron star. But sometimes, the supernova fails, and there’s no explosion; instead, a black hole is born. Scientists hope to use neutrino experiments to watch a black hole form.

Finding a small discrepancy in measurements of the properties of neutrinos could show us how they fit into the bigger picture. One of those properties is a parameter called theta13. Theta13 relates deeply to how neutrinos mix together, and it’s here that scientists have seen the faintest hint of disagreement from different experiments.