Fermilab’s bison herd is genetically pure, displaying no evidence of cattle genes. Photo: Rashmi Shivni

Out in the crisp pastures north of Fermilab’s Main Ring, a herd of winter-coated fluff can be found huddling together and munching on hay in the nippy, January wind. The Fermilab bison – a spectacle for the community and an icon of the lab’s zeal for discovery – are a treasure with a lineage that dates back thousands of years.

However, as the American bison population rapidly declined during the early settlement era, bison were at risk of extinction, and farmers often bred them with other bovine species. So what is the backstory of Fermilab’s bison? Are they purebred, and where do they come from?

To answer these questions, Fermilab ecologist Ryan Campbell submitted tail hair samples of all 17 of the lab’s animals in October to Texas A&M University for genetic testing.

“We’ve had these wild bison for years,” Campbell said. “We’re just now finding out that they’re 100 percent bison with no evidence of cattle genes.”

Back in 1969 when Robert Wilson, the lab’s first director, first brought five bison to the laboratory, testing bison genetics was not a consideration.

When the Nature Conservancy reintroduced bison to their Nachusa Grasslands site in October 2014, they thought they had the first wild bison born east of the Mississippi River in over 200 years, according to Fermilab Roads and Grounds Manager Dave Shemanske.

“These groups genetically tested their animals before they brought them in, and we never did that in our 47-year history of receiving the animals,” Shemanske said. “We bought animals from reputable farms, inspected them prior to purchase, and we got kind of lucky with our herd.”

The DNA Technologies Core Laboratory at TAMU has mapped multiple bovid species genomes, and the Fermilab bison were tested against the national herds that the university previously sampled.

“This genomic testing technology is relatively new, and I don’t think we ever had a goal to have a ‘pure herd’ until we had scientific research to tell us about its importance,” Campbell said.

A pure herd is indeed valuable for a prairie ecosystem, as the animals are natural grazers and can tame tall grasses, which easily dominate prairies in the absence of wild bison. They also help create an environment where a variety of species – such as grasshopper sparrows, native butterflies, bees and reptiles – can thrive.

Fermilab’s bison are considered “wild” because of their genetic purity, Campbell said. Unlike other prairie preserves, Fermilab’s bison are kept on a pasture, not on Fermilab’s prairie land. This is to ensure their safety and the public’s safety when visiting.

Shemanske said all these factors are important for future purchases of wild bison.

“We need to test to make sure that any new bison bulls we bring every five to seven years don’t interrupt the genetics of our herd by accidentally introducing cattle genes into them,” he said.

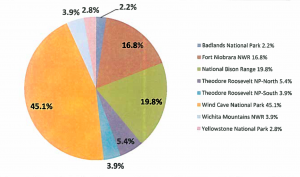

This chart shows the genomic contributions of eight core U.S. federal herds to the Fermilab bison samples submitted to Texas A&M University. Credit: James Derr, DNA Technologies Core Laboratory, Texas A&M University

The lab’s herd can lay claim not only to genetic purity, but also a lineage that spans the country. Eight federal bison herds throughout the United States are linked to the lab’s bison. Almost half of the genome in the herd sample came from Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, the same source population as the Nature Conservancy bison.

“There’s a lot of genetic diversity,” Campbell said.

Having pure bison genes from multiple, geographical areas can produce offspring that have an advantage against various diseases and that can withstand drastic changes in climate. Shemanske and Campbell plan to continue genetic testing before introducing new individuals, noting its usefulness in ensuring the herd’s diversity.

Armed with the knowledge that the herd is healthy and wholly bison, Campbell and Shemanske continue to promote the lab’s vision of cultivating an environment in which visitors can still watch and admire one of America’s great grazers.

“We have a world-class neutrino program here, but we also have a world-class environment,” Shemanske said. “The bison are an important piece of this community.”