The Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, an international collaboration hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, is preparing to build the most immense cryogenic particle detector the world has ever seen, and do it a mile underground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, South Dakota. The challenges are legion, among them, the sheer size and scope, worldwide coordination, logistics, and importantly, safety for both people and detector components.

“Our team has designed a large, integrated system and has been working closely with collaborators and vendors to deliver its components.”

Roza Doubnik, senior cryogenics engineer

This DUNE far detector is planned as a series of gigantic modules of varying designs that will be constructed sequentially over a period of a few years. The modules will consist of ultrasensitive detector components immersed in a bath of liquid argon, the first two of these each require about five Olympic swimming pools worth of the liquid, which at 1.4 times the density of water, comes to 17,000 metric tons each. International collaborators are planning to contribute two additional modules that would be slightly smaller, but the experiment is aiming for a final volume of liquid argon over 50,000 tons.

“The cryogenics system is a critical component of the project and must be highly reliable — it cannot serve as a testbed,” said Roza Doubnik, a senior cryogenics engineer at Fermilab working on the purification and regeneration systems for the DUNE cryogenics. “Our team has designed a large, integrated system and has been working closely with collaborators and vendors to deliver its components.”

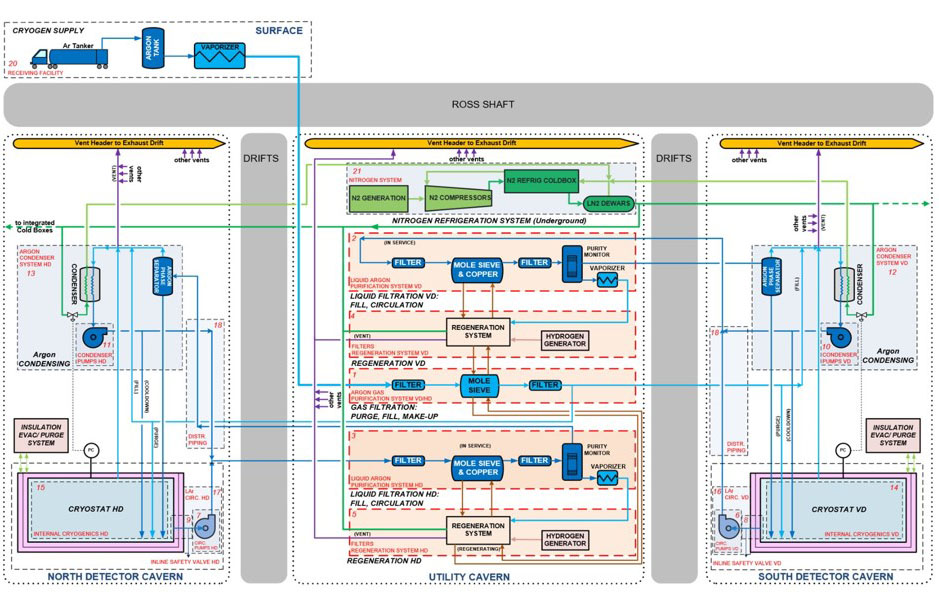

To fill the first cryostat, the DUNE cryogenics team has been preparing to receive about 1,000 truckloads of liquid argon over a period of about a year — on average four 20-ton truckloads per day, seven days a week. Keeping the argon cold enough to remain liquid for its mile-long descent to the detector spaces would be impractical, so when a truckload arrives the liquid will be vaporized at the surface before being piped underground where the industrial-scale cryogenics system will be in place.

Liquid argon, used in a variety of industrial, technical and scientific processes, is a transparent fluid that must be kept at minus 303 degrees Fahrenheit. Even though argon is plentiful and makes up about 1% of the air we breath, it doesn’t just fall out of the sky — it requires a distillation process of air at ultra-cold temperatures to separate it out from the oxygen and other gases. The DUNE cryogenics team has had to find liquid-argon vendors that can supply the prodigious amounts needed and organize delivery methods and schedules. Meanwhile, the team has determined all the processes and infrastructure required to get the argon into each of the highly insulated detector containers, called cryostats, and keep it liquefied and pure enough to run the experiment safely for 20 years.

Once underground, the argon gas will be piped first through a purification system, then into a readied cryostat to purge it of air. The purified gas will fill the cryostat from the bottom up, pushing the air out openings in the top. The team will repeat this process at least 10 times to reduce contamination levels in the volume to the parts-per-million level, filtering the argon each time. Once this is complete, the argon gas is passed through the liquefaction portion of the cryogenics system. Liquid nitrogen, with its boiling point being lower than that of argon, is used as the recondensing agent.

Due to the delicacy of its detector components, the second DUNE module requires a gradual cool-down before filling. For this process, sprayers at the top of the cryostat introduce atomized liquid argon droplets into the volume, and the mist distributes itself throughout the volume by means of gravity and convection. This continues until the volume is cooled to minus 298 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point filling begins.

Once a cryostat is filled, external pumps will continuously recirculate liquid argon through a purification system and the immersed detector begins taking data. Any bit of vaporized argon is recovered, recondensed, repurified and returned to the cryostat in the closed system.

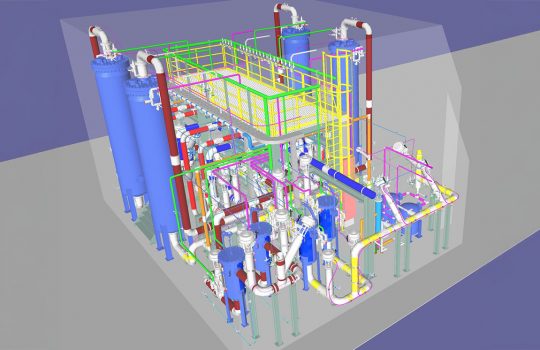

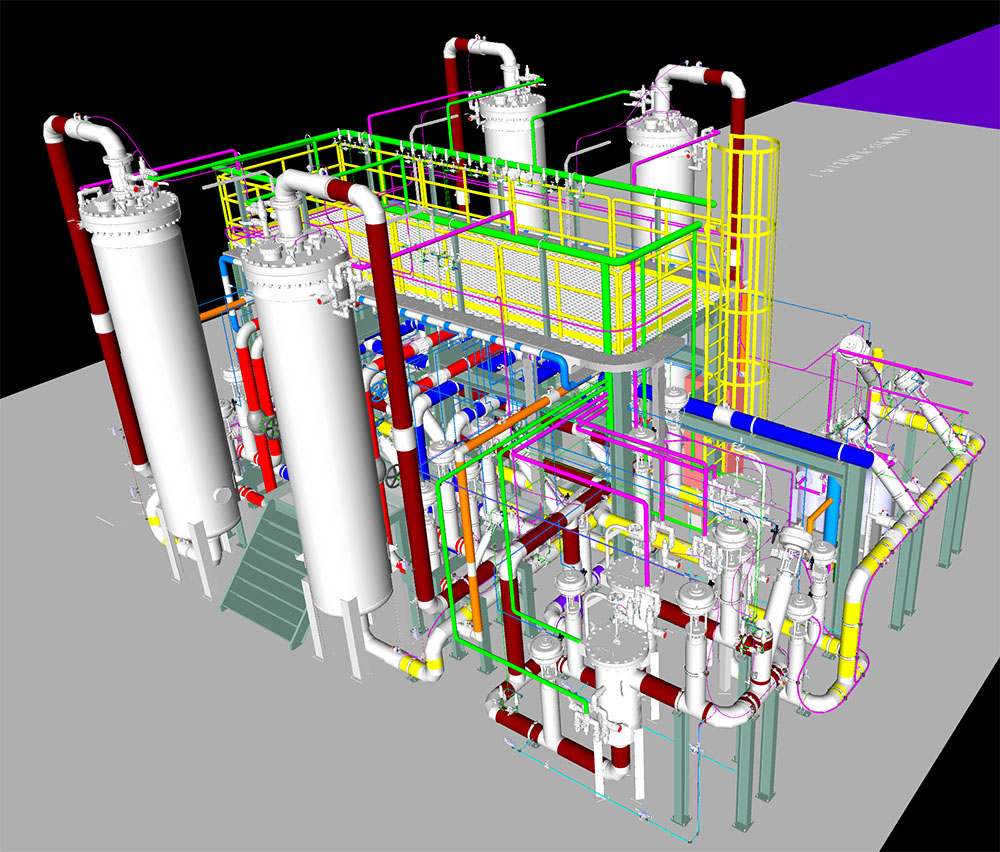

The cryogenics team’s design calls for integrable system components that are as standard as possible, that meet the performance requirements, and — importantly — that fit down the shaft that leads to the underground area. The team has already awarded contracts for the nitrogen system, liquid-argon pumps, and most of the process controls equipment, among other items, to vendors selected for their technical competence and experience. Other contracts are in the works, and some, including for the argon itself, are expected to be placed in the coming year or two, in time to have the deliveries start when the first detector module is fully installed.

For safety reasons, monitoring and managing the cryostat’s internal pressure and preventing leaks are of ultimate importance. Pressure safety valves will be placed on top of each cryostat, and valves to prevent leaks will be installed in side penetrations. In 2025, the team awarded a subcontract to procure these side safety valves. The selected vendor has provided the same valves for the DUNE prototype detectors at CERN and the SBND detector at Fermilab, all of which have operated successfully.

“The safety valves are crucial for guaranteeing safe and effective functioning of the cryogenic system.”

Zachery West, cryogenics engineer at Fermilab

“The safety valves are crucial for guaranteeing safe and effective functioning of the cryogenic system,” said Zachery West, cryogenics engineer at Fermilab. “This type of valve, open during normal operations, closes via a pneumatic actuator in case of emergency.”

Meanwhile, colleagues from CERN are in the process of procuring the argon condensers and related instrumentation, keeping up the team’s steady momentum towards completing the cryogenics system for the multi-module DUNE far detector, with safety always top of mind.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.