How do you contain over 15,000 tons of a liquid that must be kept at minus 303 degrees Fahrenheit for a science experiment? A science fiction author might send it up to outer space in a fancy tin can since it’s very cold there and everything is weightless. The Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, a nonfictional experiment with detectors that will be immersed in huge baths of cryogenic liquid argon, is going the opposite direction — down.

“By going underground, the DUNE detectors in South Dakota will significantly reduce cosmic backgrounds.”

Vincent Basque, Fermilab researcher

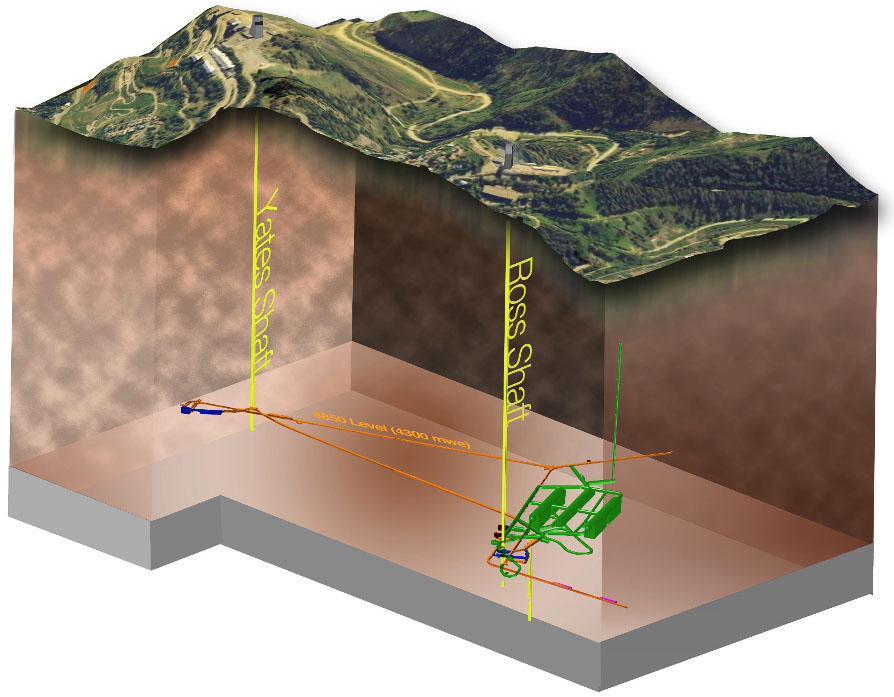

DUNE is the most sensitive experiment ever conceived for learning about the origins of the universe from the properties of neutrinos, among the first particles to be emitted by the Big Bang. The experiment needs to shield its particle detectors from the cosmic rays that constantly jet through space and bombard the Earth, lest they overwhelm and mask the relatively faint signals the experiment aims to capture. So DUNE researchers will build and run these detectors at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, South Dakota, underneath a mile of earth that will absorb most of the cosmic traffic.

“By going underground, the DUNE detectors in South Dakota will significantly reduce cosmic backgrounds,” said Fermilab postdoctoral researcher Vincent Basque. “This allows us to study neutrinos sent from the Fermilab beam in Illinois with high precision, detect neutrinos from astrophysical sources like the sun or a nearby supernova, and search for other extremely rare processes.”

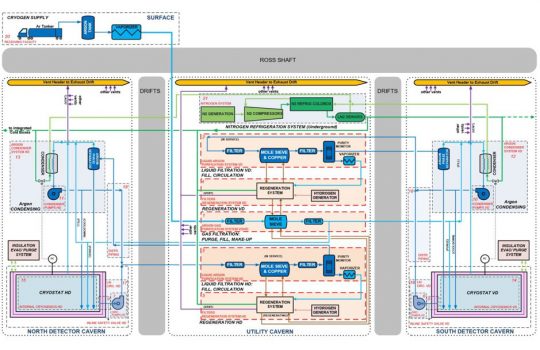

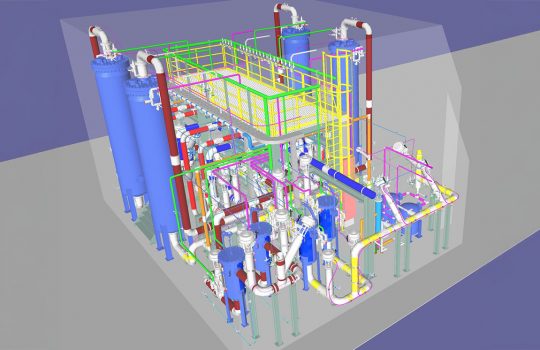

The DUNE collaboration — hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory — is currently preparing to install two of these multi-kiloton detector modules using variants of liquid-argon time projection chamber, or LArTPC, technology. International collaborators hope to contribute an additional two modules in coming years. Each module will be housed in an insulating container called a cryostat that is nearly 500,000 cubic feet in size — roughly the same volume as five Olympic-size swimming pools. Far from being available at your local hardware store, CERN has contracted with GTT, a company that designs cryostats for shipping liquefied natural gas, to design the cryostats. GTT has been designing smaller cryostats for CERN experiments since 2007. CERN, the largest European center for nuclear research that is collaborating on DUNE, is contributing the cryostats for the experiment.

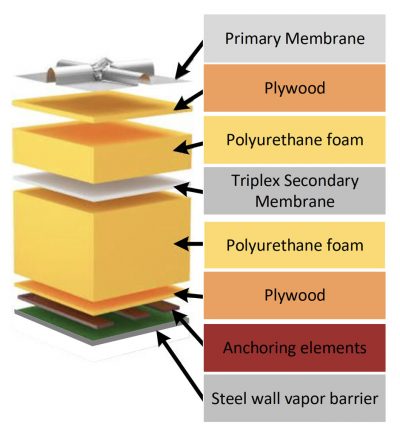

Cryostats for liquid-argon time projection chambers must be robust enough to resist the outward pressure of the fluid (1.4 times denser than water) and pliant enough to retain their integrity over a roughly 375 degrees Fahrenheit range between room and liquid argon temperatures. They must also be sufficiently insulated to maintain the cryogenic temperature level and able to accommodate an industrial-scale cryogenics system to maintain the required argon purity. Beyond that, CERN will construct the cryostats in place from pieces that fit down a 4-by-6-meter mine shaft.

“Making this possible has required detailed and precise design and logistics planning.”

Lluís Miralles Verge, CERN

“It’s the first time we will do something this big,” said Lluís Miralles Verge, the leader for the experiment’s cryostat project at CERN. “The DUNE LArTPCs will be installed in caverns that can only be reached via a deep shaft. Making this possible has required detailed and precise design and logistics planning.”

To achieve leakproof liquid and vapor containment, in addition to adequate insulation and support, the DUNE cryostats are composed of several layers. GTT’s tried-and-true design is of a style known as a membrane cryostat, because of the innermost layer that forms a membrane to contain the liquid cryogen. This layer, and all the others, come down the shaft in pieces and are assembled in the detector cavern, starting with the outer structure. Completion of the inner portions of a DUNE cryostat requires more than 5,000 individual pieces.

The primary and innermost layer is constructed of stainless steel, a material that doesn’t exude anything that could contaminate the argon. The corrugated sections are welded together to form the leakproof membrane that is in direct contact with the liquid argon.

Why the corrugations? They are important for mitigating the contraction effects in both dimensions on the metal as it cools to its final cryogenic temperature. Without them, the cryostat’s length would shrink by an impressive 20 inches or so, and burst the welds. Instead, each corrugation changes shape very slightly and the welds hold. Controlling the membrane contraction also, and importantly, helps keep the detector precisely in position.

“The DUNE prototypes at CERN have been invaluable,” said David Montanari, cryogenics project manager for DUNE. “They have demonstrated that the detector elements, cryostats and cryogenics work together properly, giving us confidence that the DUNE far detector cryostats will perform flawlessly.”

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.