“Happy birthday, Fermilab!”

Those well-wishes were recently offered from Secretary of Energy Rick Perry (beginning at 1:30), Congressman Bill Foster and Congressman Randy Hultgren on the occasion of Fermilab’s 50th anniversary.

Congress also recognized Fermilab’s 50th anniversary through two resolutions, in the House and the Senate.

Anniversary recognition came from our partner laboratory CERN as well, specifically from the CERN Staff Association.

Fermilab received many personal birthday cards from around the world. View them on our Facebook gallery.

And of course, Fermilab staff and users were enthusiastic about registering their birthday wishes by signing a giant birthday card on June 15, the anniversary date of day lab employees first came to work.

Thanks to our Washington, D.C., officials, to our friends and followers from around the world, and to our very own Fermilab staff and users for the birthday congratulations. May we enjoy another 50 years of science discovery.

Twenty-five years ago this month, Fermilab stood up its first website — one of the earliest websites in the United States.

The World Wide Web was born at CERN in Europe in 1989 as a tool for exchanging particle physics data. The first U.S. web server was created at Stanford Linear Accelerator Center in December 1991.

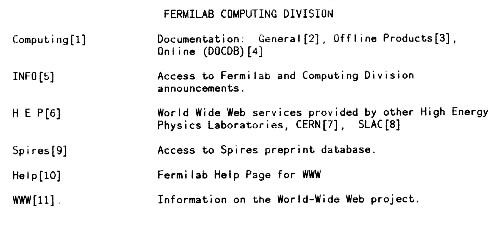

In June 1992, Fermilab’s Computing Division installed its first web server. In late 1992, Computing Division staff created Fermilab’s first HTML page.

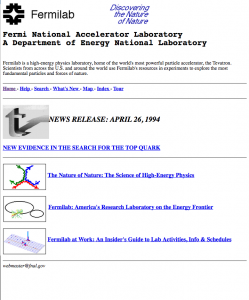

In 1992, the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois launched Mosaic, a graphical interface web browser that made the web navigable for people without computer expertise. In February 1994, Fermilab created the laboratory’s first pages designed for the public.

1994

In August 1996, the laboratory redesigned its growing volume of public webpages.

1996

A complete overhaul of the Fermilab website appeared on March 1, 2001, and its design and the technology behind its webpages has been updated several times since then:

2001

2004

2006

2009

2014

2017

Anna Grassellino of Fermilab and James Sauls of Northwestern University are co-directors of the newly launched Center for Applied Physics and Superconducting Technologies. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Northwestern University and the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have established a new collaboration that will enhance the world-class discovery that is a hallmark of each institution.

The Center for Applied Physics and Superconducting Technologies (CAPST) formally recognizes a broad intersection of scientific pursuits and complementary state-of-the-art facilities. CAPST lays the groundwork for the cross-utilization of technical expertise, facilities, and equipment and establishes a partnership that will foster joint scientific research, mentorship, and new opportunities for researchers, graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows.

Research at the center will include a focus on advancing superconductivity, which is expected to produce societal gains in the fields of particle physics, solid-state physics, materials science, medicine, energy and environmental sciences.

Superconductors are materials that conduct electricity with no resistance, and superconducting magnets — like those used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and particle accelerators — must be cooled to cryogenic temperatures during operation. In its superconducting state, these devices can conduct much larger electric currents than any ordinary wire, creating intense magnetic fields.

The breadth of research at CAPST will further investigations into the upper limit of performance of superconductors for next-generation particle accelerators, help develop superconducting devices for quantum information science and technology and expand the frontier in superconducting materials.

“Northwestern and Fermilab share a commitment to foundational discovery that can lead to transformative advances in many arenas,” said Northwestern Vice President for Research Jay Walsh. “By combining our efforts in this way, we create an ‘ecosystem’ that provides the tools and collaborative environment to enable great scientists to pursue high-impact research. What is especially promising about this partnership is that each of our institutions brings unique strengths that allow us to meld theory and practice in exciting ways.”

Walsh’s colleagues at Fermilab agree, expressing enthusiasm about the prospects of the partnership.

“At Fermilab we have unique facilities, an expansive infrastructure and experience built over decades,” said Sergey Belomestnykh, Fermilab chief technology officer. “Recent breakthroughs at Fermilab in improving performance of superconducting radio-frequency cavities for accelerators opened new directions for research in this field. We were seeking collaboration with experts in superconductivity and found a good match at Northwestern University, with its teams of world-leading experts in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and the Department of Materials Science and Engineering. Their insights into behavior of superconductors will help to uncover performance potentials of traditional and new materials in particle accelerators and perhaps quantum computing.”

Fermilab is a world leader in the field of accelerator science and technology research, in particular for radio-frequency superconductivity and high-field superconducting magnets. These technologies enable large- and small-scale accelerators with applications ranging from particle physics to solid-state physics, including materials science, biology, medicine, energy and the environment.

“The center is a marriage of basic science, applied research and technology development,” said CAPST co-director James Sauls, physics and astronomy, and an expert in theoretical physics. “This effort provides cross-institutional access to high-value research equipment and facilities while also allowing Fermilab to tap into Northwestern’s expertise in the field of superconductivity and materials physics. An immediate goal is to develop a fundamental understanding of the physics that sets the ultimate limit to the performance of superconducting radio-frequency (SRF) cavities for particle acceleration.”

The collaboration is already paying dividends, with Northwestern having been awarded a research grant for CAPST from the Physics Division of the National Science Foundation (NSF).

“This new award will allow the CAPST research team to develop a detailed understanding for the physical processes that limit the accelerating field and quality factor of SRF cavities and with that knowledge to push the performance level toward theoretical limits,” Sauls said. “The grant from NSF will also help bring a greater presence of accelerator science to the university and provide new research opportunities for graduate students, both at Northwestern and Fermilab.”

A large variety of SRF cavities are used in particle accelerators. Fermilab produced its first high-energy particle beam on March 1, 1972. Since then hundreds of experiments have used Fermilab’s accelerators to study matter at ever-smaller length scales and investigate physical processes thought to take place in the early evolution of the universe.

Anna Grassellino, CAPST co-director and a Fermilab physicist, is working to develop SRF cavities with improved performance at lower operational costs. Her research on nitrogen doping of niobium SRF cavities was a breakthrough discovery that led to a major improvement in the performance (quality factor) of SRF cavities. The Fermilab results have been adopted as the standard for SRF cavities for particle accelerators used in other research and industrial laboratories worldwide. The research is expected to enhance superconducting accelerators used for a broad spectrum of scientific machines, medical devices and nuclear energy applications.

“It is fascinating how particle accelerators can be very large and complex installations, but their ultimate performance depend strongly on the physics of superconducting materials at the nanometer scale,” Grassellino said. “At Fermilab, we have found that to push the boundaries of accelerator technology, we must confront the science and fundamental understanding of the physics in play in the superconducting materials used for cavities or for magnets. Fermilab knowledge and experience in the applied world, together with the knowledge and understanding of superconductivity from the Northwestern side, is a very powerful mix. And I can’t wait for this mix to guide us to the next breakthrough in accelerator technology.”

Northwestern faculty Venkat Chandrasekhar, William Halperin, John Ketterson, Jens Koch and Nate Stern, all physics and astronomy, as well as David Seidman, materials science, will lead various research efforts within the center. Eight Fermilab staff members, including Anna Grassellino and Alexander Romanenko, who hold adjunct appointments in physics and astronomy at the university, are part of CAPST.

Alex Romanenko leads Fermilab’s quantum computing architecture effort based on superconducting radio-frequency cavities, like those seen here. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Members from each institution meet in person at Fermilab and Northwestern about twice per month, also using SMART electronic whiteboards and video communication to share information digitally.

In addition to SRF accelerators, the center will foster research and collaboration in the rapidly developing research field of quantum computing.

Romanenko is leading the new SRF-based quantum computing architecture effort at Fermilab, and a new subkelvin dilution refrigerator will be installed in the fall to begin experiments.

Koch, director of graduate studies in Northwestern’s Graduate Program in Applied Physics, is an expert in quantum electronics and superconducting quantum circuits (SQC). Quantum computing based on SQCs takes advantage of the preservation of information provided by superconducting circuit elements. There are major efforts under way at universities, places like Google, Microsoft, IBM and Northrop-Grumman, and national laboratories to develop the next generation of computing machines based on quantum logic elements. CAPST will pursue superconducting based quantum circuits.

“Jens Koch is a leading expert in the theory of superconducting quantum circuits and has played an important role in discovering how to improve the performance of superconducting quantum bits (qubits), the basic element of a quantum computer,” Sauls said. “Fermilab and Northwestern already have basic research programs aimed at quantum computing. The combination of our efforts will allow us to pursue new directions with the goal of developing new types of qubits for next generation superconducting quantum devices.”

Fermilab, Argonne Lab and the University of Chicago are to collaborate on advancing the science and engineering of quantum information. Image courtesy of Nicholas Brawand

The University of Chicago is collaborating with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory to launch an intellectual hub for advancing academic, industrial and governmental efforts in the science and engineering of quantum information.

This hub within the Institute for Molecular Engineering (IME), called the Chicago Quantum Exchange, will facilitate the exploration of quantum information and the development of new applications with the potential to dramatically improve technology for communication, computing and sensing. The collaboration will include scientists and engineers from the two national labs and IME, as well as scholars from UChicago’s departments of physics, chemistry, computer science and astronomy and astrophysics.

Quantum mechanics governs the behavior of matter at the atomic and subatomic levels in exotic and unfamiliar ways compared to the classical physics used to understand the movements of everyday objects. The engineering of quantum phenomena could lead to new classes of devices and computing capabilities, permitting novel approaches to solving problems that cannot be addressed using existing technology.

“The combination of the University of Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, working together as the Chicago Quantum Exchange, is unique in the domain of quantum information science,” said Matthew Tirrell, dean and Founding Pritzker Director of the Institute for Molecular Engineering and Argonne’s deputy laboratory director for science. “The CQE’s capabilities will span the range of quantum information, from basic solid state experimental and theoretical physics, to device design and fabrication, to algorithm and software development. CQE aims to integrate and exploit these capabilities to create a quantum information technology ecosystem.”

Serving as director of the Chicago Quantum Exchange will be David Awschalom, UChicago’s Liew Family Professor in Molecular Engineering and an Argonne senior scientist. Discussions about establishing a trailblazing quantum engineering initiative began soon after Awschalom joined the UChicago faculty in 2013 when he proposed this concept, subsequently developed through the recruitment of faculty and the creation of state-of-the-art measurement laboratories.

Fermilab physicist Aaron Chou is one of the lead scientists in a Fermilab-UChicago project to look for dark matter particles using quantum sensors. Photo: Reidar Hahn

“We are at a remarkable moment in science and engineering, where a stream of scientific discoveries are yielding new ways to create, control, and communicate between quantum states of matter,” Awschalom said. “Efforts in Chicago and around the world are leading to the development of fundamentally new technologies, where information is manipulated at the atomic scale and governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. Transformative technologies are likely to emerge with far-reaching applications, ranging from ultra-sensitive sensors for biomedical imaging to secure communication networks to new paradigms for computation. In addition, they are making us re-think the meaning of information itself.”

The collaboration will benefit from UChicago’s Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, which supports the creation of innovative businesses connected to UChicago and Chicago’s South Side. The CQE will have a strong connection with a major Hyde Park innovation project that was announced recently as the second phase of the Harper Court development on the north side of 53rd Street, and will include an expansion of Polsky Center activities. This project will enable the transition from laboratory discoveries to societal applications through industrial collaborations and startup initiatives.

Companies large and small are positioning themselves to make a far-reaching impact with this new quantum technology. Alumni of IME’s quantum engineering Ph.D. program have been recruited to work for many of these companies. The creation of CQE will allow for new linkages and collaborations with industry, governmental agencies and other academic institutions, as well as support from the Polsky Center for new start-up ventures.

This new quantum ecosystem will provide a collaborative environment for researchers to invent technologies in which all the components of information processing — sensing, computation, storage, and communication – are kept in the quantum world, Awschalom said. This contrasts with today’s mainstream computer systems, which frequently transform electronic signals from laptop computers into light for internet transmission via fiber optics, transforming them back into electronic signals when they arrive at their target computers, finally to become stored as magnetic data on hard drives.

IME’s quantum engineering program is already training a new workforce of “quantum engineers” to meet the need of industry, government laboratories, and universities. The program now consists of eight faculty members and more than 100 postdoctoral scientists and doctoral students. Approximately 20 faculty members from UChicago’s Physical Sciences Division also pursue quantum research. These include David Schuster, assistant professor in physics, who collaborates with Argonne and Fermilab researchers.

Combining strengths in quantum information

Alex Romanenko leads Fermilab’s quantum computing architecture effort based on superconducting radio-frequency cavities, like those seen here. Photo: Reidar Hahn

The collaboration will rely on the distinctive strengths of the University and the two national laboratories, both of which are located in the Chicago suburbs and have longstanding affiliations with the University of Chicago.

Fermilab’s interest in quantum computing stems from the enhanced capabilities that the technology could offer within 15 years, said Joseph Lykken, Fermilab deputy director and senior scientist.

“The Large Hadron Collider Experiments, ATLAS and CMS, will still be running 15 years from now,” Lykken said. “Our neutrino experiment, DUNE, will still be running 15 years from now. Computing is integral to particle physics discoveries, so advances that are 15 years away in high-energy physics are developments that we have to start thinking about right now.”

Lykken noted that almost any quantum computing technology is by definition a device with atomic-level sensitivity that potentially could be applied to sensitive particle physics experiments. An ongoing Fermilab-UChicago collaboration is exploring the use of quantum computing for axion detection. Axions are candidate particles for dark matter, an invisible mass of unknown composition that accounts for 85 percent of the mass of the universe.

Another collaboration with UChicago involves developing quantum computer technology that uses photons in superconducting radio frequency (SRF) cavities for data storage and error correction. These photons are light particles emitted as microwaves. Scientists expect the control and measurement of microwave photons to become important components of quantum computers.

“We build the best superconducting microwave cavities in the world, but we build them for accelerators,” Lykken said. Fermilab is collaborating with UChicago to adapt the technology for quantum applications.

Fermilab also has partnered with the California Institute of Technology and AT&T to develop a prototype quantum information network at the lab. Fermilab, Caltech and AT&T have long collaborated to efficiently transmit the Large Hadron Collider’s massive data sets. The project, a quantum Internet demonstration of sorts, is called INQNET (INtelligent Quantum NEtworks and Technologies).

The Fermilab-UChicago collaboration to look for fundamental particles called axions uses a quantum sensor, shown here next to a penny for scale. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Fermilab also is working to increase the scale of today’s quantum computers. Fermilab can contribute to this effort because quantum computers are complicated, sensitive, cryogenic devices. The laboratory has decades of experience in scaling up such devices for high-energy physics applications.

“It’s one of the main things that we do,” Lykken said.

At Argonne, approximately 20 researchers either conduct quantum-related research or express interest in joining the field. Many of them have joint appointments at the laboratory and UChicago. Fermilab has about 25 scientists and technicians working on quantum research initiatives related to the development of particle sensors, quantum computing, and quantum algorithms.

“This is a great time to invest in quantum materials and quantum information systems,” said Supratik Guha, director of Argonne’s Nanoscience and Technology Division and a professor of molecular engineering at UChicago. “We have extensive state-of-the-art capabilities in this area.”

Argonne proposed the first recognizable theoretical framework for a quantum computer, work conducted in the early 1980s by Paul Benioff. Today, including joint appointees, Argonne’s expertise spans the spectrum of quantum sensing, quantum computing, classical computing and materials science.

Argonne and UChicago already have invested approximately $6 million to build comprehensive materials synthesis facilities — called “The Quantum Factory” — at both locations. Guha, for example, has installed state-of-the-art deposition systems that he uses to layer atoms of materials needed for building quantum structures.

“Together we will have comprehensive capabilities to be able to grow and synthesize one-, two- and three-dimensional quantum structures for the future,” Guha said. These structures, called quantum bits — qubits — serve as the building blocks for quantum computing and quantum sensing.

Argonne also has theorists who can help identify problems in physics and chemistry that could be solved via quantum computing. Argonne’s experts in algorithms, operating systems, and systems software, led by Rick Stevens, associate laboratory director and UChicago professor in computer science, will play a critical role as well, because no quantum computer will be able to operate without connecting to a classical computer.

Fermilab is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. A U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, Fermilab is located near Chicago, Illinois, and operated under contract by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on Twitter at @Fermilab.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation’s first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America’s scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.