Inverse, Dec. 4, 2015: Scientists at Fermilab tell us that an experiment designed to test the so-called “holographic principle” found no evidence that the universe is an illusory 3D projection of information encoded at the distant edges of the universe.

Astronomy Magazine, Dec. 10, 2015: This past year, a sky survey uncovered nine dwarf galaxies within 1 million light-years of the Milky Way. And one of the galaxies from this Dark Energy Survey (DES) was a prime dark matter target: Reticulum II.

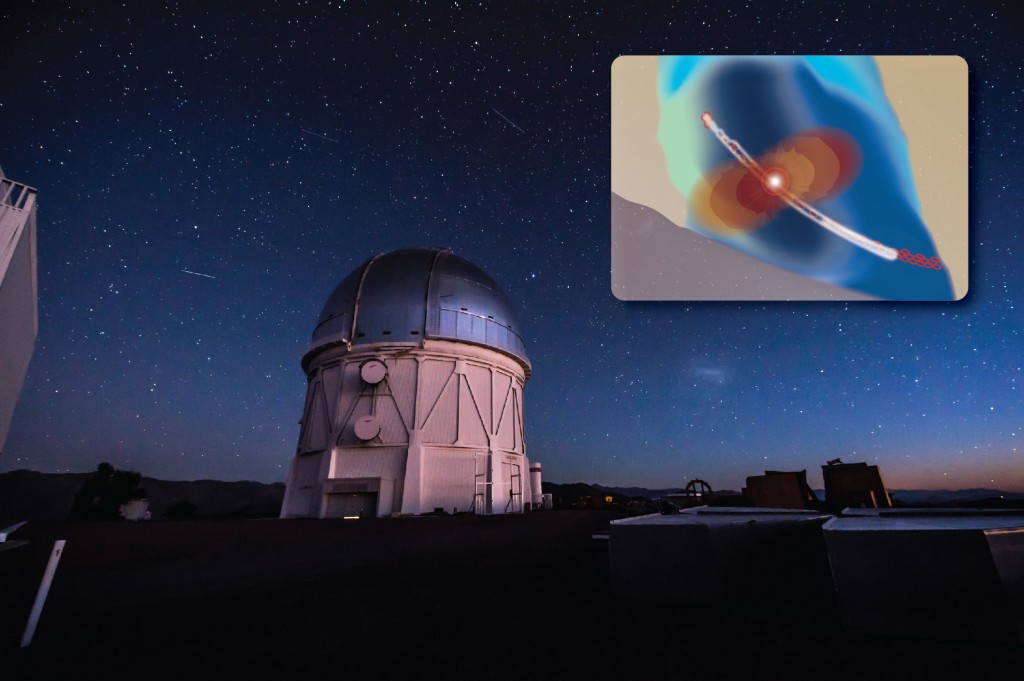

The Dark Energy Camera, built to map the southern sky, sits inside a telescope in Chile. As its name suggests, it helps scientists to look for the origin of dark energy, the mysterious force that pushes the universe apart.

Now the camera has another job: It’s acting as eyes in the hunt for sources of gravitational waves.

A massive object, such as a star or a black hole, distorts the fabric of space — sort of the way a bowling ball bends the surface of a trampoline. If the object is accelerating, this distortion pulses outward in ripples traveling at the speed of light. These ripples are gravitational waves. But nobody has been able to record them so far.

“Gravitational waves are sort of the last prediction of Einstein’s that has yet to be experimentally verified,” said Rick Kessler, senior research associate at the University of Chicago.

Theory predicts that even puny humans make gravitational waves. But because our mass and accelerations are small, they’re too weak to notice. Most gravitational waves are. That’s why scientists haven’t directly detected them yet, although Albert Einstein predicted their existence 100 years ago.

There is indirect evidence that gravitational waves exist. It comes from a particular system of two neutron stars orbiting each other about 20,000 light-years away from Earth. Scientists have monitored the dizzying dance of these compact stars, together known as the Hulse-Taylor system, for more than 40 years.

Einstein predicted that gravitational waves carry energy away from a system. Removing energy from two orbiting objects shrinks their paths as if they were being lassoed together. The objects get closer and closer until, eventually, they merge in a cataclysmic collision.

Watching the stars in the Hulse-Taylor system gradually fall toward each other gives scientists indirect evidence that Einstein was right (again) — these neutron stars are losing energy in the form of gravitational waves, exactly as predicted.

“But we’re experimentalists,” Kessler said. “We want direct evidence.”

That’s where the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory comes in. Scientists built LIGO in an attempt to detect gravitational waves for the first time. And to find out more about the sources of potential gravitational waves, LIGO scientists are now coordinating their measurements with observations made by the Dark Energy Camera on the Blanco Telescope.

DES-GW is using the Dark Energy Camera in the Blanco Telescope in Chile to look for sources of gravitational waves. The red, orange and yellow areas the inset represent gravitational waves, and the bright light represents the source of these waves. The thin white arc illustrates a narrow area of sky where LIGO scientists believe a gravitational wave may have originated. Photo: Reidar Hahn; graphic: Diana Brandonisio

LIGO, funded by the National Science Foundation and other public and private institutions, has two detectors. One resides in Louisiana, the other in the state of Washington. They’re L-shaped, each outfitted with two perpendicular arms 2.5 miles long. Lasers shoot through the arms and bounce off mirrors that send them back to their source to combine and form what are known as interference patterns. Observing changes to these interference patterns due changes in space-time is key to directly detecting gravitational waves. That’s because gravitational waves ever so slightly squeeze and then stretch space, drawing separated points of matter a smidge closer together and then a smidge further apart.

The strongest space-time ripples are produced by violent cosmic events like the merging of two neutron stars (which will happen to the Hulse-Taylor system in 300 million years) or the collision of two black holes. Although these waves are actually quite feeble by the time they travel a few hundred million light-years to Earth, they will almost imperceptibly squeeze and stretch LIGO’s detector arms.

This faint manipulation will temporarily shorten or lengthen the detectors’ arms by 1,000 times less than the size of a proton. Changing the arm length alters the distance the lasers travel, which will show up as a slight shift in their interference pattern. Scientists can then read the interference pattern like a gravitational wave’s fingerprint, giving them direct evidence that space-time ripples exist.

“The detectors will tell us that a gravitational wave came from somewhere in a banana-shaped band of sky,” said Daniel Holz, associate professor at the University of Chicago who is on the LIGO experiment. “The problem is that the band is very large. It’s on the order of 400 times the size of the full moon.”

Although LIGO can point scientists in the general direction from which gravitational wave came, it can’t pick out the exact location of the source.

“That’s why they need the eyes of the Dark Energy Camera to go look in that general direction,” said Marcelle Soares-Santos, associate scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab.

Members of the Dark Energy Survey, including Soares-Santos and other Fermilab scientists, have partnered with LIGO in the hunt for gravitational waves. They’re calling themselves the DES-GW group. Holz, who is also a member of DES-GW, said the team is a mixture of both gravitational wave and dark energy survey experts.

DES-GW will use the Dark Energy Camera to help LIGO search for the source of the gravitational waves it detects. Unlike most telescopes, the Dark Energy Camera is just the right size and has the right sensitivity to act as LIGO’s eyes. It can cover the banana-shaped area of the sky that LIGO looks at in 20 to 30 images.

When LIGO thinks it’s detected a gravitational wave, it will alert DES-GW collaborators, who will alert the Dark Energy Camera operators. LIGO and DES-GW have already joined forces and begun working together during the current season.

“With the Dark Energy Camera we’re trying to find an optical signature that accompanies the gravitational waves,” said Kessler, who is also a member of DES-GW.

“This is the frontier of science — we don’t really know what we’ll see,” Holz said. “But there’s an expectation that some systems will emit light at the same time as gravitational waves.”

Using the Dark Energy Camera to see this light, the optical signature of the gravitational waves’ source, could tell scientists more about the systems that produce them. This system may be made up of two neutron stars, two black holes or a neutron-black hole pair. And it would make history.

“We would be the first ones to directly detect gravitational waves and see light from the same event,” Soares-Santos said.

Soares-Santos is most excited about the potential of using this light as a tool to reconstruct the history of expansion of the universe, the same way supernovae are used today.

“There are lots of ifs and maybes,” Soares-Santos said of this possibility. “But at the same time, it’s exciting.”

Holz finds the most thrill in the prospect of surprise.

“Since we’ve never measured the universe in this way before, we just don’t know what’s out there,” Holz said. “That’s the real excitement.”

Pranav Sivakumar, a student at the Illinois Math and Science Academy, was recently recognized by President Barack Obama at White House Astronomy Night. Fermilab Ask-a-Scientist and Saturday Morning Physics talks were significant influences in his decision to pursue science. Photo: Reidar Hahn

Pranav Sivakumar, a junior at the Illinois Math and Science Academy, began attending Fermilab public lectures with his parents when he was in the fourth grade.

At first, as one might expect of an elementary school student, Sivakumar didn’t exactly know what was going on at Saturday Morning Physics and Ask-a-Scientist. But the scientists’ enthusiasm enthralled him.

“They really put in a lot of effort, going out of their way to teach. I caught some of that energy, and it’s stuck with me,” said Sivakumar, who is now 15 years old. “Fermilab has motivated me and focused me in the direction I wanted to go.”

This direction turned out to be astrophysics, specifically the study of gravitationally lensed quasars. Quasars are bright objects around black holes. When viewed from Earth, the light from gravitationally lensed quasars bends around a massive galaxy in front of them. This effect makes one quasar appear to be two or more quasars.

“Talking to Fermilab scientists, I realized how important gravitationally lensed quasars were in understanding dark matter and dark energy. This made me want to work with them,” Sivakumar said. Lensed quasars tell scientists about the rate of expansion of the universe, which can provide clues about enigmatic dark matter and dark energy.

For the Google Science Fair, a worldwide online science and technology competition among teens, Sivakumar developed algorithms to identify gravitationally lensed quasar candidates from data taken by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The algorithms help determine if two or more images of light are from a single lensed quasar or multiple quasars. With this project, he won the Virgin Galactic Pioneer Award and was one of 20 global finalists.

While working on this project, Sivakumar said he found mentors in two Fermilab scientists, Brian Nord and Chris Stoughton.

“The logic that he used to set up his algorithm is competitive with something that we would do,” said Nord, a research associate. “And he found a lensed quasar that was detected independently by our colleagues. The work that he’s done is something that requires persistence, focus and hard work.”

Soon after being recognized by the Google Science Fair, Sivakumar got a shout-out from President Obama in a speech at the White House Astronomy Night in October. Obama also mentioned how Fermilab’s public programs inspired Sivakumar’s work.

Sivakumar still looks to Fermilab scientists for inspiration and illumination. He recently visited the lab to continue working on an extension of his Google Science Fair quasar project with Fermilab astrophysicists, including Nord.

“We have a plan to work more with Pranav and see how far we can carry these algorithms,” Nord said.

“It’s all been fantastic,” Sivakumar said. “For the future, I want to continue in astrophysics. I’m really enjoying the way things are going.”

And when the President publicly praises you, who wouldn’t?

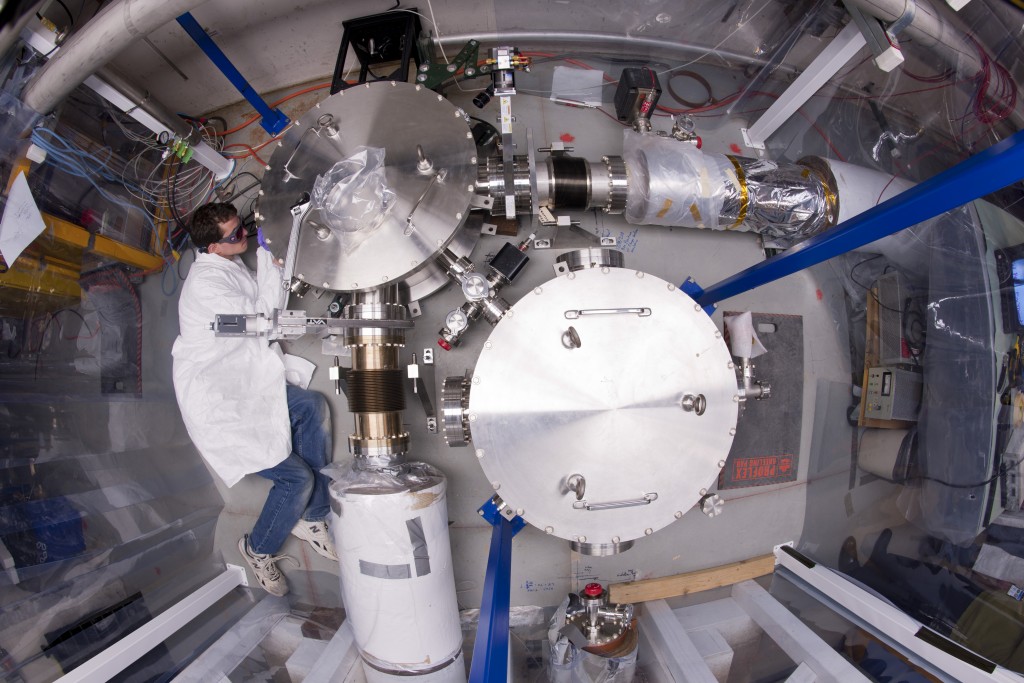

A member of the Holometer collaboration works on the sensitive space-time measuring device, located at Fermilab in Illinois. Photo: Fermilab

The extremely sensitive quantum-spacetime-measuring tool will serve as a template for scientific exploration in the years to come.

There has never been anything like the Holometer.

Based at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab in Illinois, the Holometer isn’t much to look at. It’s a small array of lasers and mirrors with a trailer for a control room. But the low-tech look of the device belies the fact that it is an unprecedentedly sensitive instrument, able to measure movements that last only a millionth of a second and distances that are a billionth of a billionth of a meter – a thousand times smaller than a single proton.

Our common sense, and the laws of physics, assumes that space and time are continuous. The Holometer challenges this assumption. We know that energy on the atomic level, for instance, is not continuous and comes in small, indivisible amounts. The Holometer was built to test if space and time behave the same way.

If they do, this would mean that everything is pixelated, like a digital image. When you zoom in far enough, you see that a digital image is not smooth, but made up of individual pixels. An image can only store as much data as the number of pixels allows. If the universe is similarly segmented, and hence more blurry than we think, then there would be a limit to the amount of information space-time can contain.

The main theory the Holometer was built to test was posited by Craig Hogan, a professor of astronomy and physics at the University of Chicago and the head of Fermilab’s Center for Particle Astrophysics. In a new result released this week after a year of data-taking, the Holometer collaboration has announced that it has ruled out Hogan’s theory of a pixelated universe to a high level of statistical significance. This means the Holometer did not detect the amount of correlated holographic noise – quantum jitter – that this particular model of space-time predicts.

But as Hogan emphasizes, that’s just one theory, and with the Holometer, this team of scientists has proven that space-time can be probed at an unprecedented level.

“This is just the beginning of the story,” Hogan said. “We’ve developed a new way of studying space and time that we didn’t have before. We weren’t even sure we could attain the sensitivity we did.”

The Holometer is a deceptively simple device. It uses a pair of laser interferometers placed close to one another, each sending a one-kilowatt beam of light through a beam splitter and down two perpendicular arms, 40 meters each. The light is then reflected back into the beam splitter where the two beams recombine. If no motion has occurred, then the recombined beam will be the same as the original beam. But if fluctuations in brightness are observed, researchers will then analyze these fluctuations to see if the splitter is moving in a certain way, being carried along on a jitter of space itself.

According to Fermilab’s Aaron Chou, project manager of the Holometer experiment, the collaboration looked to the work done to design other, similar instruments, such as the one used in the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) experiment. Chou said that once the Holometer team realized that this technology could be used to study the quantum fluctuation they were after, the work of other collaborations using laser interferometers (including LIGO) was invaluable.

“No one has ever applied this technology in this way before,” Chou said. “A small team, mostly students, built an instrument nearly as sensitive as LIGO’s to look for something completely different.”

The challenge for researchers using the Holometer is to eliminate all other sources of movement until they are left with a fluctuation they cannot explain. According to Fermilab’s Chris Stoughton, scientist on the Holometer experiment, the process of taking data was one of constantly adjusting the machine to remove more noise.

“You would run the machine for a while, take data, and then try to get rid of all the fluctuation you could see before running it again,” he said. “The origin of the phenomenon we’re looking for is a billion billion times smaller than a proton, and the Holometer is extremely sensitive, so it picks up a lot of outside sources, such as wind and traffic.”

If the Holometer were to see holographic noise that researchers could not eliminate, it might be detecting noise that is intrinsic to space-time, which may mean that information in our universe could actually be encoded in tiny packets in two dimensions.

The fact that the Holometer ruled out his theory to a high level of significance proves that it can probe time and space at previously unimagined scales, Hogan said. It also proves that if this quantum jitter exists, it is either much smaller than the Holometer can detect, or is moving in directions the current instrument is not configured to observe.

So what’s next? Hogan said the Holometer team will continue to take and analyze data, and will publish more general and more sensitive studies of holographic noise. The collaboration already released a result related to the study of gravitational waves.

And Hogan is already putting forth a new model of holographic structure that would require similar instruments of the same sensitivity, but different configurations sensitive to the rotation of space. The Holometer, he said, will serve as a template for an entirely new field of experimental science.

“It’s new technology, and the Holometer is just the first example of a new way of studying exotic correlations,” Hogan said. “It is just the first glimpse through a newly invented microscope.”

The Holometer experiment is supported by funding from the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. The Holometer collaboration includes scientists from Fermilab, the University of Chicago, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Michigan.

- Aaron Chou, project manager of the Holometer, and grad student Brittany Kamai work on the laser beam that powers the Holometer. Photo: Fermilab

- A scientist works on the laser interferometer at the heart of the Holometer experiment. Photo: Fermilab